Chasing the Phantom: Features of a Supracultural New Music *

Michael Tenzer

KEYWORDS: contemporary music, cross-cultural influence, Balinese gamelan, Dewa Ketut Alit

ABSTRACT: Balinese composer Dewa Alit (b. 1973) splits his time between home and abroad, absorbing many kinds of music. His latest gamelan work (2016) is Ngejuk Memedi, from the Balinese ngejuk, to chase, and memedi, a feared phantom of the Balinese unseen world that takes human form. It animates his evolving desire for a “broader conception of what gamelan is, one based on its relationship to other cultures” (Alit in Tenzer 2011, 134), while submitting to the phantom-like elusiveness of the goal. In analyzing part of Ngejuk Memedi, this article argues for an emergent musical supra-culturalism embedded in innovative rhythmic practices. In Alit’s case, three strata of metrically dissonant parts are superposed in a continually changing relationship. His procedures are suggestive of those of other contemporary musicians from around the globe, whose kinship with Alit comes into focus once one delimits the intellectual and aesthetic desiderata they have challenged themselves to explore. Often notated by composers but transmitted and performed orally, such music is highly conceptual but deeply embodied in felt groove. Its signature element is the juxtaposition or layering of complex, asymmetrical periodicities that are rare or unknown in source traditions, but trace to ideas circulating from African, Indian, Western and other art musics that have become common currency. In these intersecting senses, they comprise a new phenomenon.

Copyright © 2018 Society for Music Theory

[1] In 1992, Perspectives of New Music published John Rahn’s interview with sitar maestro Imrat Khan, who said:

We are living in a very beautiful world today. These cultures developed in the West and the East

. . . in such a beautiful way—in a closed environment, with the knowledge accumulated like matured wine. . . So it is very nice that like this mature wine that has been cultivated and matured for such a long time in one environment, suddenly it is available! And it is beautiful. It is available because of television and radio and planes—which were not there before—and recording, especially. . . We are living in a world where all this fantastic contribution of thousands of years and the work of masters is available to us (Rahn and Khan 1992, 127).

[2] From a 2017 perspective, Khan comes off as both passionate and quaint, since he was speaking before the internet, before a lot of things. 1992 was a long time ago. In terms of cultural interaction, 2017 maps to 1992 as 1992 maps to 1950, or maybe 1850 or 1750. Khan also sounds magnanimous, but what resonates now is how instinctively he, an Asian traditional musician, asserts his own agency in the process of cultural mixing. Wine is an import to India just as raga is to the West, so his choice of that metaphor slyly highlights how free he feels to access the world of music. Today it is common to celebrate how musics mingle, although the recent increase in both depth and intensity of exchange of which Khan spoke is not to be taken for granted. The idea that agency has always been multidirectional, though, is, I think, like all cultural diversity issues, something that is still sinking in.

Example 1. Dewa Ketut Alit www.dewaalitsalukat.com

(click to enlarge)

[3] Consider the life and musical mind of someone younger than Imrat Khan, the Balinese composer Dewa Ketut Alit (Example 1). Born in 1973, Alit came to musical maturity around twenty years ago and hence has had some decades to drink the wine Khan extolled. Intensely self-aware, he has been around the block as much as any musician today, listening raptly to everything, travelling, teaching, and performing abroad. He works in a small, vibrant community of other Balinese composers and their expanding international connections. Alit completed a commission for Frankfurt’s Ensemble Modern in 2015 but, though now experienced with Western instrumentation and notation, his medium remains the gamelan just as the piano was Chopin’s.(1) Some musical consequences of Alit’s agency are evident in the following discussion of tuning system and rhythm in a composition from 2016.

