Listening for Schubert’s “Doppelgängers”

David Løberg Code

KEYWORDS: Schubert, doppelganger, Heine, song, analysis, key characteristics

ABSTRACT: A doppelgänger is the ghostly double or wraith of a living person. This essay adopts and adapts this legend to an analysis of Franz Schubert’s song “Der Doppelgänger.” I begin by discussing ways in which the myth of the doppelgänger might relate to Schubert’s personality and other extramusical features such as affective key characteristics. Next, these constructions are mapped onto the piece itself, exploring multiple implications of motivic pitch structures and binary oppositions among chords and modalities. After tracing these features through the piece, I relate this detailed analysis to an interpretation of the text, and finally, aspects of Schubert’s personal life.

Copyright © 1995 Society for Music Theory

[1] “Still ist die Nacht” is the opening line of an untitled poem in Heinrich Heine’s collection, Die Heimkehr. Most of us know this poem by its inclusion in Franz Schubert’s Schwanengesang.(1) Regarding Schubert’s setting of the poem, Jack Stein describes it as “painfully wrong in its interpretation of the poem.” For example, “the first stanza, which Schubert sets in a darkly atmospheric, highly charged recitative over somber chords

[2] Schubert’s invocation of “Der Doppelgänger” brings to the foreground a host of cultural myths and imagery that would otherwise be absent from the opening of Heine’s poem. Literally meaning the ‘double-goer,’ the idea of a “spirit double, an exact but usually invisible replica of every human, bird, or beast is an ancient one” (Encyclopaedia Britannica 1985, 182). In Schubert’s time, the character of the doppelgänger was probably best known through the literary works of Johann Wolfgang Goethe and E.T.A. Hoffmann. That Schubert was familiar with the myth is evident, not only due to his choice of title, but even because of his spelling of the word. In the original poem, Heine uses the word “doppeltgänger,” (doubled-goer) while Schubert (omitting the “t”) chose the more common form of the word. Furthermore, Given that Heine uses the word only once in the last stanza of the poem, he apparently wished to postpone or perhaps even downplay the mythical associations. In rebutting what he calls Stein’s “often maddeningly wrongheaded study of Schubert’s Heine songs,” Richard Kramer (1985, 219) argues that it is entirely appropriate for Schubert to remake Heine’s poem. “It is in the nature of Romantic art,” says Kramer, “that idiosyncratic, personal style is a deep part of the message.

[3] Schubert may have identified with the notion of the doppelgänger—a shadow-self—because of the double life he himself apparently led. As his friend Eduard Bauernfeld described him, “Schubert had, so to speak, a double nature.

[4] “Der Doppelgänger” begins in the key of B minor, evoking the opening of the “Unfinished” Symphony with which it shares not only the same key, but a similar bass motive. Susan McClary (1994, 225) describes the latter as an example of a victim narrative in which “a sinister affective realm sets the stage for the vulnerable lyrical subject, which is doomed to be quashed.”(2) One of the means by which Schubert creates this “affective realm” in “Der Doppelgänger” is through his careful choice of keys. Although references to key qualities abound, the topic has been largely neglected in our time until Rita Steblin’s (1983) A History of Key Characteristics in the Eighteenth and Early Nineteenth Centuries. Historically, the most influential work on this subject was probably the Ideen zu einer Asthetik der Tonkunst of Christian Schubart, written about 1784, and published posthumously in 1806. That Franz Schubert was familiar with the latter is likely, considering that he set four of Schubart’s poems to music, including the famous “Die Forelle.” However, as Steblin (1983, 190) states, “even composers who did not express their views on the matter might nevertheless be presumed to represent established tradition in their creative work.”

[5] It is intriguing to see how Schubart’s key characteristics relate to the music and text of “Der Doppelgänger.” Of B minor, the tonic key, Schubart (1806) states:

B minor. This is as it were the key of patience, of calm awaiting one’s fate and of submission to divine dispensation. For that reason its lament is so mild, without ever breaking out into offensive murmuring or whimpering. The use of this key is rather difficult for all instruments; therefore so few pieces are found which are expressly set in this key. (Steblin 1983, 124)

The affect of B minor, like the opening of the poem, is relatively calm, but it also foreshadows the “fate” to come. In contrast, B major represents “anger, rage, jealousy, fury, despair, and every burden of the heart”—emotions well suited for the ending of the poem (Steblin 1983, 123). The piece remains in B minor until the third stanza (measure 47), at which point it modulates, not to the dominant or relative major, but to the raised mediant. The modulation occurs at the precise moment in which the doppelgänger mocks the love-sorrows of the narrator. Based upon Schubart’s description, the choice of key could not have been more fitting:(3)

[D♯ ] minor. Feelings of anxiety of the soul’s deepest distress, of brooding despair, of blackest depression, of the most gloomy condition of the soul. Every fear, every hesitation of the shuddering heart, breathes out of horrible [D♯ ] minor. If ghosts could speak, their speech would approximate this key. (Steblin 1983, 122–23)

If Schubert had modulated to a different tonic, the affect of the key would have contradicted that of the poem.

