Demographics, Analytics, and Trends: The Shifting Sands of an Online Engagement with Music Theory

Matthew Shaftel

KEYWORDS: MTO, history of theory, Society for Music Theory, demographics.

Copyright © 2014 Society for Music Theory

[1] Many greetings to you all, gentle readers of MTO! This year we celebrate the full fruition of an idea that nobody could have imagined just 22 years ago. The storied cast of characters collected in this special collection has described MTO’s humble beginnings as well as its innovative use of technology and design. By the time I joined up as editor with Tim Koozin in 2008, MTO was already at the cutting edge. All Brent Yorgason, Sean Atkinson, and I had to do was spruce up the look and update a few features. Instead, I concentrated my time as editor on growing our pool of authors and establishing a broader readership, which was made significantly easier by the addition of Google Analytics in 2006. The ability to track readership in real time and to reach an ever increasing diverse group of authors at the drop of a hat allowed (and continues to allow) MTO to stay ahead of the curve, not just technologically, but also in its reaction to scholarly trends. In particular, an expansion of MTO’s tradition of special volumes devoted to particular topics gave us an opportunity to reach out to new authors. Even better, these special volumes captured a rapidly growing readership. Indeed, six of our eight most read volumes over the past two decades are special volumes, and nine of the twenty-five most read volumes are special volumes, accounting for more than 50% of the readership for this group.(1) My task in the present special collection is to relate MTO’s history to our discipline, employing data from web analytics as well as from submission and publication reports in order to explore trends in topics and demographics across the journal’s 20 years of publications. Ultimately, this will provide a unique record of the Society for Music Theory’s most public voice while pointing to developing trends. So, let’s start with a simple question.

I. Who Reads MTO?

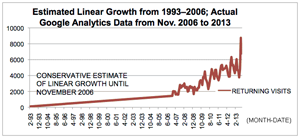

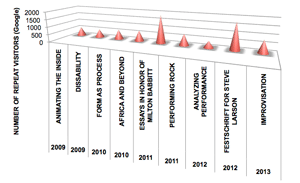

Figure 1. Number of returning visits to MTO

(click to enlarge)

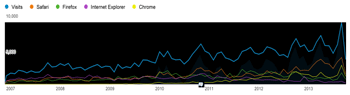

Figure 2. Actual Google Analytics data from November 2006 to November 2013, including browser information

(click to enlarge)

Figure 3. Google Analytics data showing repeat visits disaggregated by country (November 2006 to November 2013)

(click to enlarge)

Figure 4. Number of repeat visitors from countries in Western Europe (Google Analytics)

(click to enlarge)

[2] The answer is that many, many people read MTO. Using Google Analytics to track readership since 2006 (the first year that we implemented this tool), and conservatively estimating based on linear growth starting in 2003, MTO has had 1,504,811 unique visitors and approximately 418,897 return visitors. In the last seven years alone there have been over 46,000 visits to MTO lasting more than ten minutes, with many of them lasting significantly longer.

[3] Figure 1 shows the tremendous growth of returning readership to MTO. The conservative estimate of linear growth is shown by the straight line to November 2006. The wiggly graph that follows is actual data from Google Analytics.

[4] Figure 2 shows just the seven years of Google Analytic data, counting repeat visits, rather than unique visits.(2) The peaks in the blue repeat-visitor line generally coincide with the regular release of new volumes, which always bring a burst of interest in the journal. The very steep peak on September 16, 2013, for instance, coincides exactly with the announcement of MTO volume 19.3. Note, too, that the MTO audience has become increasingly Macintosh oriented, and, between January 2011 and October 2013, there have been over 9,000 return visitors using mobile devices, most of them on a gadget made by Apple.(3) Mobile users still represent only about 17% of MTO’s readership. This number is continuing to grow, however.

