Fraught with Ought: An Outline of an Expressivist Meta‐Theory *

Parkhurst, Bryan J.

KEYWORDS: aesthetics, philosophy, language, analysis, ethics, metaethics

ABSTRACT: In this paper I develop a theory about language and musical analysis. My project is to defend a thesis about the meaning of the linguistic building blocks of musical analyses, which I call “analytical utterances.” The theory applies meta‐ethical expressivism to the domain of musical aesthetics. I try to understand analytical utterances as expressing attitudes of approval or endorsement, rather than as, in and of themselves, issuing statements of fact.

Copyright © 2013 Society for Music Theory

[1] Music theorists have been thinking for a while about the meaning, and meaningfulness, of the words people use to talk about music. Although Babbitt didn’t begin the trend,(1) the way he framed the problem—polemically, with conspicuous musical erudition, and with the same philosophical self‐assurance and sense of mission he found in the writings of neo‐pragmatists like Quine and logical empiricists like Hempel—seemed especially urgent during an era when music theory was seeking to establish itself as “a research discipline, the scope of which would encompass all music and whose natural home would therefore be the university” (Peles 2012, 23).

[2] Philosophy begins, one could impressionistically say, with Plato denying the rhapsodes admittance to an ideal polis on the grounds that their art is not “an undertaking that is serious or that has contact with the truth” (Plato 2004, 608a7–8). For its part, modern music theory begins similarly, with Babbitt excluding “unscientific”(2) musical discourse and its discussants from an ideal music department.(3) Although there are suggestive parallels between these inaugural exclusionary gestures, the analogy shouldn’t be carried too far: Babbitt, after all, was a not a Platonist but a committed positivist.(4) In several seminal articles from the 1960s he articulated a music‐theoretical program rooted in the Vienna Circle’s familiar demands for falsifiability and public verifiability of theoretical statements. This passage, from “Past and Present Concepts of the Nature and Limits of Music,” is representative:

[T]here is but one kind of language, one kind of method for the verbal formulation of “concepts” and the verbal analysis of such formulations: “scientific” language and “scientific” method.Writers on music routinely flout the meaningfulness maxim:. . . [O]ur concern is not whether music has been, is, can be, will be, or should be a “science,” whatever that may be assumed to mean, but simply that statements about music must conform to those verbal and methodological requirements which attend the possibility of meaningful discourse in any domain. (Babbitt 2003a, 78)

. . . [A]lthough there remain unsolved problems associated with the determination of these conditions for complex and sophisticated cases, no problems accompany the identification of the grossly “meaningless”; it is neither surprising nor singular that, casually and noncontroversially, a hypothetical, but cautiously unexaggerated instance of “musical criticism” is cited on the first page of an elementary discussion of language as “sheer nonsense” when “interpreted literally.” The content of this specific example is of no consequence, except to the extent that it shares with the majority of past and—admittedly—present “statements” about music the property of being at best an incorrigible statement of attitude grammatically disguised as a simple attributive assertion. If it is taken at its grammatical face value, then it creates inevitably a domain of discourse in which negation does not produce contradiction, and in which a pair of such assertions entails, in turn, any statement and its negation. (Babbitt 2003a, 78–79)(5)

[3] Babbitt’s prose is tortuous, but his point is straightforward: musical scholarship has hitherto permitted itself to speak nonsense, to trade in vacuities that can’t be subjected to (dis)confirmatory empirical tests. In “The Structure and Function of Music Theory” Babbitt singles out an offending sentence: “The historian [cannot], in the sanctified name of scholarship, be allowed such a verbal act as the following: ‘There can be no question that in many of Mendelssohn’s works there is missing that real depth that opens wide perspectives, the mysticism of the unutterable’” (Babbitt 2003b, 192). This “verbal act,” unattributed in Babbitt’s article, is from Lang’s Music in Western Civilization (1941, 811).(6) Like the logical positivists, who charged Hegelian metaphysical jargon with meaninglessness, Babbitt, following in their footsteps, targets the empty verbiage of music history written in an overtly critical mode.(7)

[4] The subsequent generation of music theorists chafed at Babbitt’s insistence on disciplining language. Unwilling to indiscriminately disown and demonize non‐literal or “incorrigible” music talk,(8) several thinkers (e.g., Guck [2006], Maus [1988], Cook [1992], Zbikowski [2008], to name some of the most prominent)(9) came to the defense of poetic, narrative, fictional, and especially metaphorical speech as applied to music. The usual maneuver of Babbitt’s opponents, if I may paint them with the same brush, is to argue that such loose talk is not so loose. They maintain, against Babbitt, that metaphors (et. al.) convey verifiable descriptions, and can thus figure in duly empirical musical inquiries. But at a deeper level they side with Babbitt: all parties to the debate agree that descriptive adequacy—the fitness of a linguistic item, or segment of language, for being used to assert facts—is a matter of cardinal importance.

[5] Guck’s work illustrates this fundamental harmony of opinion between Babbitt and his critics: “[T]he discursive clarity Babbitt required of musical discourse,” she says, “can be achieved with a wider variety of linguistic resources than he could have foreseen. In particular, ‘incorrigible statements’ can be rehabilitated using a method outlined in Babbitt’s statements about the evaluation of musical discourse. The musical analyses that result create the individuating accounts of music that he advocated, in part by opening analysis up to questions of expression” (Guck 2006, 58). The method of rehabilitation Guck proposes is not complicated: treat unverifiable critical statements, such as “the

[6] I sympathize with Guck’s animating concerns: Babbitt needs to be answered and the incorrigible needs to be rehabilitated. But I would like to find a way to do this that does not ask us to regard enrichingness and evocativeness as evidence for statements that prove to be enriching and evocative.

