Review of Laurel Parsons and Brenda Ravenscroft, eds., Analytical Essays on Music by Women Composers: Concert Music, 1960–2000 (Oxford University Press, 2016)

Laura Emmery

KEYWORDS: women composers, octatonicism, serialism, gesture, feminist theory, music identity, Mamlok, Beecroft, Tower, Gubaidulina, Chen Yi, Saariaho, Larsen, Lutyens

Copyright © 2017 Society for Music Theory

[1] The publication of Analytical Essays on Music by Women Composers: Concert Music, 1960–2000 is timely. Both of its editors, Laurel Parsons and Brenda Ravenscroft, have chaired the Committee on the Status of Women, a standing committee of the Society for Music Theory. A principal motivation for their book is a sobering statistic collected by the committee: since 1995, only 1.51% of all articles published in peer-reviewed music theory journals have been devoted to music by women composers (3). With the publication of this much-needed collection of essays—the first of its kind—the editors seek to bring scholarly attention to outstanding female composers of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries and to ignite readers’ interests in this exciting contemporary concert music.

[2] The present collection is the third of four volumes in a set entitled Analytical Essays on Music by Women Composers; the other three volumes, all forthcoming, are focused on secular and sacred music to 1900, concert music from 1900 through 1960, and electroacoustic, multimedia, and experimental music from 1950 through 2015. Together, the essays cover a wide range of genres: small chamber works such as trios and string quartets; large-scale orchestral music such as concertos and symphonies; and compositions for voice, including songs, song cycles, and choral music.

[3] The detailed theoretical studies adopt a variety of analytical approaches, grouped thematically into three sections. In “Order, Freedom, and Design,” three essays illustrate the distinctive roles of serialism and octatonicism in post-war works of Ursula Mamlok (1923–2016), Norma Beecroft (b. 1934), and Joan Tower (b. 1938). The second section, “Gesture, Identity, and Culture,” includes essays that examine how the identities of Sofia Gubaidulina (b. 1931) and Chen Yi (b. 1953) reveal the significance of musical gesture in their compositions. Finally, “Music, Words, and Voices” concentrates on music with text, considering the notion of identity where music and words converge. This part features analyses of compositions by Kaija Saariaho (b. 1952), Libby Larsen (b. 1950), and Elisabeth Lutyens (1906–83).

[4] At the start of each section is a short introduction that explains the theoretical approaches uniting the essays within the section: pitch organization in Part I, gestural and cross-cultural theory in Part II, and text settings in Part III. Before each essay is a brief biographical sketch of the composer, providing readers with some cultural and professional context. Each analysis focuses on a single work (or a movement from a larger work), allowing readers to engage with a composer’s technique in detail by means of a representative case study.

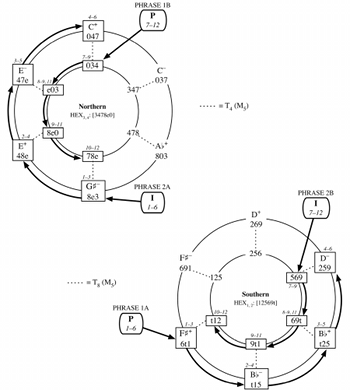

Example 1. Joseph Straus’s visualization of triads and (014)s plotted on Richard Cohn’s Northern and Southern hexatonic systems

(click to enlarge)

[5] Within Part I, chapter 2 opens with Joseph Straus’s analysis of the third movement of Mamlok’s Panta Rhei (Time in Flux), a twelve-tone piano trio from 1981. The analysis stems from Straus’s earlier essay on the same piece (2009, 140–45). His current study centers on Mamlok’s distinct form of serialism, the extension of the serial principle to rhythm, and dispelling the seven “myths” and mischaracterizations of post-war twelve-tone compositions in the literature (introduced in his 2009 essay). One compelling aspect of Straus’s analysis is his illustration of the interplay of consonant (037) and dissonant (014) collections throughout Mamlok’s work. Showing how (014) can be transformed into (037) and vice versa, Straus departs from Richard Cohn’s “Northern and Southern hexatonic systems” (1996, 2004) by introducing a new triadic circle inside the outer circle; Example 1 reproduces Straus’s visualization. The prose is complemented by diagrams and an annotated score, available in high resolution on the book’s companion website.(1)

[6] Christoph Neidhöfer’s outstanding study of Beecroft’s 1961 twelve-tone flute concerto, Improvvisazioni Concertanti No. 1, constitutes chapter 3. The title itself raises a question: how does integral serialism work within the framework of improvisation? Neidhöfer explains this paradoxical approach to composition through the writings of Umberto Eco, particularly Eco’s aesthetic on the dialogue of time. Further, Neidhöfer contextualizes Beecroft’s aesthetic historically: Beecroft worked on Improvvisazioni while attending summer seminars and festivals at Darmstadt and Dartington and while studying composition with Goffredo Petrassi, all during her three years in Europe (1959–61). Thus, it is not so unusual that she explored contemporary trends of total serialization, as well as the concepts of chance music and improvisation, during this period. Neidhöfer has once again (as in 2007, 2009, and 2012) expertly constructed a compelling narrative of a composer’s complex serial techniques informed by study of sketches and other original documents. For instance, drawing on original material from the University of Calgary Archives & Special Collections, the Archivio Luigi Nono in Venice, and the Paul Sacher Stiftung in Basel, Neidhöfer illustrates that Beecroft’s method—increasing tension through the interval successions of a row’s pitch pairs—also appears in the sketches of Maderna, who used the same interval classifications in his own music and while teaching composition to his students, including Luigi Nono. Loosely based on Paul Hindemith’s categorization of intervals, Maderna’s method (and hence Beecroft’s) assigns numeric values to intervals, classifying them from most consonant (+3 for perfect consonances) to least consonant (-2 for minor second and major seventh).

[7] In chapter 4, Jonathan Bernard examines Tower’s methods of employing octatonic collections in her 1986 orchestral composition, Silver Ladders. Scrutinizing the ways in which Tower gradually transforms one octatonic collection into another, or creates transitions from octatonic to non-octatonic collections, Bernard classifies six categories of techniques. Interestingly, he notes that some of these compositional strategies—namely, working with multiple transpositions and rotations of the octatonic collection at a time—are absent in the works of earlier twentieth-century composers. Thus, Bernard’s study is a significant contribution not only to the scholarship on Tower, but even more generally to our understanding of post-war American music.

[8] Chapter 5, the first essay of Part II, presents Judy Lochhead’s reading of female authorial identity in Gubaidulina’s String Quartet No. 2, composed in 1987. Lochhead also examines Gubaidulina’s techniques of repetition and contrast—integral processes in this quartet—in light of the Deleuzian philosophy of difference. By analyzing Gubaidulina’s use of timbre, articulation, pitch, dynamics, and register to shape small- and large-scale musical gestures, Lochhead distinguishes three categories of gestures, each characterized by several musical events: “reaching out and tethering” gestures in Part 1 of the quartet; “reaching up and renewing” gestures in Part 2; and gestures of “affirmation” in Part 3. Each event occurs in such a way as to maximize the concept of difference. Lochhead’s reading of Gubaidulina offers an insight into how the composer thinks, musically, of this concept: as the intertwining of sonic difference and repetition through the passage of time (105), which resonates with Deleuze’s notion of interlinking difference and repetition.

[9] In chapter 6, Nancy Yunhwa Rao analyzes Chen Yi’s compositional techniques in Symphony No. 2 (1993) from the perspective of gesture and personal identity. In particular, Rao is interested in Yi’s transfer of specific Chinese signifiers, such as rhythmic percussion gestures used in Chinese operas, to a Western symphony. The study builds on scholarship of musical gesture and embodiment (Cusick 1994, Mead 1999, Cumming 2000, Leong and Korevaar 2005, Hatten 2004, Lidov 1987, Lidov 2006, and Cox 2006).(2) However, as Rao notes, she departs from these earlier studies, which focus on music of the Western tradition, in that she extends the theories to Chinese culture. Rao’s essay is the only one in the collection that examines a work by a non-Western and transnational composer, and considers her use of polystylism in the global multiculturalism of the twenty-first century. Illuminating a variety of ways in which physical engagement relates to musical sound, musical gestures, and their expressive content, Rao offers even more than an interpretation of Chen Yi’s musical gestures within a transnational cultural context. Rao illustrates how musical gestures guide the symphony’s larger musical narrative and its dynamic process of spiritual transformation, hence interpreting the symphony from the perspective of shi, a concept in Chinese aesthetics (130).

[10] Chapter 7—now in Part III, on texted music—moves from polystylism to polyvocality. John Roeder analyzes Saariaho’s multivoiced representation of a single identity in “The Claw of the magnolia

[11] Brenda Ravenscroft’s own essay (chapter 8) considers two of Libby Larsen’s songs, “Bind me—I can still sing” and “In this short life,” both from her 1997 song cycle, Chanting to Paradise, for high voice and piano. Ravenscroft deftly interprets the relationship between poetry and music, analyzing Dickinson’s technical and expressive practices—such as her use of phonetic and syllabic patterns, and the structure of her poems. Ravenscroft also considers Larsen’s techniques of adapting and reconstructing Dickinson’s poems. By repeating and emphasizing specific words and sounds, Larsen derives musical form from poetic form. Thus, her music depicts more than a surface connection between songs and poetry (e.g., text painting); it fuses poetic and musical symbolism on a much deeper level (177–78). While Larsen has discussed her process of setting text to music, as well as the meaning of selected texts to her life experiences, Ravenscroft’s essay is the only theoretical analysis that examines music and poetry in Larsen’s vocal works.

[12] Finally, chapter 9 presents Laurel Parsons’s analysis of Elisabeth Lutyens’s 1968 composition for tenor, chorus, and orchestra, Essence of Our Happiness op. 69.(3) Unlike the pieces discussed in chapters 7 and 8, which exemplify the empowerment of female composers by setting the poetry of female poets, Lutyens’s composition sets a text by John Donne. However, Parsons argues that, despite its male-authored text and male soloist, the work portrays Lutyens’s own voice and identity unmistakably. For instance, in the second movement, Lutyens chooses a meditation by Donne that addresses the nature of time and human happiness. Parsons concludes that the composer echoes Donne’s text with her own perspective on the relationship between time and human happiness: Lutyens’s regrets, as a woman in her sixties, looking back on her own life (216–17). Parsons skillfully inserts Lutyen’s own voice into this study by incorporating the composer’s interviews and unpublished notes in relation to the selected introspective text. The end result is a candid glimpse into Lutyen’s personal struggles, both as composer and as a woman.

[13] As Parsons and Ravenscroft note, these essays do not attempt to create a new canon or paint a comprehensive picture of works by women composers (5). Rather, the aim of the collection is to present analyses of representative works by women composers of concert music in the latter part of the twentieth century—works that are at least as worthy of analysis and scholarly discourse as those of the more familiar twentieth-century canon. The collection achieves this goal, without question. My only qualm is that, by limiting its scope to concert music, the book is inherently less inclusive. It misses the opportunity to include composers such as Meredith Monk and Rachel Portman, who blend concert, film, and popular genres. Even within concert music, there are some curious omissions, such as the works of Jennifer Higdon or Unsuk Chin. Nonetheless, given the conscious effort by the music theory community to diversify the current musical canon, the impact of this book—especially as part of a four-volume series—will be to increase the visibility of women composers in classrooms, at conferences, and in published scholarship. These authors have taken the long overdue step of providing theoretical analyses on works by women composers. The rich diversity of analytical approaches make this volume suitable as a text for both general and topic-based courses on twentieth- and twenty-first-century music at the undergraduate and graduate levels.

[14] Analytical Essays on Music by Women Composers is a substantial addition to the scholarship of twentieth-century music. Encompassing a wide range of topics, the collection is of great importance to scholars with interests in pitch structure (serialism, octatonicism, set theory), gestural and cross-cultural theory, identity and feminist theory, and critical analysis of the relationship between text and music. The availability of the annotated examples, scores, and audio examples on the book’s companion website—materials that otherwise might be challenging to obtain—makes these works easily accessible for further study and discussion. More significantly, as the first book dedicated to the analyses of works by women composers, the volume sets a precedent for a more inclusive and diverse repertoire in the music theory literature, and will continue to serve as a significant marker in the expansion of the twentieth-century musical canon.

Laura Emmery

Emory University

1804 N Decatur Rd

Atlanta, GA, 30322

laura.emmery@emory.edu

Works Cited

Cohn, Richard. 1996. “Maximally Smooth Cycles, Hexatonic Systems, and the Analysis of Late-Romantic Triadic Progressions.” Music Analysis 15 (1): 9–40.

—————. 2004. “Uncanny Resemblances: Tonal Signification in the Freudian Age.” Journal of the American Musicological Society 57 (2): 285–324.

Cox, Arnie. 2006. “Hearing, Feeling, Grasping Gestures.” In Music and Gesture, ed. Anthony Gritten and Elaine King, 45–60. Ashgate.

Cumming, Naomi. 2000. The Sonic Self: Musical Subjectivity and Signification. Indiana University Press.

Cusick, Suzanne. 1994. “Feminist Theory, Music Theory, and the Mind/Body Problem.” Perspectives of New Music 32 (1): 8–27.

Everett, Yayoi Uno. 2012. “The Tropes of Desire and Jouissance in Kaija Saariaho's L’amour de loin.” In Music and Narrative since 1900, ed. Michael L. Klein and Nicholas Reyland, 329–45. Indiana University Press.

—————. 2015. Reconfiguring Myth and Narrative in Contemporary Opera: Osvaldo Golijov, Kaija Saariaho, John Adams, and Tan Dun. Indiana University Press.

Hatten, Robert. 2004. Interpreting Musical Gestures and Tropes. Indiana University Press.

Howell, Tim, Jon Hargreaves, and Michael Rofe, eds. 2011. Kaija Saariaho: Visions, Narratives, Dialogues. Ashgate.

Leong, Daphne, and David Korevaar. 2005. “The Performer’s Voice: Performance and Analysis in Ravel’s Concerto pour la main gauche.” Music Theory Online 11 (3).

Lidov, David. 1987. “Mind and Body in Music.” Semiotica 66 (1): 69–97.

—————. 2006. “Emotive Gesture in Music and its Contraries.” In Music and Gesture, ed. Anthony Gritten and Elaine King, 24–44. Ashgate.

Mead, Andrew. 1999. “Bodily Hearing: Physiological Metaphors and Musical Understanding.” Journal of Music Theory 43 (1): 1–19.

Moisala, Pirkko. 2000. “Gender Negotiation of the Composer Kaija Saariaho in Finland: The Woman Composer as Nomadic Subject.” In Music and Gender, ed. Pirkko Moisala and Beverley Diamond, 166–88. University of Illinois Press.

—————. 2010. Kaija Saariaho. University of Illinois Press.

Neidhöfer, Christoph. 2007. “Bruno Maderna’s Serial Arrays.” Music Theory Online 13 (1).

—————. 2009. “Inside Luciano Berio’s Serialism.” Music Analysis 28 (2–3): 301–48.

—————. 2012. “Berio at Work: Compositional Procedures in Circles, O King, Concerto for Two Pianos, Glossa, and Notturno.” In Luciano Berio: Nuove Prospettive / New Perspectives, ed. Angela Ida De Benedictis, 195–233. Leo S. Olschki.

Straus, Joseph. 2009. Twelve-Tone Music in America (Music in the Twentieth Century). Cambridge University Press.

Footnotes

1. The companion website contains the examples from all eight essays, including charts, diagrams, annotated scores, and in some cases audio recordings.

Return to text

2. Cusick and Mead explore the close connection between the body and the acts of performance, composing, and listening. Cumming, Leong, and Korevaar demonstrate the value of linking performers’ physical engagement with music to our understanding of musical voice and the analysis of musical gestures. Hatten, Lidov, and Cox address the embodiment aspect of musical gestures and how it can elicit the physical engagement of listeners.

Return to text

3. Given the difficulties of obtaining a recording for this piece, the online companion website offers a recording by the University of British Columbia Symphony Orchestra of an excerpt from Lutyens’s work.

Return to text

Copyright Statement

Copyright © 2017 by the Society for Music Theory. All rights reserved.

[1] Copyrights for individual items published in Music Theory Online (MTO) are held by their authors. Items appearing in MTO may be saved and stored in electronic or paper form, and may be shared among individuals for purposes of scholarly research or discussion, but may not be republished in any form, electronic or print, without prior, written permission from the author(s), and advance notification of the editors of MTO.

[2] Any redistributed form of items published in MTO must include the following information in a form appropriate to the medium in which the items are to appear:

This item appeared in Music Theory Online in [VOLUME #, ISSUE #] on [DAY/MONTH/YEAR]. It was authored by [FULL NAME, EMAIL ADDRESS], with whose written permission it is reprinted here.

[3] Libraries may archive issues of MTO in electronic or paper form for public access so long as each issue is stored in its entirety, and no access fee is charged. Exceptions to these requirements must be approved in writing by the editors of MTO, who will act in accordance with the decisions of the Society for Music Theory.

This document and all portions thereof are protected by U.S. and international copyright laws. Material contained herein may be copied and/or distributed for research purposes only.

Prepared by Tahirih Motazedian, Editorial Assistant

Number of visits:

5810