[4] Later, I generalize the analysis to argue that Alit’s music, while exemplary in Bali, shares the effects of Imrat Khan’s wine with other new musics elsewhere in the world. He composes textures both new and conspecific to others produced by musicians of his ilk at work today in many countries. Not via quote or allusion, as it might have been in an earlier era, but with ideas based in different traditions and now circulating widely, that are transformed in the warp and weft of the structure such that analysis is needed to isolate and describe the sensations produced. In its quest for new structures and aesthetics, there is nothing wrong with calling such music art music. But the fusions I describe crucially rely on oral tradition, where musical action coalesces around the shared aural experience of performance interaction and groove. A key achievement of such art music is to synchronize bodies and stretch their capacities in new kinds of groove.

Dewa Ketut Alit

Example 2. Map of Bali showing Pengosekan

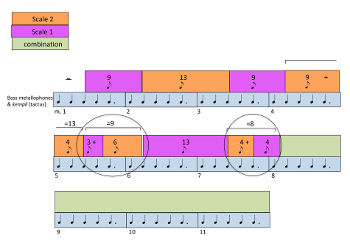

(click to enlarge)

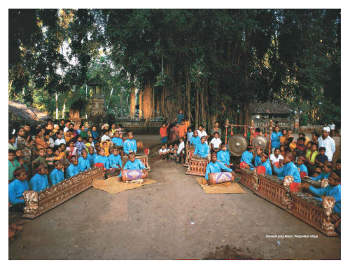

Example 3. Gamelan ensemble, Pengosekan village, 1971

(click to enlarge)

Example 4. A version of pélog (saih pitu)

(click to enlarge)

Example 5. Video recording of the scale

(click to watch)

[5] Speaking to this distinguished audience, I’m sensitive to how Balinese gamelan music remains strange to many of our best musical minds. It is iconic, which ironically makes it susceptible to pigeonholing. But the statute on the Orientalist clichés of gamelan as static, timeless, and devoid of climax is long expired, leaving a gap. Plus, 40 years of experience teach me that to outsiders it can be overcomplicated and grating. I assume, maybe wrongly or defensively, that most of you have never considered a Balinese piece down to its bones, having never been coached nor asked to. So, I offer a helping hand. I also present Alit as someone who merits your attention—not as an essentialized Balinese, for crying out loud, but as an ambitious composer with striking ideas. The idea of any gatekeeping restricting analysis of his music to members of some cultural insider’s club is also cliché. Not that his roots are of no consequence, of course.

[6] Alit is from Pengosekan, a town in south-central Bali known for fecundity in music, visual arts, and puppet theater (Example 2). In Example 3’s 1971 photo, the village gamelan collective is pictured around the village square; Alit’s father is the drummer on the right. Artistry is in his bloodline, and Alit is third of four brothers all steeped in gamelan. My first visit to Pengosekan was in 1977, and I have known Alit since 1987, when he was 14 and I was 30. Together we obsessed on composing gamelan music; his interactions with me and many other foreigners helped shape all who were part of the growing international Balinese gamelan community. Also in this period Balinese grew disgusted with the straightjacket of Indonesian President Suharto’s so-called New Order, whose static and officious ideology of traditional culture made people ache for release. In the influential but moribund government, music academy students—Alit among them—rebelled. Composers groped for ways to move beyond imposed traditional forms, while in 1998 a political revolution at last felled Suharto’s corrupt regime. Now the social and musical pieces were in place, and Alit was poised to develop gamelan not insularly but according to a “broader conception of what gamelan is, one based on its relationship to other cultures” (Alit in Tenzer 2011, 134). Alit has many Balinese composer peers, but his music stands out.(2)

[7] The instruments in the photo played music in the dominant kebyar style, rooted in centuries of anonymously-composed repertoire that functioned for court and temple rituals (Tenzer 2000). Using a five-tone scale, its repertoire was structured around a set of inherited gong cycle patterns, nearly all of which had beat counts in powers of two. This music is most efficiently characterized as heterophonic, with rhythmically and registrally stratified orchestral layers that align on the same scale tone at regular metric accents. Irregularities abound, generated from drumming, dance, tempo, or melodic factors, but mainly in the frame of the gong cycles’ fixed lengths. Even with only five tones, pitch can nonetheless sound complex because of the tuning, in which instrument pairs are intentionally tuned far enough apart to acoustically beat at about 8 cycles per second when paired tones are struck. To this concoction add the spectral spray of hard mallets rapidly striking bronze keys, and the use of bamboo flutes that wander outside the scale.