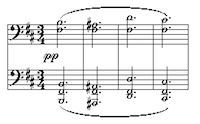

Example 1. Introduction to “Der Doppelgänger,” mm. 1–4

(click to enlarge)

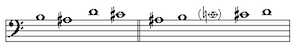

Example 2. Multiple implications of each dyad in mm. 1–4

(click to enlarge)

[6] Taken as a whole, the opening chord progression can be clearly heard as a half cadence (or at least an incomplete progression) in the key of B minor (see Example 1). Individually, however, none of the chords are complete, hence each dyad potentially implies more than one harmony (see Example 2). Without their thirds, the outer chords could be either major or minor triads: the first being I (B–

[7] In the first part of the poem, the narrator fills in the picture of the surroundings gradually—night, street, house, man—just as the empty chords themselves are completed slowly. In the first stanza (measures 5–24), virtually no action takes place in either the poem or the music. Most of the vocal notes which fill in the chords are set to relatively insignificant articles (e.g., die, diesem, das), and there is no harmonic development between the first and second stanzas. It is only with the appearance (in the poem) of the other man that the development of the music begins to advance. In measure 25 the voice begins on a new note, D, rather than

[8] The climax of the poem occurs at the end of the second stanza, when the narrator discovers that this other man is his double (“der Mond zeigt mir meine eig’ne Gestalt”). The revelation, in a sense, strips the narrator of his own identity, causing him to shudder (“mir graut es”). More importantly, this coincides with the first interruption of the note

[9] The relationship between the dominant and the subdominant forms one of the primary binary oppositions within the piece: one obsessively present, the other hauntingly absent. As with their poetic counterparts, the two terms are mirror images of each other, one major, the other minor. The root pitches themselves,

[10] It is a tribute to Schubert’s genius that all of the essential structural elements of “Der Doppelgänger” are contained within the opening four bars. The four-note motive B–

Example 3. Structural gap showing missing pitch C in opening motive

(click to enlarge)

Example 4. Structural gaps (missing pitches E and G)

(click to enlarge)

[11] The four-note motive, B–

[12] Although less significant than the dominant/subdominant pairing, the dual nature of the chords in the introduction also provides a complete (and circular) presentation of another binary opposition: the antithesis of major vs. minor. William Kinderman (1986, 75) suggests that in some of Schubert’s music “contrast between major and minor may represent one aspect of a more profound thematic juxtapositon suggesting the dichotomy of inward imagination and external perception.” In Heine’s poem, the latter is present in the narrator’s description of the physical house and street; the former in his remembrances of his sweetheart. Individually, each of the chords in the opening might also symbolize this opposition by implying both a major and minor triad (see Example 2). On a larger scale, the opening chord demarcates the dichotomy between the tonalities of B major and B minor. With this in mind, the succeeding chords can be interpreted as belonging to one or the other side of the major/minor wall: the second chord, because of its leading-tone

[13] Having presented (or, if you prefer, constructed) several issues in need of resolution, I would now like to pursue them through the remainder of the composition. All of the chords in the first section of the piece (measures 5–40) are derived from the pitches of the introduction and are likewise mostly incomplete within the piano part itself. One might expect the vocal line to supply the missing notes which complete the sonorities as the opening progression is repeated over and over. Nonetheless, while Schubert may have prematurely revealed the somber tenor of Heine’s poem, he defers revealing the ‘true’ quality of the opening chords as much as possible. The voice rarely enters on the downbeat thus creating the effect of a quasi-recitative, and its first entrance on the second beat of measure 5, of course, provides no additional information since the ![]()

[14] Harmonically, the next section (measures 15–24) is identical to the first, with the only difference being that the B natural in measure 17 comes in one-sixteenth of a beat earlier than its counterpart in measure 7. In the beginning of the second stanza, the vocal line reveals two more chords: i (measure 25) and V (measure 28), which correspond to the first and last dyads of the opening progression. Also of note, is the use of the piano motive B–