[5] Figure 3 includes a graphic from Google Analytics that shows repeat visits disaggregated by country. Not surprisingly, the vast majority of our readers hail from the U.S. and Canada. However, we also have a number of readers from overseas. The English-speaking world is well represented, with the U.K., New Zealand, and Australia among our most frequent international readers, but Spain and Belgium have a larger number of readers. This is supported by Google translator data, which shows over 19,000 repeat visitors who translated MTO pages into Spanish. Significant numbers of return visitors (that is, more than 2,000) have also translated MTO’s pages into French, Dutch, German, and Brazilian Portuguese.(4) I’ll now take a closer look at the statistics from Europe (see Figure 4).

[6] The number of repeat visits from readers in mainland Europe was steady for many years, but picked up dramatically in mid-2011, driven largely by a temporary increase in traffic from Belgium, which was then picked up by traffic from Germany and the Netherlands. Overall, though, a growing Internet presence and the improvement in web translators has increased MTO’s overseas readership, which accounts for 37% of our repeat readers.

II. How many articles and essays are published in MTO?

[7] I will now turn away from overall readership numbers and look at submission rates, author diversity, and topic trends in MTO’s history. This data is drawn from the volumes of MTO itself, from publication reports (which are only extant starting in 2002), and additional Google Analytics filters.(5)

Figure 5. MTO submission and acceptance data

(click to enlarge)

[8] Figure 5 shows the number of articles and essays submitted to and accepted by MTO over the 20-year history,(6) and the number of these that were authored by women. Due to the fact that publications-committee reports are not available prior to 2002, submission data only represents 2002–2013. Some points of interest to note:

- The overall number of submissions has grown substantially since 2002. Indeed, MTO has consistently received between five and six times more submissions than it received in 2002.

- The total number of accepted items has also grown fairly steadily since around 1999. The first several years of the journal saw a higher degree of activity, with approximately twenty items published per year. A return to that degree of activity occurred around 2007 and has settled around thirty to forty items per year since 2009.

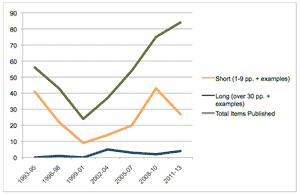

Figure 6. Unusually brief or extended articles published in MTO (1993–2013)

(click to enlarge)

[9] The gender diversity of our authorship is on the right track, as shown by the generally increasing number of submissions by women authors (up from four in 2002 to twenty-three for each of the past two years), but still leaves a good deal of room for improvement. With roughly 30% of our society membership made up of scholars who are women, it is noteworthy that it was only in 2002, 2005, 2012, and 2013 that nearly (but not quite) 30% of the incoming submissions were by women. In the years 2003, 2004, 2005, 2008, and 2010, 30% or more of the accepted items were by women. The year 2009 saw twelve published items that were authored by women, but that number has not been sustained in the four years that have followed.

[10] Music-theoretical publications tend to be rather significant in length, with some articles extending well over thirty pages of text.(7) These unusually long articles have generally been impractical to publish in the more traditional print journals in our field. In addition, some scholars have lamented a lack of venues for more brief forays into musical considerations. For the past two decades, MTO has been providing a consistent venue for music-theory research of all lengths, and, while the percentage of published items that are brief has dropped from 72% in its first three years to 32% in 2011–2013, the number of brief essays and commentaries published each year is still significant (see Figure 6).

III. What areas of research are found in MTO?

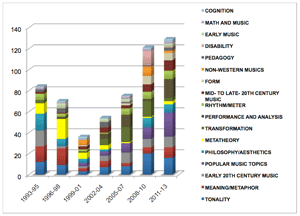

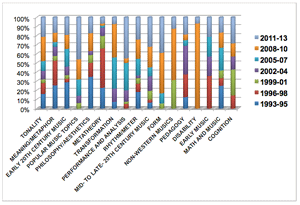

Figure 7. Topics of published MTO items (1993–2013)

(click to enlarge)

[11] Figure 7 shows the topics of published MTO items over the 20-year history (grouped into three-year time spans). Note that an item may fit into more than one topic, so roughly 50% of items are double counted in this chart. The topics are listed in order from most to least common (as represented by the total number over the MTO lifespan). For instance, over the past two decades there have been 75 items on tonal subjects, 59 items that engage musical meaning or metaphor, 52 that discuss music from the early-twentieth century, and 50 that focus on popular music topics. Some points of interest regarding Figure 7:

-

The number of topics engaged in each three-year time span has grown steadily over time, with only ten topics in 1993–1995, to thirteen in 1999–2001, to sixteen in 2008–2010, to seventeen in 2011–2013. This may be accounted for in part by the increased number of published items in each period, as shown in Figure 6.