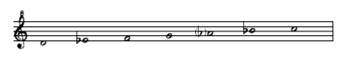

[8] The five-tone scale is a modal extraction from the parent seven-tone scale widely known as pélog (actually its Javanese name), or, as was originally known in Bali, saih pitu (series of seven). In relative disuse in 1971, the parent scale was, in a watershed moment, revived in the 1980s. In his early compositions Alit used a gamelan tuned to something close to the scale shown in Examples 4 and 5 which, like all Balinese tunings is not standardized but lies within norms. The approximate notation represents neither the intervals nor the paired tuning.

[9] Alit formulated a critique of tradition: the compositional means of previous generations were priceless but overdetermined, their expressivity exhausted from coopting and tainting by the political order. As he saw it, a core musical Balineseness required rescue from its official defenders. Key nonnegotiable features had to be preserved: the sociality of gamelan oral learning and notation-less performance, the basic physical gestures of playing techniques and ensemble interaction, and the signature intimacy of Bali’s ingenious interlocking rhythms. Everything else—especially musical forms and tunings and their compositional implications—needed reconceptualization “in relation to other traditions.”

Chasing the Phantom

Example 6. Memedi, as imagined by painter Ketut Budiana, Padang Tegal village, Bali (repoduced with permission)

(click to enlarge)

Example 7. Alit’s 11-tone scale system

(click to enlarge and listen)

[10] For this Alit had a full set of gamelan instruments built to his specifications, set it up in his home studio, and called players together. He named the instrument set (and the collective musical organization structured around it) Gamelan Salukat, the latter word signifying a home or a place for creative regeneration; and he began to conceive a series of new compositions for it that exploited his crystallizing concepts. The series (and the piece I will analyze) is called Ngejuk Memedi, from ngejuk, to chase, and memedi, a phantom creature of the unseen world, told of in Balinese folktales, that takes grotesque human form. Most Balinese believe memedi exist, but there haven’t been any sightings (Example 6). Alit makes the metaphor explicit—he is chasing an unseen, unknown, uncapturable musical fusion. Each composition is thus like a folktale. I will show an extended video excerpt of the piece in a moment.

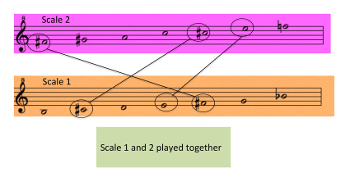

[11] Alit reconceived scale and tuning in his new gamelan. After the 12-note chromaticism of his piece for Ensemble Modern, with the Western scale ringing in his ears, he invented, following his taste but with reference to twelve-tone equal temperament, a hybrid collection of eleven tones (Example 7). These are distributed among two overlapping seven-tone collections that share three tones but not the other four (3 + 4 + 4 = 11). Call them Scales 1 and 2. They differ in how they slice up the octave, and they retain the acoustic beating of Balinese paired tuning. Half of the instruments in the gamelan are tuned to scale 1, and half to scale 2. In the music, Alit uses the scales both in juxtaposition and in combination. As the recordings demonstrate, both the intervals within each scale, and the vertical ones resulting from superposition of the tones of one or both of scales 1 and 2, are of diverse sizes. Alit eschews the heterophonic principles of traditional gamelan to explore the intervals’ vertical combinations, so that various kinds of chords, rather than scale tone unisons and octaves, now appear on the vertical axis. And whereas other gamelan have only one or two deep gongs, Alit (at great personal financial expense) includes one for each tone of Scale 1, which includes of course the three tones shared with Scale 2. Alit gives them a richer role as a bassline, supporting melodic tones above. Freed from tolling at regular fixed time intervals, the gongs act as independent contrapuntal agents, thus weakening the whole premise of cycles. A further consequence in Alit’s music is that phrase boundaries in different textural layers are only sometimes coordinated. The overlapping makes points of full ensemble articulation rarer, driven by compositional design rather than expected periodicity.