[15] In terms of the original progression, only three of the four chords can be identified. The second chord (the

[16] Starting in measure 43, one seems to hear the opening progression starting yet again, but it quickly turns in another direction. Instead of being abandoned, the progression begins to retrograde in measures 45–47. Upon reaching the third chord (originally the second), the

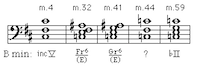

Example 5. Final version of opening progression, mm. 56–59

(click to enlarge)

Example 6. Occurrences of ‘missing’ C natural

(click to enlarge)

[17] In the end, one might expect for the ambiguity of the introduction to finally be resolved by filling in all of the chords. While the progression does seem to return in the piano postlude, it is not ‘filled in’, but rather altered to reveal a different type of resolution. The first three chords are the same as the opening (except for the added pitch D completing the first chord), while the last is replaced by a lowered II chord, (see Example 5). There are two important aspects associated with this change of chord. First of all, it is in the position of what should have been the dominant. Secondly, it contains all three of the missing pitches formed by the structural gaps. Thus, these pitches (C, G, and E) are also unequivocally bound to the fate of the dominant.

[18] Tracing the disintegration of the dominant harmony, I propose two separate (although interconnected) paths, both originating in measure 4, but leading to separate destinations. The first path is governed by the force of the missing C natural. There are just four occurrences of this pitch, and each is directly connected with the dominant (see Example 6). Lawrence Kramer (1986, 221) describes the role of C as “an unresolvable long-term dissonance independent of tonal organization.” In my version, however, the appearance of the C is not “unresolvable,” but rather it is the inevitable resolution of the structural gap posed at the opening. The first two times it appears as part of two different augmented-sixth chords (measures 32 and 41), both of which function harmonically as dominant substitutes, and physically replace the dominant-seventh chord heard in the previous statements of this progression (measures 13 and 23). Then, in measure 44, the C–

[19] The second path of the dominant’s demise, leading from measure 4 to measure 61, is a gradual transmutation integrating the missing pitches E and G with the symbolic antithesis of the dominant and subdominant. As I remarked earlier, from the beginning of the piece, the dominant is portrayed as weak, appearing as an empty fifth (measure 4), a minor triad (measure 10), and even as a bare octave (measure 10). Regarding the piece as a whole, Lawrence Kramer (1986, 220) notes that “the dominant triad remains incomplete except when the seventh is added.” The seventh of

[20] The transformation from dominant to subdominant is a dynamic movement which structures the piece. It is, like Elizabeth Bowen’s (1974, 170) description of the story, an “action towards an end not to be forseen (by the reader), but also toward an end which, having been reached, must have been from the start inevitable.” Looking back, we see the inevitability of the subdominant harmony first implied by the augmented-sixth chords shown in Example 6. Unlike the German-sixth of measure 51, these chords are not the augmented-sixths one would normally expect in the key of B. Rather, they are, respectively, the French- and German-sixth chords derived from the key of E. Therefore, although they function as dominant substitutes in the context of B minor, they imply a dominant preparation in the key of the E minor. Similarly, the modulation to

[21] At the close of “Der Doppelgänger,” the two antithetical elements of the piece become interrelated to create an ambiguous ending. Because of the added seventh (A natural), the B-major triad in measure 60 can only be interpreted as the dominant of E, thus belonging to the antithesis of the dominant/subdominant. However, the appearance of this chord fulfills the expectation for a B-major triad which was created in the first bar of the piece. This is the last of the eight potential chords of Example 3 to be realized and, thus, it also belongs to the dichotomy of B major/B minor. If the latter pairing is considered more important than the former, then the final two chords (measures 61–63) should be considered a kind of plagal cadence with a Picardy third. On the other hand, if the opposition of the dominant/subdominant is considered more significant, then these same chords might be construed as part of a cadence in E minor.(11) At the very least, one can state that the ending does not unambiguously resolve either of these large-scale harmonic concerns.

[22] Finally, the legend of the doppelgänger says that “to meet one’s wraith, or double, is a sign that one’s death is imminent.” (Encyclopaedia Britannica 1985, 182) Interpreting the music in this manner, the addition of the subdominant E (as the seventh of the dominant) in measure 12 might signal the imminent disintegration and ultimate replacement of the dominant. Moreover, if the principal character does in fact die at the end, then the final raised B-major chord could not be thought of as a positive resolution, but rather as a dark victory for the subdominant, which succeeds in subverting even the original tonic into its own dominant. The anguished, guilt-ridden death portrayed in “Der Doppelgänger” is even more poignant when juxtaposed against the prayer for peace and forgiveness of sins of the “Agnus Dei” with which it shares the principle motive.