[7] Evidence is that which justifies (or goes toward the justification of) belief. That the sidewalk is wet justifies my belief in, and is thus evidence for, the proposition “it rained.” What justifies a belief in the proposition “I am auditorily appeared to by an unexpected‐seeming

[8] How, then, should we accommodate Guck’s important insight that things like enrichingness, convincingness, evocativeness, and the capacity to codify or change hearing are the kinds of standards against which music‐analytical statements are assessable?(11) I will spend the rest of the paper developing this insight by defending the thesis that the elemental statements of musical analyses, statements I call “analytical utterances,” are not best understood as descriptions (either of music or of one’s mental states), but instead as normative claims about how one ought to hear music.(12) Analytic utterances function to endorse systems of values according to which certain ways of perceiving music—or, more generically, appreciating or engaging with music—are better than others. By showing that surface grammar partially obscures the normativity of analytical utterances,(13) my arguments uncover the covert normativity (or “crypto‐normativity,” following Habermas 1987) of the music analyst’s dialect.

[9] The prefix “meta‐” appears in the title of this essay (with due apologies) because my claims are not primarily about pieces of music or about music itself, but about the language with which the exchange of music‐analytical judgments is transacted. Philosophers of ethics recognize a distinction in kind between substantive ethical investigations and metaethical ones. Roughly, the former have to do with what is good (or moral, or valuable, etc.), and the latter have to do with the nature of evaluative judgments and the terms or concepts that appear in them.(14) What follows is an attempt to raise and answer metaethical‐type questions about musical analysis.(15) I will have more to say shortly about what makes my meta‐theory an “expressivist” one.

Two Examples

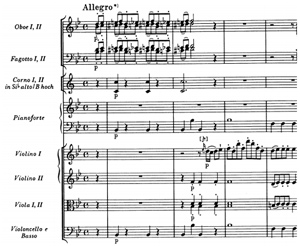

Example 1. Mozart, Piano Concerto in B-flat major, K. 450, measures 1–4

(click to enlarge)

Example 2. Haydn, Creation, “The Representation of Chaos,” measures 1–6

(click to enlarge)

[10] As a point of entry, let’s examine two paradigmatic analytical utterances. One is drawn from Tovey’s program notes and the other comes from Schenker’s Meisterwerk II.

Tovey, in his jaunty style, considers a passage from Mozart (Example 1):

The opening of thisB♭ concerto [Piano Concerto No. 15 inB♭ major, K. 450] shows Mozart in his most schalkhaft (or naughty) mood, and the change of accent. . . shows that his naughtiness is stimulated by his most dangerous wit.” (Tovey 1981, 31)

Schenker’s reading of the first few measures of “The Representation of Chaos” from Haydn’s Creation (Example 2), uses a specialist’s vocabulary, and, in contrast to Tovey’s analysis, isn’t easy to comprehend unless you follow along with the score (or know it by heart):

Bar 4 TheE♭ 2 due in bar 4 is delayed until bar 5, giving the impression of a spent force; g2 signifies an ornamentation of the resolution . . . and the crotchetsA♭ 2 – g2, while pointing to a higher register, also echo, in rhythmic diminution, the original syncopated motiveA♭ 1 – g1. (Schenker 1996, 97–98)

[11] In saying such things, are Schenker and Tovey engaged in describing music? Plainly enough, the answer to this question hinges on what the operative notion of description is. The music theory literature, confusingly, sometimes treats “description” as a synonym of “mere description.” This began with Edward Cone’s (1960, 173) derogation of what he calls “pure description” in scholarly writing about music, a criticism echoed influentially by Kerman (1985), who called for a return to a self‐consciously evaluative, rather than descriptive, mode of criticism in the field of musicology. In “Analysis Today,” Cone equates description with the rote drudgery of “simply assigning names or numbers” to notes or collections of notes (173). Description, for Cone, contrasts with the more contemplative and humane “analytical act” of “discovering and explaining relationships” with a view to uncovering “insights [that] reveal how a piece of music should be heard, which in turn implies how it should be played” (173–74). Whereas description is the mechanical transformation of one kind of data into another kind of data, and is uninformative because non‐interpretive, musical analysis yields “a discovery, or at least a preliminary hypothesis to be tested by its fruitfulness in leading to further discovery” (173).

[12] With respect to our paradigmatic examples, (1) it is unlikely that Cone would charge Tovey’s or Schenker’s words with being “descriptions” (he singles out Schenker’s analyses for commendation in the article); and (2) what we need to settle is not whether their words are “descriptive” in Cone’s pejorative sense, but instead whether they are descriptive in the sense of purporting to represent how the world is. Do they aim at truth? Is their principal function to indicate the speaker’s belief, and to bring about the belief in others, that the music under examination bears certain properties and lacks certain other properties?

[13] One way to motivate the view that “the opening

[14] Another motivation is the thought that when we disagree with a speaker’s sincere assertion, we must think that she is either mistaken about the relevant facts or misunderstands the meanings of the words she uses. If you say “the cat is on the mat” and I dispute what you say, I can explain your error as arising from your failure to observe that the cat moved, or as arising from your mistaken belief that “mat” means what “hat” means. Now consider Schenker’s statement that “the

[15] In order to weaken the conviction that Tovey and Schenker are in the business of asserting truths we might also look at how well utterances like theirs comport with reputable theories of assertion. Here is a definition of assertion derived from the criteria set out famously in Grice 1957:

S asserts that p by the utterance u if and only if there is a hearer H such that:

(i) S intends u to produce in H the belief that p

(ii) S intends H to recognize that (i)

(iii) S intends H to believe that p for the reason that (i)

Accordingly, I assert to you that there is a cat on the mat by saying “there is a cat on the mat” if and only if I intend for you to believe that there is a cat on the mat, and if and only if I also intend for you to be aware of this first intention and to treat it as your reason for believing there is a cat on the mat.