Example 8. Page one of Alit’s score

(click to enlarge)

Example 9. Ngejeuk Memedi Macroform

(click to enlarge)

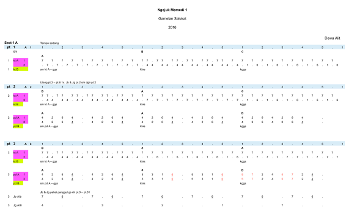

[12] Placing this in a recent context, repetition in contemporary Balinese music has become less pervasive in the past few decades. Musicians’ capacity to memorize extended, multi-part, largely through-composed pieces has upped dramatically. The complexity has led many composers to begin to use a cipher notation, albeit in sketch form, because the different parts in the music are not as determined by a common practice as they were before. This thinking gradually gestated more extensive compositional imagination and drove Alit to fully notate his music in a cipher notation score. As in the history of Western music, this becomes a feedback system accelerating innovation and complexifying form. Example 8 shows three systems on the first page of the Ngejuk Memedi score. Ciphers 1 to 7 indicate pitches in each of the two overlapping seven-tone sets, and the one to which a cipher refers is indicated by purple or light green on the left. The tactus, its metric groupings (on this page, a 5-beat meter), and its subdivisions are given in the light blue strip.

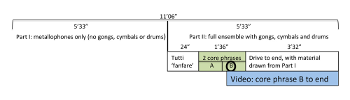

[13] Now to the music; I start from the macroform and zoom in to a small segment to theorize a single moment in it. Alit splits the macroform in two equal and contrasting halves by using only metallophones (comprising about half the ensemble) in the first part, and reserving the arsenal of the full gamelan—including gongs, cymbals, and drums—for the second (Example 9). After a kind of tutti fanfare at the midpoint where the latter group of instruments enters, a pair of striking phrases ensues (call them core phrases A and B). They are the experiential bull’s eye of the piece, analogous to a Bartók Fibonacci moment or the point of furthest harmonic remove in a sonata form development. In these two phrases, the scale’s cardinality of eleven is generalized to determine the meter: 11 beats with a non-isochronous tactus (that I write as four quarters plus a dotted quarter)—as well as the number of iterations of the meter, also 11. Hence core phrases A and B comprise a balanced, contrasting pair of 11 measures each. A drive to the end follows, featuring transformations of earlier material. The length of the whole is, maybe intentionally, just about 11 minutes. The video in Example 11 starts from Core Phrase B and continues for 4 minutes, to the end of the composition.

|

Example 10. Screenshot of kempli player and his 11/8 meter (click to enlarge) |

Example 11. Video of Gamelan Salukat Musicians in Rehearsal: Core Phrase B to end (click to watch) |

Example 12. Core Phrase B grouping structure

(click to enlarge and listen)

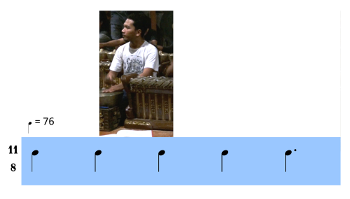

[14] Example 10’s video screenshot shows the player of the small gong kempli who orients the group in the meter. At the beginning of the video and for some time thereafter, you can follow him playing the

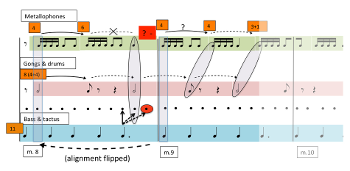

[15] Now consider the 11 measures of core phrase B (Example 12). In this representation, the tactus and the bass metallophones are shown in light blue; the bass metallophones play on the downbeat of each measure and a few other times. The rest of the instruments are shown in contrasting colors, reflecting juxtapositions of groups using scales 1 and 2. The inter-onset times of these groups alternate between 9 and 13 beats, offset from the beginning of the

Example 13. Core Phrase B mm. 8–11, staff notation

(click to enlarge and listen)

Example 14. Core Phrase B, grouping structure of mm. 8–10, paradigmatic layout

(click to enlarge and listen)

Example 15. Core Phrase B, grouping structure of mm. 8–10, linear layout

(click to enlarge and listen)

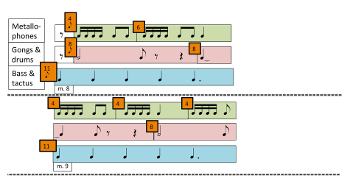

[16] Example 13 zooms into this long passage—measures 8–11 of Core Phrase B—to consider its subgroups. In this staff transcription, we see the three textural layers of the phrase: high metallophones; a set of nine gongs (large and small) played as a stacked chord and reinforced with drum patterns; and the continuing bass metallophones and little kempli tactus. The high metallophones play a set of short groups of similar but varying lengths and twisting melodic contours. They are hocketed, the two parts shown with stems in reverse directions. The long horizontal gong row, with four players sounding eight gongs as a chord, punctuates sparsely. The two layers’ combined quality creates a very distinctive rhythmic sensation, especially at the final dotted-quarter beat in each measure.

[17] In Example 14 these measures are vertically aligned for paradigmatic comparison. The gong-and-drum layer begins after an eighth rest and has a period of 8 eighth-note beats. Four statements of this group fill the remaining 32 beats of measures 8–10. The chord is struck at the beginning and followed by a rim stroke after four beats. Naturally these grouping periods are dissonant with the

[18] The hocketing, high metallophone layer also begins after an eighth rest and comprises 8 brief groups of 4, 6 or 3 eighths; there is no system to their ordering and the group boundaries never coincide with the other layers except at the beginning and at measure 11, the placid final bar of Core Phrase B, a rare moment of pause.

[19] In Example 15’s view of measures 8–10, I add a row of dots to calibrate the pulsation. The tilting, teetering—and, I think, novel—rhythmic experience engendered by the three desynchronized layers is the heart of the matter. Of course, the 11-beat meter is a primary orientation, and since both of the other layers have groups with even numbers of beats, their alignment with respect to the tactus flips in each bar. That is a phenomenon felt in music of many kinds, notably Indian music, where layering of meter and repeating groups—one each with an odd count and an even count, moving in and out of alignment with one another—is a signature technique. In Indian music, though, drumming and melody layers may clash with the tactus, but they always coordinate with one another. Thus the salient feature with Alit is the presence of the independent third layer. The interaction of the two even-count layers with each other and with the odd-count tactus is most potent at the end of the measure, when the tactus lengthens to a dotted-quarter. Each time this dotted quarter wheels back around like a big searchlight, it pulls the actions of whatever agents are caught in its beam into the light, lurching them off their footing and into suspense.

[20] For instance, one can project a repetition of the initial four-beat group in the metallophones when their next group starts with an identical rhythm. But the group length is not replicated; it extends to six beats. At the moment we perceive the projection as unfulfilled, we are perched on the second eighth of the tactus’s dotted quarter beat; when this floats to its third eighth, we are weightless for a moment, then tumble. The next metallophone group catches us securely on the downbeat, its position flipped from the previous bar. But we are still recovering from the hovering. As the next measure begins we don’t know what to project. Once we realize that the group has shrunk back to its original size, there is hope for a foothold.

[21] Meanwhile the gong-and-drum layer unfolds its eight beat groups, each bisected by the rim stroke. When the second of these groups begins, it is just at the moment when we understand that the second group of the metallophone layer is going to extend. On the one hand, it reinforces that moment and the pendulum of weightlessness that follows; on the other, it has its own quality of restarting. And a moment later, when the metallophones reenter, the gongs are still sounding. With the gongs’ rim shot on the second tactus of measure 9, they realign with respect to measure 8, as did the metallophones. But by this time, they themselves have strayed by two additional beats from the metallophones because of the latter’s extended second group.

[22] The third layer thus ups the ante and elicits novel sensations. With focus we readily perceive them; no line of excessive complexity has been crossed, but our senses are stretched. In the context of Alit’s composition, Core Phrase B is but one of many such passages permeating his language. I am not making an obtuse claim such as that music in three parts is itself something new. Nor that metric dissonance and non-isochronous meters are novel. But here is what I do claim.

New Music and Groove

Example 16. Features of a Supracultural New Music

(click to enlarge)

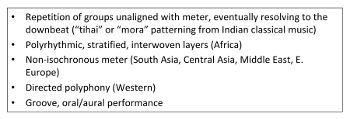

[23] Alit has assimilated a range of musical techniques issuing from music traditions to which he has listened and, in some cases, studied a bit, or at least contemplated as deeply as his circumstances and his impressive ears and imagination permit. Example 16 shows the most iconic of these techniques, circulating like Imrat Khan’s wine, among connoisseurs, to Alit, or to many of us in this room or all over the world: the metrically dissonant repeating rhythm groups of Indian classical music (mentioned earlier) that resolve to a future downbeat; the stratified interwoven polyrhythm layers of West African drumming and the Afro-diaspora; the non-isochronous meters of South and West Asia and Eastern Europe; the directed polyphonic spans of Western art music. Their impact, however full, partial or selective, is nevertheless insufficient. The linchpin of this kind of supracultural new art music, as I suggested earlier, is the performers’ complicity in new kinds of embodied groove. The performers must deeply feel—without notation and with physical fealty to a collective conception of the music’s organization—the arithmetically extended and multidimensional rhythmic pushes and pulls of this music. This is also why we are speaking here of something distinct from related rhythm features that can be found in some Western music performed from notation, such as in works of John Adams or Bartók or going back further to Brahms and more. The particular kinds of rhythm combination in Alit's music, and groove that binds them, can only be realized through a collectivity that to some degree alters the sense of the composer’s absolute authorship.

[24] Alit’s conception of how the techniques can blend is sometimes superficial, sometimes canny, always flexible—that is innovation happening. He has many peers. In Salvador, Brazil, composer Letieres Leite leads the Rumpilezz jazz big band, augmented with an Africa-derived rhythm section. His music works with transforming West African time lines from twelve or sixteen beats to sevens or nines (Diaz 2017). Progressive improvisers in New York—Rudresh Mahanthappa, Vijay Iyer, Steve Lehman, Tyshawm Sorey to name just a handful—have inquired into Indian and African music deeply. Israeli bassist Avishai Cohen structures many of his most confounding grooves on the conflict between odd-cross rhythms and even meters. So does Radiohead (Hesselink 2013).

[25] These musics are connected by common structural interests. They are also connected to new music that is played from notation. In college I never imagined, during countless lights-out sessions absorbed in Conlon Nancarrow’s music, that people would one day play it, as groups like Bang on a Can and Alarm Will Sound do with finesse now. Nor could I have remotely foreseen, when I first went to Bali, that I would one day give the report I just gave. Human bodies are pushing their capacities to coordinate in rhythm, and the advance has been rapid. The change may tap into latent abilities, or genuine evolution might be afoot. Music theorists, in any case, will have no shortage of questions to investigate, and to toast this let’s uncork a bottle of Chateau Imrat Khan, vintage 1992.

Michael Tenzer

University of British Columbia

http://www.michaeltenzer.com

michael.tenzer@ubc.ca

Works Cited

Diaz, Juan Diego. 2017. “Experiments with Timelines in Afro-Bahian Jazz: A Strategy of Rhythmic Complication.” Analytical Approaches to World Music 6 (1).

Hesselink, Nathan. 2013. “Radiohead’s ‘Pyramid Song’: Ambiguity, Rhythm, and Participation.” Music Theory Online 19 (1). http://mtosmt.org/issues/mto.13.19.1/mto.13.19.1.hesselink.html

Hough. Brett. 1999. “Education for the Performing Arts: Contesting and Mediating Identity in Contemporary Bali.” In Staying Local in the Global Village: Bali in the Twentieth Century, edited by Raechelle Rubinstein and Linda H. Connor, 155–80. University of Hawai’i Press.

McGraw, Andrew. 2013. Radical Traditions: Reimagining Culture in Balinese Contemporary Music. Oxford University Press.

Rahn, John, and Ustad Imrat Khan. 1992. “An Interview wih Ustad Imrat Khan.” Perspectives of New Music, 30 (2): 126–45.

Steele, Peter M. 2013. Balinese Hybridities: Balinese Music as Global Phenomena. PhD diss., Wesleyan University.

Tenzer, Michael. 2000. Gamelan Gong Kebyar: The Art of Twentieth Century Balinese Music. University of Chicago Press.

—————. 2011. Balinese Gamelan Music. Periplus Editions.

Vickers, Adrian, ed. 1996. Being Modern in Bali: Image and Change. Yale University Southeast Asia Studies, Monograph 43. Edited by A. Vickers. Yale.

Vitale, Wayne. 2002. “Balinese Kebyar Music Breaks the Five-Tone Barrier: New Composition for Seven-Tone Gamelan.” Perspectives of New Music 40 (1): 5–69.

Footnotes

* Finding Alit’s Music

CDs of Alit’s music are available on his website, http://www.dewaalitsalukat.com.

See also http://vitalreco rds.ws/about for the CD Çudamani: The Seven-Tone Gamelan Orchestra from the Village of Pengosekan, Bali, which contains Alit’s early works Geregel and Pengastung Kara.

Return to text

CDs of Alit’s music are available on his website, http://www.dewaalitsalukat.com. See also http://vitalreco rds.ws/about for the CD Çudamani: The Seven-Tone Gamelan Orchestra from the Village of Pengosekan, Bali, which contains Alit’s early works Geregel and Pengastung Kara.

1. Alit’s Open My Door was premiered by Ensemble Modern in Frankfurt on October 6–7, 2015, as part of their Ruang Suara—Contemporary Music from Indonesia project.

Return to text

2. For sweeping insight into Balinese history, including its conditions during the Suharto years, see Vickers 1996. On the Balinese Arts Academy and its ideological contestations, see Hough 1999. An invaluable study of contemporary music in Bali is McGraw 2013. Vitale 2002 and Steele 2013 discuss some of Alit’s earlier compositions in considerable depth.

Return to text

Copyright Statement

Copyright © 2018 by the Society for Music Theory. All rights reserved.

[1] Copyrights for individual items published in Music Theory Online (MTO) are held by their authors. Items appearing in MTO may be saved and stored in electronic or paper form, and may be shared among individuals for purposes of scholarly research or discussion, but may not be republished in any form, electronic or print, without prior, written permission from the author(s), and advance notification of the editors of MTO.

[2] Any redistributed form of items published in MTO must include the following information in a form appropriate to the medium in which the items are to appear:

This item appeared in Music Theory Online in [VOLUME #, ISSUE #] on [DAY/MONTH/YEAR]. It was authored by [FULL NAME, EMAIL ADDRESS], with whose written permission it is reprinted here.

[3] Libraries may archive issues of MTO in electronic or paper form for public access so long as each issue is stored in its entirety, and no access fee is charged. Exceptions to these requirements must be approved in writing by the editors of MTO, who will act in accordance with the decisions of the Society for Music Theory.

This document and all portions thereof are protected by U.S. and international copyright laws. Material contained herein may be copied and/or distributed for research purposes only.

Prepared by Sam Reenan, Editorial Assistant

Number of visits:

18151