[23] Following the model of other scholars, one could tie this musico-literary analysis to Schubert’s personal life. Cone 1982, 1984; Macdonald 1978; McClary 1994; Webster 1978) In his article, “Schubert’s Promissory Note,” Edward T. Cone (1982, 241) asks, “did Schubert’s realization of [the syphilis], and of its implications induce, or at least intensify the sense of desolation, even dread, that penetrates much of his music from then on?” Following this hypothesis, Cone relates the hermeneutic actions of the Moment Musical No.6, to Schubert’s contraction of syphilis. Similarly, one might view the gradual alterations of the dominant in “Der Doppelgänger” as representing the gradual affliction of the disease within Schubert himself. Musically this process exposes the previously absent pitches of the opening, fleshing out the dual identities of the chords. Similarly, Schubert’s affliction made public his previously concealed private life, revealing the two-sided nature of his personality. The song was dedicated to Schubert’s circle of friends with whom Schubert shared his secret life of pleasure and for whom a similar fate was likely in store. This reading of the song also maps well onto Heine’s text. Consider Schubert’s self-portrayal in a letter from 1824:

Imagine a man whose health will never be right again, and who in sheer despair over this ever makes things worse and worse, instead of better;. . . to whom the felicity of love and friendship have nothing to offer but pain at best. (Deutsch 1947, 339)

The disease may well have been Schubert’s own ‘doppelgänger’, painfully evoking the love-torment (‘Liebesleid’) of days gone by and signaling his imminent death just a few months following the composition this song.

Word-by-Word translation of text for “Der Doppelgänger”

Still ist die Nacht, es ruhen die Gassen,

Still is the night, it sleeps the streets,

in diesem Hause wohnte mein Schatz;

in this house lived my sweetheart;

sie hat schon løngst die Stadt verlassen,

she has already long [ago] the town left.

doch steht noch das Haus auf demselben Platz.

yet stands still the house on the same place.

Da steht auch ein Mensch, und starrt in die Høhe,

There stands also a man, and stares into the height.

und ringt die Hønde vor Schmerzensgewalt;

and wrings the hands for grief-violence,

mir graust es, wenn ich sein Antlitz sehe,

[to] me shudders it, when I his face see,

der Mond zeigt mir meine eigne Gestalt

the moon shows me my own form.

Du Doppelgänger, du bleicher Geselle!

You double-goer, you pale companion!

Was øffst du nach mein Liebesleid,

Why ape [mimic] you after my love’s-suffering

das mich gequølt auf dieser Stelle

that me tormented at this place

so manche Nacht, in alter Zeit?

so many [a] night, in old time?

David Løberg Code

Western Michigan University

School of Music

Kalamazoo, MI 49008

code@wmich.edu

Works Cited

Bowen, Elizabeth. 1974. Pictures and Conversations. New York: Knopf.

Brody, Elaine and Robert Fowkes. 1971. The German Lied and its Poetry. New York: New York University Press.

Cone, Edward T. 1984. “Schubert’s Unfinished Business.” 19th Century Music 7, no. 3: 222–232.

—————. 1982. “Schubert’s Promissory Note: An Exercise in Musical Hermeneutics.” 19th Century Music 5, no. 3: 233–241.

Deutsch, Otto Erich. 1978. Franz Schubert: Thematisches Verzeichnis. Kassel: Baerenreiter-Verlag.

—————. 1958. Schubert: Memoirs by His Friends (trans. Ley and Nowell). London: Dent.

—————. 1947. The Schubert Reader (trans. Blom). New York: Norton.

Encyclopaedia Britannica. 1985. “Doppelganger.” In The New Encylcopaedia Britannica, 15th edition. Chicago: Encyclopaedia Britannica, Inc., 182.

Goldschmidt, Harry. 1974. “Welches war die urspruenglische Reihenfolge in Schuberts Heine-Liedern.” In Deutschers Jahrbuch der Musikwissenschaft fuer 1972. Leipzig.

Kinderman, William. 1986. “Schubert’s Tragic Perspective.” In Schubert: Critical and Analytical Studies, ed. Frisch, 65–83. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.