[16] (i) could well be false of Tovey’s statement—in which case (ii) and (iii) would be false as well—without at all undermining its status as an analytical utterance. Clearly, though, if it can be a serviceable analytical utterance while failing to meet the criteria for assertionhood, then analytical utterances are not a species of assertion, or at least not a species of Gricean assertion. What Tovey intends to produce in us, we may well think, is not a belief. We can imagine him being perfectly indifferent to belief formation, or having no clear idea of what precisely one would come to believe (if anything at all) in accepting his utterance, which would falsify (i). What Tovey intends, instead, is that we (try to) undergo an auditory experience of a certain sort. Analytical utterances, I therefore suggest, have as their essential objective getting us to do something—to use our bodies and minds in a particular way so as to be conscious of music in a particular way—rather than merely getting us, as is sometimes said in epistemology, to place this or that proposition in the mind’s “belief box.”

[17] Those familiar with this area of ethics will know that I have just opened up a big can of worms. There is a vast literature in value theory about whether aesthetic or ethical evaluations are made true by the way the world is (realism), or instead do something other than making matter‐of‐factual claims, such as commending or disapproving, or committing oneself to some course of action, or placing oneself or others under obligations (anti‐realism). Many of these arguments could be made, mutatis mutandis, about analytical utterances. But there is no room in this paper to get caught up in rehashing or repurposing that debate. For the time being, I will simply reiterate the intuition that will orient my positive account of analytical utterances: analytical utterances are meant to engender action and experience, not belief. Expressivism, I hope to show, is an elegant way of accommodating this intuition.(17)

THE EXPRESSIVIST ANALYSIS

[18] Ethical expressivism is a theory that adopts an oblique strategy for analyzing evaluative terms: the ethical expressivist takes as her starting point the state of mind a moral judge is in when she sincerely renders a moral judgment. The expressivist might give an account of the meaning of “murder is wrong” in terms of the expression of an attitude (as opposed to the assertion of a proposition) by making these claims: (1) Saying “murder is wrong” is the same as saying “It is rational for the perpetrator of a murder to feel guilty, and for others to feel moral outrage toward the murder.” (2) Saying “it is rational to X” is (nothing more than) expressing an attitude of acceptance on the part of the speaker toward the norms that prescribe doing X. Thus (3) to say “murder is wrong” is to express one’s acceptance of the norms that prescribe feelings of guilt for the murderer and feelings of outrage for everyone else.(18)

[19] Taking a cue from the tenets of expressivism, we can try to explicate the meaning of analytical utterances by stating what psychological attitude they serve to express. The expressivist formula I favor looks like this: In music‐analytical contexts, to say “x is (an) f ” is to voice one’s commitment to a set of norms that makes it correct to hear x as (an) f. Broadly speaking, this is an imperatival analysis. The sentence “it is correct to hear x as (an) f ” is a norm which we might equally well capture with the prescriptive notation, ¡hear x as an f !(19)

[20] I will not attempt to give a thoroughgoing analysis of the concept of hearing‐as.(20) Sketchily, hearing A as B is hearing A in terms of B, or under the guise of B, where that means something close to using one’s concept of B as a way of organizing the auditory impressions afforded by A. I have an expansive view of what can count as hearing‐as: one can hear pitches as pitch class sets (i.e., hear multiplicities as unities), hear pitch class sets as dominant chords, hear dominant chords as half‐cadential pauses, hear half‐cadential pauses as moments of structural articulation, hear moments of structural articulation as hypermetrically marked, and so on. Exercises of one’s power to hear‐as are, to a close degree of approximation, the “apperceptions” that Lewin dwells on in “Music Theory, Phenomenology, and Modes of Perception”:

I am asserting inter alia that formal musical perceptions are what are sometimes called “apperceptions,” since each one embodies “the process of understanding by which newly observed qualities of an object are related to past experience.” The model goes even farther in asserting a specifically linguistic component, in a broad sense, for the way in which past experience is actively brought to bear on observation. Our sense of the past, in making perception statements, is thereby necessarily involved with socio‐cultural forces that shaped the language. . . and our acquisition of that language. In particular, to the extent that the language. . . involves the language of any music theory, that means we must be ready to consider the context. . . for perception. . . as having a theoretical component, along with whatever psychoacoustic component it may possess.” (Lewin 1986, 342)

[21] For Lewin, musical perception is irreducibly concept laden (a point Kant made about all types of experience, as did the phenomenologists through whom Lewin receives this Kantian inheritance)(21) in that musical perception takes place within the framework of a pre‐existing conceptual or theoretical scheme, one conditioned to a large degree by language and culture. My views can be situated alongside Lewin’s: I attempt to understand analytical utterances as, at bottom, a way of using language to endorse a conceptual scheme and its attendant ways of hearing. To that end, I posit these equivalences: The sentence “x is (an) f ” (offered as an analytical utterance) = an endorsement of norms that make it correct to hear x as (an) f = an endorsement of norms that, together with some facts, entail the imperative ¡hear x as (an) f !

[22] For an illustration of this point, consider the following argument:

THE APPRECIATIVE ARGUMENT(1a) Hearing musical event x as (an) f results in the hearer’s appreciating x more.

(2a) x is such that it is correct, other things being equal, to take measures to appreciate x as much as possible.

(3a) Therefore it is correct, other things being equal, to hear x as (an) f.

(1a) is a factual claim. Call it a “background fact.” (2a) is value judgment. Call it a “background norm.” Together these comprise the “background.” (3a) is also a value judgment. It is a conclusion from (1a) and (2a). Call it the “foreground norm.”

With this terminology at our disposal, we can recast the foregoing analysis this way: offering “x is (an) f ” as an analytical utterance is the same as endorsing some background norm or norms, which, taken together with some accepted background fact or facts, implies the foreground norm. More succinctly: the background entails the foreground, and the foreground expresses acceptance of the background.

One and the same foreground norm may express commitment to differing backgrounds. The following arguments have the same foregrounds as the Appreciative Argument but different backgrounds:

THE COMPOSER’S INTENT ARGUMENT(22)(1b) To hear some musical event x as (an) f is to hear x as x’s composer intended.

