The Bridges that Never Were: Schenker on the Contrapuntal Origin of the Triad and Seventh Chord

Eytan Agmon

KEYWORDS: Schenker, counterpoint, triad, seventh chord, harmony, hierarchy

ABSTRACT: Schenker’s success in bridging the gap between strict counterpoint and free composition is reassessed, in view of the finding that in each of these two domains the notions “triad” and “seventh chord” assume qualitatively different meanings.

Copyright © 1997 Society for Music Theory

1. Introduction

2. The Consonance Principle

3. The Triad in Strict Counterpoint

4. The Seventh Chord in Strict Counterpoint

5. Conclusion

6. Appendix: Beyond the Harmony/Voice-Leading Dichotomy

1. Introduction

[1.1] In view of his well-known belief that

“voice-leading must

always and everywhere be regarded as the actual foundation

of music,”(1) it is instructive to

learn that, in Counterpoint, Schenker sets as his “first task

[1.2] As Schenker is quick to realize, however,

“precisely such a

clear-cut discrimination between the ‘exercise’ and the free

work of art makes all the more imperative a second task,

namely

[1.3] In the present essay I shall question the existence of two specific such bridges. In particular, I shall claim that the triad and seventh chord of free composition, as harmonic entities, are qualitatively distinct from the “triad” and “seventh chord” of strict counterpoint; the gap between the harmonic and contrapuntal meanings of the terms “triad” and “seventh chord,” in other words, simply cannot be bridged. Schenker is of course aware that the seventh chord is a potential problem, for he devotes a special section to the “budding” seventh chord, as he calls it, in the last part of Counterpoint, a part entitled, appropriately enough, “Bridges to Free Composition.” Schenker seems less aware, however, that even to derive the “simple” triad from purely contrapuntal assumptions is highly problematic.

[1.4] It should be stressed that not all of Schenker’s bridges are of questionable status; as Schenker insightfully suggests in “Bridges to Free Composition,” combined species may be viewed in hierarchical terms.(5) Combined species, in other words, may be viewed as a bridge between strict counterpoint and free composition as far as such notions as “structural level,” “prolongation,” or the Stufe, are concerned. Nonetheless, I believe that the failure of Schenker’s bridges in the cases of the triad and seventh chord has far-reaching theoretical implications. I shall consider these implications in an appendix to the present essay.

2. The Consonance Principle

[2.1] Contrapuntal theory, for Schenker, may be reduced to one fundamental premise, reiterated time and again (in one version or another) throughout the two volumes of Counterpoint: “In the beginning is consonance! The consonance is primary, the dissonance secondary!”(6) I shall refer henceforth to this principle as the “Consonance Principle” (CP).

[2.2] How, exactly, does Schenker classify vertical dyads as consonant and dissonant? As it turns out, Schenker uses more than one system of classification. By one method, to which I shall refer henceforth as CP1, the consonances are either perfect (perfect octave and fifth), or imperfect (major or minor third and sixth); all other intervals (augmented fourth, diminished fifth, major or minor second or seventh)—except the perfect fourth—are always dissonant. By CP1 the perfect fourth has special status. Originally a perfect consonance, the interval becomes a dissonance when formed in relation to the bass.(7)

[2.3] According to another method, to which I shall refer henceforth as CP2, intervals are only counted in relation to the bass. The perfect fourth, by CP2, is dissonant. However, since intervals in the upper parts are in a sense nonexistent, it is irrelevant whether they are consonant or dissonant. Thus, the intervals perfect fourth, augmented fourth, diminished fifth, major or minor second or seventh, may be freely used in the upper parts as if they were consonant. It should be stressed that Schenker never explicitly distinguishes between CP1 and CP2. For example, after explaining that the perfect fourth “realizes its original potential as a consonance” when formed in the upper parts (CP1), he mentions as an afterthought that a similar allowance must be made for the augmented fourth as well, even though the interval was never “originally” a consonance (CP2).(8) There is some evidence in Counterpoint that CP2 is Schenker’s preferred system of consonance/dissonance classification;(9) and yet, in deriving the triad in volume 2, Schenker seems to be using CP1 and CP2 interchangeably.