Kramer, Lawrence. 1986. “The Schubert Lied: Romantic Form and Romantic Consciousness.” In Schubert: Critical and Analytical Studies, ed. Frisch, 200–236. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.

Kramer, Richard. 1985. “Schubert’s Heine.” 19th-Century Music 8, no. 3: 213–235.

Macdonald, Hugh. 1978. “Schubert’s Volcanic Temper.” Musical Times 119: 949–52.

McClary, Susan. 1994. “Constructions of Subjectivity in Schubert’s Music.” In Queering the Pitch, eds. Brett, Thomas, and Wood), 205–234. New York: Routledge.

Meyer, Leonard B. 1956. Emotion and Meaning in Music. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Sams, Eric. 1980. “Schubert’s Illness Re-examined.” Musical Times 121: 15–22.

Schubart, Christian. 1806. Ideen zu einer Aesthetik der Tonkunst. (Cited in Steblin 1983, 124).

Solomon, Maynard. 1993. “Schubert: Some Consequences of Nostalgia.” 19th- Century Music 17, no. 1: 34–46.

—————. 1989. “Franz Schubert and the Peacocks of Benvenuto Cellini.” 19th-Century Music 12, no. 3: 193–206.

Steblin, Rita. 1983. A History of Key Characteristics in the Eighteenth and Early Nineteenth Centuries. Ann Arbor, Michigan: UMI Research Press.

Stein, Jack M. 1971. Poem and Music in the German Lied from Gluck to Hugo Wolf. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.

Thomas, Werner. 1954. “Der Doppelgaenger von Franz Schubert.” Archiv fur Musik-Wissenschaft 11, no. 3: 253.

Webster, James. 1978. “Schubert’s Sonata Form and Brahms’s First Maturity.” 19th-Century Music 2, no. 1: 18–35.

Footnotes

1. The poem and a rather literal word-by-word translation is found at the end of this essay.

Return to text

2. McClary (1994, 226) further suggests that this type of narrative might reflect Schubert’s “sense of estrangement from former good times and his immersion in [the] ‘miserable reality’ [of his later life].”

Return to text

3. Following Steblin, I have appropriated Schubart’s description of

Return to text

4. It is also possible to consider this chord as a dominant with 6–5 appoggiatura (i.e., the D behaves like a temporary displacement of the dominant’s 5th,

Return to text

5. Richard Kramer (1985, 220) reveals that the original music accompanying “Gestalt” in the autograph was virtually the same as that accompanying “Schmerzensgewalt” (measures 31–33). Thus, the

Return to text

6. I realize, of course, that the pitch

Return to text

7. Werner Thomas (1954, 260) has proposed that the vocal part actually begins in a separate meter, starting with a ‘downbeat’ in

Return to text

8. Lawrence Kramer (1986, 220), however, suggests that the third chord of the progression is a III chord in B minor.

Return to text

9. One might also consider the abrupt change in vocal timbre resulting from the drop from G5 to

Return to text

10. Furthermore, with the exception of measure 55, the pitch E never occurs as a chord tone in the vocal part.

Return to text

11. I personally hear the ending as a cadential six-four progression in E minor, which is suspended (by a fermata) before reaching its final tonic in some netherworld beyond the double bar. It is also interesting to note that the B–

Return to text

Copyright Statement

Copyright © 1995 by the Society for Music Theory. All rights reserved.

[1] Copyrights for individual items published in Music Theory Online (MTO) are held by their authors. Items appearing in MTO may be saved and stored in electronic or paper form, and may be shared among individuals for purposes of scholarly research or discussion, but may not be republished in any form, electronic or print, without prior, written permission from the author(s), and advance notification of the editors of MTO.

[2] Any redistributed form of items published in MTO must include the following information in a form appropriate to the medium in which the items are to appear:

This item appeared in Music Theory Online in [VOLUME #, ISSUE #] on [DAY/MONTH/YEAR]. It was authored by [FULL NAME, EMAIL ADDRESS], with whose written permission it is reprinted here.

[3] Libraries may archive issues of MTO in electronic or paper form for public access so long as each issue is stored in its entirety, and no access fee is charged. Exceptions to these requirements must be approved in writing by the editors of MTO, who will act in accordance with the decisions of the Society for Music Theory.

This document and all portions thereof are protected by U.S. and international copyright laws. Material contained herein may be copied and/or distributed for research purposes only.

Prepared by Cara Stroud, Editorial Assistant