Johann Georg Sulzer’s “Recitativ” and North German Musical Aesthetics: Context, Translation, Commentary*

Matthew L. Boyle

KEYWORDS: Agricola, Berlin, Graun, Hamburg, Kirnberger, recitative, rhetoric, Scheibe, schemata, Schulz, Sulzer, Telemann, text and music

ABSTRACT: Johann Georg Sulzer’s “Recitativ” is a uniquely ambitious article in his Allgemeine Theorie der schönen Künste. The longest music article in his encyclopedia and accompanied with over 100 musical examples, it describes the technical features and expressive functions of the genre of recitative through 15 rules. It also documents a regional dispute between Berlin and Hamburg over the composition of recitative. Georg Philipp Telemann and Johann Adolf Scheibe, composers associated with Hamburg, are chastised in “Recitativ” for their willingness to abandon Italianate formulas and adopt French or newly invented techniques. In contrast, the Berliner Carl Heinrich Graun is celebrated, with passages of his recitative used as stylistic exemplars. In the years before the publication of “Recitativ,” a diverse group of musicians in Berlin beginning with Graun expressed distaste for French-influenced recitative, including even the Francophile Friedrich Wilhelm Marpurg. The article is the product of collaboration between several Berliner authors who express their city’s Italianate taste in recitative, including Sulzer, Johann Abraham Peter Schulz, Johann Kirnberger, and Johann Friedrich Agricola. New evidence suggests that Agricola’s influence on the article is greater than previously acknowledged. Sulzer’s text is presented in a side-by-side translation that includes his 39 numbered musical examples, with added bibliographic commentary and translations of poetic texts (also downloadable as an Appendix).

Copyright © 2017 Society for Music Theory

Mein damaliger Aufenthalt an einem Orte, wo ein gekrönter Weltweise das prächtigste der Schauspiele, oder wie andre sagen, “das ungereimteste Werk, so der menschliche Verstand jemals erfunden,” die Oper einem Volke zeigte, so bisher dergleichen kaum dem Namen nach kannte; gab mir noch mehr Gelegenheit hierauf zu denken. Ein jeder sagte seine Meynung von Arien und Recitativen, als von den allergemeinsten Sachen, so daß die Oper der Vorwurf aller Unterredungen ward.

[Back then, my stay in one city gave me even more opportunity to think on this—a city where a crowned philosophus showed his people the most brilliant of plays (or as others say, the most absurd work that human reason ever invented): opera—for until then hardly any knew its name. Everyone spoke their opinion on arias and recitatives, as with the most common of things, so that opera became the topic of all conversations.]

– G. E. Lessing, Beyträge zur Historie und Aufnahme des Theaters, “Critik über die Gefangenen des Plautus.”

Introduction(1)

[1.1] Johann Georg Sulzer’s encyclopedia, the Allgemeine Theorie der schönen Künste (1771–74), has long been familiar to music scholars of the Enlightenment. The influence of its musical articles on musicians of the past is well-documented and hardly needs to be introduced here, especially because in recent years it has increasingly been drawn upon for evidence in a wide range of eighteenth-century musical topics, including historical theories of rhythm and meter, aesthetics, and topic theory.(2) Sulzer, an enthusiastic Liebhaber of music, enlisted the collaboration of skilled Prussian music theorists, most notably Johann Kirnberger, in preparation of music articles. Thomas Christensen’s 1995 translation of several articles on general aesthetic and musical topics in Sulzer’s encyclopedia has made major excerpts of this work accessible to English speakers.(3) Yet much still remains inaccessible. Christensen, who frames his translation project as a means of rendering Sulzer’s own thoughts and writings in English, justifies the inclusion of two music articles not by Sulzer (probably written by his collaborator Johann Abraham Peter Schulz), on the sonata and the symphony, according to the prestige of those genres alone. Christensen “deemed it appropriate to conclude with these articles,” because these genres are among the “two most important instrumental genres of the eighteenth century” (1995, 23). Their prestigious status furthermore allows them to “serve as fitting exemplars” to the “aesthetic and rhetorical principles explicated by Sulzer” at the capstone position of his curated translations (23).

[1.2] This, of course, reiterates a well-worn historical narrative that emphasizes the rise of instrumental music and marginalizes vocal music in Northern German circles during the Enlightenment. Christensen goes as far as to characterize Sulzer’s project as not only “the most ambitious attempt in mid-century Germany to integrate the new sensualist epistemology with classical aesthetic doctrine,” but one that “stands at an important juncture” in the history of music, accompanying the creation of a new aesthetic justification of instrumental music based on “the psychological processes studied so intently by the empiricist philosophers” (1995, 5). Sulzer’s solutions to these aesthetic problems led to his detailed description of the artistic process and a “revitalization of rhetoric” that “offer[ed] a solution for an aesthetic grounding of instrumental music” (6). Yet any fully fleshed-out demonstration of Sulzer’s justification of instrumental music is omitted from these articles.(4) His proposed aesthetic grounding of instrumental music is seen only in an incipient form in the articles “Sonata” and “Symphonie.” These articles, instead of being detailed applications of Sulzer’s rhetorical theories, are brief, spanning only two or three pages.(5)

[1.3] Yet we can already find a fully explicated genre-oriented article within Sulzer’s own publication, one that does not require a later theorist such as Heinrich Christoph Koch to complete the project’s promise. That music article discusses a genre with little prestige in modern musical culture, a vocal genre that was once debated with great vigor in northern German circles: recitative.(6)

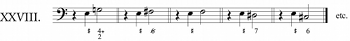

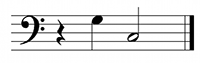

[1.4] The article “Recitativ” is lengthy, with nearly ten times the number of printed pages dedicated to it than the “Symphonie” article translated by Christensen. Unlike its shorter instrumental cousins, it does not suffer from “the lack of any detailed description [ . . . ] of the process by which [it] may be structured and composed” (Christensen 1995, 23). The “Recitativ” article contains 15 numbered rules regulating the composition and performance of recitative that are concerned with facilitating appropriate performance befitting good oration. Yet not all of its content is limited to detailed prose. In fact, the number of musical examples contained within it is staggering even by the standards of twenty-first century music journals. The article contains insert pages that hold 39 numbered musical examples, many of which have two or more sub-examples, elevating the number of unique examples on these pages to well over 70. Compounding this are over 40 additional musical examples integrated into the visual space of the printed prose. The article is also extensive in its scope. It includes, as already mentioned, sections devoted to the composition and performance of recitative. It also includes long polemical tracts and extensive discussions about the general aesthetic issues of recitative as a style, with reflections on such minutiae as the relationship between harmonic dissonances and poetry. Finally, it documents the reception of two central composers in eighteenth-century North Germany: Carl Heinrich Graun and, through the proxy of Johann Adolph Scheibe, Georg Philipp Telemann. Both Graun and Telemann assume prominent positions within a mid-century regional dispute over the composition of recitative.

Organization and Content

[1.5] Sulzer’s recitative article is a complex document penned by multiple authors. Most of its musical content was written by at least two musical experts (probably Kirnberger and Schulz). Additional commentary was probably added by Sulzer himself.(7) The article “Recitativ” is divided into three main sections and a bibliography. The first section (§1–10) comprises the opening half of the article. It defines recitative and concerns itself with general aesthetic issues. More specifically, recitative is seen as spanning the central position of a continuum between the extremes of song and speech, one that takes distinct pitches from song and rhythmic freedom from speech. Recitative properly belongs to specific genres (e.g, oratorio, cantata, opera) and is associated with poetic free verse. And even though, as argued by Rousseau, certain languages (like Italian) are better suited for recitative than others, talented poets can overcome the shortcomings of any language (§10). The rhythmic variety granted to recitative also is manifested in its expressive content, which can quickly vary from highly pathetic expression to plain narration. After this general introduction, the opening section shifts away from defining recitative to issuing prescriptive statements about how the style ought to go. Recitative, for instance, cannot be “indifferent” and cannot be used in the reading of letters as happens in Metastasio’s Catone in Utica (§5). Quite far from cool and indifferent verse, poets frequently reserve their best poetry for recitative, whose metrical and formal freedom offer possibilities freed from the constraints of arias (§7). The opening section finally introduces two emerging camps concerning the composition of recitative. One represents artistic and intellectual merit while the other epitomizes immense aesthetic failure. Representative of the former are the composer Carl Heinrich Graun and the librettist Karl Wilhelm Ramler, whose passion-oratorio Der Tod Jesu is first held up as an object of excellence in §7.(8) The composer and theorist Johann Adolph Scheibe—the emblematic representative of the latter—receives the first of many reprimands over his arcane distinction between “recited” and “declaimed” recitative in §6, a position outlined in his three-part “Abhandlung über das Recitativ” (1764–65). Scheibe’s treatise and compositions are the primary sources drawn upon for showing poorly composed and conceived recitative throughout the remainder of the essay.(9)

[1.6] The second major section of ”Recitativ” is dedicated to a list of fifteen rules governing the musical composition of recitative. These rules are often complex and evade simple reductions to a single underlying precept. Their contents can be summarized as follows:

- Recitative is rhythmically irregular and must follow the rhythm [Rhythmus] of the poetic text.(10) 4/4 meter is required. General differences between French and Italian recitative are outlined.