3. The Triad in Strict Counterpoint

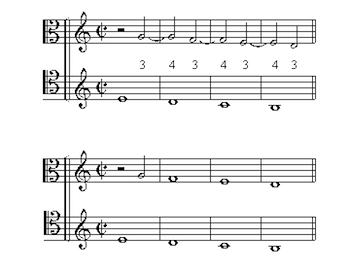

[3.1] In his discussion of three-voice

counterpoint, first species,

Schenker states that “to the extent that the three

[simultaneous-sounding] tones of the counterpoint are to be

of different pitch, the law of consonance itself (cf. Part 2,

Chapter 1) restricts polyphony of three voices to ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

[3.2] Schenker begins the subsequent section with

the following

statement: “Since the concept of triad was thus restricted, for

the domain of three-voice counterpoint, to ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

[3.3] Schenker’s contrapuntal derivation of the

triad is

problematic on several counts. First, although he seems to

settle for CP2 in the end, his vacillation between CP1 and CP2

is plainly unacceptable. Second, as a “law of consonance,”

CP2 leaves much to be desired. While it is true that, say,

(d1,f1,b1) sounds much better than (b,d1,f1), it is nonetheless

rather doubtful that one could count the diminished ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

[3.4] Although each of the above objections is quite serious, a

much more sweeping objection may be made with regard to

deriving the notion “triad” from contrapuntal assumptions in

general, be they CP1, CP2, or any other conceivable

“Consonance Principle.” For the triad of free composition is

defined independently of the quality of the intervals of

which it is comprised (major, minor, etc.), so that, for

example, not only are (C,E,G) and (C,

[3.5] Note that what is at stake here is not merely that strict

counterpoint excludes the diminished and augmented

sonorities from the domain of “triads” (altogether by CP1, in

root position as well as second inversion by CP2); after all,

one might argue, of the seven diatonic triads only one is

diminished, and none is augmented (the augmented triad may

arise only as a result of chromatic alteration). Rather, what is

at stake is a much more fundamental issue, namely, that the

triad of free composition, in principle, cannot be equated with

the “triad” (i.e., “consonant three-tone sonority”) of strict

counterpoint. There exists, in other words, a qualitative

difference between the two concepts, regardless of how

often specific manifestations of either may happen to

coincide in practice. Even by CP2, which allows the

diminished as well as augmented ![]()

![]()

![]()

[3.6] It is instructive that Schenker does refer

to the

diminished ![]()

4. The Seventh Chord in Strict Counterpoint

[4.1] Unlike the major and minor triads, any root-position seventh chord violates CP, and thus has no independent status in strict counterpoint.(17) Schenker, therefore, explicitly relegates the discussion of the seventh chord to the concluding part of his treatise, a part that he designates by the highly suggestive title “Bridges to Free Composition.” “Bridges,” as is well known, is an essay on combined species. The “budding” seventh chord, as Schenker calls it, is considered in the context of three-voice counterpoint, combining fourth-species counterpoint (suspensions) with second species.

[4.2] It is not difficult to see why Schenker opted to derive his “budding” seventh chord from a combination that specifically includes a fourth-species part (rather than, say, a combination of two second-species parts). The treatment of the seventh in fourth-species counterpoint is suggestive of free composition on two important counts: (1) the seventh resolves downwards; (2) the seventh appears on the downbeat, and thus seems to have a more independent status than, say, a passing seventh on the weak beat. The first of these two considerations is not really relevant to the present discussion, which focuses on the conceptual status of the seventh chord as a vertical formation, and not on how a seventh chord may or may not interact with its neighboring harmonies.

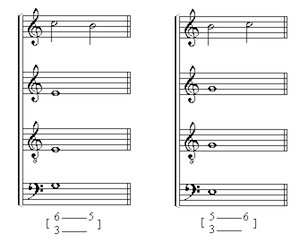

[4.3] It is important to emphasize how crucial

for Schenker in

this context is the distinction between a suspended seventh on

the strong beat and a passing seventh on a weak beat. Thus

for example, in connection with the suspended ![]()

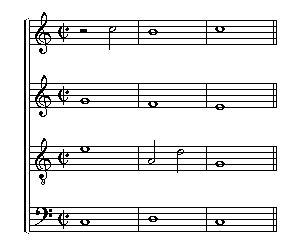

Figure 1a. From J. J. Fux, “The Study of Counterpoint.” Figures 63–64 (page 56)

(click to enlarge and listen)

Figure 1b. From J. J. Fux, “The Study of Counterpoint.” Figures 135–36 (page 94)

(click to enlarge and listen)

[4.4] Since Schenker insists that his “budding” seventh chord is a child of fourth-species counterpoint, we might as well take a look at Fux’s Gradus ad Parnassum to review the special problems of dissonance treatment that this species poses. In Fux’s treatise, there is no separate treatment of combined species; yet the treatise does include some suggestive references to dissonance treatment in the context of fourth species combined with second species. Before turning to these specific references, however, let us listen to Fux on fourth species in ordinary two- and three-part counterpoint.

[4.5] Concerning the status of dissonance in fourth-species counterpoint, Fux’s rule is straightforward: “ligatures do not change anything.”(20) In other words, the dissonance, despite its appearance on the downbeat, has no independent status; only the consonance to which the dissonance resolves has independent status. It is therefore conceptually possible to disregard the dissonance altogether, as though the consonance occupied the entire measure in the manner of a first-species exercise. Fux illustrates the idea that first species conceptually underlies fourth species—at least as far as the status of consonance is concerned—in both the two- and three-part contexts.(21) Fux’s examples—given here as Figures 1a and 1b—are quoted by Schenker.(22)

[4.6] Fux reiterates the rule that “as to the

consonances,

Joseph.— Does this rule always hold, revered master?

Aloys.—It does not hold in some instances of this species in which the ligatures must sound well together with three whole notes for the duration of a full measure. The commonest instance in which this cannot be brought about is when the seventh is used together with the fifth in the ligature, e.g.: [see Figure 2a] If the ligature were removed, a dissonance with the tenor would result which is faulty and decidedly to be avoided.

Joseph.—What can one do in this case?

Aloys.—One must divide the whole note in the tenor part, thus: [see Figure 2b](24)

|

Figure 2a. “The Study of Counterpoint,” Figure 190 (page 129) (click to enlarge and listen) |

Figure 2b. “The Study of Counterpoint,” Figure 191 (page 129) (click to enlarge and listen) |

Figure 2c. Figure 2b, with the suspension revoked

(click to enlarge and listen)

Figure 3a. “The Study of Counterpoint,” Figure 197 (page 132)

(click to enlarge and listen)

Figure 3b. Measures 3 and 5 of Figure 3a, with the suspensions revoked

(click to enlarge and listen)

Figure 3c. “The Study of Counterpoint,” Figure 198 (page 133)

(click to enlarge and listen)

[4.7] Now, it is pretty obvious that Aloys’s solution to the conceptual downbeat-dissonance (a ninth a–b1) between the tenor and soprano, namely, a momentary combination of fourth species with second species, is no solution at all, since the conceptual dissonance prevails despite the movement in the tenor, as Figure 2c makes abundantly clear. In his treatise, Schenker quotes this passage from Fux without comment.(25)

[4.8] At the same time, Schenker launches a

scathing attack

on Fux in connection with a related passage appearing only a

few pages later. According to Schenker, in this second

passage (to which I shall turn shortly) Fux’s “lack of a clearly

defined insight

[4.9] Note that in two instances—measure 3 and measure 5—Fux violates the purity of the species by introducing half-note motion in the top voice. Significantly, however, unlike the half-note motion in Figure 2b, these motions are fully compatible with the rule that “ligatures do not change anything”; as shown in Figure 3b, the removal of the suspended tone in favor of its resolution reveals two completely consonant configurations, 6–5 and 5–6. At the same time, it seems that Fux could have hardly resisted noting that the vertical combination in the first half of measure 5 corresponds to an incomplete seventh chord in third inversion. As Aloys explains, “in the fifth measure of the last example the second is doubled while the sixth which is required for an absolutely perfect harmony is missing—as the following example shows: [see Figure 3c].”(29)

[4.10] Now, Schenker is of course correct in criticizing Fux for referring to a seventh chord as “an absolutely perfect harmony” in the context of strict counterpoint;(30) and yet, if Fux indeed believed that an inner-voice D on the downbeat of measure 5 would have been so advantageous, what could have possibly prevented him from having it in his example in the first place? Surely not the purity of the species.(31) Schenker may have found Fux’s passage to be so disturbing precisely because it seems to force a choice between two incompatible alternatives: either a seventh chord is a “harmony” in its own right, in which case the Consonance Principle must be abandoned, or else the seventh chord cannot exist as such in strict counterpoint, even in combined species.

[4.11] This brings us, finally, to Schenker’s “budding” seventh chord. As William Clark correctly observes, Schenker’s distinction between two types of suspensions, only one of which is “authentic,” is crucial in this connection.(32) The syncopes 7–6 (upper part), as well as 2–3 and 4–5 (lower part), cannot be considered authentic according to Schenker, because they “raise doubt about whether the harmony of the downbeat still continues at the third (final) time-unit or whether, because of the interval 6 in the upper (or 3 or 5 in the lower) counterpoint, a second harmony should not perhaps be assumed.”(33)

[4.12] This statement, however, deserves close scrutiny. Given

a suspension such as 7–6 in the upper part, what could

possibly raise doubt as to the identity of the harmony on the

weak beat? By CP, the seventh has no independent status, and

therefore the interval of the sixth conceptually underlies the

entire measure. Since the interval of the sixth, in strict

counterpoint, can be associated with only one “harmony,”

namely a (consonant) ![]()

![]()

[4.13] Since the traditional rules of strict counterpoint no longer seem to apply, the identity of Schenker’s downbeat harmony is anybody’s guess. Nonetheless, it is fairly clear that the downbeat harmony cannot contain the sixth of the weak beat, since Schenker sees precisely this sixth as the principal agent of harmonic change. But this means that the seventh of the downbeat must be counted as an essential component of the assumed harmony. That is to say, the seventh must be considered an essential dissonance.

[4.14] It thus turns out (not quite surprisingly, I would maintain) that Schenker’s distinction between the two types of suspensions is but a thinly-disguised version of Kirnberger’s (and/or Schulz’s) epoch-making distinction between “non-essential” and “essential” dissonance.(34) Kirnberger’s distinction is epoch-making precisely because it implies that the seventh chord of free composition is a qualitatively-different entity from the suspended-seventh formations of fourth-species counterpoint. The seventh chord of free composition, in other words, must be assumed as a harmonic entity in its own right. For Schenker, to openly admit that the seventh chord embodied an essential dissonance is of course out of the question, for such an admission would fly in the face of CP. This ambivalence results in some of the most outrageously self-contradictory prose ever committed to paper by a music theorist.

[4.15] Consider, for example, the following sequence of ideas, which appear in close succession in the opening paragraph of “The budding seventh-chord.”(35)

(1) “If we now place the syncopes <previously> described

(2) “The seventh-chord <of free composition>

(3) “The so-called seventh-chord <of free composition>

(4) “(The passing tone, however, relinquishes nothing of its independence <sic!> through the fact that it moves forward to another, no less independent, sound.)”

(5) “Nevertheless, there is certainly still a considerable difference between the seventh-chord of free composition and the syncope-settings named above.”

Now, the only possible sense that one might make of this wild collection of ideas is something like the following statement: “Despite its superficial resemblance to the suspension-formations of strict counterpoint, the seventh chord of free composition [idea no. 1] is not a suspension formation at all [ideas no. 2 and 5]; rather, the seventh chord of free composition is a passing-tone formation [idea no. 3], however, a passing-tone formation of a very special type, unfamiliar to strict counterpoint [idea no. 4].” But clearly, if this is really what is meant (especially with regard to the amazing parenthetical reference to the alleged independence of the passing tone), then Schenker’s prose is simply a highly convoluted way of saying that the seventh chord of free composition is qualitatively distinct from the quasi seventh-chord formations (whether of fourth species or second-species origin) of strict counterpoint. The “bridge” between strict counterpoint and free composition simply does not exist.

[4.16] Or consider the following statement,

where Schenker, in

trying to account for the suspended ![]()

[4.17] A natural reaction to Schenker’s hopelessly confused account of the “budding” seventh chord—especially by someone who is not particularly sympathetic to his ideas in the first place—would be to give him a good taste of the arrogant and condescending attitude that he repeatedly expressed towards his fellow theorists. After all, was it not Schenker himself, at the very outset of Counterpoint, who ridiculed his colleagues (especially, Rameau and Riemann) by comparing them to children playing with dolls?(37) Yet what can be more childish than Schenker’s make-believe world where blatant contradictions do not seem to count?

[4.18] Nonetheless, I believe that such a reaction, although not totally unjustified, would miss the point. What it fails to take into account is the extraordinary finding that Schenker clings to the fourth-species model even though he seems to know perfectly well (as the excerpts quoted above strongly suggest) that a second-species model, combined with the simple notion of contraction, could have saved him a lot of trouble. What could be the possible reason for Schenker’s self-defeating stubbornness in this case?

[4.19] I believe that in light of all the available evidence, there can be only one convincing answer to this question. Schenker was genuinely torn between his commitment to the Consonance Principle, on the one hand, and his awareness, on the other, that the seventh chord of free composition embodied an essential dissonance, a dissonance which, in good faith, simply cannot be explained in the terms of contracted passing motion. Schenker’s convoluted prose, therefore, is the product of a tormented mind. One can only nod one’s head in sympathy when Schenker, in the very same paragraph from “The budding seventh-chord” where he refers to “that authentic seventh,” stamps his foot and reasserts the premise upon which his entire treatise is based: “Thus I repeat once more: In the beginning is consonance! It is consonance alone that carries within itself the fundamental laws of suspensions!”(38) Indeed, I believe that the conflict between the authentic seventh and the Consonance Principle is one that Schenker was never able to resolve. As is well known, in Free Composition Schenker rules out a priori a composing-out of “the dissonant passing tone, including the passing seventh”; yet just a few pages later he discusses examples that “show the composing-out of a seventh chord.”(39)

[4.20] I take it as a tribute to Schenker’s

intellectual integrity

that, at least in Free Composition, he made little effort to

smooth-out the contradiction. It is therefore most unfortunate

that some of his followers have attempted to do just that.

William Clark, in particular, explains some of Schenker’s

seventh-chord prolongations in terms of implied 8–7 passing

motion;(40) where this explanation

seems to fail, Clark

concedes that “the seventh chord

5. Conclusion

[5.1] I began the present essay by referring to the two goals that Schenker sets forth at the outset of Counterpoint: first to separate the study of counterpoint from composition, and only then to reveal their connection. There can be little doubt that Schenker was highly successful as far as the first goal is concerned. However, I believe his success in achieving the second goal must be seriously reassessed. Schenker believed that the “great gulf” between strict counterpoint and free composition may be bridged. Yet at least in two important cases—the triad and seventh chord—this belief does not seem to hold under scrutiny. Contrapuntal theory, by definition, simply cannot escape the constraints of the Consonance Principle, however ingenious the maneuvers one may devise to do so. It is high time to face this fact courageously and to draw the necessary conclusions from it. For surely there exist alternatives to Schenker’s contrapuntally-based theory of tonality, a theory of bridges that never were.

6. Appendix: Beyond the Harmony/Voice-Leading Dichotomy

I. Verticalism and Horizontalism

[6.1] In Traité de l’harmonie, Rameau states that “melody is only a consequence of harmony.”(42) For Schenker, on the other hand, as Carl Schachter has stated, “counterpoint is logically prior to harmony and not the other way around.”(43) Schenker expressed this dependency very clearly in the Preface to Kontrapunkt, although he emphasized its historical, rather than conceptual, aspect: “All musical technique is derived from two basic ingredients: voice leading and the progression of scale degrees. Of the two, voice leading is the earlier and more original element.”(44) I shall refer to these two opposing views concerning the relative priority in tonal theory of harmony versus counterpoint as “verticalism” (harmony before counterpoint) and “horizontalism” (counterpoint before harmony).

[6.2] If “triad” and “seventh chord,” as asserted in the preceding essay, cannot be defined in contrapuntal terms, counterpoint simply cannot be logically prior to harmony. This conclusion, however, raises at once a number of questions. First, if horizontalism is indeed so fatally flawed, why do Schenker’s horizontalist views seem so compelling nonetheless? And second, what are the theoretical consequences of abandoning such views? In particular, does abandoning horizontalism necessarily mean that one must subscribe to the rival, verticalist approach instead? Such questions are taken up below.

II. Horizontalism and Hierarchical Structure

[6.3] It is instructive that commentators on

Counterpoint,

and especially on “Bridges,” have tended to accept Schenker’s

contrapuntal derivation of the triad and seventh chord

uncritically, and focused instead on the hierarchical

implications of combined species.(45) As Schenker pointed out, combined species is extremely suggestive as far as

hierarchy is concerned, for “when several passing tones occur

simultaneously, they join together in a kind of obbligato

two-voice setting—that is, for the sake of their own

clarification, they cultivate the consonance as the law of their

relationship

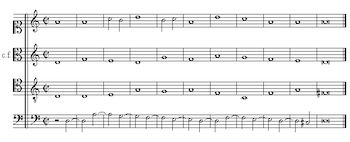

Example 1. Mozart, K.V. 550, measures 28–33 (strings only)

(click to enlarge and listen)

Figure 4a. Two harmonic analyses of Example 1

(click to enlarge)

Figure 4b. Two harmonic analyses of Example 1

(click to enlarge)

Example 2. Mozart, K.V. 550, measures 211–16 (strings only)

(click to enlarge and listen)

[6.4] There can be little doubt that Schenker’s hierarchical conception of combined species is an extremely valuable contribution to contrapuntal theory,(47) and that the notion of tonal hierarchy, in itself, is profound. What cannot be accepted, however, is the implication that tonal hierarchy, in general, is conceivable only in contrapuntal terms. When Carl Schachter, for example, states in connection with his combined-species model of Chopin’s E-minor Prelude that “the Prelude is notoriously resistant to a chord-by-chord ‘harmonic’ analysis,”(48) I take it that the emphasis is on “chord-by-chord”—a primitive, uni-leveled harmonic analysis. John Rothgeb is even more straightforward in this respect. In connection with a passage from Mozart’s G-minor Symphony, given here in reduced score (strings only) as Example 1, Rothgeb not only states that “the chords in bars 28–33 are in no way intended to express a harmonic progression,” but goes so far as to imply that it is wrong to regard “those passing sonorities” as triads.(49)

[6.5] However, there already exists a theory—“functional Auskomponierung”—where hierarchy is conceived in exclusively functional-harmonic terms.(50) Let me briefly demonstrate how such a theory might deal with “those passing sonorities” of Mozart’s Symphony.(51)

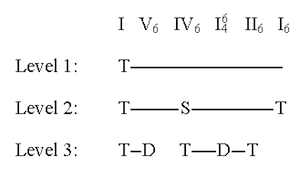

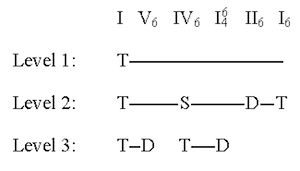

[6.6] Figure 4a presents one possible analysis. The I Stufe that underlies the entire passage is prolonged at a lower level by means of a plagal progression I–IV–I (T–S–T). This plagal progression is elaborated at a still lower level by means of two different authentic progressions. The opening I is elaborated by means of an incomplete authentic progression T–D (cf. Salzer’s “backward-relating” dominant). The IV, on the other hand, is prolonged by means of a complete authentic progression T–D–T; however, the final tonic is represented by II, not IV (cf. I–V–VI).

[6.7] Another, possibly more interesting

analysis is given in

Figure 4b. Applying the notion that II is weakly dominant,(52)

the figure shows a T–S–D–T progression at the intermediate

level. Example 2 shows the statement of this passage

in G minor in

the recapitulation. Note that the ![]()

III. Tonal Theory: A Non-Horizontalist View

[6.8] If strict counterpoint cannot account for triads and seventh chords, and moreover there exists no necessary connection between counterpoint and hierarchy, it is clearly pointless to hold on to a horizontalist view of tonality. But once horizontalism is abandoned and the seventh chord is accepted as a harmonic entity in its own right, the Consonance Principle (CP) must also be abandoned; and it also seems that there is no other choice but to subscribe to the rival, verticalist view where harmony is seen as conceptually prior to counterpoint. These two consequences (or apparent consequences) of adopting a non-horizontalist viewpoint shall be examined in the present section.

[6.9] What are the theoretical consequences of accepting the seventh chord, in violation of CP, as a harmonic entity in its own right? William Clark believes (following Schenker) that such a move would mean “the breakdown of the distinction between consonance and dissonance, which in turn implies the passing of the old harmonic order—the tonal system upon which the music of the masters of the past was based.”(54) Clark does not seem to realize that, following the same logic, even to admit the plain triad as a harmonic entity would entail such theoretically disastrous consequences, at least insofar as the diminished triad (and arguably also the augmented triad) is regarded as a harmonic entity. In any event, it is clear that Clark’s concern is justified only if the set of consonant intervals is taken as the total intervallic content of one’s harmonic entities (for example, if one recognizes as harmonic entities only the major and minor triads, then the consonant intervals would be the perfect prime, fourth, and fifth, as well as the major and minor third and sixth).

[6.10] But there is absolutely no reason to define “consonance” in just this particular way. A possible alternative is to take as “perfect” consonances those intervals whose special structural status must be assumed in defining the notion “diatonic system”: the perfect octave as the agent of “octave equivalence,” and the perfect fifth (or fourth) as the system’s “cyclic generator.”(55) Thirds and sixths assume special status (also as cyclic generators) at a lower level, a level where the notion “harmonic entity” (ultimately, the triad and seventh chord) is defined;(56) hence the “imperfect” consonances. “Consonant interval” defined in this way is not identical to the total intervallic content of all (diatonic) triads and seventh chords.

[6.11] One notable consequence of adopting such an approach is that verticalism is no longer the only viable alternative to horizontalism. For the notions “triad” and “seventh chord” are derived from assumptions that include both a harmonic and a voice-leading component.(57) In the conceptual rivalry between the vertical and the horizontal, in other words, neither dimension is necessarily prior to the other; both dimensions may be conceived simultaneously, so that it ultimately becomes impossible to refer to one without implying the other.

[6.12] Thus, in the final analysis, the perennial harmony/voice-leading dichotomy is revealed false. Perhaps this is a case worth remembering. For often it is much easier to fuel the flames of controversy than to attempt to break its vicious circles loose.

Eytan Agmon

Department of Musicology

Bar-Ilan University Ramat-Gan

Israel, 52900

agmone@ashur.cc.biu.ac.i

Footnotes

1. Heinrich Schenker, Free Composition, trans. and

ed. by Ernst Oster

(New York: Longman, 1979), 16

Return to text

2. Heinrich Schenker, Counterpoint, trans. by John

Rothgeb and

ü, ed. by John Rothgeb (New York: Schirmer, 1987), vol. 1,

10. Throughout this essay, my own interpolations into Schenker’s text

shall be enclosed by angle brackets < >, as distinguished from the

square

brackets [ ] within which Rothgeb’s original interpolations are

enclosed.

Return to text

3. Ibid., 2.

Return to text

4. Ibid., 10.

Return to text

5. For further discussion, see paragraph [6.3].

Return to text

6. Counterpoint, vol. 1, 111.

Return to text

7. See Counterpoint, vol. 1, 112–14. Although Schenker begins by

classifying

the

perfect fourth as a dissonance (page 112), subsequently he states that

the

interval may realize “its original potential as a consonance” (page 113).

As

the discussion on page 114 makes clear, the fourth reverts to its

original

consonant status when formed in the upper parts.

Return to text

8. Counterpoint, vol. 1, 114.

Return to text

9. See especially Schenker’s critique of Bellermann’s

consonance/dissonance classification in vol. 1, 120–22. See also his

reference in vol. 2, 101, to “the principle that all intervals are

conceived only in relation to the bass even in three-voice

counterpoint

Return to text

10. Counterpoint, vol. 2, 1–2 (emphasis

added).

Return to text

11. Ibid., 2 (emphasis added).

Return to text

12. Ibid., 3 (emphasis added).

Return to text

13. Cf. Salzer and Schachter, Counterpoint in

Composition, 27:

“Often the diminished ![]()

![]()

![]()

Return to text

14. Counterpoint, vol. 2, 2. Cf. Rothgeb, “Strict

Counterpoint and

Tonal Theory,” 282: “In the ![]()

![]()

Return to text

15. Counterpoint, vol. 2, 3.

Return to text

16. Rothgeb attempts in a footnote to rescue some sense

out of this

statement by explaining that the remark “triads

Return to text

17. Given that any root-position seventh chord violates

CP2 as well as

CP1, it seems pedantic to continue to employ the distinction between

the

two versions of Schenker’s Consonance Principle. Through the

remainder of this essay, therefore, reference shall be made only to

“CP,”

with no further qualification.

Return to text

18. Counterpoint, vol. 2, 216 (emphasis

added).

Return to text

19. See, for example, Counterpoint, vol. 1,

266–67.

Return to text

20. Johann Joseph Fux, “The Study of Counterpoint” from

Gradus ad

Parnassum, trans. and ed. by Alfred Mann (New York: Norton, 1965),

96.

Return to text

21. “The Study of Counterpoint,” 56, 94.

Return to text

22. Counterpoint, vol. 1, 269; vol. 2, 104.

Return to text

23. “The Study of Counterpoint,” 127; see Figures

187–89.

Return to text

24. Ibid., 128–29 (emphasis added).

Return to text

25. Counterpoint, vol. 2, 155–56.

Return to text

26. Ibid., 158.

Return to text

27. Ibid. (emphasis added).

Return to text

28. “The Study of Counterpoint,” 131–34.

Return to text

29. Ibid., 132–33 (emphasis added).

Return to text

30. Counterpoint, vol. 2, 158. Mizler’s German

translation of Fux’s

treatise, which was Schenker’s main source, uses the more neutral

phrase

“vollkommenen Harmonie.” See page 117 in the facsimile edition

(Hildesheim: Georg Olms, 1974).

Return to text

31. See, however, “The Study of Counterpoint,” measure 9 in Figure 195 (page

131). As Fux explains (page 130), in four-part counterpoint, fourth

species,

one frequently finds “instances where, on account of a series of

preceding

or following notes, the octave cannot be employed and the fifth must

necessarily be used.” The fifth, in other words, may be used only as a

last

resort.

Return to text

32. William Clark, “Heinrich Schenker on the Nature of the Seventh

Chord,” Journal of Music Theory 26:2 (1982), 225. I shall have

more to say about Clark’s essay later.

Return to text

33. Counterpoint, vol. 2, 85.

Return to text

34. See David Beach and Jürgen Thym, “The True Principles for the

Practice of Harmony by Johann Philipp Kirnberger: a Translation,”

Journal of Music Theory 23:2 (1979), 171. The relation of

Schenker’s distinction to Kirnberger’s is noted by neither Rothgeb nor

Clark.

Return to text

35. Counterpoint, vol. 2, 215.

Return to text

36. Ibid., 216 (emphasis added).

Return to text

37. Counterpoint, vol. 1, xxx.

Return to text

38. Counterpoint, vol. 2, 216.

Return to text

39. Free Composition, 61, 64.

Return to text

40. “Heinrich Schenker on the Nature of the Seventh Chord,”

248–51.

Return to text

41. Ibid., 257 (emphasis added).

Return to text

42. Jean-Philippe Rameau, Treatise on Harmony, trans. by Philip

Gossett (New York: Dover, 1971), 27; see also 152–54.

Return to text

43. Carl Schachter, “Schenker’s Counterpoint,” The Musical Times

(October, 1988), 525.

Return to text

44. Counterpoint, vol. 1, xxv.

Return to text

45. Oswald Jonas, Introduction to the Theory of Heinrich Schenker,

trans. and ed. by John Rothgeb (New York: Longman, 1982), 52–61;

John Rothgeb, “Strict Counterpoint and Tonal Theory”; Carl Schachter,

“Schenker’s Counterpoint.”

Return to text

46. Counterpoint, vol. 2, xix.

Return to text

47. The idea is valuable not only in the context of “several passing

tones

<that> occur simultaneously.” The tenor’s half-note motion in Figure 2b,

for example, may be seen as a lower level, first-species counterpoint

to

the 7–6 suspension in the soprano (cf. also a 7–6 suspension

accompanied

by a 5–6 motion).

Return to text

48. “Schenker’s Counterpoint,” 529.

Return to text

49. “Strict Counterpoint and Tonal Theory,” 279, 280.

Return to text

50. Eytan Agmon, “Conventional Harmonic Wisdom and the Scope of

Schenkerian Theory: A Reply to John Rothgeb,” Music Theory Online

2.3 (1996). The relevant paragraphs are [16]–[18].

Return to text

51. I have also worked out a multi-leveled harmonic analysis of

Chopin’s

E-minor Prelude; to consider this analysis, however, would take us too

far afield, for the Prelude—unlike Mozart’s passage—is extremely

chromatic.

Return to text

52. See Eytan Agmon, “Functional Harmony Revisited: A

Prototype-Theoretic Approach,” Music Theory Spectrum 17:2 (1995),

206–208.

Return to text

53. In “Functional Harmony Revisited,” 208, the dominant potential of

II was seen as stronger in minor than in major, an idea that seems to

be

supported by the present example. Note, however, that since II has

dominant potential in major as well as minor, one is able to form, in

the

present case, a unified harmonic interpretation of two closely-related

passages that are nonetheless by no means identical.

Return to text

54. “Heinrich Schenker on the Nature of the Seventh Chord,” 222.

Return to text

55. See Eytan Agmon, “A Mathematical Model of the Diatonic System,”

Journal of Music Theory 33:1 (1989), 1–25; and idem,

“Coherent Tone-Systems: A Study in the Theory of Diatonicism,”

Journal of Music Theory 40:1 (1996), 39–59.

Return to text

56. Eytan Agmon, “Linear Transformations Between Cyclically

Generated Chord,” Musikometrika 3 (1991), 15–40.

Return to text

57. See “Linear Transformations,” 28, Definition 3 and Definition 5.

In “Functional Harmony Revisited,” n. 27, I have stated, misleadingly,

that the theory of linear transformations expresses “a dependency of

the

vertical dimension on the horizontal dimension

Return to text

Copyright Statement

Copyright © 1997 by the Society for Music Theory. All rights reserved.

[1] Copyrights for individual items published in Music Theory Online (MTO) are held by their authors. Items appearing in MTO may be saved and stored in electronic or paper form, and may be shared among individuals for purposes of scholarly research or discussion, but may not be republished in any form, electronic or print, without prior, written permission from the author(s), and advance notification of the editors of MTO.

[2] Any redistributed form of items published in MTO must include the following information in a form appropriate to the medium in which the items are to appear:

This item appeared in Music Theory Online in [VOLUME #, ISSUE #] on [DAY/MONTH/YEAR]. It was authored by [FULL NAME, EMAIL ADDRESS], with whose written permission it is reprinted here.

[3] Libraries may archive issues of MTO in electronic or paper form for public access so long as each issue is stored in its entirety, and no access fee is charged. Exceptions to these requirements must be approved in writing by the editors of MTO, who will act in accordance with the decisions of the Society for Music Theory.

This document and all portions thereof are protected by U.S. and international copyright laws. Material contained herein may be copied and/or distributed for research purposes only.

Prepared by Nicholas S. Blanchard and Tahirih Motazedian, Editorial Assistants