(2b) x is such that it is correct, other things being equal, to hear x as its composer intended

(3b) Therefore it is correct, other things being equal, to hear x as (an) f.

THE HISTORICAL RECEPTION ARGUMENT

(1c) To hear some musical event x as (an) f is to hear x as x’s original audience heard it.

(2c) x is such that it is correct, other things being equal, to hear x as its original audience heard it.

(3c) Therefore it is correct, other things being equal, to hear x as (an) f.

[23] These examples are contrived and oversimple. Really, offering an analytical utterance means accepting a host of background norms and background facts.(23) An analytical utterance, as I conceive of it, is the tip of a normative and factual iceberg. The application of, say, a Schenkerian analytical label such as “prolongation” or “interruption” may carry with it an endorsement of a comprehensive Schenkerian ethos, and also the acceptance of an extensive fact set.(24)

[24] Expressivism about analytical utterances accords with Cone’s recognition that the special undertaking of the music analyst is to “reveal how a piece of music should be heard” (Cone 1960, 174). Saying that a piece should be heard in one way rather than another is to prescribe hearing it in one way rather than another. Curiously, Cone disparages “prescription” in music analysis, and identifies it with illicit “insistence upon the validity of relationships not supported by the text” (174). He finds the tendentious distortion of “prescription” to be “obvious in the absurd irrelevancies of Werker's analyses of Bach but

CHALLENGES

[25] The expressivist proposal faces three immediate challenges. I raise and address each one in turn.

[26] Challenge #1: Jonathan Kramer enunciates this aspiration: “In an unabashedly eclectic manner, I want to use whatever tools and whatever assumptions can enrich my musical experiences. And I want to share my enriched experiences with other listeners, through my sometimes formalist analyses—not to convince them how they ought to understand the music, but to suggest ways of hearing that may become uniquely their own” (Kramer 2004, 370). I find there to be something both true and beautiful in Kramer’s sentiment. But he is, for all intents and purposes, asserting the negation of the expressivist theory.

[27] The worry may have to do with the implicit universalistic force of a bare imperative. ¡Hear x as (an) f !, as candidate for what the analytical utterance “x is (an) f ” means, seems too strong, too standpoint‐insensitive, for the job. Analytical utterances aren’t Kant’s Categorical Imperative, binding on all rational agents: we would like to know about restrictions on who should comply, and why, and under what circumstances. One may argue that such information belongs in an account of the pragmatics of such utterances, but the fact remains that without supplementation (of this sort) or qualification (of another sort), the theory as it stands is deficient.

[28] Answer #1: “Prescription” doesn’t need to have a sinister air to it. Invitations, advice, recipes, suggestions, and friendly recommendations all have prescriptive force. “Ought” can be similarly innocuous (“you ought to come out for a drink with me tonight!”). Thus Kramer’s “convinc[ing] [listeners] how they ought to understand the music” is compatible with his “suggest[ing] ways of hearing that may become uniquely their own.”

[29] This is not to say that we can rest easy. The addressees of a music analysis should be attuned to the institutional and disciplinary forms of power and coercion (both hidden and overt) that the analysis may serve to exercise or extend. We should be on the lookout for, and endeavor to unearth, forms of ideological control or domination encoded in analytical utterances that have gone unrecognized both by the analyst herself and by her audience. More broadly, given that analytical utterances in effect urge us to act in a certain way, and to partake of a shared value system, we need to figure out whether the causes to which we are being recruited are worthy ones.(26) Note, though, that it isn’t prescriptions per se that are worrisome. It is what is prescribed, why it is prescribed, how it is prescribed, what enables it to be prescribed, who is allowed to prescribe it, and so forth, that should give us pause. To think otherwise is to fail to recognize that content (implicit or explicit), and not form (implicit or explicit), must be the basis for ethically or politically critiquing a speech act.

[30] Further—in response to the concern about universality—the bare imperative ¡hear x as (an) f ! does not give the meaning of the analytical utterance “x is (an) f.” Rather, offering “x is (an) f ” as an analytical utterance means expressing one’s commitment to a background that entails ¡hear x as (an) f !. Contextual information about who should accept the analytical utterance, and why, and under what circumstances, is information that is encoded in the factual and normative background. The background, we can say, articulates a reason for accepting the analytical utterance. Thus the prescriptive force of an analytical utterance is not universalistic or standpoint insensitive, and the expressivist analysis permits us to find a home, in our theory, for all the important contextual information.

[31] Challenge #2: The following look like analytic truths (statements true in virtue of the meanings of their terms):

“A major is the tonic triad if and only if E major is the dominant triad”

“A major is the tonic triad if and only if A is the first scale degree,C♯ is the third scale degree, and E is the fifth scale degree”

According to the expressivist reading, “A major is the tonic triad” is an expression of one’s endorsement of norms that make it correct to hear A major as the tonic triad. But it isn’t clear that this endorsement entails and is entailed by an endorsement of norms that make it correct to hear E major as the dominant triad. Arguably, someone could coherently endorse the former without endorsing the latter, and vice versa. If the endorsements don’t entail each other, the statements that express the endorsements (the stuff on either side of the “if and only if” connector) shouldn’t either. But by all appearances the statements do entail each other. This implies that the statements are not endorsements, as I claim they are.

[32] Answer #2: There is a tidy expressivist solution to this. In claiming that A major is the tonic triad, the expressivist can say, one is endorsing a system of norms and accepting a set of background facts that together entail that it is correct to hear A major as the tonic triad. The system of norms endorsed in such cases is Roman Numeral Analysis.

