Koch, Carpani, and Momigny: Theorists of Agency in the Classical String Quartet?*

Edward Klorman

KEYWORDS: agency, Carpani, conversation, Hauptstimme, Haydn, Koch, Momigny, Mozart, multiple agency, Schulz, string quartet, Sulzer, texture

ABSTRACT: This study examines historical writings about the “Classical” string quartet, a genre often compared to artful conversation. The conversation metaphor implicitly suggests “multiple agency” (Klorman 2016), whereby the four parts (or players) are interpreted as representing independent characters or personas. This paradigm contrasts sharply with the more monological musical personifications advanced in many recent writings on musical agency, such as Cone’s influential The Composer’s Voice (1974), which posit a “central intelligence” representing the “mind” of the composition, its fictional protagonist, or its composer. Focusing principally on discussions of Haydn’s and Mozart’s quartets in H. C. Koch’s Versuch (1793), J. J. de Momigny’s Cours complet (1806), and G. Carpani’s Le Haydine (1812), I examine whether instrumental personas postulated by each author constitute genuine agents, according to criteria developed in Monahan 2013. At issue is whether personas are described as possessing (1) such anthropomorphic qualities as sentience, volition, and emotion; and (2) a capacity for independent action or utterance.

DOI: 10.30535/mto.24.4.3

Copyright © 2018 Society for Music Theory

Introduction

Example 1. Mozart, Piano Quartet in E-flat major, K. 493, Allegretto (III), mm. 129–40

(click to enlarge and listen)

[0.1] In late-eighteenth-century chamber music, there are certain passages that seem so vividly to enact a delightful exchange among familiars that it can be difficult not to hear them in these terms (Example 1).

[0.2] Indeed, the coquettish interplay between piano and violin seems to give this passage its raison d’être. The many historical authors who compared chamber music—and especially string quartets—to artful conversation seem to have been responding to just this sort of interplay. The distribution of material among the parts, the interchanges among gestures that seem to assert and riposte, the hierarchy of leading and following roles—these musical features all resemble aspects of social intercourse.

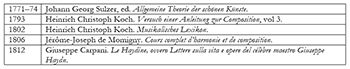

Table 1. Major Historical Sources Under Study

(click to enlarge)

[0.3] Accounts of musical “conversation” have commonly equated the instrumental parts with individual characters or personas. But what precisely is the nature of these characters as imagined by historical authors? Did these writers conceive of a stylized “conversation” among fictional personas that they imagine in the music, or among the literal, real-world players, or perhaps among some conflation of these concepts? And, most importantly, do their writings imbue these characters with agency? This study examines elements suggestive of musical agency in writings about string quartets by Giuseppe Carpani, Heinrich Christoph Koch and Jérôme-Joseph de Momigny, among a few others discussed in passing along the way. Table 1 provides a chronological list of the primary sources under examination. The Appendix provides original, foreign-language text of excerpts that are quoted here in translation.(1) Interspersed within this historical study are two short analytical interludes that are loosely inspired by ideas from these authors.

[0.4] To speak of music in terms of fictional personas or characters is not necessarily to speak of musical agency. Some working definition of “agency” will therefore be needed as a yardstick against which to examine various historical texts. I will adopt Seth Monahan’s (2013) formulation from his lucid meta-study of musical agency. Monahan defines as agential those explanations of musical events that appeal to “psychodramatic or anthropomorpic grounds” and that “regard musical objects or gestures as volitional, as purposive, in such a way that is indicative of psychological states,” ascribing “sentience” to musical works or objects (324–26).

[0.5] Authors in what might be called the Edward T. Cone tradition have tended toward monological ascriptions of agency—as in Cone’s (1974) “composer’s voice” and “complete work-persona,” a unitary, controlling “central intelligence” understood to represent the “mind” of the composition (106).(2) But the sources examined in this study draw attention to lower-level agents, that is, to the characters within a composition who are said to be engaged in conversation or social intercourse. In Klorman 2016, I adopted the term “multiple agency” to designate such interpretations, which focus on multiple characters (often represented by individual instrumental parts) who are described as possessing a capacity for autonomous actions and utterances. Multiple agency requires not only agential autonomy between melody and accompaniment but moreover a capacity for the exchange of melodic and other roles among the various personas.(3) In short, this study aims to integrate theories of agency and texture.

I. Heinrich Christoph Koch (and His Circle)

[1.1] In eighteenth-century German writings, the term “sonata” refers to any small-ensemble piece composed for one player per part, that is, what today is called “chamber music.”(4) Koch’s discussion of diverse forms of sonata finds its basis in earlier writings included in Johann Georg Sulzer’s (1771–74) Allgemeine Theorie der schönen Künste. The entry on “sonatas,” which was probably penned by J. A. Peter Schulz,(5) emphasizes their capacity to express any character or expression:

There is no form of instrumental music that is more capable of depicting wordless sentiments than the sonata. The symphony and overture have a somewhat more fixed character, while the form of a concerto seems suited more for providing a skilled performer the opportunity to be heard and accompanied by many instruments than for the depiction of passions. Other than these (and dances which also have their own character), no form other than the sonata may assume any character and every expression. In a sonata, the composer might want to express through the music a monologue marked by sadness, misery, pain, or of tenderness, pleasure and joy; using a more animated kind of music, he might want to depict a passionate conversation between similar or complementary characters; or he might wish to depict emotions that are impassioned, stormy, or contrasting, or ones that are light, delicate, flowing, and delightful.(6) (Sulzer and Koch 1996, 103–4) [See original text, Appendix Document #9.]

[1.2] As exemplars of such musical conversations, Schulz enthusiastically recommends C. P. E. Bach’s trio sonatas, and he reserves special praise for the Trio Sonata in C minor, H. 579, in which the two violins represent the temperaments of Sanguine and Melancholy, respectively.(7) It should be noted that this conception of Bach’s trio sonata interprets a conversation limited to the melodic, treble parts. The bass retains its traditional accompanimental (or foundational) role, more a part of the scenery than one of the characters; it may be physically present and fulfilling an important function, but it does not quite “count.”(8) This facet distinguishes Schulz’s perspective from later notions of musical “conversation” and from my multiple agency, in which every note in every part is regarded as an utterance by some anthropomorphic persona.

[1.3] Writing about a generation later, Koch’s discussions of sonatas in his Versuch einer Anleitung zur Composition (vol. 3, 1793) and in his Musikalisches Lexikon (1802) borrow liberally from Sulzer and Schulz. But whereas Schulz had written that a sonata might be construed as either a monologue or dialogue, Koch offers the following criteria to distinguish between these two paradigms:

In the two-voiced sonata in which a Hauptstimme is accompanied by a bass part [Grundstimme], that is, in which only a [single] Hauptstimme exists, only the passions [Empfindungen] of a single person are conveyed. But in the two-, three- or four-voiced sonata in which two, three, or four Hauptstimmen exist, the passions of exactly that many individual people are conveyed . . . .

The sonata comprehends various categories—designated by the terms solo, duet, trio, quartet, and so on—according to the number of different parts and the diverse manner of handling these parts, in so far as they assert themselves as Hauptstimmen.(9) (Koch 1802, cols. 1415 n. and 1417) [See original text, Appendix Document #3.]

[1.4] Whereas Schulz had understood a sonata (i.e., any kind of chamber music) to be a conversation among all parts other than the bass line (which he automatically regards as a mere Grundstimme), Koch describes how a sonata can represent any number of individuals, exactly equal to the number of Hauptstimmen. Koch’s more modern conception betrays a shift in musical style regarding the bass part at the twilight of the thoroughbass era.(10) By the time of Koch’s writing in 1802, the bass part had emerged from its former accompanimental role and had been honored as a legitimate obbligato voice. No longer made to dine with the servants, the bass was now invited to join the party and mingle freely with the other guests.

[1.5] The term “Hauptstimme” appears regularly in both singular and plural forms in Sulzer’s and Koch’s writings; for them, it was not an exclusive status (as it was for Schoenberg). Koch regards Hauptstimme status as essentially tantamount to personhood. He states this explicitly in his entry for “Hauptstimme” in his Musikalisches Lexikon. Discussing various categories of texture, he writes that a homophonic (homophonisch) composition is one “in which the individual sentiment of a single person [individuelle Empfindungsart eines einzigen Menschen] is expressed by the means of a single Hauptstimme,” whereas polyphonic (polyphonisch) denotes one “in which the composer expresses the sentiment[s] of various people [die Empfindung verschiedener Menschen] through multiple Hauptstimmen” Koch 1802, col. 749). Such a definition begins to adumbrate the anthropomorphism and psychological capacities of Monahan’s agents and the potential for my multiple agency.

[1.6] Turning now to Koch’s treatment of string quartets specifically: like so many manuals of artful conversation, Koch’s discussion of quartets is concerned with resolving certain tensions inherent in any social intercourse—that is, with reconciling hierarchy and equality through the harmonious exchange of roles among the participants:

If [the quartet] is truly to consist of four obbligato voices, of which none can claim the privilege [Vorrecht] of being the [sole] Hauptstimme, then it can only be treated in the manner of a fugue.

But since the modern quartet is written in the Galant style, one must content oneself with there being four Hauptstimmen of a particular kind that exchange being dominant [vier solchen Hauptstimmen, die wechselweise herrschend sind] and of which now one, now another takes the customary Galant-style bass.

While one of these voices is busy playing the main melody [Hauptmelodie], the two others [those not playing the Hauptmelodie or bass] must play accessory melodies [zusammen hängenden Melodien] that enhance the expression without obscuring the main melody. From this, it is evident that the quartet is one of the most difficult types of compositions. It should be ventured only by a composer who is both fully trained and experienced in many musical textures [Ausarbeitungen].

Among recent composers in this genre of sonatas, Haydn, Pleyl [sic], and Hofmeister [sic] have provided the public with the greatest riches. But among all the modern four-part sonatas, the six quartets for two violins, viola, and cello by the late Mozard [sic], published in Vienna with a dedication to Haydn, best embody the idea of a true quartet. They are unique in their special mixture of strict and free style and in their treatment of harmony.(11) (Koch 1793, 325–27) [See original text, Appendix Document #2.]

[1.7] Recognizing the incompatibility of strict fugal treatment with galant aesthetics, Koch settles for a non-fugal texture but, significantly, one in which all four parts are designated as Hauptstimmen. Koch’s four paradigmatic roles are described as fully exchangeable.(12) Never does he state, for instance, that the first violin has the melody most of the time. Instead, he emphasizes the constant interchanging of roles.

[1.8] In a later version of the same discussion, published in his Musikalisches Lexikon, Koch largely repeats this same commentary but with one significant added detail: he describes a string quartet as comprising not just four Hauptstimmen but four concertirende (or “concerting”) Hauptstimmen.(13) In Koch’s usage, “concertirend” refers to an obbligato instrument that asserts itself against the main melody part “in order to compete [wettstreiten]” (Koch 1802, s.v. “Concertirend”).(14) For Koch, this sense of friendly competition (Wettstreit) seems to motivate the constant role exchange within a quartet. Koch is not alone in this competitive notion. Schulz had described a “true trio” as having “three Hauptstimmen concerting against one another [die gegen einander concertiren] and have, as it were, a conversation in tones” (Sulzer 1771–74, s.v. “Trio”).(15) A similar sense of friendly competition or one-upmanship is expressed in many historical manuals of artful conversation, which describe social intercourse as a game or sport that can be won by the wittiest player.(16)

[1.9] In summary, Koch’s discussion of sonatas and quartets hints at several key elements of Monahan’s definition of agency. Koch’s equation of Hauptstimme status with personhood and his concept of hierarchical role exchange among these Hauptstimmen suggests notions of anthropomorphism, sentience, and capacities to express their respective sentiments (Empfindungen) or even to engage in competition (Wettstreit).

II. Analytical Interlude: A Neo-Kochian Analysis of Mozart’s Quartet in G major, K. 387 (IV)

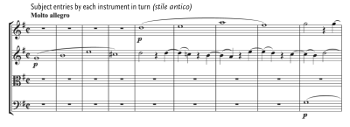

Example 2. Mozart, Quartet in G major, K. 387, Molto allegro (IV), mm. 1–51

(click to enlarge and listen)

[2.1] To engage in a bit of fantastical extrapolation, what might a neo-Kochian analysis of a Mozart quartet passage look like? Since he so admired Mozart’s “Haydn” quartets for their mixture of the fugal and free styles, I will examine a passage from the finale of the Quartet in G major, K. 387 (Example 2).

[2.2] The movement opens in stile antico, with each instrument entering in turn with overlapping statements of a five-measure fugal subject. Suddenly (m. 17) the first violin changes the topic, breaking out into a flurry of virtuoso fiddling, to which the remaining parts provide a simple, chordal accompaniment. Not wanting to be outdone, the second violin immediately jumps in (m. 23), repeating its colleague’s statement exactly in a moment of “anything you can do, I can do better.”

[2.3] Soon the viola chimes in (m. 29), though somewhat less virtuosically, echoing just the passage’s tail. But the cello, who is the quartet’s resident expert in the harmonic/cadential plan of sonata form, seems to be fed up with this time-consuming rivalry, which has delayed the necessary modulation to the subordinate key by keeping the movement locked in a tonic-key holding pattern. And so the cello barges in (m. 31), subito forte, turning the fiddling figure into the model for a sequence that leads the way toward the new key, achieving a half cadence (m. 39) and standing-on-the-dominant that prepares for his statement of the subordinate theme in m. 51.(17)

[2.4] The foregoing analysis interprets musical events, such as changes of musical topic or exchanges of textural roles, as the purposive actions of the four instrumental parts. These parts are treated here as fictional characters enacted by the four players in a performance of the passage, as in my (2016) notion of multiple agency.

III. Giuseppe Carpani

[3.1] Compared to the restraint of the eighteenth-century German sources examined above, the nineteenth-century French and Italian sources to which I now turn are striking for their more vividly anthropomorphic interpretations. This probably reflects both national differences (since opera reigned supreme in France and Italy) and a nascent tendency toward hermeneutic approaches among early nineteenth-century musical writers (Bent 1994).

[3.2] Carpani’s conception of roles within the string quartet makes a sharp contrast to Koch’s:

A friend of mine imagined, in listening to a quartet of Haydn, that he was witnessing a conversation of four amiable people. I always liked this idea, as it very much resembles the truth. It seemed to him that he recognized in the first violin a man of spirit and affability, middle aged, a good speaker [parlatore], who sustained the major part of the discourse, which he himself initiated and animated.

In the second violin, he recognized a friend of the first, who sought in every way to make him shine [farlo comparire], rarely taking turns for himself [occupandosi rare volte di se stesso], and intent on sustaining the conversation more by agreeing to what he heard from the other [violin] than with his own ideas.

The Bass [basso, i.e., cello] was a solid man, learned, and sententious. Bit by bit he went along supporting the discourse of the first violin with laconic but confident statements [sicure sentenze], and occasionally—as a prophet, a man well experienced in the knowledge of things —predicted what the principal speaker [l’oratore principale] would have said and gave strength and direction [norma] to what was said.

The viola, then, seemed to him a somewhat loquacious matron, who actually did not have very important things to say but nonetheless wanted to intrude [intromettersi] into the discourse and seasoned the conversation with her grace and sometimes with delightful chattering [cicalate] that gave the others a chance to take a breath; in the rest [of the time], she was more the friend of the Bass than of all the other interlocutors.(18) (Carpani 1812, 96–97) [See original text, Appendix Document #1.]

[3.3] Whereas Koch discusses features he regards as intrinsic qualities of quartets, Carpani explicitly describes his four characters as fictional personas imagined by his friend. Carpani’s characters are perhaps comparable to commedia dell’arte archetypes, who retain their stock roles from quartet to quartet. And the word “characters” seems truly apt; unlike Koch’s neutral “Hauptstimmen,” Carpani’s personas are more richly anthropomorphic and are imbued with such human attributes as age, gender, personality, and even a capacity for romantic affections.(19)

[3.4] Whereas Koch describes an egalitarian interplay, Carpani’s roles are fixed in a strict hierarchy, seemingly determined by each instrument’s relative prominence in the melodic action.(20) (This is but one reason he dismisses the poor viola, which is generally the least melodic instrument among the four.) Carpani appears to equate only melodic utterance with speech, implying that accompanimental parts are something else that remains undefined. This marks a sharp contrast with Koch’s interest in and careful attention to simultaneous roles within a texture.

IV. Analytical Interlude: A Neo-Carpanian Analysis of Haydn’s Quartet in G major, op. 77, no. 1 (I)

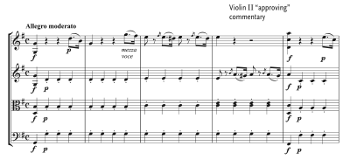

Example 3a. Haydn, Quartet in G major, op. 77, no. 1, Allegro moderato (I), mm. 1–29

(click to enlarge and listen)

Example 3b. Hypothetical recomposition (with

(click to enlarge)

[4.1] As this quartet begins, the first violin introduces the main melodic idea, supported by leggiero chords from the others and occasional “approving” commentary figures from the second violin (mm. 4 and 8), which endorse the first violin’s statements without adding anything original (Example 3a). The cello introduces certain salient accidentals throughout the excerpt, notably the

[4.2] After the opening returns in m. 14, notable accidentals are introduced in m. 16 by the second violin (

VI. Jérôme-Joseph de Momigny

Example 4. Facsimile of Momigny’s analysis/arrangement of Mozart’s Quartet in D minor, K. 421 (Plate 30 from Momigny 1806, first page only)

(click to enlarge and listen)

Example 4b. Performance of Momigny’s analysis/arrangement

(click to watch)

[5.1] Momigny’s famous analysis of Mozart’s Quartet in D minor, K. 421, takes the form of a coloratura arrangement supplied with original French verse about Dido and Aeneas.(23) His massive (ten-staff!) musical score spans forty-some pages, and his accompanying prose discussion of the example is over thirty, thus representing a significant portion of his treatise. Momigny’s score shows Mozart’s original quartet in the upper systems and a vocal–piano arrangement toward the bottom.(24) The first page of Momigny’s score is shown in Example 4a; a complete facsimile can be downloaded here. The video in Example 4b provides a performance of Momigny’s analysis—in a version for soprano with strings—with a scrolling score.

[5.2] Momigny explains his inspiration and rationale as follows:

The style of this Allegro Moderato is noble and pathetic. I decided that the best way to have my readers recognize its true expression was to add words to it . . . .

I thought I perceived that the feelings expressed by the composer were those of a lover who is on the point of being abandoned by the hero she adores: Dido, who had had a similar misfortune to complain of, came immediately to mind. Her noble rank, the intensity of her love, the renown of her misfortune—all this convinced me to make her the heroine of this piece.(25) (Momigny [1806] 1998, 827) [See original text, Appendix Document #4.]

[5.3] Departing from the tradition of comparing quartets to conversation, Momigny’s “Dido” arrangement locates the emotive personification in a single persona represented by the first violin part. But what, then, do the other three parts represent for Momigny? His arrangement renders the movement as an aria con pertichino, since Dido’s affecting soliloquy is interrupted by a momentary appearance by Aeneas, portrayed by the cello in the exposition, mm. 19–21 (Example 5a, see boxed material).(26) At the end of the exposition, there is a very brief appearance of a chorus, portrayed by the lower three instruments, which makes two lamenting statements of “hélas” in mm. 39–40 (Example 5b, see boxed material).

Example 5a. Anomalies in Momigny’s Text Underlay. Commentary by Aeneas (Enée), mm. 17–22 (click to enlarge and see the rest) | Example 5b. Anomalies in Momigny’s Text Underlay. Choral statements, mm. 38–41 (click to enlarge and see the rest) |

Example 5c. Anomalies in Momigny’s Text Underlay. End of coda untexted (after Dido dies), mm. 114–17

(click to enlarge and see the rest)

[5.4] Save for these fleeting statements by Aeneas and the chorus (both in the exposition), Momigny’s added verse is otherwise limited to the first violin part, which is texted almost entirely throughout. Only the final two measures of the movement are left without added text (Example 5c). This stands to reason: after Dido’s dying statement (“je le sens; je meurs”), a final “orchestral” tutti seems only appropriate.

[5.5] In casting the first violin as the spurned Queen of Carthage and treating it as essentially the only part outfitted with verse, Momigny establishes the first violin as the unequivocal protagonist, implicitly relegating the others to the orchestra pit. The notation of Momigny’s score underscores a categorical difference between the first violin and the other parts. In the bottom two staves, the first violin part is given in vocal notation (with underlaid text and syllabic beaming), while the others are absorbed into the homogeneous piano accompaniment, relinquishing their individual integrity.

[5.6] But Momigny shows considerable discomfort with the rigid division between the first violin and the other instruments implied by his operatic premise. Early in his discussion of the piece, in a fascinating passage labeled “Petite digression sur les Accompagnemens,” he expresses ambivalence about the status of the lower three parts:

Each party in the accompaniment can, by turns, play the role of interlocutor; but, more often, the accompanying parts [accompagnemens](27) are nothing but the diverse parts of the same individual of which the vocal part [chant](28) is the face [figure]. What this face (which should never be insignificant) cannot say all by itself, even with the very powerful aid of words, the accompanying instruments assist in expressing. Sometimes they trace in their own way the setting of the scene; finally, they bring back under the eyes of the listener, or, less figuratively, they recall to his mind, by means of the ear, anything that can make him take a greater interest in what is presented to him. Above all, they depict the state where the actor* finds himself, his calm, his agitation, his outbursts, his pain, his pleasures, his sadness, his joy, his indifference, his love or his hatred. On occasion, they seem to form the retinue of a great personage, a hero’s entourage. Based on this, one cannot doubt that a good opera will make a greater impression than a tragedy of equal strength that is only spoken, assuming however that the listeners are equally capable of understanding them.(29) (Momigny 1806, 1:374) [See original text, Appendix Document #5.]

* [Momigny’s footnote:] The word “actor” is not used here to mean he who represents in a theater something that supposedly takes place elsewhere; rather, it signifies he who takes action.

[5.7] Momigny’s discussion anticipates some challenging narratological questions that would be taken up nearly two centuries later in Cone 1974. Within the brief aside, Momigny wanders in circles, vacillating between two conflicting notions: (1) that the accompanying instruments are part of the Dido’s vocal persona, or (2) that the accompanying instruments are themselves individual personas, capable of independent action and utterance. Momigny contradicts himself even within the first sentence, which begins by positing the accompagnemens as the protagonist’s interlocutors but curiously concludes instead that they more typically are parts of the protagonist’s own body. The latter formulation conjures an evocative metaphor: the vocal part (chant) is the protagonist’s face (the locus of expression and the only part of the body that is capable of speech or song), yet a face requires a body below it (les accompagnemens) to support basic life functions and to enhance its expression through gesture and body language. It is significant that Momigny regards only the vocal persona as a genuine acteur, a term that (according to his footnote) is roughly equivalent to Cone’s or Monahan’s “agent.”(30)

Example 6. Momigny’s analysis. Development (excerpt) mm. 45–62

(click to enlarge and see the rest)

[5.8] This approach serves Momigny well in the relatively homophonic exposition and recapitulation, but it poses challenges in the more contrapuntal development. The passage quoted in Example 6 illustrates: Momigny offers a detailed account of the exchanges in mm. 46–49 between the viola and cello and between the pair of violins. Yet, the intimacy of the violins’ chain of “leapfrogging” suspensions notwithstanding, only the first violin is provided text in his musical score.(31) Indeed, Momigny’s commitment to treating the first violin as Dido and his reticence to provide text to other parts even when they come to the fore lead to some curious solutions. A particularly telling moment is m. 53, where the first violin’s rest is provided a syllable of text (!) while the viola solo remains textless.(32) Momigny proffers an imaginative explanation of this juncture:

How the anger of the queen of Carthage bursts out in the music of the third musical verse [mm. 50ff.]! and how the last syllable of the word amour is felicitously placed on theB♭ [m. 51], in order to express the grief that Dido feels at having rashly abandoned herself to this passion for a perjurer! The second time she repeats this word she cannot finish it [upbeat to m. 53], because she is choked by the grief that overwhelms her. It is here that the viola part, which represents her sister or confidante, takes up the word to address the Trojan the reproaches that Dido no longer has the strength to make herself.(33) (Momigny [1806] 1998, 830) [See original text, Appendix Document #6.]

[5.9] Momigny’s account is compelling on its own dramatic terms. But if m. 53 represents Dido’s sister “tak[ing] up the word” while Dido herself is too anguished to speak further, why is the viola not outfitted with text (as the cello had been in Example 5a)? An unresolved dissonance remains between Momigny’s prose discussion and his musical score: the former suggests that the viola in m. 53 represents a human character, whereas the latter decidedly does not.

[5.10] This problem obtains throughout the development, which is rife with contrapuntal exchange. In precisely the sort of passages in which Koch would have emphasized interplay between the Hauptmelodie and accessory melody roles, Momigny mentions the contrapuntal imitations in his analytical prose but dutifully (or stubbornly) continues to underlay only the first violin part with text in his score. Some odd musical settings result from his fidelity to this paradigm, whereby virtually every note in the first violin part is regarded as an utterance by Dido but melodic statements by other instruments are ignored. For instance, in mm. 60 and 62, the second violin melodies are overlooked while Dido is made to demean herself with “patter” ill-suited to her noble station. The rigidity of Momigny’s roles and his fixed attention to the first violin call to mind the home video of an elementary-school play as recorded by a stage parent who focuses so steadfastly on their own child (who plays the lead role) that they blithely leave other children out of the frame, even when they are speaking.(34)

[5.11] Indeed, whenever the music turns contrapuntal, Momigny’s commentary downplays or drops the Dido story and simply describes the intricacies of textural and motivic exchange in technical, musical terms. Evidently, Momigny’s aria paradigm works only up to a point and, without explicitly saying so, he reverts to Koch-like commentary as needed when roles are exchanged in contrapuntal passages. The lesson of Momigny’s experiment should have been obvious to him from the start, namely, that the roles within a string quartet are enacted less literally and are less robust than those in an opera or a play.

VI. Conclusions

[6.1] To what extent do the authors examined in this study invoke notions of agency in their accounts of Haydn and Mozart string quartets? Surely Momigny comes the closest. To readers of Cone-influenced narratological analyses of Schubert, Beethoven, or Mahler, Momigny’s interpretation of Mozart’s quartet as Dido’s lament may read as a somewhat familiar form of emotive personification. His musings over the ontological status of the accompanimental parts aside, his interpretation is essentially a unitary one; the expressive statements he imputes to Dido are identical with what he understands the quartet as a whole to be expressing.

[6.2] Carpani’s brief discussion, included within a biography rather than a musical treatise, is more of an anecdote or witticism than any kind of musical theory. This passage quoted from his text is probably best interpreted as one among many statements, dating from around the emergence of the string quartet to the present, that have compared that genre to artful conversation.

[6.3] To interpret Koch’s writings as incorporating elements of musical agency requires some considerable extrapolation. But some readers may be surprised to encounter in his writings a nascent concept of persona implicit in his discussions of musical textures and the interaction of instrumental parts, including explicit criteria for interpreting multiple, autonomous personas versus monological, all-controlling ones. Specifically, his equation of Hauptstimme status with personhood satisfies Monahan’s requirements of sentience, anthropomorphism, and a capacity to express sentiments—even if these elements are considerably more understated in his writings than in Carpani’s or Momigny’s bolder, more fantastical, and more psychodramatic intepretations.

[6.4] But Koch’s most important contribution is his (characteristically Germanic) attention to all strands within the texture and the interplay among their simultaneous and successive utterances. Koch’s focus on such interchange accords closely with what the venerable Enlightenment salon hostess Madame de Staël characterized as “the spirit of conversation”:

That sort of pleasure, which is produced by an animated conversation, does not precisely depend on the nature of that conversation; the ideas and knowledge which it develops do not form its principal interest; it is a certain manner of acting upon one another, of giving mutual and instantaneous delight, of speaking the moment one thinks, of acquiring immediate self-enjoyment, of receiving applause without labor, of displaying the understanding in all its shades by accent, gesture, look; of eliciting, in short, at will, the electric sparks.(35) (Staël 1861, 77–78)

APPENDIX OF HISTORICAL DOCUMENTS CITED

This appendix provides the original text of foreign-language sources quoted in English translation throughout the article. Documents are numbered alphabetically by the author’s surname, and then chronologically by date of publication or by place within a single publication. Archaic spellings are preserved; the notation “sic” is reserved for misspellings. For the German texts, Sperrdruck in the original source is rendered here as italic type, and roman font in the original is indicated with underlined text. Numbers within braces (e.g., {1}) indicate page or column breaks in the original source.

Document #1: Carpani 1812, 96–97.

Un amico mio s’immaginava nell’udire un quartetto d’Haydn d’assistere ad una conversazione di quattro amabili persone e questa idea mi è sempre piaciuta, perché molto si avvicina al vero. Sembrava a lui di riconoscere nel violino primo un uomo di spirito ed amabile, di mezza età, bel parlatore, che sosteneva la maggior parte del discorso da lui stesso proposto ed animato Nel secondo violino riconosceva un amico del primo, il quale cercava per ogni maniera di farlo comparire, occupandosi rare volte di {97} se stesso ed intento a sostenere la conversazione più coll’adesione a quanto udiva dall’altro che con idee sue proprie Il Basso era un uomo sodo, dotto e sentenzioso. Questi veniva via via appoggiando con laconiche, ma sicure sentenze il discorso del violino primo, e talvolta da profeta, come uomo sperimentato nella cognizione delle cose, prediceva ciò che avrebbe detto l’oratore principale, e dava forza e norma ai di lui detti. La viola poi gli sembrava una matrona alquanto ciarliera, la quale non aveva per verità cose molto importanti da dire ma, pure voleva intromettersi nel discorso e colla sua grazia condiva la conversazione, e talvolta con delle cicalate dilettose dava tempo agli altri di prender fiato. Nel rimanente più amica del Basso che degli altri interlocutori.

Document #2: Koch 1793, 325–27.

(N.b.: See also a later version of this essay that appears in Koch 1802, s.v. “Quatuor.”)

Von dem Quatuor.

§. 118. Das Quatuor, anjezt das Lieblingsstück kleiner musikalischen Gesellschaften, wird von den neuern Tonsetzern sehr fleitzig bearbeitet.

{326} Wenn es wirklich aus vier obligaten Stimmen bestehen soll, von denen keine der andern das Vorrecht der Hauptstimme streitig machen kann, so muß der Hauptstimme streitig machen kann, so muß es nach Art der Fuge behandelt werden.

Weil aber die modernen Quartetten in der galanten Schreibart gesezt werden, so muß man sich an vier solchen Hauptstimmen begnügen, die wechselweise herrschend sind, und von denen bald diese, bald jene den in Tonstücken von galantem Stiele [sic] gewöhnlichen Baß macht.

Während aber sich eine dieser Stimmen mit dem Vortrage der Hauptmelodie beschäftiget, müssen die beyden andern, in zusammen hängenden Melodien, welche den Ausdruck begünstigen, fortgehen, ohne die Hauptmelodie zu verdunkeln. Hieraus siehet man, daß das Quatuor eine der allerschweresten Arten der Tonstücke ist, woran sich nur der völlig ausgebildete, und durch viele Ausarbeitungen erfahrne Tonsetzer wagen darf.

Unter den neuern Tonsetzern haben Haydn, Pleyl [sic] und Hofmeister am mehresten das Publikum mit dieser Gattung der Sonaten bereichert. Auch der sel. Mozard [sic] hat in Wien sechs Quartetten für zwey Violinen, Viole und Violoncell unter einer Zuschrift an Haydn stechen lassen, die unter allen modernen vierstimmigen {327} Sonaten, am mehresten dem Begriffe eines eigentlichen Quatuor entsprechen, und die wegen ihrer eigenthümlichen Vermischung des gebundenen und freyen Stils, und wegen der Behandlung der Harmonie einzig in ihrer Art sind.

Document #3: Koch 1802, cols. 1415 n. and 1417.

(See also an early version of this essay that appears in Koch 1793, 315–16).

Es werden nemlich in der zweystimmigen Sonate, in welcher eine Hauptstimme von einer Grundstimme begleitet wird, das ist, in welcher nur eine Hauptstimme vorhanden ist, nur die Empfindungen einer einzigen Person, in derjenigen zwey-[,] drey- oder vierstimmigen Sonate aber, in welchen zwey, drey oder vier Hauptstimmigen enthalten sind, die Empfindungen eben so vieler einzelnen Personen ausgedrückt . . . .

{1417} Die Sonate begreift nach der Anzahl der verschiedenen dabey vorhandenen Stimmen, und nach der verschiedenen Behandlungsart dieser Stimmen, in wie ferne sie sich nemlich als Hauptstimen behaupten, verschiedene Gattungen unter sich, die man mit den Namen Solo, Duett, Trio, Quartett u.s.w. bezeichnet.

Document #4: Momigny 1806, 1:371.

Du Style musical de ce Morceau.

Le style de cet Allegro Moderato est noble et pathétique. J’ai cru que la meilleure manière d’en faire connaître la véritable expression, à mes lecteurs, était d’y joindre des paroles. Mais ces vers, si l’on peut leur donner ce nom, ayant été pour ainsi dire improvisés, ne doivent être jugés sous aucun autre rapport que sous celui de leur concordance avec le sens de la musique.

J’ai cru démêler que les sentimens exprimés par le compositeur étaient ceux d’une amante qui est sur le point d’être abandonnées par le héros qu’elle adore : Didon, qui a eu à se plaindre d’un semblable malheur, est venue aussitôt à ma pensée. L’élévation de son rang, l’ardeur de son amour, la célébrité de son infortune, tout m’a décidé à faire l’héroïne de ce sujet.

Document #5: Momigny 1806, 1:374.

Petite digression sur les Accompagnemens.

Chaque partie d’Accompagnement peut jouer tour-à-tour le rôle d’interlocuteur; mais le plus souvent les Accompagnemens ne sont que les diverses parties du même individu dont le chant est la figure. Ce que cette figure, qui ne doit jamais être insignifiante, ne peut dire toute seule, même avec le secours si puissant de la parole, les Accompagnemens l’aident à l’exprimer. Tantôt ils tracent à leur manière le lieu de la scène; enfin ils remettent sous les yeux de l’auditeur, ou, pour parler sans figure, ils rappellent à son esprit, par le sens de l’oreille, tout ce qui peut lui faire prendre un plus grand intérêt à ce qu’on lui expose. Ils peignent sur-tout l’état où l’acteur (1) se trouve, son calme, son agitation, ses emportemens, sa douleur, ses plaisirs, sa tristesse, sa joie, son indifférence, son amour ou sa haine. Par fois, ils semblent former la suite d’un grand personnage, l’escorte d’un héros.

D’après cela, on ne peut douter qu’un bon opéra ne fasse plus d’impression qu’une tragédie d’égale force qui ne serait que déclamée, en supposant toutefois que les auditeurs sont également propres à bien comprendre l’un et l’autre.

[Momigny’s footnote:]

(1) Le mot acteur n’est pas pris ici pour celui qui représente au théâtre ce qui est censé arrive ailleurs, mais il signifie celui qui fait l’action.

Document #6: Momigny 1806, 2:392.

Comme l’indignation de la reine de Carthage éclate dans la Musique du troisième vers musical ! et comme la dernière syllabe du mot amour est heureusement placée sur le si

Document #7: Rousseau 1768, 394.

QUATUOR. f. m. C’est le nom qu’on donne aux morceaux de Musique vocale ou instrumentale qui sont à quatre Parties récitantes (Voyez Parties.) Il n’ya point de vr’is Quatuor, ou ils ne valent rien. Il faut que dans un bon Quatuor les Parties soient presque toujours alternatives, parce que dans tout Accord il n’ya que deux Parties tout au plus qui fassent Chant & que l’oreille puisse distinguer à la fois; les deux autres ne sont qu’un pur remplissage & l’on ne doit point mettre de remplissage dans un Quatuor.

Document #8: Staël 1813, 96–97

Le genre de bien-être que fait éprouver une conversation animée ne consiste pas précisément dans le sujet de cette conversation; les idées ni les connoissances qu’on peut y développer n’en sont pas le principal intérêt; c’est une certaine manière d’agir les uns sur les autres, de se faire plaisir réciproquement et avec rapidité, de parler aussitôt qu’on pense, de jouir à l’instant de soi-même d’être applaudi sans travail de manifester {97} son esprit dans toutes les nuances par l’accent, le geste, le regard, enfin de produire à volonté comme une sorte d’électricité qui fait jaillir des étincelles, soulage les uns de l’excès même de leur vivacité et réveille les autres d’une apathie pénible.

Document #9: Sulzer 1771–74, s.v. “Sonate,” 2:1094–95.

(N.b.: This entry was most likely penned by J. A. P. Schulz.)

SONATE. (Musik.) Ein Instrumentalstük von zwey, drey oder vier auf einander folgenden Theilen von verschiedenem Charakter, das entweder nur eine oder mehrere Hauptstimmen hat, die aber nur einfach besetzt sind: nachdem es aus einer oder mehreren gegen einander concertirenden Hauptstimmen besteht, wird es Sonata a solo, a due, a tre etc. genennet.

Die Instrumentalmusik hat in keiner Form bequemere Gelegenheit, ihr Vermögen, ohne Worte Empfindungen zu schildern, an den Tag zu legen als in der Sonate. Die Symphonie, die Ouvertüre, haben einen näher bestimmten Charakter; die Form eines Concertes scheint mehr zur Absicht zu haben, einem geschickten Spieler Gelegenheit zu geben, sich in Begleitung vieler Instrumente hören zu lassen, als zur Schilderung der Leidenschaften angewendet zu werden. Außer diesen und den Tänzen, die auch ihren eigenen Charakter haben, giebt es in der Instrumentalmusik nur noch die Form der Sonate, die alle Charaktere und jeden Ausdruck annimmt. Der Tonsetzer kann bey einer Sonate die Absicht haben, in Tönen der Traurigkeit, des Jammers, des Schmerzens, oder der Zärtlichkeit oder des Vergnügens und der Fröhlichkeit ein Monolog auszudrüken; oder ein empfindsames Gespräch in bloß leidenschaftlichen Tönen unter gleichen, oder von einander abstechenden Charakteren zu unterhalten; oder bloß heftige, stürmende, oder contrastirende, oder leicht und sanft fortfließende ergötzende Gemüthsbewegungen zu schildern. Freylich {1095} haben die wenigsten Tonsetzer bey Verfertigung der Sonaten solche Absichten, und am wenigsten die Italiäner, und die, die sich nach ihnen bilden: ein Geräusch von willkürlich auf einander folgenden Tönen, ohne weitere Absicht, als das Ohr unempfindsamer Liebhaber zu vergnügen, phantastische plötzliche Uebergänge vom Fröhlichen zum Klagenden, vom Pathetischen zum Tändelnden, ohne daß man begreift, was der Tonsetzer damit haben will, charakterisiren die Sonaten der heutigen Italiäner; und wenn die Ausführung derselben die Einbildung einiger hitzigen Köpfe beschäfftiget, so bleibt doch das Herz und die Empfindungen jedes Zuhörers von Geschmak oder Kenntniß dabey in völliger Ruhe.

Edward Klorman

Schulich School of Music

McGill University

555 rue Sherbrooke O

Montréal, QC H3A 1E3, Canada

edward.klorman@mcgill.ca

Works Cited

Baillot, Pierre. 1839. “Caractère des divers instrumens de Musique.” Unpublished manuscript. Bibliothèque national de France (F-Pn, Fond Madeleine Panzera-Baillot, Souvenir II), 2–3.

Bent, Ian. 1994. Hermeneutic Approaches. Vol. 2 of Music Analysis in the Nineteenth Century. Cambridge University Press.

Burke, Peter. 1993. The Art of Conversation. Cornell University Press.

Byros, Vasili. 2012. “Meyer’s Anvil: Revisiting the Schema Concept.” Music Analysis 31 (3): 273–346.

Caplin, William E. 2004. “The Classical Cadence: Conceptions and Misconceptions.” Journal of the American Musicological Society 57 (1): 51–117.

Carpani, Giuseppe. 1812. Le Haydine, ovvero Lettere sulla vita e opere del célèbre maestro Giuseppe Haydn. Milan.

Casa, Giovanni della. 1558. Il Galateo. Nicolò Bevilacqua.

Cone, Edward T. 1974. The Composer’s Voice. University of California Press.

Eisen, Cliff. 2003. “Mozart’s Chamber Music.” In The Cambridge Companion to Mozart, ed. Simon P. Keefe, 105–17. Cambridge University Press.

Finscher, Ludwig. 1974. Studien zur Geschichte des Streichquartetts. Bärenreiter.

Framery, Nicolas Etienne, Pierre Louis Ginguené, and Jérôme-Joseph de Momigny, eds. 1818. Encyclopédie méthodique: Musique. Vol. 2. Chez Panckoucke.

Grétry, André. 1789. Mémoires, ou essai sur la musique. Volume 1. Chez l’auteur.

Hepokoski, James and Warren Darcy. 2006. Elements of Sonata Theory: Norms, Types, and Deformations in the Late-Eighteenth Century Sonata. Oxford University Press.

Keefe, Simon P. 2001. Mozart’s Piano Concertos: Dramatic Dialogue in the Age of Enlightenment. Boydell Press.

Klorman, Edward. 2016. Mozart’s Music of Friends: Social Interplay in the Chamber Works. Cambridge University Press.

Koch, Heinrich Christoph. 1793. Versuch einer Anleitung zur Composition. Vol. 3. Böhme.

—————. (1793) 1983. Introductory Essay on Composition: The Mechanical Rules of Melody, Sections 3 and 4. Translated and with an introduction by Nancy Kovaleff Baker. Yale University Press.

—————. 1802. Musikalisches Lexikon. August Hermann der Jüngere.

Kollmann, Augustus Frederic Christopher. 1799. Essay on Practical Musical Composition, According to the Nature of that Science and the Principles of the Greatest Musical Authors. [Printed for the author.]

Levy, Janet M. 1971. “The Quatuor Concertant in Paris in the Latter Half of the Eighteenth Century.” Ph.D. diss., Stanford University.

Momigny, Jérôme-Joseph de. 1806. Cours complet d’harmonie et de composition. 3 vols. Chez l’auteur.

—————. (1806) 1998. Excerpt from A Complete Course on Harmony and Composition. In Strunk’s Source Readings in Music History, translated and ed. Wye Jamison Allanbrook, 826–48. Revised edition. W. W. Norton.

Monahan, Seth. 2013. “Action and Agency Revisited.” Journal of Music Theory 57 (2): 321–71.

Morabito, Fabio. 2015. “Authorship, Performance, and Musical Identity in Restoration Paris.” Ph.D. diss., King’s College, University of London.

November, Nancy. 2004. “Theater Piece and Cabinetstück: Nineteenth-Century Visual Ideologies of the String Quartet.” Music in Art 29 (1–2): 134–50.

O’Hara, William. 2017. “Momigny’s Mozart: Language, Metaphor, and Form in an Early Analysis of the String Quartet in D Minor, K. 421.” Newsletter of the Mozart Society of America 21 (1): 5–10.

Palm, Albert. 1962–63. “Mozarts Streichquartett D-moll, KV 241, in der Interpretation Momignys.” Mozart-Jahrbuch: 256–79.

Proctor, Gregory Michael. 1978. “Technical Bases of Nineteenth-Century Chromatic Tonality: A Study in Chromaticism.” Ph.D. diss., Princeton University.

Quantz, Joseph Joachim. 1752. Versuch einer Anweisung die Flöte traversiere zu spielen. Johann Friedrich Voß.

—————. 1985. On Playing the Flute. Translated with notes and an introduction by Edward R. Reilly. Faber and Faber.

Rosen, Charles. 1997. The Classical Style: Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven. Expanded edition. W. W. Norton.

Rousseau, Jean-Jacques. 1768. Dictionnaire de musique. Chez la veuve Duchesne.

Schenker, Heinrich. 1954. Harmony. Translated by Elisabeth Mann Borgese. Edited by Oswald Jonas. University of Chicago Press.

Staël, Anne-Louise-Germaine de. 1813. “L’esprit de conversation.” In De l’Allemagne. Vol. 1. H. Nicolle.

—————. 1861. Germany. Translated by O. W. Wight. Vol. 1. H. W. Derby.

Stendhal [Marie-Henri Beyle]. 1814. Lettres écrites de Vienne en Autriche, sur le célèbre compositeur Jh. Haydn. Didot l'aîné.

Sulzer, Johann Georg. 1771–74. Allgemeine Theorie der schönen Künste. 2 vols. Weidmanns Erben und Reich.

Sulzer, Johann Georg and Heinrich Christoph Koch. 1996. Aesthetics and the Art of Musical Composition: Selected Writings of Johann Georg Sulzer and Heinrich Christoph Koch. Translated and edited by Nancy Baker and Thomas Christensen. Cambridge University Press.

Vayer, François la Mothe. 1644. Opuscules, ou petits traictez. Chez Antoine de Sommaville & Augustin Courbé.

Webster, James. 1974. “Towards a History of Viennese Chamber Music in the Early Classical Period.” Journal of the American Musicological Society 27: 212–47.

—————. 1976. “Violoncello and Double Bass in the Chamber Music of Haydn and his Viennese Contemporaries, 1750–1780.” Journal of the American Musicological Society 29 (3): 413–38.

—————. 1977. “The Bass Part in Haydn’s Early String Quartets.” Musical Quarterly 63 (3): 390–424.

Will, Richard. 1997. “When God Met the Sinner, and Other Dramatic Confrontations.” Music and Letters 78 (2): 176–209.

Footnotes

* This study is expanded based on chapters 2 and 4 of my book Mozart’s Music of Friends: Social Interplay in the Chamber Works (2016). Material is adapted with permission from the publisher. This paper was presented in 2016 to the Music Theory Colloquium at the Eastman School of Music and as part of an SMT special session on agency in eighteenth-century music, with co-panelists Robert Hatten, Mary Hunter, and W. Dean Sutcliffe. I am grateful to participants at both events, as well as to MTO’s anonymous peer reviewers, for many helpful comments and suggestions.

Thanks are due to the many musicians who granted permission to use their recordings for audio examples: Example 1 (Mozart K. 498): Bella Hristova, violin; Edward Klorman, viola; Jacqueline Choi, cello; and Gloria Chien, piano. Example 2 (Mozart K. 387): Siwoo Kim, violin 1, Emily Daggett Smith, violin 2; Edward Klorman, viola; and Alice Yoo, cello. Example 3 (Haydn): Gergana Haralampieva, violin 1; Geneva Lewis, violin 2; Zhanbo Zheng, viola; and Audrey Chen, cello.

Return to text

Thanks are due to the many musicians who granted permission to use their recordings for audio examples: Example 1 (Mozart K. 498): Bella Hristova, violin; Edward Klorman, viola; Jacqueline Choi, cello; and Gloria Chien, piano. Example 2 (Mozart K. 387): Siwoo Kim, violin 1, Emily Daggett Smith, violin 2; Edward Klorman, viola; and Alice Yoo, cello. Example 3 (Haydn): Gergana Haralampieva, violin 1; Geneva Lewis, violin 2; Zhanbo Zheng, viola; and Audrey Chen, cello.

1. Unless otherwise indicated, all quotations are provided in my translations. Where published English translations are also available, I have provided citations to facilitate cross-referencing.

Return to text

2. Monahan 2013 (323 n. 3) rightly notes that this bias toward monological personification reflects the emotive aesthetic of the Romantic (and post-Romantic) repertoire discussed in Cone 1974.

Return to text

3. On this point, I am indebted to Charles Rosen, who in an influential analysis of Haydn’s String Quartet in B minor, op. 33, no. 1, remarks on an accompanimental figure that transforms into a principal voice, an event he regards as heralding “a revolution in style” (Rosen 1997, 116–17).

Return to text

4. The term “Kammermusik” retained an older, broader meaning, referring to any instrumental music for the aristocratic chamber, as opposed to church or theater. This category included concerti and symphonies just as well as sonatas. See, for example, Johann Philipp Kirnberger’s entry “Cammermusik” in Sulzer 1771–74; and Koch’s entry for “Kammermusik” in Koch 1802. The changing meaning of the term “chamber music” is also discussed in Eisen 2003.

Return to text

5. On the multiple authorship of Sulzer’s Allgemeine Theorie (1771–74), see Sulzer and Koch 1996, 14, n. 22.

Return to text

6. The original passage appears in Sulzer 1771–74, s.v. “Sonate,” 2:1094–95. Schulz is by no means the first author to discuss a composition’s individual parts as portraying characters engaged in conversation. For earlier sources, see Finscher 1974, 285ff. Definitions of “dialogue” from several eighteenth-century music dictionaries are quoted in Keefe 2001, 26–27.

Return to text

7. For a discussion of H. 579 and other depictions of “confrontational” musical conversations, see Will 1997. Another example of a musical exchange between two explicit characters is Haydn’s divertimento for four-hand keyboard duet known as “Il maestro e lo scolare,” Hob. XVIIa:1, in which the two players represent a teacher and his student. I thank Tom Beghin for bringing this piece to my attention.

Return to text

8. This aspect of Schulz’s commentary was rather old-fashioned by the 1770s and reflects a view of the cello’s role in ensemble music as essentially basso continuo (and thus non-Hauptstimme). Compare this view to Johann Joachim Quantz’s (1752) definition of “quatuor” as a sonata with three concertante instruments and a bass. (N.b.: Quantz refers not to string quartets but to pieces such as Telemann’s Six Quartets for treble winds with continuo). Quantz’s discussion emphasizes that the basso continuo part is different in kind from the more melodic (concertante) upper voices. Among his requirements for “a good quartet,” he lists “a fundamental part with a true bass quality [baßmäßige Grundstimme].” Quantz also requires that “each part, after it has rested, must re-enter not as a middle part [Mittelstimme], but as a principal part [Hauptstimme], with a pleasing melody; but this applies only to the three concertante parts, not to the bass” (emphasis added). Quantz’s only nod to a melodic role for the basso continuo part is a requirement that “if a fugue appears, it must be carried out by all four parts in a masterful yet tasteful fashion, in accordance with all the rules” (302, emphasis added). English translation from Quantz 1985, 316–17. See also discussion in Levy 1971, 46–7.

Return to text

9. An early version of Koch’s “Sonate” discussion appears in Koch 1793, 315–16. See also the English translation published in Sulzer and Koch 1996, 103–5.

Return to text

10. See James Webster’s (1974, 1976, 1977) series of studies examining the evolving role of the cello/bass part in Haydn’s music.

Return to text

11. See also the English translation published in Koch 1983 [1793] 1983, 207. Koch may be responding to Jean-Jacques Rousseau, who defined “quatuor” as follows: “This is the name given to pieces of vocal or instrumental music that are executed by four parts (see Parts). There are no true Quartets, or [if there are] they are worthless. It is necessary in a good Quartet that the parts are nearly always alternating, because in each chord there are at most two parts that are melodic [fassent Chant] and that the ear can distinguish at the same time; the other two are nothing but filler [remplissage], and one must never put filler in a [true] quartet” (Rousseau 1768, s.v. “quatuor”). See original text, Appendix Document #7.

Return to text

12. This perspective anticipates Rosen’s (1997, 116–17) influential commentary about the opening of Haydn’s op. 33.

Return to text

13. Kollmann 1799, which owes a great debt to Koch’s writings, adopts “concerting” as an English equivalent for the German “concertirend.”

Return to text

14. Janet Levy’s (1971, 45–59) critical survey of “concertirend” and “concertant” in eighteenth-century writings meticulously documents four primary meanings: (1) a setting with one player per part; (2) a style resembling dialogue, in which all parts are alternately or mutually important; (3) a soloistic, sometimes virtuosic style; and (4) an opposition, struggle, or competition of unequal forces, from the root “concertare.” Her survey corrects the tendency of modern scholars to interpret the term as necessarily denoting virtuoso display, as in a concerto.

Return to text

15. The article “Trio” in Sulzer 1771–74 was probably written by Schulz.

Return to text

16. The tension between cooperation and competition is a prominent thread in Peter Burke’s (1993, 89–122) discussion of early-modern conversation manuals.

Return to text

17. On m. 39 as a half cadence (as opposed to m. 51), see William E. Caplin’s distinction between “stop” and “end” (Caplin 2004, 97–103 and passim). In the parlance of Warren Darcy and James Hepokoski’s (2006) Sonata Theory, m. 39 commences the “dominant lock,” which obtains until the medial caesura in m. 51.

Return to text

18. I am grateful to Fabio Morabito for his insights regarding the translation of this passage. Carpani’s discussion has subsequently become known in a plagiarized and lightly adapted French-language version by Stendhal (1814).

Return to text

19. Carpani’s gendered characterizations of the instruments’ discourse is striking. The violins and cello are described with words borrowed from rhetoric or regular speech (e.g., parlatore, oratore, interlocutori), whereas the viola character is described as chattering (cicalate, literally, denotes the sound of a cicada) and as pushing her way (intromettersi) into a predominantly male exchange, to which she offers nothing of substance. Carpani’s treatment of the viola as female is puzzling since, at the time, bowed string instruments were played almost exclusively by men. Carpani’s choice is most likely explained by the grammatical gender of the words “il violino,” “il violoncello,” and “la viola” in his native Italian.

Return to text

20. Regarding the hierarchical arrangement within the quartet, see also the unpublished poem “Caractère des divers instrumens” by the famed Parisian violinist Pierre Baillot (1839), which betrays a strong influence of Carpani (through Stendhal). Baillot paradoxically imagines a quartet as a “republic” among friends devoted to music making, yet he regards the violin as the “king,” “father of his subjects” who “commands” while wielding a “scepter” (i.e., his bow). For somewhat divergent readings of the Baillot, Carpani, and Stendhal documents, see Morabito 2015, 86–87 and 233; and Klorman 2016, 41–52.

Return to text

21. The bass line

Return to text

22. Notwithstanding the passage’s clear G-major context, the

Return to text

23. Momigny’s arrangement has been discussed extensively in the literature on the history of analysis. One recent discussion, which includes some useful literature review, is O’Hara 2017.

Return to text

24. Momigny adopts a reduced, six-stave format beginning in the development section.

Return to text

25. The original passage appears in Momigny 1806, 1:371. Another inspiration for Momigny’s arrangement qua analysis may be the influence of his fellow Liègois composer André Grétry (1789, 414), who not long before had posed the question: “Why shouldn’t [instrumental] music be supplied with words, just as one has long set words to music?” The two composers were in close contact in 1803, the same year that Momigny commenced the serial publication of his Cours complet (for details, see Klorman 2016, 53–56).

Return to text

26. On this point, I part company with Albert Palm (1962–1963), whose (otherwise excellent) discussion misrepresents Momigny’s analysis as a dialogue between Dido and Aeneas. Aeneas’s “speaking” role is, in fact, extremely circumscribed, comprising just the two statements shown in Example 5a (“que je suis malheureux” and “fatal devoir”). Ian Bent (1994, 128) describes Momigny’s arrangement as a “monologue of Dido addressing her departing lover Aeneas,” but he does not mention Aeneas’s small speaking role. Although the cello (as Aeneas) is the only “official” pertichino shown in Momigny’s score, his prose commentary implies additional pertichini, as I will discuss below.

Return to text

27. The plural term “les accompagnemens” refers not to “the accompaniment” as a corporate entity but to the individual parts that comprise the accompaniment (in this case the violin, viola, and cello). This usage is similar to the common, eighteenth-century designation for a trio for piano and strings as a “sonate pour le piano avec accompagnemens d’un violon et d’un violoncelle.” See also A. F. C. Kollmann’s (1799, 12) discussion of “sonatas for one or more principal instruments, with some others as accompaniments.”

Return to text

28. In this context, the word “chant” refers not only to the act of singing but specifically to the melodic voice (as in the chant donné in species counterpoint). Momigny’s plate (see again, Example 4a) labels the vocal part (which is identical to the first violin part) as “chant.”

Return to text

29. I am grateful to Nicolas Meeùs for his insights regarding the translation of this passage.

Return to text

30. Note, however, that Cone (1974, 99) specifically points out that the concept of “agent” should not be limited to melodic parts. Incidentally, Momigny’s footnote notwithstanding, his use of “acteur” in this quasi-theatrical context anticipates his future comments in the Encyclopédie méthodique: Musique. He praises the violinist Alexandre-Jean Boucher as an “acteur parfait” (Framery, Ginguené, and Momigny 1818, s.v. “Quatuor,” 2:299) and Pierre Baillot as an “acteur consommé sur le violon” (Framery, Ginguené, and de Momigny 1896, s.v. “Soirées ou Séances Musicales,” 2:374). On a French tradition evoking metaphors of theater for violin performance, see November 2004 and Morabito 2015.

Return to text

31. These sorts of suspension chains most naturally occur between two parts of the same category (cf. the opening of Pergolesi’s Stabat mater, which presents suspension chains first between the two violin sections and subsequently between the two voices). Less idiomatic is the suggestion, implicit in Momigny’s score, that one voice is the human character Dido and the other a non-human, instrumental part.

Return to text

32. This texted rest is needed to complete the word “amour” due to the musical and textual parallelisms between mm. 50–51 and 52–53. Momigny resorts to the same strategy on the downbeat of m. 66, where the final syllable of the word “bonheur” is set to the first violin’s rest.

Return to text

33. The original passage appears in Momigny 1806, 2:392.

Return to text

34. See Chris Ware’s illustration “All Together Now,” which appeared as the cover artwork for the New Yorker magazine’s January 6, 2014 issue. <https://www.newyorker.com/culture/culture-desk/cover-story-all-together-now

Return to text

35. The original passage appears in Staël 1813, 96–97.

Return to text

Copyright Statement

Copyright © 2018 by the Society for Music Theory. All rights reserved.

[1] Copyrights for individual items published in Music Theory Online (MTO) are held by their authors. Items appearing in MTO may be saved and stored in electronic or paper form, and may be shared among individuals for purposes of scholarly research or discussion, but may not be republished in any form, electronic or print, without prior, written permission from the author(s), and advance notification of the editors of MTO.

[2] Any redistributed form of items published in MTO must include the following information in a form appropriate to the medium in which the items are to appear:

This item appeared in Music Theory Online in [VOLUME #, ISSUE #] on [DAY/MONTH/YEAR]. It was authored by [FULL NAME, EMAIL ADDRESS], with whose written permission it is reprinted here.

[3] Libraries may archive issues of MTO in electronic or paper form for public access so long as each issue is stored in its entirety, and no access fee is charged. Exceptions to these requirements must be approved in writing by the editors of MTO, who will act in accordance with the decisions of the Society for Music Theory.

This document and all portions thereof are protected by U.S. and international copyright laws. Material contained herein may be copied and/or distributed for research purposes only.

Prepared by Brent Yorgason, Managing Editor

Number of visits:

10524