Review of Diane Pecknold and Kristine M. McCusker, eds., Country Boys and Redneck Women: New Essays in Gender and Country Music (University Press of Mississippi, 2016)

Jonathan T. King

KEYWORDS: country music, popular music, social theory, gender, race, class, identity, intersectionality

Copyright © 2017 Society for Music Theory

[1] The significance of gender as a determining musical factor entangled in the web of music analysis has been too commonly overlooked. Adopting gender as a primary starting block can serve as a useful corrective to unintentionally biased contexts when analyzing historical musical literature. It is also a crucial consideration when attempting the difficult theoretical task of interpreting contemporary musical texts, particularly in the production and performance of popular musics. A new anthology by Diane Pecknold and Kristine M. McCusker pushes us to take seriously the intersectionally gendered aspects of aesthetics, composition, genre studies, performance, technology, and reception history of country music. It considers both historical and contemporary music and musicians from these diverse analytical perspectives, with each author’s approach illuminating the others.

[2] Early attempts notwithstanding (notably Bufwack and Oermann’s Finding Her Voice: The Saga of Women in Country Music, first published in 1993), scholarly discourse on country music has been slow to absorb the insights of gender studies. Pecknold and McCusker first sought to redress this analytical lacuna in their 2004 collection A Boy Named Sue: Gender and Country Music. The editors themselves modestly qualified this initial effort as “exploratory” rather than comprehensive. However, the sophistication of concurrent scholarship proved to confirm the early instincts of the editors. Country-music studies expanded beyond the now-canonical historical narrative established by Bill Malone (Malone 1968), still being reinforced in the mid-1990s (e.g., in Dawidoff 1998), to encompass analysis and criticism informed by more recently developed paradigms. These narratives, as David Sanjek noted in his contribution to A Boy Named Sue, emphasized country music’s working-class roots and presented a musical tradition representative of honesty, labor, and resistance—one that, by dint of its straightforward nature, could be restorative or medicinal in its effects (Sanjek, in Pecknold and McCusker 2004, xi). Although the rigor of this early scholarship did much to legitimize this artistic tradition in the eyes of the academy, its reductive paradigm failed to take into account many crucial codeterminants of the country aesthetic. Deconstructing a deeply embedded sociomusical narrative is not easy, of course; sustained intellectual effort and aggressive inquiry are, and will continue to be, necessary.

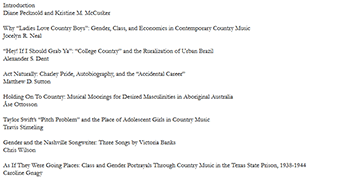

Example 1. Table of Contents

(click to enlarge and see the rest)

[3] With the present volume, Pecknold and McCusker have mobilized much new scholarly effort and inquiry toward this aim. One goal of this second collection is shared with the first: to demonstrate that gender is not only an interesting but a necessary analytical framework. They have extended their earlier anthological work by collecting 12 essays (Example 1) that are cognizant of the greatly expanded body of scholarship that has emerged since their first collection. (A useful selected bibliography of this more recent work is included in this new book.) This work sharpens the analytical focus through another set of specific case studies, and is clearly articulated toward the end of Country Boys and Redneck Women by Georgia Christgau. She offers a perceptive illumination of the cross-pollinating work of gender and class in the reception of Kitty Wells’s “It Wasn’t God Who Made Honky Tonk Angels.” As public perceptions of her changed dramatically, Wells’s own subdued reaction to the song’s incredible success allowed for many interpretive ambiguities over time. The shifting reassessments of Wells’s integrity and authenticity delineated by Christgau reveal the difficulties inherent in popular-music analysis. Her essay clearly demonstrates the need for mutable analytical frames that can take these contingencies into account. The collected essays judiciously chosen by Pecknold and McCusker offer many such frames.

[4] A more trenchant goal of Pecknold and McCusker’s new effort is to productively problematize the intersectionality of gender with other socially maintained interpretive and expressive frames such as race, and class, and authenticity. Class and authenticity have long been hallmarks of country-music scholarship (as noted above), commonly overdetermining much of the narrative. This volume complicates their significance by foregrounding gender; specific case studies demonstrate that gendered concepts are tightly intertwined with, and even constitutive of, class and authenticity issues.

[5] To this end, Jocelyn R. Neal interrogates why “Ladies Love Country Boys” (the title of a hit single released by Trace Adkins in 2006) in terms of the intersection of gender, class and economics. She asks what this musico-cultural moment in contemporary country music may have to say about the music’s fan base in the first decade or so of the 21st century. She examines a set of country tunes released between 2008 and 2012, each of which presents aspects of the “good ol’ boy” persona (3), and offers a rich and polysemous assessment of the purportedly “rural” imagery deployed in these songs. She caps the essay with a rich and layered analysis of Justin Moore’s 2007 song “Bait a Hook” (and its accompanying video) that traces shifting tokens of rustic authenticity over the course of the song. In the video, a surprising sequence of narrative shifts leaves listeners and viewers with radically different understandings of the singer’s authenticity depending on their own experience of “country life.” Neal’s close reading both confirms and extends the argument of the chapter: that both artists and audiences continually recontexutalize these terms, thereby altering their meanings. This exemplifies the best kind of popular-music analysis, both culturally contexualized and rooted in practice.

[6] Recently, the role of race in country-music history has been highlighted in another anthology curated by Pecknold, the essential Hidden in the Mix: The African American Presence in Country Music. Pecknold’s own contribution to Country Boys and Redneck Women makes intersectionality historically explicit in a race-sensitive comparison of two seemingly contrasting women, Linda Martell and Jeanne C. Reilly, whose career trajectories challenge many common race-, class-, and gender-based assumptions. She shows how these musicians worked against ideologies of their time, demonstrating how the “practice” of country musicians can and does affect “theory”—a larger aim of the anthology. In light of this book, it is hard to imagine any convincing class- and race-based, commodified, constructed, contained, or queer readings of either “country classics” or contemporary country performance without such a deeply felt and societally conditioned framework of gender.

[7] The increased sophistication of research in masculinity studies since Pecknold and McCusker’s last edited volume allows for a more expansive reading of the significance of gender and a renewed critique of concepts understood to be masculine. Matthew D. Sutton’s reading of African-American country star Charley Pride’s autobiography highlights the carefully drawn links between race and masculinity in the country music universe. In his own story, Pride carefully avoids presenting himself as too ambitious or driven, suppressing purportedly masculine characteristics in a racially fraught context. Sutton’s dismantling of Pride’s rhetorical “naturalness” demonstrates how careful attention to marked and unmarked expressive gestures can work to challenge and overturn interpretive norms, thereby pushing analytical theory forward.

[8] This collection also probes the cross-cultural difficulties of gender and the possibilities for using it as an analytical frame. Åse Ottosson describes how Aboriginal Australians cling to the residual aesthetic norms of country music in order to frame their own emergent masculinities. His account, which untangles “aboriginal” and “country” concepts of masculinity, demonstrates the interpretive subtlety required when encountering such intercultural appropriation. Analogously, Alexander S. Dent explores the growing significance of a rurally coded masculinity in urban Brazil, which is shifting the poetics of contemporary música serteneja, or “college country.” The emergence of this “formulaic” country genre in a cosmopolitan context has created anxiety among some Brazilians who fear the implications of potentially embarrassing intercultural readings of these songs. The relationship between form and content is quite fraught in both of these examples, and cross-culturally gendered assumptions are at the heart of these analytical conundrums.

[9] Political implications of gender are introduced quite explicitly by Caroline Gnagy, who describes a group of convicted women in the 1930s and 1940s who were able to creatively reframe themselves as an all-female country group. These women were able to use the resources of the political institution that imprisoned them to harness the gendered musical tropes and cultural stereotypes of the “outside world,” rehabilitating and transforming their individual identities during their incarceration. The fact that country performance was generally abandoned by these women upon their release demonstrates the functional nature of these “country” performances, which took place in hyperdetermined social conditions, and compels a listener or analyst to carefully reconsider the significance of every note. The performances were effective social tools, their syntactic and symbolic significance indelibly imbued by the circumstances of their articulation.

[10] Hyperdetermined, marked, expressive musical patterns become institutionalized in contemporary production and performance as well. In an examination of Victoria Banks’s Nashville-based songwriting, Chris Wilson usefully describes different understandings of what a “songwriter” is: a creative individual, a laborer, a community member, and/or a cowriter. By unpacking gendered tropes and assumptions that affect or even determine many compositional decisions in Banks’s songwriting, Wilson shows that the gender of the artist influences or shapes these different understandings of “songwriter.” This, then, must transform our understanding of their creative output. The careful treatment of these clichés and assumptions allows a song to represent more than simply the subject-position of its songwriter, and thus changes the object of analysis. His account reveals the complex songwriting process that generates these “artless” works, and demonstrates that analysis might be applied just as productively to the songwriting process as to the finished product.

[11] Travis Stimeling usefully distinguishes between the authorial voice and the singing voice, tracking the trope of “bad singing” as an injurious critique directed at a well-known young female musician, Taylor Swift, in commercial and social media forums. How, he asks, can someone with ostensibly flawed technique achieve such widespread success? Among his provocative suggestions is the proposal that the pitch problems caused by lack of vocal support are envoiced markers of girlhood that inspire Swift’s most enthusiastic fans—perhaps analogous to the “cry-break” that allows the covert expression of emotion in the male singing voice. This account uncovers the gendered and age-based assumptions commonly embedded in country’s authenticity tropes. Stimeling concludes that the harsh online critiques of this singer might belie the fact that a voice of determined, aspirational integrity may be emanating from an apparently unlikely source.

[12] Nadine Hubbs examines the songwriting process as she carefully unpacks “Redneck Woman” by Gretchen Wilson. As Wilson reinscribes the term “redneck” with an unexpected gender (comparable to “female plumber”), this song alternately aligns itself with and deviates from the tightly stylized signifiers of contemporary country music performance practice, leveraging class-based assumptions in order to transform gendered ones. Hubbs suggests that this may be a mixed blessing—as class conflicts are too easily and commonly displaced onto gender conflicts—and that the song may ultimately be hurting, not helping, the plight of its fans. Yet she allows for the possibility that, through the creative articulation of its seemingly contrived symbolism, the song may work as a powerful (and anti-bourgeois) bid for solidarity and cultural authority.

[13] Kate Heidemann demonstrates how strikingly distinct presentations of the feminine can each be commercially viable. Loretta Lynn’s bold imposition on urban masculinity and Dolly Parton’s strategic deployment of rural femininity demonstrate the rich expressive possibilities within gendered constraints, even as they continue to trade in standard tropes of rural, working-class authenticity. Heidemann analyzes lyrics, vocal performance, instrumental accompaniment, biography, and persona in turn, comparing and contrasting these two legendary approaches by wisely grounding her argument in specifics. The expressive power of these overlapping sets of signifiers are certainly not lost on performers themselves, as Leigh Edwards demonstrates in her own essay on Dolly Parton’s tactical manipulation of class and gendered tropes. Parton described how she combined an adolescent admiration of local prostitutes’ apparent glamour with a deliberate projection of purity and innocence, channeling these complexities through knowing, campy performance. In Edwards’s interpretation, Parton confronts common feminine stereotypes, critiquing them through her complex, shifting embodiment of them. Edwards’s concluding remarks could serve as an epigraph for the entire collection, noting that in Parton’s performance, gender is not merely “a set of socially constructed practices and behaviors . . . but is deeply contextualized in terms of country music themes and history” (207); without these themes and history, the performance makes much less sense.

[14] The essays in this book, greatly informed by gender studies and historical scholarship, would work well as an addition or corrective to other music-theoretical approaches that privilege decontextualized sonic parameters, both historically and contemporaneously. Productive comparisons abound, since many of the essays partially overlap in either content or approach. One might ask students to analyze the varied songwriting approaches of Victoria Banks, Taylor Swift, and Gretchen Wilson; or compare examples of country music “out-of-place” in Australia, Brazil, and a Texas state penitentiary. Students might ask how the gendered African-American experiences of both Charley Pride and Linda Martell are articulated acoustically. From a wider theoretical standpoint, they might juxtapose Heidemann’s and Edwards’s differing but complementary accounts of Dolly Parton’s active construction of her own identity; or they might engage with Neal’s, Christgau’s, and Hubbs’s bookending essays linking different “countrys” to their particular cultural moments, considering how gender inextricably connects an ever-changing genre to the society that produces and consumes it. Each of these assignments would require a student to articulate explicitly what data are analytically relevant—no easy task.

[15] Country Boys and Redneck Women extends the scope and range of its 2004 predecessor, intersecting with and illuminating other critical and analytical approaches in ways that can enlighten all scholars of popular musics. How each of these artists and artworks participates in the genres called “country” affects the criteria that an analyst chooses to consider. Each essay in the collection thereby presents an opportunity to revisit and rethink an analytical framework, using gender as a useful starting point. Taken as a set, they compel us to confront what David Brackett has called the musicological quagmire: what “guarantees the ‘fit’ between the song, the audience, and the analytical discourse” (Brackett 1995, 20). This quagmire needs to be continually negotiated as decades pass. As such, this outstanding anthology (along with its predecessor, A Boy Named Sue) is a welcome contribution, and will continue to be valuable as a marker of the emergent state of music scholarship.

Jonathan T. King

107D Lipinsky Hall, CPO #2290

Music Department

University of North Carolina – Asheville

1 University Heights

Asheville, NC 28804-8510

jking6@unca.edu

Works Cited

Brackett, David. 1995. Interpreting Popular Music. Cambridge University Press.

Bufwack, Mary A., and Robert K. Oermann, eds. 2003. Finding Her Voice: Women in Country Music, 1800–2000. Country Music Foundation Press and Vanderbilt University Press. (Orig. pub. 1993 as Finding Her Voice: The Saga of Women in Country Music.)

Dawidoff, Nicholas. 1998. In the Country of Country: A Journey to the Roots of American Music. Random House.

Malone, Bill C. 1968. Country Music, U.S.A. University of Texas Press.

—————, ed. 2013. Hidden in the Mix: The African American Presence of Country Music. Duke University Press.

Pecknold, Diane, and Kristine M. McCusker, eds. 2004. A Boy Named Sue: Gender and Country Music. University Press of Mississippi.

Stone, Ruth M. 2008. Theory for Ethnomusicology. Pearson Prentice Hall.

Copyright Statement

Copyright © 2017 by the Society for Music Theory. All rights reserved.

[1] Copyrights for individual items published in Music Theory Online (MTO) are held by their authors. Items appearing in MTO may be saved and stored in electronic or paper form, and may be shared among individuals for purposes of scholarly research or discussion, but may not be republished in any form, electronic or print, without prior, written permission from the author(s), and advance notification of the editors of MTO.

[2] Any redistributed form of items published in MTO must include the following information in a form appropriate to the medium in which the items are to appear:

This item appeared in Music Theory Online in [VOLUME #, ISSUE #] on [DAY/MONTH/YEAR]. It was authored by [FULL NAME, EMAIL ADDRESS], with whose written permission it is reprinted here.

[3] Libraries may archive issues of MTO in electronic or paper form for public access so long as each issue is stored in its entirety, and no access fee is charged. Exceptions to these requirements must be approved in writing by the editors of MTO, who will act in accordance with the decisions of the Society for Music Theory.

This document and all portions thereof are protected by U.S. and international copyright laws. Material contained herein may be copied and/or distributed for research purposes only.

Prepared by Brent Yorgason, Managing Editor

Number of visits:

5368