[33] We can construe RNA as an activity regulated by a system of rules of the form “It is correct to hear X as Y in context C.” For RNA, X is a pitch class set, Y is a Stufe,(27) and C is some (perhaps quite complicated and disjunctive) set of brute acoustical facts.(28) It is an essential feature of the RNA rule‐system, part of what makes it the rule‐system it is, that the very same context that makes it correct to hear [A,

[34] Challenge #3: Some analytical utterances don’t look like they call for expressivist treatment. Isn’t the claim that this or that chord is a dominant chord a claim made true or false by observer‐independent facts? It seems one could prove such a claim to be true simply by means of the relevant acoustical information—frequency ratios and suchlike. Why, then, if a predicate like “dominant” is so fit for describing the world, is there any incentive to go down the expressivist path when dealing with utterances that contain it?

[35] Answer #3: This isn’t really a problem, given the way I have reconnoitered the conceptual terrain. I concede the point about descriptivity. It will be obvious by now that descriptive content, world‐representing mental states, and assertion play an important role in the way I “expressivize” analytical utterances. How? I’ve held that in offering an analytic utterance, a music analyst commits herself to the truth of some set of background facts. Often it will be obvious what those are, and so the analytic utterance can function to communicate (or assert, if you like) those very facts. I concede, for this reason, that many or most analytical utterances carry descriptive freight of varying degrees of richness and precision.(29) I also suggested that there are necessary and sufficient naturalistic (acoustical) conditions for the correct application of a RNA label to a pitch class set. That’s just about as descriptive as a predicate can get. When I correctly apply a RNA label, I thereby describe the world as being such that an acoustical state of affairs obtains. And I suspect we could succeed in finding naturalistic necessary and sufficient conditions for correct labeling in other basic kinds of music analysis—non‐chord tone classification in harmonically‐supported contexts, simple foreground Schenkerian reductions, and whatnot.

The attraction of handling these kinds of analytical utterances expressivistically is theoretical unity. The expressivist theory is consistent with the claim that some analytical utterances have truth conditions (and it is no part of any expressivist theory to claim that language that is not exclusively descriptive is exclusively non‐descriptive), and it allows us to tell a single story about our music‐analytical linguistic practice. It is a virtue of the theory that it indicates what is common to a range of analytical activities, everything from low‐level taxonomizing—tasks, as Cone says, “involving no musical discrimination whatsoever”—to verbally transmitting the musical epiphanies through which a work can be “revealed as an organic temporal unity

Furthermore, while it may be the case that the analytical utterances governed by RNA have truth conditions, nevertheless the issue of whether RNA is a good analytical tool to bring to bear on a piece of music is not a factual matter. This turns out to be a normative question about whether or not employing RNA is useful or beneficial. A dispute about whether something is a dominant chord—which, from a perspective internal to the framework of RNA, is a dispute about a matter of fact—may at other times be a non‐factual dispute about whether employing RNA is a worthwhile thing to do.(30)

One could object that it is equally the case that the question of whether something is phlogiston may be construed as a question about whether it is worthwhile to accept phlogiston theory or not, and that the same goes for other scientific predicates and the theories they are embedded in.(31) This would render the expressivist analysis applicable to an eminently descriptive domain of language—physical science—a result that would trivialize expressivism by universalizing it. This takes us into the deep, dark waters of the debate surrounding scientific instrumentalism and anti‐realism, where I’m likely to find myself in over my head. But I can at least note that the question of whether phlogiston theory is correct, or gets the facts straight, is a question that—pre‐theoretically, anyway—sounds sensible to ask. The question of whether RNA itself (rather than a particular act of chord labeling) is correct, or gets the facts straight seems, by contrast, to commit a category error. The strong intuition (though it is contestable) is that scientific theories answer to the way the world is, whereas music analyses answer to what we see fit to do with or to music. We must choose, based on what we value, how we shall imaginatively, sensuously, and corporeally engage with music. Analytical utterances, I hold, guide and coordinate this engagement within communities of appreciators by expressing commitment to norms of hearing.

Parkhurst, Bryan J.

University of Michigan

Department of Music Theory

Department of Philosophy

2215 Angell Hall

435 South State Street

Ann Arbor, MI 48109

brypark@umich.edu

Works Cited

Ayer, A.J. 1946. Language, Truth, and Logic. London: Victor Gollanz.

Babbitt, Milton. 2003a. “Past and Present Concepts of the Nature and Limits of Music.” In The Collected Essays of Milton Babbitt, ed. Stephen Peles, 78–85. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

—————. 2003b. “The Structure and Function of Music Theory.” In The Collected Essays of Milton Babbitt, ed. Stephen Peles, 191–201. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

—————. 1965. “The Structure and Function of Music Theory.” College Music Symposium 5: 49–60.

Bent, Ian. 1987. Analysis. Macmillan Press.

Bradley, F.H. 1930. Appearance and Reality. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Budd, Malcolm. 1987. “Wittgenstein on Seeing Aspects.” Mind 96, no. 381: 1–17.

Cone, Edward T. 1960. “Analysis Today.” The Musical Quarterly 46, no. 2: 172–88.

Cook, Nicholas. 1992. Music, Imagination, and Culture. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Chisholm, Roderick. 1976. Person and Object: A Metaphysical Study. London: G. Allen and Unwin.

Davidson, Donald. 1978. “What Metaphors Mean.” Critical Inquiry 5, no. 1: 31–47.

Gibbard, Alan. 1990. Wise Choices, Apt Feelings. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Grice, H.P. 1957. “Meaning.” The Philosophical Review 66: 377–88.

Guck, Marion. 2006. “Rehabilitating the Incorrigible.” In Theory, Analysis, and Meaning in Music, ed. Anthony Pople, 57–66. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Habermas, Jürgen. 1987. The Philosophical Discourse of Modernity. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Hare, R.M. 1972. The Language of Morals. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Kane, Brian. 2011. “Excavating Lewin’s Phenomenology.” Music Theory Spectrum 33, no. 1: 27–36.

Kerman, Joseph. 1985. Contemplating Music. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Korsyn, Kevin. 2003. Decentering Music. New York: Oxford University Press.

Kramer, Jonathan. 2004. “The Concept of Disunity in Musical Analysis.” Music Analysis 23, nos. 2–3: 361–72.

Lang, Paul Henry. 1941. Music in Western Civilization. New York: Norton.

Lewin, David. 1969. “Behind the Beyond.” Perspective of New Music 7, no. 2: 59–69.

—————. 1986. “Music Theory, Phenomenology, and Modes of Perception.” Music Perception 3, no. 4: 327–92.

Maus, Fred E. 1988. “Music as Drama.” Music Theory Spectrum 10: 56–73.

Meyer, Leonard. 1961. Emotion and Meaning in Music. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Peles, Stephen. 2012. “‘Any Theory is a Choice’: Babbitt and the Post‐War Reinvention of Music Theory.” Music Theory Spectrum 34, no. 1: 22–24.

Plato. 2004. Republic, translated by C.D.C. Reeve. Indianapolis: Hackett.

Rorty, Richard. 1982. Consequences of Pragmatism: Essays, 1972–1980. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota.

Schenker, Heinrich. (1926) 1996. The Masterwork in Music, A Yearbook, Volume 2, ed. William Drabkin. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Tovey, Donald Francis. (1935‐9) 1981. Essays in Musical Analysis Vol. II. London: Oxford University Press.

Wittgenstein, Ludwig. 1953. Philosophical Investigations. London: Basil Blackwell.

—————. 1989. Wittgenstein's Lectures on the Foundations of Mathematics, Cambridge, 1939: From the Notes of R.G. Bosanquet, Norman Malcolm, Rush Rhees and Yorick Smythies. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Zbikowski, Lawrence. 2008. “Metaphor and Music.” In The Cambridge Handbook of Metaphor and Thought, ed. Raymond W. Gibbs Jr., 502–24. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Footnotes

* I would like to thank several people for providing helpful comments on earlier drafts of this paper: Kendall Walton, Ramon Satyendra, Kevin Korsyn, Patricia Hall, Sarah Buss, Peter Railton, Marion Guck, Joseph Dubiel, Nils Stear, Allan Gibbard, James Harold, Jennifer Judkins, Stephan Hammel, and Ryan Stickney. I’ve also talked at length with Daniel Drucker, Dmitri Gallow, and Ben Laude about many of these ideas. I gave shorter versions of the paper at Music Theory Midwest (Ann Arbor, Summer 2012) and the Annual Meeting of the American Society for Aesthetics (St. Louis, Fall 2012), and received useful suggestions and challenges at both those events. I didn’t come up with the rhyme “fraught with ought.” It appears in Wilfrid Sellars’s writings.

Return to text

1. It goes back at least as far as the nineteenth century. The idea that music is ineffable, a commonplace among the philosophers associated with German Romanticism, is just as much a linguistic thesis about the semantic poverty of descriptions of music as it is a thesis about the intrinsically non‐conceptual nature of music itself.

Return to text

2. The upcoming quotation clarifies Babbitt’s understanding of what makes language scientific: its fitness, owing to its meaningfulness, for incorporation into a scientific theory (whether or not it is so used).

Return to text

3. “The composer who insists that he is concerned only with writing music and not with talking about it may once have been, may still be, a commendable—even enviable—figure, but once he presumes to speak or take pen in hand in order to describe, inform, evaluate, reward, or teach, he cannot presume to claim exemption—on medical or vocational grounds—from the requirements of cognitive communication. Nor can the performer, that traditionally most pristine of non‐intellectuals, be permitted his easy evaluatives which determine in turn what music is permitted to be heard, on the plea of ignorance of the requirements of responsible normative discourse” (Babbitt 2003b, 192).

Return to text

4. However, for reflections on the shared (and flawed) presuppositions of Platonism and positivism, see Rorty 1982.

Return to text

5. Here Babbitt has in mind the principle of explosion, which allows one to derive any arbitrary proposition from a contradiction:

P1. Q & ∼Q

P2. Q (from P1)

P3. ∼Q (from P1)

P4. Q v R (from P2)

C. R (from P3 and P4)

What Babbitt means by “negation not producing contradiction” is that if one person utters a “statement of attitude,” such as “I like chocolate,” and another person utters the formal contradiction of that statement, “it is not the case that I like chocolate,” the two speakers have not thereby contradicted each other (because the referent of indexical “I” depends on who says it). But if their attitudinal utterances are couched as “simple attributive assertions” (e.g., “chocolate is good” and “it is not the case that chocolate is good”), then, if we take the grammatical form of the utterances to accurately indicate their logical form, yet still insist that both speakers have spoken the truth, we will thereby countenance believing a contradiction (by building a conjunction out of the speakers’ respective truths: “it is the case that chocolate is good and it is not the case that chocolate is good”), and thus fall prey to the principle of explosion. See note 9 for more on incorrigibility.

Return to text

6. Neither Babbitt’s original article (Babbitt 1965) nor Peles’s edition (Babbitt 2003b) mentions the provenance of the quote about Mendelssohn..

Return to text

7. A.J. Ayer’s preferred nonsense sentence was “the Absolute enters into, but is itself incapable of, evolution and progress” (Ayer 1946, 36). The quote is from the British idealist and post‐Hegelian F.H. Bradley (1930, 442). It is interesting, and probably non‐coincidental, that the inception of both Anglophone analytic philosophy (initiated by Russell and Moore’s repudiation of idealism) and American academic music theory happens as a recoil from the putative meaninglessness (as opposed to the putative incorrectness) of an earlier tradition.

Return to text

8. “But the problems of our time certainly cannot be expressed in or discussed in what has passed generally for the language of musical discourse, that language in which the incorrigible personal statement is granted the grammatical form of an attributive proposition, and in which negation—therefore—does not produce a contradiction; that wonderful language which permits anything to be said and virtually nothing to be communicated” (Babbitt 2003b, 192). As far as I know, nobody has yet pointed out that Babbitt’s criticism of incorrigibility is off the mark. Incorrigible statements may yield a contradiction when conjoined with their negations. “A portion of Milton Babbitt’s visual field appears red,” when uttered by Milton Babbitt, is incorrigible (immune to error, transparently true), and has the grammatical form of an attributive proposition, but “a portion of Milton Babbitt’s visual field appears red and it is not the case that a portion of Milton Babbitt’s visual field appears red” is a contradiction (no matter who says it). It is clear from context that Babbitt does not reject incorrigible phenomenological testimony per se—indeed, all meaningful statements, for the positivists whom Babbitt emulates, are translatable into complex statements about one’s own sense data, and it is the very incorrigibility of these statements that allows them to supply the bedrock of the positivist’s foundationalist epistemology. Babbitt’s grievance, in spite of what he says, is not against incorrigibility itself, but against those linguistic forms that amount to externalizations of emotion or affect, but masquerade as assertions that correspond to facts about the (extra‐subjective) world (e.g., “I like chocolate” masquerading as “chocolate is good”). This is a standard positivist complaint about value judgments and aesthetic judgments.

Return to text

9. For a list of publications on music and metaphor see the bibliography of Zbikowski 2008.

Return to text

10. Chisholm (1976, 49–50) suggests that “I am appeared to redly” is the proper interpretation of “I am aware of a red appearance,” since the former sentence, unlike the latter, does not commit one to the existence of spooky, non‐empirical entities such as appearances.

Return to text

11. I am in broad agreement with nearly everything else Guck says in ‘Rehabilitating the Incorrigible.’ My subsequent arguments should be read as friendly amendments to her position, and are offered in a spirit of basic solidarity.

Return to text

12. “Normative,” in its philosophical usage, does not mean “statistically likely,” as it sometimes does in its music‐theoretical usage. See, for example, Meyer’s discussion of stylistic “norms” in Meyer 1961. If descriptions are what fall on the “is” side of Hume’s “is/ought” distinction, norms (as philosophers think of them) are what fall on the “ought” side. A normative concept is a concept of what one should do, where the should is not predictive. Such a concept needn’t be moral. There are epistemic norms, prudential norms, grammatical norms, and plenty of other varieties.

Return to text

13. I’m grateful to an anonymous reviewer for pressing me to distill this thesis down to its basic parts, and for noting that the evaluative force of analytical utterances is conveyed surreptitiously, since they don’t wear their value‐judgmental character on their sleeves. I don’t think that there is anything inherently insidious about this obscurity, but it can be dangerous for a variety of reasons to fail to understand that a normative judgment is a normative judgment.

Return to text

14. Normative ethicists would argue about whether euthanasia is morally permissible, whereas metaethicists would argue about whether the sentence “euthanasia is morally permissible” is a statement of fact, or an advertisement of one’s tastes, or something else, and also about whether and how such a claim is intrinsically action‐guiding, and about other issues surrounding its epistemological, metaphysical, semantic, and psychological status.

Return to text

15. One anonymous reviewer was concerned—rightly, I think, given the insensitivity and occasional hostility toward historical contextualizing that sometimes mars the work of analytic philosophers—about whether it is my ambition to make a universal and ahistorical claim about language. I have no pretensions of universality: I am interested in one quite parochial way of talking and the fairly narrow context in which it transpires. I also acknowledge that it is a matter of historical contingency that this way of talking arose in the first place. I would like to develop a more refined view about the historical (and institutional, and ideological, and disciplinary, etc.) factors that gave rise to such a discursive practice. For now, I am content to work through my curiosity about the nuts and bolts of how this domain of language works by making precise how it may be seen to issue prescriptions rather than descriptions. With an account like mine in hand, we are well positioned to begin (or to continue) pursuing the significant historical questions. My work could be read as an auxiliary to Korsyn’s incisive explanations of how music scholarship embodies a contest among “interest groups that compete for the cultural authority to speak about music” (Korsyn 2003, 6). It makes sense that such a contest would involve the use of (surreptitiously) evaluative and prescriptive language.

Return to text

16. Or, if you prefer, that some proposition is true. For our purposes the difference doesn’t matter.

Return to text

17. I don’t wish to give the false appearance that the “intuition pumps” I introduced above can only be dealt with by means of expressivism. Expressivism is sufficient, but not necessary, for accommodating them.

Return to text

18. My understanding of metaethical expressivism comes primarily from (1) conversations with Allan Gibbard, (2) discussions that took place in his seminar on ethics at the University of Michigan during the winter semester of 2011, and (3) Gibbard 1990.

Return to text

19. I borrow this prescription notation from Hare 1972.

Return to text

20. The notion of seeing‐as is prominent in the thought of the later Wittgenstein. Malcolm Budd has argued that Wittgensteinian “aspect switches”—what happens when one toggles back and forth between seeing the duck‐rabbit figure (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Duck‐Rabbit_illusion.jpg) now as a duck picture, now as a rabbit picture—are to be explained as “a change in the interpretation in accordance with which we see something” (Budd 1987, 17). Wittgenstein is fond of using musical examples to illustrate aspect switches. For example: “I say: ‘I can think of this face (which gives an impression of timidity) as courageous too.’