- The tonal and harmonic irregularity of recitative is described. Tonal features should align with the poetic text.

- A general prohibition on melismatic text setting in recitative is given.

- Syllabic text setting is prescribed. No musical embellishment should obscure the clarity of linguistic pronunciation.

- Accented syllables should be placed in accented parts of a measure.

- Rhythmic motion [Bewegung] must conform to good oration.(11)

- Melodic contour must conform to good oration.

- Rests must coincide with textual divisions.

- Cadences should appear only where the text demands it. Delayed cadences are possible.

- Questions and exclamations should emphasize a central word.

- Harmony should follow the text. Recitative is still subject to the rules of harmony.

- Dynamics should follow the text.

- Particularly moving passages should be set as arioso.

- There is a continuum between the rhythmic regularity of arioso and freedom of recitative.

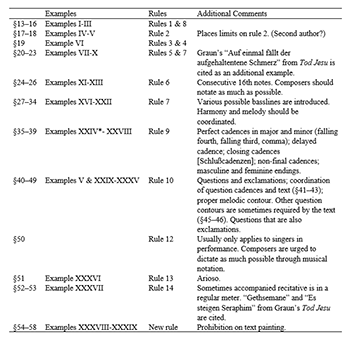

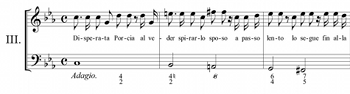

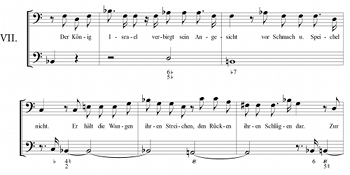

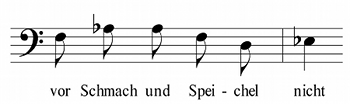

- Guidelines for appropriate locations of accompagnato are given.

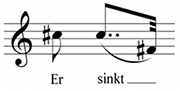

This second section concludes with a clue to the authorship of the essay. These fifteen rules were apparently shared with an anonymous “friend who combines the theory of music with a refined knowledge of good song.” This friend in turn was to have “volunteer[ed] a few comments on the following examples explaining the [fifteen rules]” (§12).(12) Even though these rules lie at the center of the essay, there are marked limitations to their explanatory power. Often it is unclear within the article exactly how the rules in “Recitativ” generate the examples of good recitative produced on its pages. For instance, the changes made to Scheibe’s recitative in §20 (the original appears as Example VII) only tenuously relate to their justifying rules. The very first of those presented (setting “Der König…”) supposedly corrects “errors against the fifth and seventh rules” (§20). The fifth rule regulates the location of accented syllables within a measure—placing them on strong beats. The seventh rule is much vaguer, calling for coordination between melody and the rising and falling sentiments of poetry. Yet neither rule calls for the revision made! The fifth rule has no relevance to the revision, as no syllable is even placed on a different beat. The seventh rule has more applicability in this situation only because of its vagueness. By urging composers to realize meaningful semantic segments of poetry through melodic contour, the evocation of the seventh rule can at best be understood as explaining why the revised version is better than the original—but in no way does it lead a composer to the in-text revision of §20. The prescriptive limitations of these rules place most of the explanatory weight within the third division of the essay on the revisions of flawed recitative and not on the rules themselves.

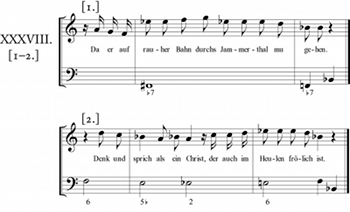

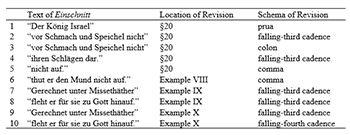

Table 1. Examples and rules discussed in the third part of Sulzer’s “Recitativ”

(click to enlarge)

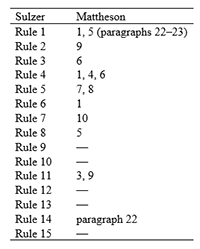

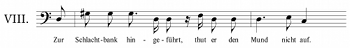

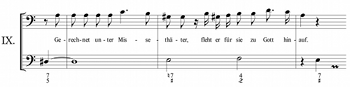

[1.7] The final major section consists of the comments solicited from “[a] friend” knowledgeable of song. In it well over 100 musical examples are discussed. Pieces by Scheibe and Telemann are chastised for violating the above rules, and works by Graun are held up as exemplars of sensitive text-setting. The organization of the third section, even with reordering and omissions, roughly follows the order of the preceding fifteen rules, as summarized in Table 1. When rules are discussed out of their numbered order, they do so through the pairing of a later rule with one presented in its proper position.(13) Two rules (11 and 15) are not directly addressed in this portion of the essay, although their general content finds its way into parts of the commentary. The author of this commentary even proposes some changes to the rules given in the second section and also offers an entirely new rule that prohibits text-painting (§§54, 56–57).(14) The discussion of these rules accompanies an aesthetic assessment of the musical examples that were presented on separate leaves, ostensibly assembled by the author of section 2. These examples are designated by Roman numerals.(15) Most of them are drawn from the works of two composers: Graun and Scheibe. Their recitatives are used respectively as “good and weak examples” to teach proper execution of the style (§12). Scheibe’s work in particular is thoroughly condemned as faulty.

[1.8] Scheibe was a controversial figure in the musical of life in mid-eighteenth century Germany. Best known today for criticizing J. S. Bach’s standing as a composer, Scheibe was an active composer and writer on music.(16) With the encouragement of his mentor Telemann, he founded the Hamburg-based journal Der critische Musikus in 1737. The aesthetic status of recitative was an idée fixe in his critical writings.(17) Wishing to salvage opera according to the classicist aesthetics of the University of Leipzig professor Johann Christoph Gottsched, who abhorred its non-imitative nature and lack of verisimilitude, Scheibe turned to recitative’s close relationship with oration in order to create an imitative justification for opera.(18) His earliest writings on recitative are found in the Critischer Musikus. Yet his most important work on the subject was published after his relocation to Copenhagen in the 1740s and includes a “report on the possibility and nature of good Singspiels” appended to his opera Thusnelde (Scheibe 1749), an open letter addressed to Wilhelm von Gerstenberg introducing his two Tragic Cantatas (Scheibe 1765), and a lengthy three-part treatise on recitative in the Bibliothek der schönen Wissenschaften und der freyen Künste (Scheibe 1764–65). Scheibe’s classicist leanings had him idealize the relationship between the contours of music and language, so much so that Scheibe proposed radical ways of rendering recitative that abandoned from time to time the foundational conventions of that style. These radical leanings align him with Telemann, who similarly experimented with alternatives to the highly formulaic Italianate recitative lingua franca. With so much of his own ink spilled on the subject and his prominent place within German music criticism, it should come as no surprise that Scheibe’s recitative and his writings on it were closely scrutinized by unsympathetic observers eager to point out its flaws.(19) In contrast, the recitative by Berlin-centered Carl Heinrich Graun is showered with praise throughout the Sulzer “Recitativ” article.(20) The marked preference for Graun over Scheibe left an impact on careful readers. The still-young Beethoven, trying to shore up his vocal writing, carefully studied these Graun examples, which influenced the recitatives in Christus am Ölberge and the various versions of Fidelio (Kramer 1973, 26–27, 37–43).

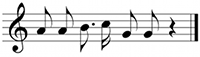

Performance, Composition, Oration

[1.9] The nature of successful performance is a central theme in “Recitativ,” one that is often tied to the composition of recitative and the practice of good oration. According to Sulzer, successfully composed recitative imitates the contours and rhythms of well-spoken language. In recitative the composer must recognize what the text affords concerning a rhetorically convincing recitation. Consequently the roles of composer and singer blend in recitative, so that their creative tasks both emulate that of an orator. It should then come as no surprise that the fifteen rules in the Sulzer article deal with recitative as oration in some manner, either as conforming to the rhythms of language (rules 1, 2, 5, 6, 8, 14, 15), the contour of language (rules 3, 7, 10, 11), or the affect and clarity of language (rules 2, 3, 4, 7, 9, 11, 12, 13). Here the composer rises to the role of orator, sometimes even surpassing the position of singer in this regard. Such an attitude is most clearly seen in the repeated suggestions that composers notate as much as possible regarding the execution of recitative and that singers defer their judgement to the composer. This is demonstrated by the prohibition of melismas (rule 3), a stance that limits the creative role of singers. It is also observed when, for instance, rule 12 is explained in §50 by advocating for greater notational precision: “it would likewise be better for both dynamics [piano and forte] and as well as tempo for each change of affect to be clearly prescribed to [the singer].” Or similarly, when the practice of not notating expected appoggiaturas is derided: “why is it then not written like that?” (§21). And more generally, “if it is true that much has to be left to the execution of the singer in recitatives, then it is equally true that it is absurd for a composer not to use everything in his capabilities to indicate to the singer the execution of each phrase” (§26). The role of composer as the primary interpreter of the text is best expressed by the quip “singers of course do not feel more than composers” (§26).

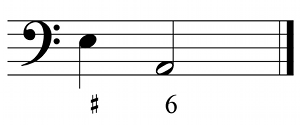

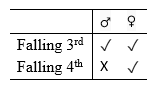

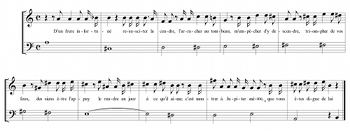

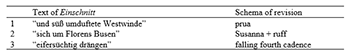

Table 2. Permitted cadences for “masculine” and “feminine” poetic rhythms

(click to enlarge)

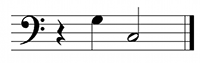

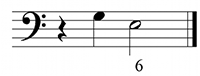

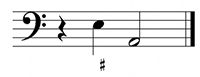

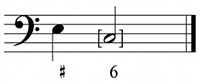

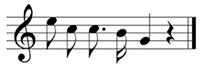

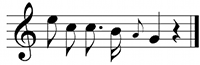

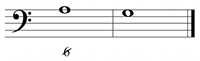

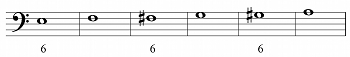

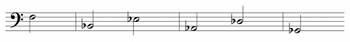

[1.10] The application and notation of appoggiaturas is also discussed in §39. Here the distinction between masculine and feminine cadences is outlined. Unfortunately the language in this paragraph is rather opaque. A falling-third “masculine” cadence is to be performed with an appoggiatura, even though the author proclaims a few sentences later that “no masculine cadence [should] be given a feminine ending” (§39). This commentary accompanies in-text examples of a falling fourth cadence which resists an appoggiatura due to its “extremely dragging” quality.(21) This paragraph is woefully under-explained. Its lack of clarity stems from a propensity to fuse compositional and performative elements. First, appoggiaturas are more or less shown to be obligatory in performance, either as melismas (in “masculine endings”) or in conjunction with syllabic text-setting (in “feminine endings”). Again, according to this essay such appoggiaturas should also be notated by the composer, even though this was not the usual notational practice for eighteenth-century recitative, a fact alluded to by the author in §39. Second, because the melismatic appoggiatura that is produced with “masculine” falling-fourth cadences is aesthetically questionable, “masculine” falling-fourth cadences are to be avoided, as summarized in Table 2. The cause of the aesthetic questionability of this particular appoggiatura cannot be explained from the second section’s rules alone. Even though such an appoggiatura can be seen as violating rule 6 by interrupting the natural rhythm of language and violating rule 4’s ban on short melismatic passages, those rules should also prohibit the stylistically sanctioned melismatic appoggiatura over falling-third cadences. For those cadences, the ubiquitous stepwise appoggiatura (essentially a passing tone) apparently lacks the “dragging” quality that a melismatic leap of a third creates in a falling-fourth cadence.(22) Not all relevant stylistic information is encoded in the article’s fifteen rules, which is a recurring problem in this essay.

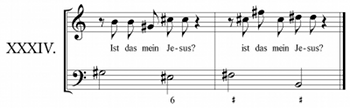

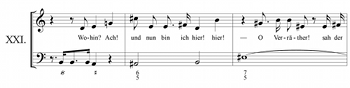

[1.11] The most idiosyncratic compositional prescription in the “Recitativ” article regards the setting of questions. Rule 10 stipulates that “the specific types of cadences through which questions, intense exclamations, and sternly commanding phrases are illustrated should not be made on the last syllable of the phrase but rather on the main word whose meaning this figure of speech rests on.” Placing the questioning tone on the word that a question is centered on can result in an unstylistic excess of post-cadential syllables, as shown in the integrated example of §44. No other important commentary on recitative calls for such a practice. This unusual position is even acknowledged within the essay, as the stipulation of rule 10 is found to be in direct opposition to the practice of a “majority of composers” (§41). The author felt that the usual manner of setting questions, which misrepresents the true meanings of poetic texts, violates the imperative for recitative to imitate the practices of good oration. Standard formulas of composing a question, with the last accented syllable coinciding with the question contour, are seen as potentially distorting the meanings of religious texts, and even able to transform some pious questions into shocking blasphemies (see §42). Due to the author’s radical and idiosyncratic understanding of questions, and since the repertoire could not yield music that follows the extreme position outlined in rule 10, faulty examples by Scheibe are never countered with successful ones by Graun (the most common strategy in other portions of this essay). Instead, newly composed revisions are used to illustrate the desired treatment of questions.

Hamburg and Berlin: Telemann and Graun

[1.12] The stark opposition between Graun and Scheibe’s recitative styles underlying the “Recitativ” article fits into a larger discourse that contrasted the ideal recitative styles of two North German musical centers: the port cities of Hanseatic Hamburg and Danish Copenhagen, on the one hand, and Prussian Berlin, on the other.(23) Sulzer was strongly linked to the Prussian capital of Berlin, where he was a member of the Royal Prussian Academy of Sciences. In Berlin, good recitative became increasingly associated with a well-established Italianate idiom, one spread throughout Europe by popular genres such as Metastasian opera seria. This Italianate or galant idiom has recently been described by Paul Sherrill and myself (Sherrill and Boyle 2015) as distinctive from other contemporaneous musical styles, by consisting of roughly 15 unique melodic schemas deployed in a highly scripted manner.(24)

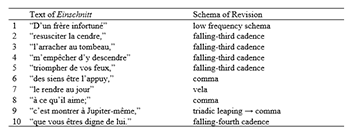

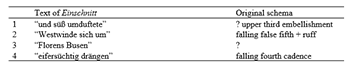

Table 3. Revisions to Example VII in Sulzer “Recitativ”

(click to enlarge)

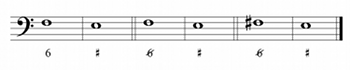

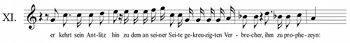

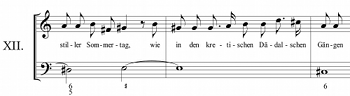

[1.13] Mid-eighteenth-century Berliner musicians, even those who often have contradictory opinions regarding music, repeatedly corrected phrases of recitative that deviated from this narrow vocabulary of melodic schemas. The “Recitativ” article does this in several locations, perhaps most notably in its discussion of a recitative from Scheibe’s Die Auferstehung und Himmelfahrt Jesu (Example VII). The opening poetic Einschnitt (“Der König Israel”), which Scheibe sets as an ascending arpeggio, is non-prototypical for galant recitative and does not correspond to any schema found in the roster of schemas produced in Sherrill and Boyle 2015.(25) The proposed alternative in the Sulzer article (§20) evens out the initial stage of the arpeggiation by having the voice only intone F for the first 3 syllables. This in turn transforms the opening passage into what we call a “prua” schema. Nearly every moment of musical and poetic punctuation (e.g., the ends of sentences and clauses) is subsequently criticized and corrected from Scheibe’s non-schematic forms to prototypical realizations of the schemas found in our roster. Table 3 summarizes these revisions.

[1.14] Friedrich Marpurg, also writing in Berlin, similarly revised passages of recitative in his Kritische Briefe über die Tonkunst.(26) In particular, he was quite sensitive to what he considered to be the differences between Italian and French recitative. In his CXV and CXVI letters (395–404) he examines a recitative from Rameau’s Zoroaster and provides three reworkings of it by three unnamed composers who attempted “to give Italian clothing to the French text of the preceding recitative.”(27) Each of these examples largely conforms to the schematic lexicon of galant recitative except for the first, which Marpurg criticizes for having poorly placed rests and poor deployment of schemas vis-à-vis their semantic connotations (e.g., a question cadence appears where none is called for). Marpurg in turn formalizes the schematic language of galant recitative to some extent by providing a typology of recitative cadences along with dozens of examples.(28) Moreover, earlier in his letters Marpurg maps onto this stylistic opposition of French versus Italianate recitative another opposition of greater consequence for practicing musicians: that of good (i.e. modern) versus antiquated taste. In the XCVII letter, Marpurg equates Italian recitative with modern music and calls it “new recitative” (neuere Recitativ), instructing his readers in the nuances of its composition, and contrasts it with French recitative which he describes as representative of older musical tastes (ältere), implied to be of little value to practicing musicians (255). This stance apparently offended a reader of Marpurg’s curious periodical who privileged French recitative as truer to the ancient Greek forms of recited speech (269). Out of character, Marpurg—a famous defender of French music in Berliner circles—dismissed these claims concerning French recitative, and responded with a point-by-point refutation in his XCIX letter, even rebarring a passage from Lully’s Armide to a consistent

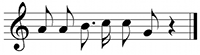

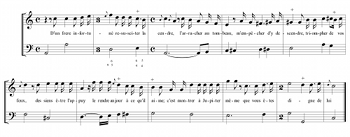

Example 1.1. Recitative passage from Jean-Philippe Rameau’s Castor et Pollux Act 1, scene 5, with only minor deviations from the published score (cf. Rameau 1737, 62–63). Graun included it as his first example in a November 9, 1751 letter to Telemann

(click to enlarge)

Example 1.2. Graun’s revision of Example 1.1 in an Italianate idiom and included as his second example in a November 9, 1751 letter to Telemann

(click to enlarge)

Table 4. Schematic summary of Graun’s November 9, 1751 revisions of Rameau’s Castor et Pollux Act 1, scene 5

(click to enlarge)

[1.15] Even two decades before the publication of Sulzer’s encyclopedia, musicians in Berlin expressed similar values concerning how modern recitative ought to sound. In 1751–52 Carl Heinrich Graun and Georg Philipp Telemann exchanged a series of letters on an array of topics including text setting, counterpoint, aesthetics, and recitative.(30) Their discussion of recitative powerfully illustrates the aesthetic divide between Hamburg and Berlin—as articulated by the premier composers of each city—and prefigures the aesthetic values argued for in Scheibe’s published essay and the Kirnberger-inflected Sulzer article. In the first surviving letter (May 1, 1751), Graun emphasizes that he does not dismiss all French music.(31) Instead, Graun’s distaste is reserved only for French recitative: “rather I only wanted to say that I consider the French recitative style as not natural, therefore I wrote that I have not yet seen a reasonable one because these same recitatives are set next to their mistimed and misapplied arioso melody absolutely too often and more often contrary to musical rhetoric: the operas of Rameau are proof enough.”(32)

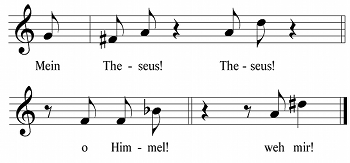

[1.16] In the next surviving letter (November 9, 1751), Graun elaborates his position by attaching eight musical examples with commentary. The first of these (Example 1.1)(33) presents a short excerpt from Rameau’s Castor et Pollux that supposedly exemplifies the misuse of arioso and rhetoric.(34) Graun’s second example (Example 1.2) offers a revision of this passage that transforms not only its rhythmical, metrical, and harmonic dimensions, as observed in Calella 2004, but quite notably translates nearly every melodic Einschnitt into a schema from Paul Sherrill’s and my 2015 roster. All of these revisions were introduced by Graun with the aim of having “Telaire…seek to sway Castor more emphatically.”(35) Here as elsewhere, rhetorical clarity is only recognized when recitative conforms to an Italianate schematic regularity; see Table 4 for a summary of these revisions. Graun’s inelegant, Schusterfleck-inflected recitative prefigures some of the prescriptivist commentary found in the Sulzer “Recitativ” essay, with rising chromatic basslines appearing in §27 and again in the first section of Example XVI.(36) Sulzer urges his readers to use similar rising chromatic basslines in moments of crescendoing dramatic intensity, much as Graun wishes Telaire to address Castor more intensely. The examples demonstrating this practice (Examples XIV and XV) in “Recitativ” are recitatives by Graun that make use of this very same bass “transposition.” Example XIV is remarkable in that each stage of the cadential transposition is punctuated with a falling-third cadence, just as Graun’s own revision above does. In the final two recitative examples (No. 7–8) in Graun’s letter to Telemann, Graun, like Marpurg above, revises another recitative from Rameau’s Castor et Pollux, so that its unchanged melody may remain in common time throughout.

[1.17] Telemann’s only surviving response concerning recitative (dated December 15, 1751) rejects Graun’s assertion that Italianate recitative is more natural and more suitable for composition. In contrast, Telemann encouraged greater experimentation and was reluctant to claim that the Italian style had won permanent international prominence.(37) Both he and Scheibe imagined creative ways for how the relationship between language and music ought to be negotiated. Telemann eventually adopted Rameauvian (i.e., French) recitative techniques in his latter sacred works, including his Matthew Passion, an excerpt of which Telemann sent to Graun in this correspondence. The characteristic metrical changes of French recitative are celebrated for their fluidity. He writes, for instance, that in the French style “everything goes on to the next like the wine of Champagne.”(38) Telemann further defended his position through a critique of Graun’s eighth example—the common-time rebarring of Rameau—in which he expresses skepticism as to whether more than three sixteenth notes in succession would be stylistically appropriate for Italian recitative: “[this] also catches my eye at ‘préparer la fête,’ since I cannot recall to have found in a Welsh [i.e. Italian] recitative four sixteenth notes in a row.”(39) Telemann appears to have only expressed this sentiment within this letter—it does not appear in his primer on recitative published with his Harmonischer Gottes-Dienst (1725–26). Sulzer’s “Recitativ” article, curiously, belittles this stylistic judgement: “Many composers of vocal music want recitative never to have more than two—at most three—sixteenth notes following each other. This is exactly observed in Telemann and Scheibe’s recitatives. In their tragic cantatas, the accent of language and the natural metrical weight is sooner violated than this rule” (§25). Did Graun, the central composer of mid-century Berlin, gossip to his compatriots about Telemann’s unorthodox ideas concerning recitative?

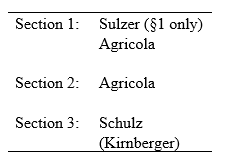

Author(s)

[1.18] The authorship of the music articles in Sulzer’s encyclopedia had long been attributed to Kirnberger and his student Schulz. These attributions rested on two documents: Sulzer’s preface to the second volume of the Allgemeine Theorie and an 1800 article by Schulz that appeared in the Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung (AmZ).(40) From these accounts it would seem that (1) Kirnberger was responsible for all music articles in the first volume (ranging from letters A to J) and most early articles in the second volume (letter K through “Modulation”), (2) that his student Schulz collaborated with him from after “Modulation” through R, and that (3) Schulz more or less independently wrote the articles from S onward. We also know from Schulz’s 1800 AmZ essay that Kirnberger was still responsible for some of the articles after S, including both “System” and “Verrückung.”

[1.19] Beverly Jerold has recently challenged these consensus attributions by proposing that Sulzer solicited articles from other musicians before Kirnberger was brought into this project (2013, 694). Her suspicion is that the Prussian court composer Johann Friedrich Agricola (1720–1774)—an opera composer, accomplished tenor, vocal pedagogue, and published writer on music—contributed to many of the music articles in the first volume of the Sulzer encyclopedia.(41) If so, then Kirnberger arrived only relatively late in the preparation of the first volume. The plausibility of Agricola as a collaborator is quite appealing even when only considering the general content of the music articles. The Musik in Geschichte und Gegenwart article on Sulzer observes that a noticeable shift in musical subject matter occurred between the first and second volumes, with instrumental topics receiving greater prominence in the second volume and vocal topics greater prominence in the first, which can be elegantly explained with Agricola as a contributor to the first volume (Jerold 2013, 696). There are other indications both within Sulzer articles and in contemporary documents that suggest the presence of another musical collaborator, likely to be Agricola. One such indication is that the music articles are sometimes profoundly ideologically inconsistent. Kirnberger, infamous for his contentious rivalries with other Berliner musicians, seems unlikely as an author of articles that praise his known rivals. These inconsistences are most noticeable between articles on related topics. Open endorsement and praise for Rameau’s harmonic theories, quite out of character for the anti-French Kirnberger, can be found in alphabetically early entries such as “Accord,” “Auflösung der Dissonanz,” “Cadenz,” and “Harmonik” (Jerold 2013, 607–98; Christensen 1995, 14). Another indication is that eighteenth-century writers attributed authorship to Agricola. Ernst Ludwig Gerber, for instance, listed both Agricola and Kirnberger as authors in his 1792 Historisch-biographisches Lexicon der Tonkünstler (Jerold 2013, nn 10, 25). Johann Joachim Christoph Bode, in a 1773 translation of Charles Burney’s travels through Central Europe, also states that Agricola wrote articles for the Sulzer encyclopedia, even attributing the article “Ausdruk in der Musik” to him (Jerold 2013, 696).(42) It is also known that Agricola preferred to remain anonymous in public disputes, which perhaps explains why Sulzer never acknowledged him in the prefaces to the Allgemeine Theorie (696).

[1.20] The vast majority of material found in the Sulzer article on recitative has been attributed to Schulz. Richard Kramer suspects that multiple authors may have had minor roles in its creation, with Sulzer “responsible for [the] first section” and with Schulz as the exclusive author of the more overtly musical sections (1973, 24). Kirnberger’s role was only to provide an “editorial eye [as Schulz’s] mentor” (24). In this interpretation nearly all of sections 2 and 3 were penned by Schulz (24). Frederick Neumann, in his 1982 study of appoggiaturas, similarly attributes the recitative article to Schulz, as does Clive Brown 1999. Claude Palisca credits the article only to Kirnberger and Sulzer (1983, 11). Yet ascribing the musical content primarily to Schulz (or Kirnberger) ignores aspects of the article that openly acknowledge multiple authors. The second section, for instance, contains a passage that claims that the third section was written by a different author from the preceding one, an author “who combines the theory of music with a refined knowledge of good song” (§12).(43) It is also implied within §12 that the author of the second section was responsible for collecting at least the majority of the numbered musical examples discussed in section 3.

Table 5. Authors of Sulzer’s “Recitativ” as proposed by Jerold (2013)

(click to enlarge)

[1.21] Jerold interprets this as marking a change in author at the beginning of the third section. Sulzer, in her estimation, was responsible only for the opening paragraph on classical subject matter. She concludes that the remainder of the first and the entirety of the second sections were penned by “an individual active in the vocal arts,” who in the first section claims to have “written the article ‘Oper’” in §5 (2013, 694). Jerold suspects that Kirnberger played a minimal role in the creation of the article, and that his role was largely limited to adding polemically-charged interjections critiquing Telemann’s text painting practices (§54) to an article otherwise written by Schulz, Sulzer, and a vocal expert likely to be Agricola (649). Jerold’s views of authorship in each major section of the article are summarized in Table 5.

[1.22] I believe it is likely that Agricola contributed to the composition of this essay, but I do not believe that he could have been the sole contributor to the second section’s list of rules, as some of these rules contradict views presented in writings on recitative known to be by Agricola. In his 1757 translation and expansion of Tosi’s 1723 Opinioni de’ cantori antichi, e moderni (published as Anleitung zur Singkunst), Agricola advocates for and instructs in the appropriate use of melismas and embellishments in recitative, providing additional musical examples and prose commentary to Tosi’s treatise. This stands in sharp contrast to the prohibition of and limitations on melismas and embellishments found in rules 3 and 4 of the Sulzer essay. Moreover, no vocal expert was needed to assemble the 15 rules of section 2, nor does the essay imply that the author of section 2 is a vocal expert. The turn of phrase heralding the entry of a new author in §12 seems to indicate that the vocal expert penned section 3. Obviating Agricola’s role further is the fact that these 15 rules could easily have been drawn together from a readily available source, namely Johann Mattheson’s 1739 Vollkommene Capellmeister. Mattheson, in a section discussing vocal melodies, outlines 10 rules governing the successful composition of recitative which are preceded by two general paragraphs on the unique properties of recitative. Mattheson’s rules are as follows:

- It should not be constrained at all, but should be completely natural.

- The accent must receive a great deal of attention with it.

- The affect must not suffer the slightest detriment.

- Everything must fall lightly and understandably on the ear as if it were spoken.

- Recitative more exactly insists upon the correctness of Einschnitts than all arias, for with the latter, one is occasionally somewhat forgiven because of pleasant melody.

- Actually, no melismas [Melismata] or more frequent repetitions belong in recitative with the exception of some quite special though rare cases.

- The accent is not to be disregarded for a moment.

- The caesura of the measure, though it pretty well takes care of itself, nevertheless must be properly attended to in writing.

- The established style of writing with all its familiar clauses must be retained and yet must always bring something new and different in variation of tones. This is the most important point.

- The greatest conceivable variation in the rising and falling of the sounds must be sought, especially in the bass, but as if it occurred by chance and certainly not contrary to the meaning of the words.(44)

Table 6. Concordances between the rules governing recitative in Mattheson 1739 and Sulzer 1771–74

(click to enlarge)

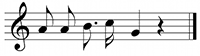

Example 1.3. Agricola’s revision of a passage from Scheibe’s Ariadne auf Naxos. Compare with Examples XII and XIII.

(click to enlarge)

Nine of Mattheson’s rules concord with “Recitativ,” and those rules that do not share content with Mattheson’s either focus on idiosyncratic advice (such as the application of dynamics), cadence types, or the use of accompagnato and arioso. And although Mattheson was a Hamburger like Telemann, his idealized recitative style featured both the rhythmic clarity and schematic regularity (cf. rule 9’s “familiar clauses”) called for by “Recitativ.” The relationships between these two sets of rules is summarized in Table 6.

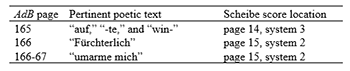

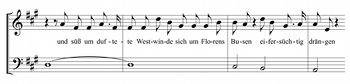

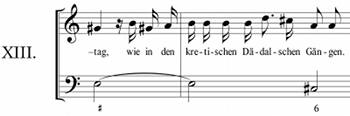

[1.23] Yet Agricola’s involvement with the article need not be limited to section 1. The final portion of the essay, even if primarily by Schulz, at the very least emulates the argumentative style of a review essay now known to be by Agricola, an essay that critiques Scheibe’s recitatives in the Tragic Cantatas. In many ways Agricola’s 1769 review article in the Allgemeine deutsche Bibliothek (AdB), published five years before the Sulzer, seems to be a “practice run” for several of the central arguments found in the Sulzer article.(45) Both essays share points of contact concerning aesthetic outlook, perceived stylistic faults of Scheibe’s recitatives, and even musical examples and their discussions. Perhaps the most clearly noticeable commonality between the two essays is the shared criticisms of a single passage and their very similar corrective revisions of it. Scheibe’s setting of the word “kretischen” troubled both Agricola and the author of the Sulzer comments. Agricola, whose essay has a running theme noting how Scheibe the composer deviates from the advice of Scheibe the critic, notes that “Hr. S.[cheibe] would certainly not have let another composer sneak through unchastised” if they were to have similarly set the last syllable of kretischen on the third beat of a measure.(46) In §25 of the Sulzer essay, this passage is cited as Example XII for the same reason, that of having an “unnatural metric weight on the last syllable of kretischen.” Both essays also propose near-identical corrections. Agricola’s AdB review ensures that the first syllable of kretischen falls on the first beat of the measure, as seen in Example 1.3.

[1.24] His revision features a somewhat uncharacteristic mixture of quarter notes into the rhythmic notation of the recitative. Agricola’s notational solution is not the only one available, and in fact, when a similar revision is proposed as Example XIII in the Sulzer essay, the quarter notes setting “-dal-schen” are compressed so as to allow the accented syllable of “Gängen” to fall on the third beat of the measure instead of the beginning of the following measure. The notational practices of both revisions help to clarify differences in their immediate use in the respective essays. For Agricola’s AdB review, the quarter-note notation is used to demonstrate that, contrary to the practice of composers such as Scheibe and Telemann, sixteenth notes and quarter notes may be mixed (164). In fact, Scheibe’s error, according to Agricola, emerges out of his faulty understanding of this aspect of the style: “We can imagine no other reason for his method than that he wanted to avoid the meddling, common for the Italians in their recitative, of multiple sixteenth notes and quarter notes. For in both cantatas we can find nothing of the sort.”(47) The qualms composers like Scheibe had in writing such rhythms is purportedly misplaced because an experienced singer in performance will not mechanically differentiate between the rhythmic value of quarters and sixteenths: “But, since a skillful singer of this type of recitative will sing the sixteenth notes as little [wenig] as the quarter notes in their true metrical value [Taktgeltung], this then appears to us to be an exaggerated subtlety, one which traces the most assured error of a wrong declamation in notes and words.”(48) The Sulzer essay similarly attempts to correct a perceived error in the notation of rhythm, namely that instead of the practice of “many composers” (again Scheibe and Telemann) “never to have more than two—at most three—sixteenth notes following each other,” composers should follow the metrical weight of syllables and feel free to use many sixteenth notes that “would show the singer that he should quickly pass through words which have no striking meaning” (§25). The similarity between these two passages suggests, at the very least, that the AdB review influenced the Sulzer essay, but it may indicate that Agricola worked partially on the final section of the Sulzer article.

Table 7. Passages from Scheibe 1765 (Ariadne auf Naxos) revised by Agricola 1769

(click to enlarge)

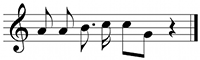

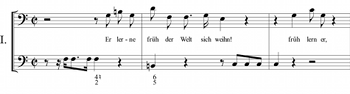

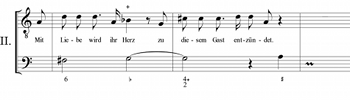

Example 1.4

(click to enlarge and see the rest)

Table 8. Schematic summary of Example 1.4a

(click to enlarge)

Table 9. Schematic summary of Agricola’s revision (Example 1.4b)

(click to enlarge)

[1.25] The remaining recitative revisions in Agricola’s AdB review air grievances concerning poor text-setting (see Table 7 for a catalogue of these). Yet just as with Marpurg, Graun, and the Sulzer essay, Agricola uses these revisions to reinforce the schematic normalcy of the Italianate style and, through the repeated evocation of proper text-setting, hereby associates these schemas with rhetorical clarity. The first entry in Table 7 is the most extensive of these revisions. Agricola begins by describing its flawed declamation of the syllables “-te,” “West,” and “win-.”(49) He then provides a score excerpt of both Scheibe’s recitative (Example 1.4a) and his own revision of that passage (Example 1.4b). After giving this revision, Agricola matter-of-factly asks: “is the following not better and clearer?” (1769, 166). And it certainly is. Scheibe’s original is littered with problems from a Berliner’s perspective. He neither follows the poetic Einschnitts implied in the German text nor properly uses the Italianate lexicon of recitative schemas to musicalize them.(50) As seen in Table 8, only half of the recitative’s gestures in Scheibe’s original unequivocally present Italianate schemas, whereas Agricola’s revision, summarized in Table 9, is in this respect perfect. The very clarity that Agricola finds so easy to recognize must lie equally in a passage’s conformity to melodic prototypes as well as its more general rhythmic profile. Agricola’s attitude regarding this is almost to be expected: it is remarkably consistent with those of his contemporary Prussian compatriots, being especially concordant with the general tone of “Recitativ,” an article he himself may have played quite an active role in shaping.

Conclusion

[1.26] The most ambitious aspect of “Recitativ” is that it provides a holistic description of a musical genre, in which the basic rules of a “genre game” are outlined. These idealized rules for recitative are described (and prescribed) using the best intellectual technology available to Sulzer’s collaborators: a catalogue of 15 rules and a discussion of stylistic exemplars. Yet the methods in “Recitativ” only partially capture the nuances of this relatively simple musical style. His numbered rules model the formulaic language of Italianate recitative as well as a bottom-up strategy could be expected to describe a category-based musical practice. More crucial to his project, even if less systemized, was the Berlin practice of revising recitative—a ripe tradition for Sulzer’s encyclopedia to draw upon in defending stylistic judgements. Through the revision of faulty passages of recitative, Sulzer was able to convey denser packets of stylistic knowledge more effectively and efficiently than through his 15 rules alone, by calling attention to and demonstrating the proper usages of Italian recitative schemas. In conjunction with each other, both the 15 rules and the numerous musical exemplars paint a coherent picture detailing Sulzer’s vision for the expressive and aesthetic function of recitative.

[1.27] An often alluded-to theme regarding the expressive function of recitative is found in the distinction between recitative and aria, sometimes expressed through the divide between Italian and French recitative. All of these distinctions are created through the use of specialized, genre-specific lexicons of schemas. Moreover, Sulzer’s discussion of recitative reveals his understanding of the structural and expressive role of recitative within larger vocal genres. Italian recitative embodies an ideal form of rhetorical clarity largely through its melodic and rhythmic simplicity. Such simplicity facilitates the singing character’s ability, like a skilled orator, to move their audience through the power of (musicalized) spoken rhetoric. French recitative, in contrast, is too invested in expressing the affective state of the singer at each moment and consequently is too much like aria. After all, Graun—the model composer for “Recitativ”—lists in the above cited 1751 letter the “mistimed and misapplied arioso melody” as the primary cause for French recitative’s propensity to be “contrary to musical rhetoric” (Telemann 1973, 274). Aria, like arioso, in turn differs from recitative by its more temporally structured expression of passion (cf. §4). The commentary to the revisions in “Recitativ” and the repeated discussion of “special types of cadences” also indicate that for the authors of Sulzer’s “Recitativ” (and probably Graun in 1751) the schematic parsimony of Italianate recitative and good declamation were inseparably connected. Deviations away from this limited vocabulary of recitative schemas was seen as an abandonment of good declamation, a step towards Gallic recitation, and ultimately as signaling the encroachment of aria-like expression in a poetic space dedicated to a drastically different form of expression. Telemann and Scheibe’s schematically imaginative realizations of language shied away from the formulaic vocabulary of the Italian style, and by doing so, their very novelty endangered the very expressive function of the genre. Unsurprisingly, many of the listed rules in the Sulzer essay steer composers away from the too arioso-rich style of French recitative by consistently deferring purely musical invention to the natural rhythms and contours of language, represented by a limited Italianate lexicon. Innovative melodic composition in recitative is to be avoided at all cost. The goals of Sulzer’s “Recitativ” are as diverse as they are ambitious. No wonder such a wide array of authors were employed in its creation. Sulzer could contribute his knowledge of Classical writings, Kirnberger and Schulz could contribute a systematic approach to musical thought, and Agricola could serve as the vocal expert guiding the essay through the finer details of the recitative style. Altogether, grounded in mutual respect for Graun, they voice a unified vision of a musical genre for Berlin, a rare sound of harmony in an otherwise ideologically diverse city.

Translation

[1.29] In any translation difficult decisions have to be made concerning the level of faithfulness to many aspects of language such as underlying metaphors, rhetorical timing, and the register of terminology that can be preserved. I have tried wherever I could to make my English rendering of this article as much like the German as possible. In a century when Germans were highly sensitive to the linguistic roots of words (and even morphemes), I find it misleading, for instance, to transform simple, Germanic words that transparently display their meaning into more erudite Latinate words. I leave the German term Einschnitt untranslated throughout my translation instead of using its English-approximate “incise,” popularized by Nancy Baker (1983). Baker methodically decided to render Einschnitt using the French grammatical term “incise,” hoping to “retain [the] ambiguity of meaning” that appears in Koch’s usage of the term (Baker 1983, xxiii). Baker’s solution is probably the best possible for English. Yet, even so, “incise” hardly occupies the same linguistic register as Einschnitt. As Baker’s groundbreaking work on Heinrich Koch has made the concept Einschnitt more familiar to Anglo-sphere music scholars, the need for a familiarizing English rendering is less urgent than it was forty years ago. As Eckert 2007 argues, the meanings of the terms Einschnitt and Abschnitt are too complex to simply reduce to a single English term.(51)

[1.30] I have also tried to avoid translating the same word differently within a single sentence or paragraph. The use of the word Ton is particularly charged with multiple meanings throughout the essay, making it tempting for a translator to overtly unravel those meanings with each appearance. Yet the use of Ton in the German text portrays that inseparable union between music and oration central to the Sulzer essay. One of the most semantically dense passages concerning Ton in the article appears in the second section. Ton, a German word with a similar range of meanings to the English “tone,” can signify a note, a key, a timbre, a whole step, the quality of a voice, or the semantic quality of spoken or written language. Sulzer’s encyclopedia dedicates three separate entries to Ton, one for its musical uses, another for its uses in the “Redene Künste,” and still another for painting. In the second rule, Ton and its derivatives appear (depending on how one counts) at least seven times within three short sentences. Its meanings within this passage are entwined, unable to be linguistically disentangled without a loss of meaning. The “quick departure to other tones” applies, for instance, just as well to tonal centers as to the more general tone of a passage (i.e., a rhetorical sense of tone) (§11). Consequently, in order to be sensitive to the various shades of meaning presented by this word, I avoid unravelling Ton to its most probable English meaning at each moment, and instead rely on the judgement of the reader to infer its likely meanings. Even if the English result is sometimes stylistically awkward, translating Ton differently in every instance of its use would obscure a persistent use of language that elegantly unites music and rhetoric.(52) In general, I have tried to be as faithful as possible to the metaphors and syntax of the German original.

[1.31] One respect in which I do not attempt always to reproduce German as exactly as possible in English concerns the use of pronouns. Wherever possible, I have rendered phrases using the German pronoun man as its subject in the passive voice, in recognition of its stylistic similarity to the French on. The gender of German pronouns also sometimes presents unusual situations. The last sentence of §25 has a masculine noun antecedent [Sänger] referred to by the pronoun er [he]. I translate er as she to conform to the gender of the character in Scheibe’s cantata.

[1.32] I also provide translations of the text set in the appended musical examples. Whenever the example only presents a fragment of a sentence, I add preceding or following text in order to aid in comprehensibility. This is always indicated through italics.

Sources

[1.33] The primary text consulted for this translation is that of the first edition (1774), published in Leipzig by M. G. Weidmann in two volumes, in 1771 and 1774. Several reprints and revised editions of the Sulzer encyclopedia appeared in the later decades of the eighteenth century. I consulted two of these later printings, both of which are expanded editions. The first of these enlarged editions was published in four volumes from 1786–87. The second edition of this text was published from 1792–94 and is now easily accessible in a 1967 facsimile reprint by Georg Olms Verlag. The main body of the text is near-identical in all editions, with only corrections to small typographical errors differentiating them. The two expanded editions, however, append bibliographies of relevant literature on the topic of recitative that did not appear in the first edition. I include both of these bibliographies in the German text and in the English translation. The 1787 bibliography appears first in §59 and the 1794 one appears in §60–61.

Sulzer’s “Recitativ”: Edition and Translation

Recitativ.(53) (Musik) |

Recitative (Music). |

||

|

[2.1] Es giebt eine Art des leidenschaftlichen Vortrages der Rede, die zwischen dem eigentlichen Gesang, und der gemeinen Declamation das Mittel hält; sie geschieht wie der Gesang in bestimmten zu einer Tonleiter gehörigen Tönen, aber ohne genaue Beobachtung alles Metrischen und Rhythmischen des eigentlichen Gesanges. Diese so vorgetragene Rede wird ein Recitativ genannt. Die Alten unterscheideten diese drey Gattungen des Vortrages so, daß sie dem Gesang “abgesezte” Töne zuschrieben, der Declamation “aneinanderhangende,” das Recitativ aber mitten zwischen beyde sezten. Martianus Capella nennt diese drey Arten genus vocis-continuum, divisum, medium, und er thut hinzu, die lezte Art, nämlich das Recitativ, sey die, die man zum Vortrag der Gedichte brauche. Diesemnach hätten die Alten, ihre Gedichte nach Art unsers Recitatives vorgetragen; und man kann hieraus erklären, warum in den alten Zeiten das Studium der Dichtkunst von der Musik unzertrennlich gewesen. Die bloße Declamation wurd bey den Alten auch notirt, aber blos durch Accente, nicht durch musicalische Töne. [942] Dieses sagt Bryennius, den “Wallis” herausgegeben hat, mit klaren Worten. |

[3.1] There is a type of passionate delivery of speech that stands midway between actual song and common declamation. It occurs, like song, in tones belonging to a particular scale, but without exact observance of all the metrical and rhythmic aspects of actual song. Speech delivered like this is called recitative. The ancients differentiated these three types of delivery, so that they ascribed to song distinct tones; to declamation, continuous tones; and placed recitative in the middle between both. Martianus Capella calls these three types of genus vocis—continuum, divisum, medium.(54) He adds that the last type, recitative, is the one needed in the delivery of poems. Consequently, the ancients would have delivered their poems in the manner of our recitative; and from this it can be explained why, in antiquity, the study of poetry was inseparable from music. Mere declamation was also notated by the ancients, yet solely through accents, not through musical tones. Bryennius says this with clear words edited by Wallis.(55) |

||

|

[2.2] Von der bloßen Declamation unterscheidet sich das Recitativ dadurch, daß es seine Töne aus einer Tonleiter der Musik nihmt, und eine den Regeln der Harmonie unterworfene Modulation beobachtet, und also in Noten kann gesezt und von einem die volle Harmonie anschlagenden Baße begleitet werden. Von dem eigentlichen Gesang unterscheidet es sich vornehmlich durch folgende Kennzeichen. Erstlich bindet es(56) sich nicht so genau, als der Gesang, an die Bewegung. In derselben Taktart sind ganze Takte und einzele Zeiten nicht überall von gleicher Dauer, und nicht selten wird eine Viertelnote geschwinder, als eine andere verlassen; dahingegen die genaueste Einförmigkeit der Bewegung, so lange der Takt derselbe bleibet, in dem eigentlichen Gesange nothwendig ist. Zweytens hat das Recitativ keinen so genau bestimmten Rhythmus. Seine größern und kleinern Einschnitte sind keiner andern Regel unterworfen, als der, den die Rede selbst beobachtet hat. Daher entstehet drittens auch der Unterschied, daß das Recitativ keine eigentliche melodische Gedanken, keine würkliche Melodie hat, wenn gleich jeder einzele Ton eben so singend, als in dem wahren Gesang vorgetragen würde. Viertens bindet sich das Recitativ nicht an die Regelmäßigkeit der Modulation in andere Töne, die dem eigentlichen Gesang vorgeschrieben ist. Endlich unterscheidet sich das Recitativ von dem wahren Gesang dadurch, daß nirgend, auch nicht einmal bey vollkommenen Cadenzen, ein Ton merklich länger, als in der Declamation geschehen würde, ausgehalten wird. Es giebt zwar Arien und Lieder, die dieses mit dem Recitativ gemein haben, daß ihre ganze Dauer ohngefehr(57) eben die Zeit wegnihmt, die eine gute Declamation erfodern würde; aber man wird doch etwa einzele Sylben darin antreffen, wo der Ton länger und singend ausgehalten wird. Ueberhaupt werden in dem Vortrag des Recitativs die Töne zwar rein nach der Tonleiter, aber doch etwas kürzer abgestoßen, als im Gesang, vorgetragen. |

[3.2] Recitative is distinguished from mere declamation by taking its tones from a musical scale, observing a modulation subjected to the rules of harmony, and thus by being able to be set in notes and accompanied by a full, harmony-creating bass. It is distinguished from actual song principally through the following characteristics. First, it is not linked as precisely to tempo as song. Within the same meter, whole measures and single beats are not uniformly of the same duration, and not so rarely, one quarter note is abandoned more quickly than another. On the other hand, the most exact uniformity of tempo is necessary in actual song as long as the meter remains the same. Second, the rhythm of the recitative is not as exact.(58) Its large and small Einschnitte are subjected to no other rule than that which speech itself has observed. Thus arises the third difference, which is that recitative has no true melodic ideas—has no real melody—even when each individual tone is delivered just as songfully as in true song. Fourth, recitative is not bound to the regularity of modulation to other tones which is compulsory for actual song. Finally, recitative is distinguished from true song by never sustaining a tone noticeably longer than it would be held in declamation, even at perfect cadences. There are, of course, arias and songs that share this with recitative, so that their entire duration roughly takes just the time that good declamation would call for; but perhaps, for instance, particular syllables will be found where notes are sustained longer and [more] songfully. In general, of course, in the performance of recitative, tones are performed correctly according to the scale, although somewhat shorter and more detached than in song. |

||

|

[2.3] Das Recitativ kommt in Oratorien, Cantaten und in der Oper vor. Es unterscheidet sich von der Arie, dem Lied und andern zum förmlichen Gesang dienenden Texte dadurch, daß es nicht lyrisch ist. Der Vers ist frey, bald kurz, bald lang, ohne ein in der Folge sich gleichbleibendes Metrum. Dieses scheinet zwar nur seinen äußerlichen Charakter zu bestimmen; aber er hat eben die besondere Art des Gesanges veranlasset. |

[3.3] Recitative appears in oratorios, in cantatas, and in opera. It is distinguished from arias, songs, and other texts serving formal song by not being lyrical. The verse is free—sometimes short, sometimes long—without following a constant meter. This may seem to determine only its external character, but the verse actually prompts the special type of song. |

||

|

[2.4] Indessen ist freylich auch der Inhalt des Recitatives von dem Stoff der Arien und Lieder verschieden. Zwar immer leidenschaftlich, aber nicht in dem gleichen, oder stäten Fluß desselben Tones, sondern mehr abgewechselt, mehr unterbrochen und abgesezt. Man muß sich den leidenschaftlichen Ausdruk in der Arie wie einen langsam oder schnell, sanft oder rauschend, aber gleichförmig fortfließenden Strohm vorstellen, dessen Gang die Musik natürlich abbildet: das Recitativ hingegen kann man sich wie einen Bach vorstellen, der bald stille fortfließt, bald zwischen Steinen durchrauscht, bald über Klippen herabstürzt. In eben demselben Recitativ kommen bisweilen ruhige, blos erzählende Stellen vor; den Augenblik darauf aber heftige und höchstpathetische Stellen. Diese Ungleichheit hat in der Arie nicht statt. |

[3.4] Meanwhile, the content of recitative is certainly different from the material of arias and songs: indeed always passionate, yet not in the equal or continuous flow of the same tone, but rather more alternated, interrupted, and detached. Passionate expression in arias ought to be imagined as a slowly or quickly, gently or rustlingly, yet always steadily forward-flowing stream whose path the music depicts.(59) Recitative, on the other hand, can be imagined as a brook that sometimes flows forth calmly, sometimes rustles between stones, and sometimes crashes over cliffs. From time to time, even within the same recitative, plainly narrating passages occur; and yet in the next moment, fierce and highly pathos-laden passages occur. This diversity does not take place in arias. |

||

|

[2.5] Indessen sollte der völlig gleichgültige Ton im Recitativ gänzlich vermieden werden; weil es ungereimt ist, ganz gleichgültige Sachen in singenden Tönen vorzutragen. Ich habe mich bereits im Artikel Oper weitläuftiger hierüber erkläret, und dort angemerkt, daß kalte Berathschlagungen, und solche Scenen, wo man ohne allen Affekt spricht, gar nicht musicalisch sollten vorgetragen werden. Es ist so gar schon wiedrig, wenn eine völlig kaltsinnige Rede in Versen vorgetragen wird. Und eben deswegen habe ich dort den Vorschlag gethan, zu der Oper, wo durchaus alles musicalisch seyn soll, eine ihr eigene und durchaus leidenschaftliche Behandlung des Stoffs zu wählen, damit das Recitativ nirgend unschiklich werde. Denn welcher Mensch kann sich des Lachens enthalten, wenn, wie in der Opera Cato, die Aufschrift eines Briefes, (Il senato à Catone) singend und mit Harmonie begleitet, gelesen wird? Dergleichen abgeschmaktes Zeug kommt aber nur in zu viel Recitativen vor. |

[3.5] However, a completely indifferent tone should be avoided in recitative because it is absurd to perform completely indifferent matter in singing tones. I have already extensively expounded on this in the article “Opera,” and noted there that cold advice and such scenes where one speaks without any affect should not be delivered in music. It is already very distasteful when an utterly cold-witted speech is delivered in verse. And simply because of this, I gave there the suggestion to choose a unique and thoroughly passionate treatment of the material, so that recitative will never be out of place in opera, where everything should be completely musical. For who can contain their laughter when, as in the opera Catone, the label on a letter “Il senato à Catone” is read by singing and accompanied with harmony? (60) This same tasteless feature occurs, alas, in too many recitatives. |

||

(*) [S., n. 1] S. Dessen Abhandlung über das Recitativ in der Bibliothek der schönen Wissenschaften im XI u. XII Theile. |

[2.6] Wenn ich nun in diesem Artikel dem Tonsezer meine Gedanken über die Behandlung des Recitatives vortragen werde, so schließe ich ausdrüklich solche, die gar nichts leidenschaftliches an sich haben, aus; denn warum sollte man dem Künstler Vorschläge thun, wie er etwas ungereimtes machen könne? Ich seze zum voraus, daß jedes Recitativ und jede [943] einzele Stelle darin so beschaffen sey, daß der, welcher spricht, natürlicher Weise im Affekt spreche. Darum werde ich auch nicht nöthig haben, wie Hr. Scheibe (*) einen Unterschied zwischen dem blos recitirten und declamirten Recitativ zu machen; weil ich das erstere ganz verwerfe. Behauptet es indessen in der Oper, und in der Cantate seinen Plaz, so mag der Dichter sehen, wie er es verantwortet, und der Tonsezer, wie er es behandeln will. Denn hierüber Regeln zu geben, wäre nach meinen Begriffen eben so viel, als einen Dichter zu unterrichten, was für eine Versart er zu wählen habe, um ein Zeitungsblatt in eine Ode zu verwandeln. |

[3.6] Now wherever I will state to composers my thoughts on the treatment of recitative in this article, I will explicitly exclude such things that are entirely dispassionate. For why should you give an artist suggestions as if he could make something unartistic? I require that every recitative and every single passage within it be created so that whoever speaks, speaks affectively in a natural manner. Because of this I also have no need, like Herr Scheibe (*), to make a difference between plainly recited and declaimed recitative; because I entirely discard the first. It may be claimed, however, that it has its place in opera and in cantatas, and so the poet may see how he is responsible for it and the composer how he will handle it. But to give rules concerning this would be, according to my principles, very much like instructing a poet on what type of verse ought to be chosen in order to transform a newspaper into an ode. |

(*) [S., n.1] See his “Abhandlung über das Recitativ” in the Bibliothek der schönen Wissenschaften in parts XI and XII. [M.B.] This is Scheibe 1764–65. |

|

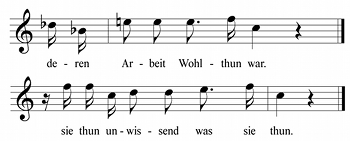

[2.7] Niemand bilde sich ein, daß der Dichter nur die schwächesten und gleichgültigsten Stellen seines Werks dem Recitativ vorbehalte, den stärksten Ausbruch der Leidenschaften aber in Arien, oder andern Gesängen anbringe. Denn gar ofte geschieht das Gegentheil, und muß natürlicher Weise geschehen. Die sehr lebhaften Leidenschaften, Zorn, Verzweiflung, Schmerz, auch Freud und Bewundrung, können, wenn sie auf einen hohen Grad gestiegen sind, selten in Arien natürlich ausgedrukt werden. Denn der Ausdruk solcher Leidenschaften wird alsdenn insgemein ungleich und abgebrochen, welches schlechterdings dem fließenden Wesen des ordentlichen Gesangs zuwieder ist. Man stelle sich vor, Hr. Ramler hätte gegen sein eigenes Gefühl einem Tonsezer zu gefallen, folgende Stelle eines Recitatives, in einem lyrischen Sylbenmaaß gesezt: |

[3.7] No one imagines that the poet reserves only the weakest and coldest passages of his work for recitative, yet applies the strongest outbursts of passions to arias or other songs. For often the very opposite happens and must happen in a natural manner. The most animated passions of rage, doubt, pain, and also joy and admiration, when they have been raised to a high level, are seldom naturally expressed in arias since the expression of such passions thereupon becomes in general uneven and broken off, which in turn is utterly contrary to the flowing essence of proper song. Imagine if Herr Ramler had set the following passage of recitative in a lyrical poetic meter, against his own instinct, to please a composer: |

||

|

Unschuldiger! Gerechter! hauche doch Die matt’ gequälte Seele von dir! –– Wehe! Wehe! Nicht Ketten, Bande nicht, ich sehe Gespizte Keile –– Jesus reicht die Hände dar Die theuren Hände, deren Arbeit Wolthun war. |

Thou innocent, just man! Breathe out thy weak, tormented soul! –– Woe, woe! Neither chains nor ropes, I see Pointed wedges ––Jesus reaches out his hands, His dear hands whose labor was charity.(61) |

||

|

Wie würde doch daraus eine Arie gemacht worden seyn? Es ist wol nicht nöthig, daß ich zeige, wie ungereimt es wäre, eine solche höchstpathetische Stelle, nach Art einer Arie zu sezen. Hieraus aber stehet man deutlich, wie der höchste Grad des Leidenschaftlichen sich gar oft zum Recitativ viel besser, als zur Arie schikt. Wir sehen es deutlich an mancher Ode, nach lyrischen Versarten der Alten, an die sich gewiß kein Tonsezer wagen wird, es sey denn, daß er sie abwechselnd, bald als ein Recitativ bald als Arioso, bald als Arie behandeln könne. |

How could an aria be made from this? It is certainly not necessary for me to point out how absurd it would be to set such a highly pathos-laden passage in the form of an aria. Yet from this it is clearly understood how the highest level of passionate expression is often much better suited for recitative than for aria. We see it clearly in many odes in the lyrical verse forms of the ancients which no composer would dare approach, unless he was able to treat passages alternately, sometimes as recitative, sometimes as arioso, and sometimes as aria. |

||

|

[2.8] Es ist meine Absicht gar nicht hier dem Dichter zu zeigen, wie er das Recitativ behandeln soll. Die Muster, die Ramler gegeben, sagen ihm schon mehr, wenn er Gefühl hat, als ich ihm sagen könnte. |

[3.8] My intention here is not to point out to the poet how he should treat recitative. The model given by Ramler conveys more to the poet, if he has feeling, than I could say to him. |

||

(*) [S., n. 2] S. Oratorium. |

[2.9] Ich will hier nur noch einen besondern Punkt berühren. Ich kann mich nicht enthalten zu gestehen, daß die bisweilen in Recitativen vorkommende Einschaltungen fremder Reden und Sprüche, die der Tonsezer allemal als Arioso vorträgt, nach meiner Empfindung etwas anstößiges haben. Ich habe an einem andern Ort (*) den lyrisch erzählenden Ton des Recitatives in der Ramlerischen Paßion als ein Muster empfohlen. Ich wußte in der That kein schöneres Recitativ zu finden, als gleich das, womit dieses Oratorium anfängt. Was kann pathetischer und für den Tonsezer zum Recitativ erwünschter seyn, als dieses. |

[3.9] I will only touch on one more particular point. I cannot refrain from acknowledging that the interpolation of foreign lines and speeches, which occasionally appear in recitative and which composers always execute as arioso, is somewhat offensive according to my sentiment. I recommended elsewhere (*) the lyrical, narrating tone of the recitatives in the Ramlerian passion. Indeed, I could find no lovelier recitative than precisely the one that begins this oratorio. What can be more pathetic and, for the composer, more desirable for recitative than this? |

(*) [S., n. 2] See “Oratorium.” |

|

–– Bester aller Menschenkinder! Du zagst? du zitterst? gleich dem Sünder Auf den sein Todesurtheil fällt! Ach seht! er sinkt, belastet mit den Missethaten Von einer ganzen Welt. Sein Herz in Arbeit fliegt aus seiner Höhle Sein Schweiß fließt purpurroth die Schläf’ herab. Er ruft: “Betrübt ist meine Seele Bis in den Tod. u.s.f.” |

–– Best of all the children of men! Dost thou hesitate? dost thou tremble? just as the sinner Falls at his judgement! See ye! he sinks, he leaves with the wrongdoings Of an entire world. His heart flies from its cave in labor. His sweat flows deep red from his temples. He cries: “Sorrowful is my soul Until death.” etc. (62) |

||

|

Graun, hat nach dem allgemeinen Gebrauch, der zur Regel geworden ist, die Worte: “Betrübt ist meine Seele” u.s.w. die der Dichter einer fremden Person in den Mund legt, als ein Arioso vorgetragen, und man wird schweerlich, wenn man es für sich betrachtet, etwas schöneres in dieser Art aufzuweisen haben, als dieses Arioso: und dennoch ist es mir immer anstößig gewesen, und bleibt es, so oft ich diese Paßion höre. Es ist mir nicht möglich mich darein zu finden, daß dieselbe recitirende Person, bald in ihrem eigenen, bald in fremden Namen singe. Und doch sehe ich auf der andern Seite nicht, warum eben dieses Dramatische bey dem epischen Dichter mir nicht mißfällt? Wenn mich also mein Gefühl hierüber nicht täuscht; so möchte ich sagen, es gehe an in eines andern Namen, und mit seinen Worten zu sprechen; aber nicht zu singen. Allein, ich getraue mir nicht mein Gefühl hierüber zur Regel anzugeben. Im würklichen Drama, da die Worte: “Betrübt” u.s.f. von der Person selbst, [944] gesungen würden, wär alles, wie der Tonsezer es gemacht hat, vollkommen. Oder wenn es so stünde: |

Graun, according to the common practice which has become a rule, rendered the words “Betrübt ist meine Seele etc.,” which the poet places in the mouth of a foreign person, as an arioso. And you would have trouble, if you looked into it for yourself, to find anything of this sort that is more beautiful than this Arioso. Yet for me, this has always been offensive and it remains so whenever I hear this passion. It is not possible for me to find it plausible that the same reciting person sings sometimes under her own and sometimes under a foreign name. And yet, on the other hand, do I not see why precisely this dramatic device by the epic poet does not displease me? If my senses do not deceive me, then I might say that it concerns speaking in another name and with their words, but not singing. I do not trust my senses alone to declare a rule on this. In true Drama, since the words “Betrübt etc.” would be sung by the person herself, everything would be perfect as the composer did it. Or if it were instead: |

||

|

Sein Schweiß fließt purpurroth, Die Schläf” herab: “Betrübt ist seine Seele Bis in den Tod.” |

His sweat flowed deep red From his temple: “Sorrowful is his soul until death.”(63) |

||

So könnte doch, dünkt mich, das Arioso, so wie Graun es gesezt hat, beybehalten werden. So gar die Folge dieser eingeschalteten Rede könnte hier der Dichter in seinem eigenen Namen sagen. Nur in dem einzigen Vers |

then, I think, the arioso could be kept as Graun wrote it. In fact, the consequence of this inserted line could have the poet speak under his own name. Only in this single verse |

||

| Nimm weg, nimm weg den bittern Kelch von “meinem Munde.” –– | Take away, take away from “my mouth” the bitter chalice.— (64) | ||

müßte seinem stehen. Doch ich will, wie gesagt, hierüber nichts entscheiden: ich sage nur, daß mein Gefühl sich an solche Stellen nie hat gewöhnen können. |