Review of Timothy Johnson, John Adams’s “Nixon in China”: Musical Analysis, Historical and Political Perspectives (Ashgate, 2011)

Kyle Fyr

KEYWORDS: John Adams, music analysis, rhythm, transformational theory, metric dissonance

Copyright © 2012 Society for Music Theory

[1] In spite of John Adams’s popularity and the frequency with which his compositions are performed, there remain only a handful of full-length books devoted to his music. Adams also notes that the musical language of his opera Nixon in China is “difficult to summarize” (Adams 2008, 144). For these reasons, Timothy Johnson’s new book John Adams’s “Nixon in China” is a noteworthy endeavor, one that provides a thorough treatment of not only analytical but also historical and cultural contexts surrounding this extraordinary work.

[2] One of the most useful features of the book is its layout and organization. Instead of proceeding through the opera strictly chronologically, Johnson divides the book into three topical parts. Part I (Chapters 1–4) deals with the environments in which the opera takes place, Part II (Chapters 5–10) devotes a chapter to each of the opera’s six main characters, while Part III (Chapters 11–15) discusses the political and cultural issues that the opera raises. Chapter 15 is a particularly successful discussion of the ways in which the seemingly disparate perspectives of Richard Nixon and Mao Tse-tung (and by extension, America and China, or even more broadly, West and East) actually share some common ground. Chapters 5–10 are similarly useful, in keeping with Adams’s (and librettist Alice Goodman’s) desire to make Nixon in China a “character opera.” Johnson’s discussion in Chapter 5 of how the opera portrays Richard Nixon as a rounded character (going beyond typical media stereotypes) is effective, especially given that Adams is always disappointed when productions of the opera fail to capture its necessary subtlety and instead make “stiff cartoons of its characters” (Adams 2008, 141). Another useful aspect of the book’s organization is that Johnson consistently lists corresponding excerpts on the Elektra/Nonesuch recording, so that readers may easily find aural references for the passages discussed.

[3] The layout is not without its occasional difficulties, however. For example, Johnson’s discussion of Pat Nixon’s guided tour of China in Chapter 4 skips over (with only a brief mention) her “This is Prophetic!” aria. Johnson does eventually give this aria a thorough treatment in Chapter 6 (the character chapter on Pat Nixon), but since the aria is certainly the high point of Mrs. Nixon’s tour (and is indeed one of the most poignant moments in the entire opera), its absence from the “grand tour” discussion is notable. Similarly, the extraordinary duets of Act III between Mr. and Mrs. Nixon and between Chairman and Madame Mao are scarcely mentioned in the character chapters (discussion of them is instead largely postponed until Chapter 15). Since these duets arguably reflect the most personal aspects of each character, their absence here makes the character chapters seem somewhat incomplete.(1) It should be noted, however, that Chou En-lai’s touching soliloquy, which ends the opera, does receive thorough treatment in Chapter 10.

[4] Johnson’s discussion of the political circumstances surrounding the drama of the opera is another consistent strength of this book. He cites many illuminating sources, such as the biography of Pat Nixon by her daughter Julie, multiple collections of Mao’s own writings, Richard Nixon’s own memoirs and notes, as well as perspectives from political advisors and journalists who covered the president’s visit to China. The opera’s creators undoubtedly also read some of these same sources.

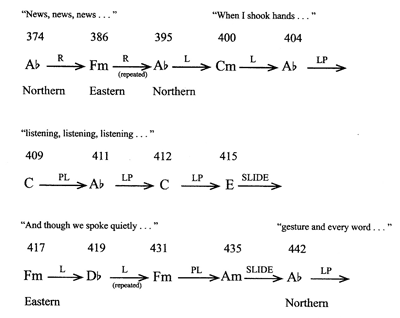

Example 1. Johnson’s Figure 5.1 (p. 93), which bears the caption “Harmonic content, transformations, and hexatonic systems: Nixon’s ‘News’ aria, first section (I/i/374–520).

(click to enlarge)

[5] To analyze pitch processes in Nixon in China, Johnson relies heavily on neo-Riemannian transformations P, L, R, and SLIDE, all of which find their contemporary origin in the work of David Lewin (1987). Given that Adams describes his score as “emphatically triadic in a way that no other work of mine ever dared to be” (2008, 144), and that the four aforementioned transformations are used with considerable frequency, Johnson’s approach seems quite sensible. In his analysis of Richard Nixon’s “News” aria (reproduced as my Example 1), Johnson effectively uses triadic transformations (especially SLIDE) to illustrate Nixon’s shifting moods. Each time a SLIDE transformation occurs, Johnson notes that it corresponds with a change in Nixon’s mood, from outward and optimistic to inward and pensive. Less effective is Johnson’s invocation of hexatonic systems here, as this obliges him to interpret the R transformations at the beginning of the aria—which are less persuasive as markers of mood changes than the subsequent SLIDE transformations—as additional mood shifts. Nonetheless, this is one of the more compelling analyses in the book, fusing as it does convincing technical analysis with hermeneutic insight.

[6] Not all of Johnson’s analyses are so successful, in part because of his heavy reliance on triadic transformations. For instance, he is sometimes forced to marginalize the presence of sevenths in one or both chords in order to label a succession as P, L, R, or SLIDE (with a caption such as “add seventh” below the transformational arrow). At other times (as in his analysis of the opening “Soldiers of Heaven” chorus), Johnson overlooks “transient” chords in order to invoke neo-Riemannian connections among “more significant” harmonies (216). Since one of the main purposes of neo-Riemannian transformations is to show parsimonious voice-leading connections between chords, such analysis is less illustrative when the chords in question are not adjacent.(2)

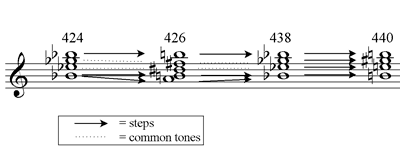

Example 2a. Johnson’s Figure 6.1 (p. 106), which bears the caption “Harmonic content and transformations, and hexatonic systems: Pat’s aria, ‘This is Prophetic!’ (II/i/424–598).”

(click to enlarge)

Example 2b. Smooth voice-leading connections in Pat Nixon’s “This is Prophetic!” aria.

(click to enlarge)

[7] In Pat Nixon’s “This is Prophetic!” aria, Johnson finds that he cannot simply rely on neo-Riemannian transformations to explain chord progressions, instead summarizing the aria’s harmonic content in his Figure 6.1 (reproduced as my Example 2a).(3) Johnson astutely notices a smooth recurring voice-leading progression (which he boxes in his figure), but what the remainder of his figure does not clearly illustrate is how smooth the voice leading is throughout the aria. Johnson provides a brief illustration in his Example 6.7 (107), and if he had continued this type of diagram further, he could have much more clearly illustrated the aria’s extraordinarily smooth voice leading. (I have provided a hypothetical realization of such a diagram as my Example 2b.)

[8] One confusing aspect of Johnson’s analyses involves his definition of the dominant and subdominant (D and S) transformations, beginning in Chapter 9.(4) Johnson defines the D transformation as “a contextual inversion around the fifth of a major triad or the root of a minor triad” while the S transformation describes the opposite (137). In other words, Johnson’s D transformation would map an F-major triad onto a C-minor triad (and back again with an additional iteration of D), while his S transformation would map an F-minor triad onto C-major triad (and back with an additional S). These definitions are confusing for several reasons. First, Johnson’s definitions are not standard interpretations of D and S transformations. Lewin defined the dominant transformation so that it maps every triad to a triad of the same mode a perfect fifth lower and defined the subdominant transformation so that it maps every triad to a triad of the same mode a perfect fifth higher (Lewin 1987, 176–77). Mode changes are thus not a part of Lewin’s D and S transformations, nor are these operations —unlike P, L, R, and SLIDE—their own inverses. Secondly, other authors have already defined the transformations described by Johnson’s definitions under other names. For example, Johnson’s D would be 〈–, 7, 5〉 under Julian Hook’s Uniform Triadic Transformations (UTT) (Hook 2002) and has been called R′ by Robert Morris (Morris 1998). Johnson’s S would then be UTT 〈–, 5, 7〉 according to Hook and L′ according to Morris; Richard Cohn and David Kopp have also discussed this transformation, labeling it N (for

Nebenverwandt) and F (for fifth-change), respectively (Cohn 1998; Kopp 2002). Thirdly, Johnson invokes compound transformations (such as PR and PLP) at many other times throughout the book. Why not then simply label what he calls D as LRP (or PRL) and label what he calls S as PLR (or RLP)? Finally, Johnson seems to have occasionally confused even himself with these definitions. In his Figure 9.1 (136–37), for example, he labels a transformation from

Example 3a. Pulse-stream analysis of Act III, measures 704–5.

(click to enlarge)

Example 3b. Pulse-stream analysis of Act III, measures 840–45.

(click to enlarge)

Example 3c. Pulse-stream analysis of Act III, measures 812–14.

(click to enlarge)

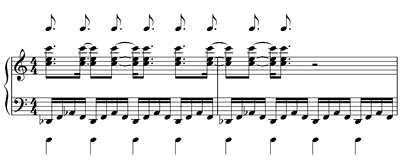

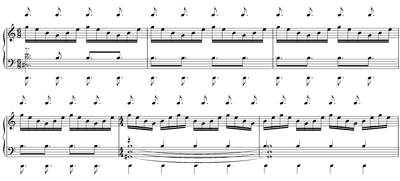

[9] Johnson employs Harald Krebs’s theories of metric dissonance (Krebs 1999) to describe rhythmic phenomena in Nixon in China. This approach provides him with shorthand labels that often substitute for visual musical examples.(5) Johnson’s metric dissonance analyses are more consistently persuasive than his harmonic analyses in that his approach is clearly laid out in the introduction and remains consistent throughout the book. Here I would also propose a complementary approach, however, as metric dissonance analysis tends to privilege the notated time signature as a primary metric consonance and lacks the flexibility to capture all aspects of Adams’s rhythmic style. Sometimes Adams’s writing closely aligns with the notated time signature, but at other times this is not true. Further, it is rarely clear in Adams’s music that one pulse layer should be privileged over another.(6) Adams notes that his “other life” as a conductor has convinced him to “take the route of least resistance in terms of notation unless something simply makes no sense theoretically” (1996, 94). Because the various pulse streams that emerge from the musical surface do not necessarily always correspond with notated time signatures in Adams’s music, I have argued elsewhere (Fyr 2011) that John Roeder’s pulse stream analysis provides a more useful method for analyzing these phenomena—his approach tracks distinct pulse continuities, rather than hierarchical levels or groupings (Roeder 1994). I have illustrated some of the benefits of pulse stream analysis with three short passages from Act III. The passage in Example 3a conveys similar information to a metric dissonance analysis, but without undue focus on the notated time signature. Example 3b then illustrates a passage where pulse streams shift from an aligned to an unaligned state even though one stream remains constant. Finally, Example 3c illustrates pulse streams (none of which confirm the notated time signature) that are both changing and unaligned with each other. Pulse stream analysis thus flexibly conveys a wide variety of rhythmic information without hierarchical implications. It necessitates more visual musical examples and eliminates the convenience provided by shorthand metric dissonance labels, but it helps to capture Adams’s unique rhythmic style to a greater degree.

[10] The book is, on the whole, attractively laid out and cleanly edited. Spelling errors are mostly innocuous, but a few do actually confuse the meaning of a paragraph or sentence.(7) Johnson generously cites previous research, but Adams’s 2008 autobiography is conspicuously absent from Johnson’s references. Perhaps Johnson completed much of his research for this book prior to 2008 or found similar information in other sources, but given that Adams devotes twelve pages of his autobiography to discussing the background, creation, and musical aspects of Nixon in China, its absence from Johnson’s list of works cited is noteworthy.

[11] In summary, Johnson’s book provides a thorough and cleverly organized account of Adams’s Nixon in China. While certain problems with the analyses may limit the book’s appeal for theorists, it will nevertheless appeal to a wide range of readers. Even those who are already very familiar with the opera will likely find their knowledge of its historical and political contexts greatly expanded by Johnson’s writing.

Kyle Fyr

University of Northern Colorado

School of Music

Frasier Hall 122

Campus Box 28

Greeley, CO 80639

kyle.fyr@unco.edu

Works Cited

Adams, John. 2008. Hallelujah Junction: Composing an American Life. New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux.

Cohn, Richard. 1998. “Square Dances with Cubes.” Journal of Music Theory 42: 283–96.

Fyr, Kyle. 2011. “Proportion, Temporality, and Performance Issues in Piano Works of John Adams.” PhD diss., Indiana University.

Hook, Julian. 2002. “Uniform Triadic Transformations.” Journal of Music Theory 46, 1/2: 57–126.

Jemian, Rebecca and Anne Marie de Zeeuw. 1996. “An Interview With John Adams.” Perspectives of New Music 34: 88–104.

Kopp, David. 2002. Chromatic Transformations in Nineteenth-Century Music. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Krebs, Harald. 1999. Fantasy Pieces: Metrical Dissonance in the Music of Robert Schumann. New York: Oxford University Press.

Lewin, David. 1987. Generalized Musical Intervals and Transformations. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Morris, Robert. 1998. “Voice-Leading Spaces.” Music Theory Spectrum 20: 175–208.

Roeder, John. 1994. “Interacting Pulse Streams in Schoenberg’s Atonal Polyphony.” Music Theory Spectrum 16: 231–249.

Footnotes

1. Fans of the opera may actually find the exquisite Act III to be generally underrepresented in this book.

Return to text

2. A few of Johnson‘s chord labels in the “Soldiers of Heaven” analysis (for example, in his Figure 14.1) are also questionable because they ignore important bass notes. Further, measure 144 is mislabeled as

Return to text

3. Note that the B7 chord at “mortality” should be labeled measure 492, not measure 592. I occasionally disagree with Johnson‘s chord labels here as well, but the frequently oscillating texture causes enough ambiguity that multiple interpretations are sometimes possible.

Return to text

4. I would like to thank Julian Hook for his invaluable comments and suggestions regarding the issues discussed in this paragraph.

Return to text

5. Though Johnson always refers to bars in the score, his analyses of metric dissonance would be greatly enhanced by supplying more musical examples. The reproduction of such excerpts is admittedly cost prohibitive, but the benefit to readers would be substantial.

Return to text

6. Pat Nixon‘s “This is Prophetic!” aria is a prime example in this regard. It features constant dotted-quarter-note pulses in the upper register and constant quarter-note pulses in the lower register, while the vocal line sometimes aligns with one pulse stream and sometimes aligns with the other.

Return to text

7. For example, page 38 contains references to a diatonic and harmonic “pallet” where the correct word would be palette, page 229 references a “topical” storm where the word should be tropical, and the final sentence of the book notes the characters finding comfort in their most “venerable” moments (here I assume Johnson meant vulnerable moments).

Return to text

Copyright Statement

Copyright © 2012 by the Society for Music Theory. All rights reserved.

[1] Copyrights for individual items published in Music Theory Online (MTO) are held by their authors. Items appearing in MTO may be saved and stored in electronic or paper form, and may be shared among individuals for purposes of scholarly research or discussion, but may not be republished in any form, electronic or print, without prior, written permission from the author(s), and advance notification of the editors of MTO.

[2] Any redistributed form of items published in MTO must include the following information in a form appropriate to the medium in which the items are to appear:

This item appeared in Music Theory Online in [VOLUME #, ISSUE #] on [DAY/MONTH/YEAR]. It was authored by [FULL NAME, EMAIL ADDRESS], with whose written permission it is reprinted here.

[3] Libraries may archive issues of MTO in electronic or paper form for public access so long as each issue is stored in its entirety, and no access fee is charged. Exceptions to these requirements must be approved in writing by the editors of MTO, who will act in accordance with the decisions of the Society for Music Theory.

This document and all portions thereof are protected by U.S. and international copyright laws. Material contained herein may be copied and/or distributed for research purposes only.

Prepared by Carmel Raz, Editorial Assistant

Number of visits: