Review of Eric Wen, Structurally Sound: Seven Musical Masterworks Deconstructed (Dover Publications, 2017)

Michael Baker

KEYWORDS: Schenkerian analysis, musical interpretation, close reading

Copyright © 2018 Society for Music Theory

[1] Eric Wen’s Structurally Sound: Seven Musical Masterworks Deconstructed presents a collection of musical analyses from a Schenkerian perspective. Wen, a professor of music theory at the Curtis Institute of Music, and formerly on the faculty of the Mannes College of Music, has an impressive pedigree in the area of Schenkerian analysis, having studied privately with Carl Schachter before earning degrees at Columbia University and Yale University. The analyses in this book demonstrate a master teacher’s touch, and are well conceived and richly detailed. Wen’s preface gives no indication that he intends the book as a teaching manual; however, as I will discuss below, I believe it could serve effectively as a supplemental reading for introductory and intermediate studies in Schenkerian analysis. In all, the book reads as a compendium of not only Wen’s insights into the works in question, but also his views on the art of tonal music analysis. The book is abundantly illustrated with over 450 musical examples throughout its chapters, ranging from the very brief to the all-encompassing for each work in question.

[2] Following an introductory chapter, which reads like a brief explanation of Schenkerian concepts to the uninitiated, the book proceeds in seven chapters, each devoted to a work by Bach, Mendelssohn, Schubert, Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven, or Brahms.(1) Drawing on the main theme from the last movement of Beethoven’s “Pastoral” Symphony, the introduction presents a clear, well-argued summary of the essentials of Schenkerian analysis, and on its own would be a great, brief first reading for students and readers unfamiliar with this analytical approach. The choice of musical examples for the remainder of the book—focused on the pantheon of composers that Schenker so deeply venerated—is intentional. As Wen states: “The Austro-German Classical tradition from which these seven pieces stem represents a pinnacle of musical art. Even as we broaden our analytical range to embrace a multiplicity of popular and global musical styles, we should also strive to keep this great tradition alive” (xii).

[3] This statement, which prefaces the entire book and Wen’s broad project, is well-taken, as the analytical approach that he employs was created specifically to demonstrate consistency across the music of the Austro-German tradition. One might even go so far as to say that Schenker’s broader motive was to demonstrate the cultural superiority of the products of Austro-Germanic composers from Bach to Brahms, acknowledging all of the problematic value judgments that this entails for twenty-first-century musicians. However, I question whether this tradition needs to be defended among Schenkerians—and, if so, from whom? There is no shortage of new research devoted to these composers, and their music is central to the academic study of our art. Many of Wen’s chosen masterworks are among the most frequently performed compositions and will very likely remain so for the foreseeable future.

[4] Furthermore, whereas Schenkerian analytical principles have been and continue to be applied to a bewildering range of music—popular musical styles, jazz and improvisatory music, folk and world music traditions, neo-tonal music of Copland and Britten, and other music that Schenker never would have considered appropriate to his approach—the fact of the matter is that his canon remains central to the programs of Schenker-specific publications and conferences. For instance, a recently-published collection of Schenkerian essays is literally titled Bach to Brahms (Beach and Goldenberg 2015) and features analytical essays on the music of Schenker’s canon of composers. The choice of musical examples in recent textbooks on the subject (such as Cadwallader and Gagné 2010 or Damschroder 2017) reinforces this as well: they feature an overwhelming number of examples from the Austro-Germanic tradition, compared with a mere sprinkling of folk songs and music from slightly earlier periods. Moreover, there is a trend toward uniting aspects of Schenkerian theory with elements of other theories. Indeed, for each analytical approach to tonal music that has emerged during the past thirty to forty years—rhythm and meter studies, modern Formenlehre, neo-Riemannian studies, schema theory, and so forth—there is an essay synthesizing it with aspects of Schenkerian theory.

[5] Given that there is no need to promote the music of the Austro-Germanic tradition among Schenkerians, I believe that Wen’s motivation is instead to defend its place in the curriculum from those who would call for the radical re-forming of collegiate musical instruction, such as the authors of the much-discussed College Music Society Manifesto.(2) Among the recommendations from the CMS Task Force is for curricular inclusion of a wider range of musical literature—wider, at least, than that focused on European classical repertoire. In advocating for relevance and for preparing 21st-century musicians, the manifesto calls for supplementation—not replacement—of the European musical canon; however, the end result would necessarily be a drastic reduction in the amount of instructional time devoted to canonic composers during the four-year crucible of the typical undergraduate degree. Still others go further, advocating for a radical replacement of European classical music within the curriculum—that is, for firing a cannon at the canon.(3)

[6] Aside from these ambiguities over the purpose of the text, the analyses in the book are extremely clear and consistent in their application of Schenkerian principles. It is evident in the introductory chapter that Wen is a master teacher of Schenkerian analytical concepts, and the subsequent chapters demonstrate this as well. Wen mentions in the preface that what the book may be lacking in breadth, it will hopefully make up in depth (vii). This is certainly evident throughout the book, with many graphics and discussions of seemingly tiny details that have great impact on the individuality of the work in question. To borrow an image from Brian Alegant (2014), Wen’s approach seems more aligned with “scuba diving”—covering less content but exploring it in more detail—than with “snorkeling,” which emphasizes breadth of examples over depth of discussion.

[7] The notion of “scuba diving,” or close reading, gets at the heart of Wen’s approach to Schenker’s theory and his larger project in this book. In the epilogue, Wen mentions, in relation to understanding the background of a work: “[I]t’s not uncovering the background level that’s the most important objective, but seeing how the later levels of the middleground and foreground help to shape the individual profile of a specific composition. The events in the foreground are what distinguish a piece of music; the background provides a unifying force that establishes its coherence” (278). Wen’s words here echo Schenker’s explanation of structural levels (Schichten), which he maintained throughout his life. Schenker wrote, “when looking at the many possibilities of the Urlinie, one shouldn’t be concerned by the fact that they all resemble one another

Example 1. Example 1.79 of SS (page 50), illustrating motivic similarity between the opening and closing measures of Bach’s “Air” from the Orchestral Suite no. 3, BWV 1068 (mm. 1–2; mm. 15–18)

(click to enlarge)

Example 2. Example 3.28 of SS (page 90), showing a varied motivic recollection within Schubert’ “Nacht und Träume,” D. 827 (mm. 12–13; 15–17)

(click to enlarge)

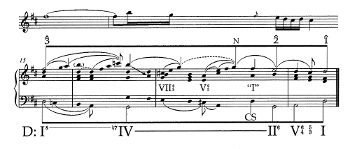

Example 3. Example 4.27 of SS (page 109), highlighting structural similarities between themes within the first movement of Haydn’s Symphony in G major, Hob. I: 94 (mm. 79–83; mm. 68–72)

(click to enlarge)

[8] One noteworthy aspect of Wen’s analytical approach is his careful attention to motivic processes. In chapter 1, on Bach’s “Air” from the Orchestral Suite no. 3, BWV 1068, Wen draws out a fascinating instance of motivic recollection of the opening motive within the closing measures (Example 1). In chapter 3, devoted to Schubert’s “Nacht und Träume,” Wen points out how the central G-major section includes a varied motivic repetition of a motive from earlier, and relates this to the distinction between dreams and reality within the song (Example 2). In chapter 4, on Haydn’s Symphony no. 94, he illustrates a motivic relationship between themes, despite their differences in surface details—a keen demonstration of Schenker’s famous motto, Semper idem, sed non eodem modo (Example 3). In chapter 5, on Mozart’s Symphony no. 40 in G minor, K. 550, Wen observes the – motion that opens the melody, compares it to treatments of the same scale-degree pattern in other works, and notes its long-held association with grief and even death. This is reminiscent of Carl Schachter’s (1999) discussion of the same issue in his classic article on motive and text in Schubert songs.(4) Wen’s attention to the motivic vitality of the works in question demonstrates a refined understanding of the issue, and serves as a good model for students to follow. A presentation strategy that Wen employs in these chapters, and one that recalls other master teachers whom I have observed and personally try to emulate in the classroom, is to introduce such fascinating motivic devices late in the discussion, as a kind of punctuation to the lesson (or article) at hand. In practice, I have found this strategy far more effective than clumsily blurting out the intricate motivic detail early on in the lesson; students are left far more convinced as to the explanatory power of Schenkerian analysis when such sumptuous desserts are offered at the end of the meal rather than at the beginning.

[9] Upon first reading, I was left wondering who the intended audience is for this book. Committed Schenkerians? If this is the case, Wen’s book reads like a collection of essays attempting to win battles that were already won long ago, akin to a fourth volume of Das Meisterwerk in der Musik written by someone who has taught the material for many years. There are no attempts to upend established modes of thought among theorists and musicians who are adherent to Schenkerian principles as they are taught in modern textbooks. And whereas Wen mentions that his readings of individual works may differ greatly from established analyses—his reading of Schubert’s “Nacht und Träume” contrasts nicely with Schachter’s (1999)—such competing analyses are commonplace in the music analytical tradition, especially among Schenkerians.

[10] Upon closer reflection, I find that the book reads more like a teaching manual—or, more precisely, as a set of supplemental readings for courses on Schenkerian analysis. The analyses are remarkably clear and go into tremendous depth in a variety of ways. The book could also be read as a variant of Deborah Stein’s 2005 edited volume, Engaging Music, focused solely on Schenkerian analysis and assigned to students to read as the semester unfolds. A distinct advantage of this book is that it is the product of a sole author; thus, Wen can control the consistency in application of (and attitude toward) Schenkerian analytical principles. I believe this pedagogical function is the greatest potential use of the text, and I could even envision framing an entire semester-long introduction to Schenkerian analysis as lessons on these works, using Wen’s text as the required reading for in-class discussions.(5) As it stands, the book is organized around a group of pieces, not around a set of topics, as many introductory courses on Schenkerian analysis are. There are, however, cogent descriptions throughout the chapters of various topics covered in courses, including linear progressions, harmonic Stufen, unfolding of intervals, and interruption technique. If subsequent printings of the book included an additional appendix or index of terms, teachers and students could quickly locate discussions of these devices and their graphic depictions within the context of specific compositions.

[11] One small problem with the book concerns the sizing of elements in some of the graphics, particularly Roman numerals and figured-bass symbols, which are consistently too large for their context. Many of the musical examples, which range from two-chord illustrations of specific resolutions to deep-middleground sketches of whole movements, are easily legible and elegantly drawn. However, most Roman numerals beneath the score are at least twice the size of the font used for the text of the book, and these occasionally appear alongside figured-bass symbols that are much smaller than expected. (This can be seen in Example 1, where Roman numerals beneath the score are more than twice the size of scale degrees.) I would suggest a more careful treatment of font size in subsequent printings.

[12] Another issue concerns Wen’s discussion, in chapter 5, on metric organization at the outset of the first movement of Mozart’s Symphony no. 40 in G minor, K. 550. Although metric organization is far from the only aspect of the piece that Wen discusses in this chapter, it struck me as odd that he did not cite or respond to Lerdahl and Jackendoff’s (1983) discussion of this work. Published nearly 35 years ago, A Generative Theory of Tonal Music remains a staple in the area of rhythm and meter studies, and Lerdahl and Jackendoff’s analysis of the Mozart—one of their first extended musical examples in the text—is well known among music theorists (1983, 22–25).

[13] In all, Structurally Sound: Seven Musical Masterworks Deconstructed is a well-written textbook by a learned musician practicing his craft. The analyses are clearly argued, and Wen projects a reassuring sense of authenticity in his approach to tonal music analysis. The book will be of interest to many musicians, especially those focused on Schenkerian theory and analysis. I believe the book will be a welcome addition to the range of teaching manuals on the subject.

Michael Baker

University of Kentucky School of Music

105 Fine Arts Building

Lexington, KY 40506-0022

mrbake00@uky.edu

Works Cited

Alegant, Brian. 2014. “On ‘Scuba Diving,’ or the Advantages of a Less-is-More Approach.” In Engaging Students: Essays in Music Pedagogy 2. E-book accessed January 1, 2018, http://www.flipcamp.org/engagingstudents/.

Beach, David and Yosef Goldenberg. 2015. Bach to Brahms: Essays on Musical Design and Structure. University of Rochester Press.

Cadwallader, Allen, and David Gagné. 2010. Analysis of Tonal Music: A Schenkerian Approach. 3rd edition. Oxford University Press.

Damschroder, David. 2017. Tonal Analysis: A Schenkerian Perspective. Norton.

Lerdahl, Fred, and Ray Jackendoff. 1983. A Generative Theory of Tonal Music. MIT Press. Reprinted in 1996 with minor corrections.

Schachter, Carl. (1981) 1999. “Motive and Text in Four Schubert Songs.” In Aspects of Schenkerian Theory, ed. David Beach, 61–76. Yale University Press. Reprinted in Unfoldings: Essays in Schenkerian Theory and Analysis, ed. Joseph N. Straus, 209–20. Oxford University Press.

—————. 2016. The Art of Tonal Music Analysis: Twelve Lessons in Schenkerian Theory, ed. Joseph N. Straus. Oxford University Press.

Schenker, Heinrich. (1921) 2015. Piano Sonata in A Major, Op. 101, trans. and ed. John Rothgeb. Vol. 4 of Beethoven’s Last Piano Sonatas: An Edition with Elucidation. Oxford University Press. Originally published as Sonate A Dur, op. 110. Vol. 4 of Die letzen fünf Sonaten von Beethoven (Erläuterungsausgabe). Universal Edition.

—————. 1935. Der freie Satz. Vol. 3 of Neue musikalische Theorien und Phantasien. Universal Edition.

Snodgrass, Jennifer. 2016. “Integration, Diversity, and Creativity: Reflections on the ‘Manifesto’ from the College Music Society.” Music Theory Online 22 (1).

Stein, Deborah, ed. 2005. Engaging Music: Essays in Music Analysis. Oxford University Press.

Footnotes

1. The works studied are the Air from Bach’s Orchestral Suite no. 3 in D, BWV 1068; the Andante con moto tranquillo from Mendelssohn’s Piano Trio no. 1 in D Minor, op. 49; Schubert’s “Nacht und Träume,” D. 827; the first movement of Haydn’s Symphony no. 94 in G, Hob. I: 94; the first movement of Mozart’s Symphony no. 40 in G Minor, K. 550; the funeral march of Beethoven’s Symphony no. 3 in E-flat (“Eroica”), op. 55; and the Un poco presto e con sentimento from Brahms’s Violin Sonata no. 3 in D minor, op. 108.

Return to text

2. For more information on the CMS Manifesto and its implications for collegiate music instruction, see Snodgrass 2016.

Return to text

3. This pun was the title of a special session at the 34th annual meeting of the Society for Music Theory, which took place in Minneapolis on October 27–30, 2011. The program is available at https://societymusictheory.org/sites/default/files/SMT_2011_program_book.pdf.

Return to text

4. Schachter points out the descending – within Schubert’s “Der Tod und das Mädchen,” D. 531 (1999, 213–15).

Return to text

5. A recent publication by Carl Schachter (2016) is explicitly organized in this manner.

Return to text

Copyright Statement

Copyright © 2018 by the Society for Music Theory. All rights reserved.

[1] Copyrights for individual items published in Music Theory Online (MTO) are held by their authors. Items appearing in MTO may be saved and stored in electronic or paper form, and may be shared among individuals for purposes of scholarly research or discussion, but may not be republished in any form, electronic or print, without prior, written permission from the author(s), and advance notification of the editors of MTO.

[2] Any redistributed form of items published in MTO must include the following information in a form appropriate to the medium in which the items are to appear:

This item appeared in Music Theory Online in [VOLUME #, ISSUE #] on [DAY/MONTH/YEAR]. It was authored by [FULL NAME, EMAIL ADDRESS], with whose written permission it is reprinted here.

[3] Libraries may archive issues of MTO in electronic or paper form for public access so long as each issue is stored in its entirety, and no access fee is charged. Exceptions to these requirements must be approved in writing by the editors of MTO, who will act in accordance with the decisions of the Society for Music Theory.

This document and all portions thereof are protected by U.S. and international copyright laws. Material contained herein may be copied and/or distributed for research purposes only.

Prepared by Tahirih Motazedian, Editorial Assistant

Number of visits:

6848