-

With the one exception of 1996–1998, a relatively even distribution of major topics has continued to be manifest in MTO. The top five topics in MTO’s first years were each represented by between ten and sixteen items. In the most recent three-year periods, the six most popular topics have each been represented by at least nine items. The outliers here are popular-music and tonal-music topics, which, while being significantly more represented than other topics, have still only accounted for 28% of items over the past six years.

- The change in the number of topics represented in any three-year period cannot be linked directly to the addition of particular topics over time. For instance, there were no early-music items published in the periods starting in 1993, 1999, and 2008, but every other time span included at least three. On the other hand, work on issues of disability was introduced in the special volume in 2009, with one additional item published in 2013.

Figure 8. Distribution of topics over time

(click to enlarge)

[12] Figure 8 shows the relative distribution of individual topics over time, normalized as a percentage of total items published within a particular topic. The different colors represent three-year spans, from the earliest (in dark blue on the bottom), to the most recent (in light blue on the top). Topics are listed from most common on the left to least represented on the right, so one might note that, although cognition is the least represented (with only seven items over twenty years), those articles have been relatively evenly distributed since the first cognition article in 1998. As I stated previously, many topics have maintained a fairly steady presence over MTO’s lifespan:

-

The three most common topics (tonality, meaning/metaphor, and early twentieth-century music), have been relatively steadily represented over MTO’s lifespan.

-

MTO’s long commitment to publishing SMT keynotes and plenary sessions results in a relatively even presence of metatheoretical topics over the past twenty years, although, as the overall number of items published each year has grown, this has become a smaller percentage of the total.(8)

- Other topics that have been relatively evenly represented throughout MTO’s lifespan include philosophy and aesthetics, with greater representation both early and more recently; math/music and pedagogy, with fairly low numbers overall; and rhythm and meter, with a modest degree of recent growth, mostly driven by an overlap in the number of popular music and non-western publications that also engage rhythm and meter (twelve items).

[13] Figure 8 also shows a number of growth areas in scholarly research:

-

Publications on non-western music are largely aggregated in two special volumes devoted to the topic in 2000 (Volume 6.1) and 2010 (Volume 16.4). As mentioned previously, research on disability is largely focused in a single combined special volume:

15.3 and

15.4. While neither of these areas has shown linear growth, they clearly represent areas of growth.

-

Popular music topics, however, have seen tremendous and steady growth, from a single publication in 2001 (Mark Butler’s stunning article on electronic dance music), to twenty-three items in the past three years.

-

Other growth areas include performance and analysis, a recurrent topic throughout MTO history, and one that has seen several special volumes; and form, likely sparked by the publication of Bill Caplin’s (1998) book on classical form, Hepokoski and Darcy’s (2006) book on sonata theory, and the Tempest Sonata special MTO volume in 2010 (Volume 16.2). The publication of research that focuses on more recent composition has also seen consistent growth over MTO’s lifespan.

- The topic of transformational theory saw tremendous growth between the first year of MTO and a flurry of publications in 2008, but has seen significantly less activity in the past five years.

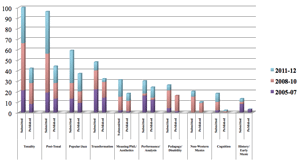

Figure 9. Topics of items submitted vs. items published (2005–2012)

(click to enlarge)

[14] Figure 9 shows the topics and number of items submitted compared with the topics and number of items published. Data for items submitted is drawn from publications reports, which cover a slightly variable ten-to-twelve-month period, since the reports are submitted sometime between August and October. The data for items published is taken from actual volume years, so there is some discrepancy in terms of dates, but it still provides a general picture of submissions vs. acceptance. Note, too, that this chart does not distinguish between solicited items for MTO’s many special issues (which are still subject to review and potential rejection, but tend towards a higher acceptance rate) and the items that are submitted and accepted through the traditional peer-review process (for which the average acceptance rate ranges between 20 and 30%). Thus, the small number of submissions and the significantly lower acceptance rates for research in cognition (13% acceptance) and early music (23% acceptance) may well be related to the lack of special volumes in those areas. By contrast, the higher acceptance rate in several areas is directly related to articles in special volumes or collections of commentaries based on a particular article (as in the case of transformation, whose acceptance rate and submission numbers were boosted in 2007 and 2008 by responses to Michael Buchler’s “Reconsidering Klumpenhouwer Networks,” published in Volume 13.3). Finally, given the slightly higher acceptance rates and the higher number of items published overall, one might conclude that submissions that focus on post-tonal topics, popular music, jazz, or performance and analysis are more likely to be published. On the other hand, if everyone flocks to a single corner of our discipline (as turkeys do in a thunderstorm), these areas of scholarship are likely to become saturated.

Figure 10. Music Theory Spectrum: topics of items submitted vs. items published

(click to enlarge)

[15] Just by point of comparison, Figure 10 shows the topics of items submitted vs. items published for the past six years in Music Theory Spectrum (data drawn from publications reports). The profile is quite different, with a smaller range of topics, and a more significant representation of more traditional post-tonal and tonal topics. This emphasis may be a product of the large number of submissions MTS receives in these areas. Contrast MTS’s 38 popular-music/jazz submissions received compared to approximately 50 received by MTO over the same time period. Much more significantly, however, whereas popular-music topics have a particularly high acceptance rate at MTO, they have a relatively low acceptance rate at MTS. Post-tonal topics, however, have a comparable acceptance rate at both MTS and MTO. Cognition work is also much more likely to be submitted to and published by MTS. The net result is that the two journals have very distinct “flavors,” and I believe that our society finds value in this difference.

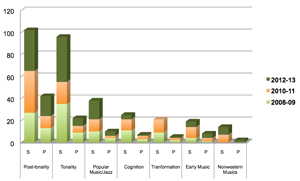

IV. Which areas of research do MTO readers prefer?

Figure 11. Most popular topics by number of repeat readers

(click to enlarge)

[16] Figure 11 draws from Google-Analytic data for the 100 most read articles over the past six years, taking the number of repeat readers for each article and aggregating by topic. The number next to the topic name is the number of items published in the relevant area of research. The figure provides a rather incomplete picture, of course, since it does not measure anything published before 2006, and items published more recently have had significantly less time to accumulate readership. As such, high readership for articles published between 2010 and 2013 is particularly noteworthy. While the readership may partly reflect the number of available articles in a particular topic, this is not always the case. One obvious exception is the tremendous readership of popular music topics, which outpaces the readership of tonal topics by nearly 3,000 readers. The extra readership is drawn entirely from publications within the past three years, which may reflect a preference for very recent scholarship in this area. If that is the case, we should expect to see a drop-off in the popularity of these particular articles, to be replaced in popularity by more recent scholarship on popular musics.

Figure 12. Most read special volumes (These account for more than 50% of the readership of the top 25 volumes)

(click to enlarge)

[17] Other areas seem to have a healthy degree of longevity, if not overall popularity. In particular, the older items that explore tonal, early twentieth century, and early-music topics continue to have a strong readership. Despite the smaller number of published items, rhythm and meter and early-twentieth-century music topics have attracted more readership than transformational theory. This may reflect the recently declining number of submissions and publications in that area. Finally, as summarized in Figure 12, special volumes attract an unusually wide readership, while drawing from a diverse authorship. The eight special volumes in Figure 12 account for more than 50% of the readership of the top 25 MTO volumes of all time, and six of these are in the eight most read volumes.

V. What is the future of MTO?

[18] How might we best use this data to position MTO for the future? There are, of course, many possible answers to these questions, but here is a short list of ideas to begin the conversation:

-

It seems likely that readership will continue to grow, but perhaps we might invite a larger overseas readership by considering articles or a special volume in Spanish or German.

-

Given MTO readership’s preference for articles on highly contemporary popular and art music, it may be important for the journal to stay as current as possible in these areas.

-

It would be wise to continue to balance the focus on cutting-edge music with research in the more traditional scholarly areas, which has a greater longevity among MTO’s readers. Perhaps MTO should continue encouraging innovative formats in these traditional areas, following models like the one set by Joe Straus’s “Three Stravinsky Analyses” (Volume 18.4).

-

MTO should continue to attract articles of every possible length, particularly those outliers at the longer and briefer ends of the spectrum.

-

Authorship and readership has grown, and MTO should continue to be the journal that opens the door to a wide variety of authors and many new readers through special volumes and careful mentorship of articles that have a great deal of potential.

- Diversity of authorship is critical to every aspect of our discipline, so MTO (and SMT in general) needs to make sure that its practices reflect this importance.

[19] Most of all, MTO must continue to innovate, experiment, and take chances! As SMT’s most public voice, MTO acts as a barometer of the discipline, reacting nimbly to the challenges, opportunities, and many-faceted areas of inquiry that characterize music theory. Here’s to another twenty years on the cutting edge!

Matthew Shaftel

Florida State University

College of Music

Tallahassee, FL 32306-1180

mshaftel@fsu.edu

Works Cited

Caplin, William E. 1998. Classical Form: A Theory of Formal Functions for the Instrumental Music of Haydn, Mozart and Beethoven. New York: Oxford University Press.

Hepokoski, James, and Warren Darcy. 2006. Elements of Sonata Theory: Norms, Types, and Deformations in the Late Eighteenth-Century Sonata. Oxford University Press.

Footnotes

1. The eight most read volumes are:

13.3,

16.2,

16.4,

17.2,

17.3,

18.3,

19.2,

19.3.

Return to text

2. The number of unique visitors is a significantly higher number, but includes a large percentage of visitors (as much as 60%) that immediately click out of MTO. I have thus chosen to represent quality visits as repeat visitors.

Return to text

3. Drawn from Google Analytics data as of October 31, 2013, but not shown here.

Return to text

4. Google Analytics data from October 31, 2013.

Return to text

5. I would like to thank Kaleb Delk for helping me to collect and process this data.

Return to text

6. Note that the publication report for 2008 was submitted six weeks earlier than is typical and thus the numbers are lower than those for the surrounding years.

Return to text

7. Based on printing MTO article pages as a PDF.

Return to text

8. Cristle Collins Judd in 19.3, Patrick McCreless in 17.1, Susan McClary in 16.1, Janet Schmalfeldt in 10.1, Twenty-Fifth Anniversary Banquet Lectures in 9.1, 1999 Plenary Session in 6.1, 1998 Plenary Session in 4.2, Kofi Agawu in 2.4.

Return to text

Copyright Statement

Copyright © 2014 by the Society for Music Theory. All rights reserved.

[1] Copyrights for individual items published in Music Theory Online (MTO) are held by their authors. Items appearing in MTO may be saved and stored in electronic or paper form, and may be shared among individuals for purposes of scholarly research or discussion, but may not be republished in any form, electronic or print, without prior, written permission from the author(s), and advance notification of the editors of MTO.

[2] Any redistributed form of items published in MTO must include the following information in a form appropriate to the medium in which the items are to appear:

This item appeared in Music Theory Online in [VOLUME #, ISSUE #] on [DAY/MONTH/YEAR]. It was authored by [FULL NAME, EMAIL ADDRESS], with whose written permission it is reprinted here.

[3] Libraries may archive issues of MTO in electronic or paper form for public access so long as each issue is stored in its entirety, and no access fee is charged. Exceptions to these requirements must be approved in writing by the editors of MTO, who will act in accordance with the decisions of the Society for Music Theory.

This document and all portions thereof are protected by U.S. and international copyright laws. Material contained herein may be copied and/or distributed for research purposes only.

Prepared by Carmel Raz, Editorial Assistant

Number of visits:

7438