Return to text

21. Kane (2011) identifies the phenomenologists who impacted Lewin’s thinking.

Return to text

22. These arguments indicate that I conceive of analysis less narrowly than does Ian Bent in Analysis (1987, 4–5). He thinks that “the primary impulse of analysis is an empirical one: to get to grips with something on its own terms rather than in terms of other things.” This being the case, “its starting‐point is a phenomenon itself as [analysis] does not necessarily rely on external factors (such as biographical facts, political events, social conditions, educational methods, and all the other elements that make up the environment of that phenomenon).” Bent’s position is at odds with my position, since I’m happy to say that a statement that endorses hearing music “in terms of other things” counts as an analytical utterance, just in virtue of endorsing hearing it in any way at all. Bent’s position is also at odds with itself: he goes on to say that “analysis is the means of answering directly the question ‘How does it work?’” and that “[i]ts central activity is comparison,” by means of which “it determines the structural elements [of a piece] and discovers the functions of those elements.” But notice: to understand A by comparing it with B—Bent uses the example of comparing “the work and an abstract ‘model’ such as sonata form or a recognized style”—is a case, if anything is, of “getting to grips” with A in terms of other (non‐A) things rather than on A’s “own terms.” A further point of conflict is that I don’t believe pieces of music have “their own terms,” and I also see no reason why political events, social conditions, et. al., couldn’t provide the needed bases for comparison, if indeed analysis requires comparison.

Return to text

23. Breaking things down into a foreground and background may help us to differentiate music theory from music analysis. The set of background facts and background norms is what we might wish to identify with a theory of music; the foreground norms are what are what are presented in and through musical analyses. The theory/analysis dichotomy is a difficult topic that I cannot adequately tackle here, so I leave this as an inkling that could prompt future lines of inquiry. It is worth comparing this suggestion with the way Lewin (1969) carves up theory and analysis. According to Lewin, one theorizes about a “sound‐universe,” which represents a “general mode of hearing” (1969, 62) or, equivalently, “the ways in which

Return to text

24. As a parallel, think of a magistrate pronouncing a defendant guilty. In doing so, she signals her endorsement of the extensive legal code, and also a wide body of accepted facts, relative to which it is correct to regard the defendant as guilty.

Return to text

25. The term Cone successfully defines is not “prescription” but “eisigesis”: the act of misinterpreting a text by projecting onto it one’s own irrelevant ideas and prejudices.

Return to text

26. I don’t mean to suggest that it comes down to a simple binary choice between worthy and unworthy. It may be that any analytical utterance—embedded as it is in an academic discourse supported by various cultural institutions that play an identifiable role in maintaining the economic and political status quo—inevitably leaves a trail, so to speak, that leads to something that should be critiqued or resisted. Whether or not this is so, my basic point still holds: that an utterance is prescriptive is not, in and of itself, grounds for criticizing the utterance.

Return to text

27. Or chord function. It is immaterial, for present concerns, what notional entity a Roman numeral designates.

Return to text

28. I make the simplifying assumption here that RNA is fully determinate and contains no ambiguities about which functional aspects get assigned to which pitch class sets in which contexts. I also assume that brute acoustical facts settle the question of what key a passage is in, which is debatable.

Return to text

29. It may be that the majority of analytical utterances are descriptive in that they place descriptive boundaries on the musical objects to which they pertain. If I call a musical moment “bombastic,” not only am I endorsing norms that make it correct to hear it as bombastic; I am also ruling out the state of affairs that the piece is uniformly one decibel in volume. It is necessary for the correct application of “bombastic” that the piece not be that way. Frenetic pieces, we can agree, don’t consist of a single chord held for three years (I am thinking of John Cage’s piece Organ2/ASLSP As SLow aS Possible); the closure of a Schenkerian Ursatz cannot be supported harmonically by Scriabin’s Prometheus chord, and so forth. Even the most minimally descriptive analytical utterances will often tell us quite a bit about how a piece isn’t, even if they don’t enable us to construct a detailed auditory image of how it is.

Return to text

30. Indeed this is precisely the sort of parting of ways we can witness between Schoenberg, who favored an over‐particular approach where virtually every triadic simultaneity receives some Roman Numeral label, and Schenker, for whom many triadic simultaneities weren’t fit for a Roman Numeral label.

Return to text

31. Phlogiston was formerly thought to be the substance that flames are made of.

Return to text

P1. Q & ∼Q

P2. Q (from P1)

P3. ∼Q (from P1)

P4. Q v R (from P2)

C. R (from P3 and P4)

What Babbitt means by “negation not producing contradiction” is that if one person utters a “statement of attitude,” such as “I like chocolate,” and another person utters the formal contradiction of that statement, “it is not the case that I like chocolate,” the two speakers have not thereby contradicted each other (because the referent of indexical “I” depends on who says it). But if their attitudinal utterances are couched as “simple attributive assertions” (e.g., “chocolate is good” and “it is not the case that chocolate is good”), then, if we take the grammatical form of the utterances to accurately indicate their logical form, yet still insist that both speakers have spoken the truth, we will thereby countenance believing a contradiction (by building a conjunction out of the speakers’ respective truths: “it is the case that chocolate is good and it is not the case that chocolate is good”), and thus fall prey to the principle of explosion. See note 9 for more on incorrigibility.

Copyright Statement

Copyright © 2013 by the Society for Music Theory. All rights reserved.

[1] Copyrights for individual items published in Music Theory Online (MTO) are held by their authors. Items appearing in MTO may be saved and stored in electronic or paper form, and may be shared among individuals for purposes of scholarly research or discussion, but may not be republished in any form, electronic or print, without prior, written permission from the author(s), and advance notification of the editors of MTO.

[2] Any redistributed form of items published in MTO must include the following information in a form appropriate to the medium in which the items are to appear:

This item appeared in Music Theory Online in [VOLUME #, ISSUE #] on [DAY/MONTH/YEAR]. It was authored by [FULL NAME, EMAIL ADDRESS], with whose written permission it is reprinted here.

[3] Libraries may archive issues of MTO in electronic or paper form for public access so long as each issue is stored in its entirety, and no access fee is charged. Exceptions to these requirements must be approved in writing by the editors of MTO, who will act in accordance with the decisions of the Society for Music Theory.

This document and all portions thereof are protected by U.S. and international copyright laws. Material contained herein may be copied and/or distributed for research purposes only.

Prepared by Hoyt Andres, Editorial Assistant

Number of visits: