Analyzing Schoenberg’s War Compositions as Satire and Sincerity: A Comparative Analysis of Ode to Napoleon Buonaparte and A Survivor from Warsaw

Joon Park

KEYWORDS: Schoenberg, A Survivor from Warsaw, Ode to Napoleon Buonaparte, partition, humor, musical idea

ABSTRACT: This paper presents a comparative analysis of Ode to Napoleon Buonaparte op. 41 (1942) and A Survivor from Warsaw op. 46 (1947) to show that Schoenberg’s compositional decisions for each piece reflect the public’s (and his) change of attitude regarding the historical events surrounding World War II. In particular, I argue that Ode frequently features humorous depiction of the Nazi regime through various types of musical satire whereas Survivor’s overall compositional planning and execution are more in line with his other compositions without a satirical tone, for example, the String Trio op. 45. The analyses in this paper show humorous elements in Schoenberg’s Ode to Napoleon and demonstrate how these elements are avoided in Survivor from Warsaw to make space for the sincere criticism of the Nazi party and to raise awareness for the survivors. I begin by interpreting satirical passages in Ode as instances of incongruent juxtapositions and then examine the different ways the incongruence manifests. I then discuss the leitmotivic partitioning of various twelve-tone row forms in Survivor to show the compositional congruence between the text, musical textures, and partitioning schemes. Given the change of compositional mood between Ode and Survivor (in addition to the historical evidence), this paper speculates that Schoenberg’s motivation for composing Survivor was to rectify the narrative tone he adopted in Ode.

DOI: 10.30535/mto.26.4.5

Copyright © 2020 Society for Music Theory

Introduction

[0.1] Charlie Chaplin’s 1940 movie The Great Dictator presents an interesting case for satire’s adequacy (and inadequacy) in regard to the severity of its object of attack. At the time of production and release, the movie was praised for its comedic depiction of the dictator, and it garnered a large audience.(1) However, Chaplin later wrote, “had I known of the actual horrors of the German concentration camps, I could not have made The Great Dictator; I could not have made fun of the homicidal insanity of the Nazis” (1964, 426). Chaplin’s remark sheds light on the shift in the American public’s view of the war after it was revealed to them how much the victims of the Holocaust suffered. Prior to knowing of the massacre, satire was an acceptable, even celebrated, form of public criticism.(2) Once survivors began to testify about the Holocaust, however, knowledge of the severity of their struggle made satire no longer a suitable form of protest. Realizing afterward that his satire did nothing to help the victims, Chaplin expressed concern about making the movie because it revealed the naïveté of the false optimism that he once had.

Example 1. Chaplin with Schoenberg (Copyright © Roy Export Company Ltd.). Used with permission

(click to enlarge)

[0.2] While Chaplin was filming The Great Dictator, Arnold Schoenberg was composing Ode to Napoleon Buonaparte, op. 41 (1942). The two creators were in the same social circle in southern California, and Schoenberg’s Ode to Napoleon seems to share a similar mode of criticism to Chaplin’s The Great Dictator, namely, a satiric depiction of the Führer. Both adopt mock elevation as a method of satire by using the word “great” or “ode” in the title of their works. Schoenberg, who admired Chaplin’s work,(3) even visited the set of The Great Dictator during filming (Example 1).(4) Since both artists were working on projects that criticized Nazi Germany, it is understandable that the two adopted a similar mode of critique. Did Schoenberg express a similar post-war regret after learning of the severity of the violence during the war?

[0.3] This paper presents a comparative analysis of Schoenberg’s two war compositions Ode to Napoleon Buonaparte, op. 41 (1942), and A Survivor from Warsaw, op. 46 (1947), showing how the compositional decisions for each piece reflect the public’s (and his) change of attitude regarding historical events. In particular, I argue that Ode frequently features a humorous depiction of the Nazi regime through various types of incongruous juxtapositions for comedic effect.(5) In contrast, Survivor’s compositional planning and execution contribute to the overall sense of musical coherence and are more in line with Schoenberg’s other compositions, which do not adopt a satirical tone.(6) The difference in mood between the two pieces can be understood in light of the change in public perception about the war. As the news that the Nazis were massacring the Jewish people spread, the war’s cruelty was made clearer to those in the United States. Satire and mockery of the Nazi party during the war’s early stages were quickly replaced by support and solidarity for the victims, which continued after the war’s end in 1945.

[0.4] While Schoenberg was composing Ode in 1941 and 1942, the extent to which the Jewish people suffered under Nazi Germany was not widely known in the United States, because the news from the concentration camps was not available to the outside world. It was around mid-1942 that newspapers began to report the Nazi encampments’ brutal conditions.(7) Without much information about the suffering, the dictator’s rise to power may have found fertile ground for political satire in the public sphere across the Atlantic Ocean.

[0.5] In addition to the analytical evidence for my interpretation of Ode, there is also circumstantial evidence for interpreting Ode as a satire. For example, Schoenberg’s program note belittles the Nazi party by comparing it to a hive of bees and Hitler to a queen bee: “the Queen or the Führer

[0.6] Schoenberg’s later composition A Survivor from Warsaw, op. 46 (1947), shares in common with Ode a focus on the events surrounding the Second World War. The mood of the composition, however, differs greatly. Rather than setting a pre-existing poem to music, the composer wrote the text of A Survivor from Warsaw himself, narrating the brutal violence of the Warsaw Ghetto in 1943. Its use of three languages—English for the narrator, German for the soldiers, and Hebrew for the prayer—adds to the sense of reality during listening. In contrast to Ode’s poetic depiction, Survivor presents cinematic flashbacks with the different languages and diegetic accompaniment. As a result, Survivor sounds far more immediate than Ode. The music for Survivor resembles a cinematic score, providing a vivid sonic depiction of the events. In other words, Ode sounds more like a comedic recitation while Survivor sounds like a documentary with religious overtones.

[0.7] My interpretation of the relationship between Ode and Survivor echoes a recurring cultural trope about satire’s ineffectiveness in generating robust social change. A work of satire may create a false optimism when the situation, in fact, requires a sincere engagement with the problem that often demands more time and effort. The satirist and novelist Jonathan Coe goes further by saying that “[L]aughter is not just ineffectual as a form of protest

[0.8] This article unfolds in three sections. The first section discusses the multiple meanings of tonal elements in Ode by referencing a similar compositional strategy that Schoenberg adopted in his earlier work, Three Satires, op. 28 (1926). Just as some tonal elements in Three Satires can be interpreted as sardonic and others as genuine, some tonal elements in Ode can be read as satiric depictions of the brutal regime and others as sincere support for the Allied forces. This interpretation contrasts with earlier analyses of Ode that consider all tonal elements as signifying a singular idea, a supposed “return to tonality” (Keller 1981; MacDonald 2008). I argue that each tonal moment in Ode can be interpreted differently, depending on its dodecaphonic and textural contexts. The second section focuses on the role of incongruent juxtaposition in generating a satirical effect. The satirical passages in Ode will be interpreted as instances of “valence shifts,” a term used in linguistic theories to describe verbal humor and adopted by James Palmer (2017) in his analyses of eighteenth-century Viennese classical composers’ music. The sudden interjections of tonal elements within the overall dodecaphonic texture function as valence shifts that signify musical humor in Ode. In addition to present-day music theoretical work, I will relate the exaggerated juxtaposition of opposing styles to the literary satires of Karl Kraus, whom Schoenberg admired greatly. The third section investigates the harmonic organizations of Ode and Survivor to show that Schoenberg’s treatment of the row forms differs between the two compositions. Based on Schoenberg’s pre-compositional sketches, I present an intentional distortion of row forms in Ode and show how this type of distortion is avoided in Survivor to make way for a leitmotivic partitioning. This shows congruence among the text, musical textures, and partitioning schemes in Survivor that contrast with the incongruences of Ode.

Multiple Meanings of Tonal Elements in Three Satires and Ode to Napoleon

Example 2. Schoenberg, Ode to Napoleon Buonaparte, mm. 261–267, final

(click to enlarge)

[1.1] The appearance of major triads in Ode are, perhaps, one of the most unusual features of the composition, considering Schoenberg’s late style.(10) One can hear the contextual difference between his treatments of a major triad without intimately knowing their dodecaphonic context. These tonal moments recall other tonal works to create a broader narrative of a “return to tonality” (Keller 1981; MacDonald 2008).(11) In particular, the piece’s ending chord, an

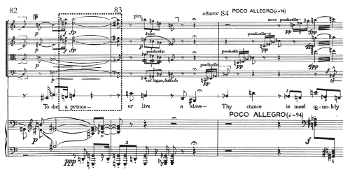

Example 3. Schoenberg, Ode to Napoleon Buonaparte, mm. 82–84 and 144–146, triads (outlined with dotted lines) as fanfare

(click to enlarge)

[1.2] While this perspective is compelling, it explains only this one particular chord. Other instances of tonal elements—for example, the major triads in m. 82 and its repetition in m. 145 (Example 3)—sound neither heroic nor reminiscent of tonal compositions by Beethoven or other composers. For this reason, I am skeptical about treating all tonal artifacts in Ode as expressing some singular idea.(14) The different meanings of tonal elements should be problematized with attention to their particularity. Each tonal chord might mean something different based on its musical context. Some chords might have been used sincerely and others sarcastically. In this regard, the major triads used in mm. 82 and 145 echo the earlier treatment of tonal elements in Schoenberg’s Three Satires, op. 28.

[1.3] Both Three Satires and Ode employ tonal elements within a twelve-tone context, and both are composed in a spirit of protest. Just as Ode protests the Nazi regime, Three Satires criticizes the young composers who clung to the last vestiges of what Schoenberg considered an “outmoded style” (Auner 2003, 176). Schoenberg wrote a foreword to clarify whom his satires were directed against: they are for “all those who seek their personal salvation by taking the middle road” (186). In addition to clarifying the object of attack, the foreword’s last paragraph helps us understand Schoenberg’s rhetorical view. Satire is less about making fun of the opponent and more about effectively delivering a pointed critique:

I cannot judge whether it is nice of me (it will surely be no nicer than anything else by me) to make fun of certain things that were intended to be serious, show considerable talent, and are in part worthy of respect, knowing as I do that anything can be made fun of. About much sadder things. And in a much funnier way! In any case, I am excused since as usual I have done it only as well as I am able. May others be able to laugh about it more than I can; more than I, who am also able to take it seriously! (Auner 2003, 187)

For Schoenberg, satirizing did not mean that he was taking the subject lightly. Rather, satire served as a tool to bring out internal contradictions in the opponent’s logic.(15)

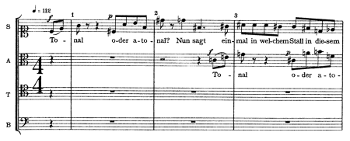

Example 4. Schoenberg, “Am Scheideweg” (At the Crossroad) from Three Satires, mm. 1–3

(click to enlarge)

[1.4] Each of the Three Satires can be heard as a composing-out of the internal contractions of the middle-of-the-road approach.(16) Among the three, the first movement, “Am Scheideweg” (At the Crossroads), uses a palindromic row-form presentation that begins and ends with an arpeggiation of a C-major triad. The opening arpeggiation is accompanied by the word “tonal” (Example 4). Due to the movement’s design as a canon in four parts, the word “tonal” and the C-major triad repeat throughout the piece. The meaning of this exaggerated repetition seems clear––to highlight the nauseating repetition of the tonal style, which does not inspire the emergence of a new musical idea. In contrast to the triad, the third movement’s opening C major scale fragment (C–B–A–G), another tonal element, seems to demonstrate how a tonal element can be properly incorporated within the context of a dodecaphonic texture.(17) Schoenberg’s use of tonal elements in Three Satires exemplifies that within the span of a single work, different tonal elements can be used to signify different rhetorical gestures: one as a sardonic criticism and the other as a sincere gesture of compositional demonstration. The tonal elements in Ode seem to portray these two contrasting modes in a similar manner.

[1.5] Measures 82–84 of Ode feature a fanfare-like gesture in the strings (see again Example 3).(18) Combined with the text, “a prince,” this moment can be heard as portraying a triumphant image of royalty, yet it seems to suggest the opposite. The B-major triad and its rhythm, a sixteenth note followed by a half note, sound too stereotypical of a fanfare. The fanfare in m. 82 is accompanied by a drastic change of dynamics that move from piano to forte and back to fortepiano in a single measure. For a brief moment, all of the complexity of twelve-tone music is halted and the cliché sound mocks the faded glory of a fallen prince, recalling such satirical devices as mock encomium and travesty. The extended techniques used in the next measure (pizzicato, sul ponticello, and col legno battuto) diminish the resonance of arco playing as if to depict the prince losing his voice. In the meantime, the left-hand gesture mimics the dominant-to-tonic movement in a march-like rhythm, which emphasizes the note G. Again, it could have been a triumphant gesture if the dynamics were louder than pianississimo. Rather than the confident stomping of a prince, it sounds like the timid steps of a person who walked confidently in the past. In a meaningful way, the major triad and the gestures surrounding it resemble the major triad in the first movement of Satires. They are both signifiers of a bygone era, used in order to highlight their inadequacy.

[1.6] The final

Incongruent Juxtaposition as a Humorous Effect

[2.1] The way Schoenberg uses the major triad as an element of satire is emblematic of other satirical moments in Ode. The juxtaposition of the twelve-tone texture and easily recognizable (and often tonal) musical gestures recalls Poundie Burstein’s “humor equation,” which consists of two necessary elements: “things that are somehow serious, sensible, logical, or ‘lofty,’” on the one hand, and “things that are trivial, silly, illogical, or base,” on the other (1999, 69). As James Palmer notes, juxtaposing two opposing elements “creates the impression of a sudden and immediate pull in an unexpected direction” (2017, [3.2]). More specifically, he proposes that the interaction between musical syntax and musical topics (as a part of musical semantics) plays a crucial role in the construction of musical humor. Palmer uses the traditional tonal syntax of the classical style as a main driver of musical syntax in his analyses. In my analysis of Ode, I treat syntax more loosely: as a default mode of one’s expectation when listening to a twelve-tone composition. After almost two minutes of hearing a twelve-tone texture in the introduction, a listener would expect a similar texture to continue. This expectation is what I consider the main driver of musical syntax in Ode. Although Palmer’s investigation focuses on the first Viennese school, his structure of musical humor is applicable to the second Viennese school as well.

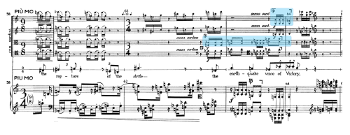

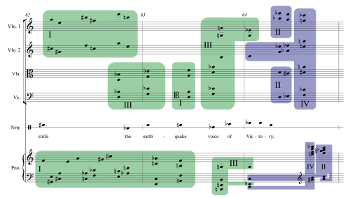

Example 5. Schoenberg, Ode, mm. 58–64, Marseillaise and Beethoven quotations

(click to enlarge and see the rest)

[2.2] In mm. 62–64 of Ode, the witty collage of the Marseillaise theme and the much-noted quotation of Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony can be interpreted through a humor-informed lens. As one of the earliest appearances of tonal elements in Ode, this moment presents a sudden break from the twelve-tone texture for the first time (Example 5).(19) Modern, twentieth-century concert music is suddenly turned into an eighteenth-century street anthem, which is then followed by a contemporary TV broadcast campaign (as described in endnote 12). All of these familiar sounds suddenly disappear, and the modern twelve-tone texture comes back again in the following passage. For those who noticed all of the quotations (i.e., the Marseillaise theme, Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony, and the letter V in Morse code), this passage might sound like what one would hear when flipping through radio frequencies. The accompanying text “the earthquake voice of victory” refers to the voice of a dictator, according to the poetic context. And the juxtaposition of the text with this collage is, again, sarcastic because it trivializes the propaganda’s serious message as a mere radio frequency. No matter how loud the tyrannical government chants their victory, their message loses the listener’s attention and the listener quickly attends to the more interesting sound. This gesture undermines the effectiveness of the oppressing force.

[2.3] Schoenberg’s use of incongruous juxtaposition as a way to convey musical satire was influenced by the narrative structure of Karl Kraus’s satire.(20) Julian Johnson (2001) draws connections between Kraus’s and the Schoenberg School’s use of style juxtaposition for ironic purposes:

One of the most intriguing of these parallels [between Kraus’s writings and the Schoenberg School’s musical output] is the shared use of stylistic juxtaposition as a compositional technique. According to Sigurd Scheichl, Kraus used “the juxtaposition of debased dialect with elevated diction.” The effect of this is directly comparable with the ironic use of style juxtaposition in Mahler’s music, which was of course revered by the Schoenberg School. The critical use of ironic juxtaposition. . . was, briefly, a feature of Schoenberg’s [music], once again during the period when Kraus’s influence was most direct, in the works like the Second String Quartet (1908) with its Mahlerian distortion of “Ach, du Liebe Augustin” or the grotesque disfigurement of cabaret songs in Pierrot Lunaire (1912). (2001, 104)

The juxtaposition of tonal elements within the overall twelve-tone texture in Ode suggests that Kraus’s influence was not limited to Schoenberg’s early works, as Johnson suggested, but was felt even in Schoenberg’s later years.

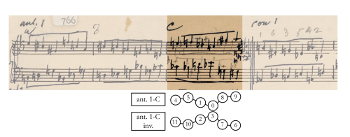

Example 6. Ode, MS 767, four hexachords with roman numerals

(click to enlarge)

[2.4] Revisiting the sarcastic use of a major triad in mm. 82–84 (Example 3), the incongruous juxtaposition coincides with Schoenberg’s choice of hexachords for these triads. When a major triad is expressed within a single hexachord, it is considered congruent, but when it is expressed within two different hexachords, it is considered incongruent. Comparing Schoenberg’s row presentations in the three passages above (mm. 64, 82, and 145) with the final

Example 7. Hexachords in Ode, mm. 62–64

(click to enlarge)

Example 8. Hexachords in Ode, mm. 80–83

(click to enlarge)

[2.5] The tonal triads in mm. 64, 82, and 145, however, all involve two hexachords, all because of a single note that is not a part of the underlying hexachord. In other words, the hexachord’s tonal possibilities are not realized in the tonal triads. Examples 7 and 8 show simplified scores of the excerpts surrounding mm. 64 and 82. What is happening on the downbeat of m. 64 is quite ironic. In m. 63, the violins and piano are playing a G-major triad, which is the dominant of the following C-minor triad. This dominant-to-tonic progression is successfully executed on the surface, perhaps to project a victorious tonal gesture. This seemingly victorious moment, however, lacks the proper presentation of the tonic because hexachord III does not contain the note C. The fanfare in m. 82 suffers a similar deficiency, because one of its crucial chord tones,

Example 9. Hexachords in Ode, mm. 259–267

(click to enlarge)

[2.6] Considering how these earlier passages produced triads, the final

[2.7] Jack Boss’s meta-analytical approach to Schoenberg’s twelve-tone compositions can help situate Ode’s compositional strategy within the broader context of Schoenberg’s other compositions. Boss, with information from Schoenberg’s own writings and other related philosophical literature, observes that Schoenberg often constructs the conceptual framework of an entire composition by setting up a problem, providing various attempts to solve it (all of which eventually fail), and presenting the ideal version at the end. Although the ideal versions often take the form of intervallic or pitch-class symmetry, they are not necessarily limited to symmetrical shapes.(27) In Ode, Schoenberg presents the problem as the failed attempts at constructing a tonal triad within a single hexachord. The words that are associated with the fallen dictator (e.g., “the earthquake voice of victory” and “to die a prince”) correspond with the musical idea’s earlier stages. The final and successful presentation of the

[2.8] This analysis offers us a context for interpreting Schoenberg’s next war composition, A Survivor from Warsaw, op. 46. Not only does the later composition memorialize and honor the victims of the Holocaust, we can also hear it as a response to his earlier satirical depiction of the brutal regime; it shifts the focus away from the (now defeated) oppressor and toward the oppressed. As we shall see, Schoenberg’s compositional method in Survivor can be understood as a way to construct narrative immediacy. Gone is Ode’s ironic distance, a work based on a poem about a historical figure a century prior. Schoenberg’s text and music in Survivor instead present vivid scenes that force the listener to face the brutality in a firsthand account. The musical gestures are directly relatable to the text.(28) In other words, Survivor closes the gap that existed between the “high” and “low” oppositions (and the valence shifts between them) presented in Ode.

The Row Presentation Strategies in Ode to Napoleon and A Survivor from Warsaw

[3.1] The difference in overall mood between Ode and Survivor is easily noticeable even without explicit knowledge of Schoenberg’s compositional methods. Not only are there strong connections between the text and music in Survivor (e.g., in m. 41, the “shrill breaking voice of the [German] sergeant” is accompanied with tremolos in the piccolo, horn, and xylophone), the composition also avoids many musical cues that might be interpreted as lighthearted. For example, the rhythmic and metric profiles of the compositions’ respective introductions underscore notable differences. Ode begins with fast-paced, measured tremolos (perhaps mimicking the sound of a swarm of bees, as suggested by Schoenberg’s program note), while Survivor begins with the unmistakable sound of reveille, continues with a series of long held notes with unmeasured tremolos of varying speed, and generally avoids an overt invocation of meter. Survivor also does not employ any overt tonal references that might create a textural—and for that reason an ironic—gap within the composition’s overall twelve-tone idiom.(29) Finally, the Hebrew prayer at the end eliminates any possible satirical reading of the composition.

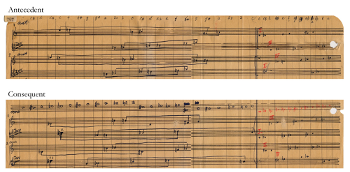

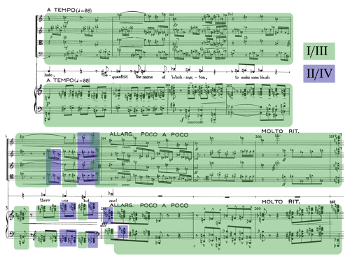

Example 10. Ode, MS 766, I-combinatorial hexachord pairings

(click to enlarge)

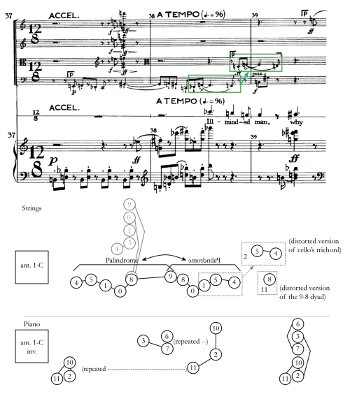

Example 11. Pitch-class map of Schoenberg’s first draft of Ode, mm. 37–39

(click to enlarge)

Example 12. Pitch-class map of the published score of Ode, mm. 37–39

(click to enlarge)

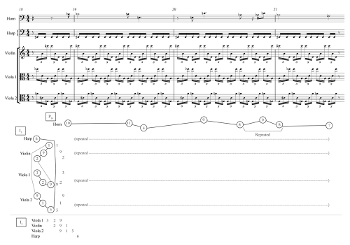

[3.2] The compositional methods for the two works echo the contrasts in their textural characteristics. In Ode, as noted by many scholars, there exists an uncertainty in Schoenberg’s compositional (or pre-compositional) process.(30) In some cases, it seems as though he intentionally dismantled the proper presentation of the row form for text-painting purposes. Example 10 shows Schoenberg’s pre-compositional sketch of the two I-combinatorial hexachords (MS 766), which are used in mm. 37–39. Example 11 shows Schoenberg’s first draft (MS 773) of mm. 37–39 and its “pitch-class map” (in a style similar to Boss 2014), which shows the hexachords employed in this section as well as the pitch classes’ order positions. Example 12 is the published score of the same passage with its pitch-class map.(31) This passage can be largely analyzed with Schoenberg’s hexachords “antecedent 1, version c” (indicated with the box in Example 10). The big roman numeral I written on the first draft (before m. 39) might also suggest that this passage was originally conceived as the composing-out of hexachord I, whose pitch-class collection creates HEX(0, 1), as shown in Example 6. Following the order positions, mm. 37–39 can be recognized as the composing-out of these inversionally combinatorial hexachords. The primary form of the hexachord <4, 5, 1, 0, 8, 9> is used among the strings, where the cello takes the horizontal presentation of the hexachord, followed by its retrograde. This creates a pitch-class palindrome for the cello’s presentation in mm. 37–38. The string chord in the second half of m. 37 uses the same hexachord with some doubled notes. The piano uses the inverted form of the hexachord <11, 10, 2, 3, 7, 6> where the bottom staff is reserved for the first trichord <11, 10, 2> and the top staff for the second trichord <3, 7, 6>.

[3.3] The main discrepancies between the first draft and published score lie in mm. 38–39. Looking at the first draft, it seems that Schoenberg might have originally conceived the viola and cello parts as the literal composing-out of the antecedent 1-C hexachord.(32) This five-note group, however, is distorted in the published version. Instead of maintaining the viola’s

[3.4] The distorted row presentation (displacing a note by a half or whole step) and privileging of tonal sounds over the twelve-tone texture are two compositional aspects absent in Survivor. In Survivor, there seems to be a compositional transparency when it comes to presenting the row forms. Survivor’s organization of row forms is straightforward, and one can confidently identify all the notes with their associated row forms, as Amy Lynn Wlodarski (2007) and Joe Argentino (2013) demonstrate. Schoenberg’s partitioning scheme contributes to the easy recognition of the row forms. The ways the rows are partitioned seem to be motivic, which makes row recognition a fortuitous byproduct.

[3.5] Focusing on the partitioning scheme as a motivic layer, Survivor’s sudden change in partitioning scheme between the narration section (mm. 1–80) and prayer section (mm. 80–99) can be understood as a significant marker for Schoenberg’s motivic partitioning of the row.(34) The partitioning scheme that opens the prayer section (in conjunction with the complete horizontal presentation of the aggregate) can be interpreted as projecting the “ideal shape.” In contrast, the narration section’s partitioning scheme can be interpreted as various attempts to present the ideal shape, which ultimately fail for different reasons. In both cases, the direct connection between the notes and their row-form membership, afforded by the clarity in the row partition, bridges the interpretive gap that was present in Ode. I will first demonstrate how the ideal shape is presented during the prayer section and then show how the partitioning schemes are generally constructed. Finally, I will investigate the failed attempts at projecting the ideal shape during the narration section.

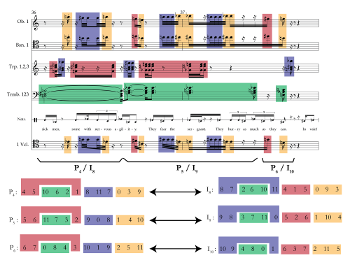

Example 13. Ode, mm. 80–84, orchestra partitioning scheme

(click to enlarge and see the rest)

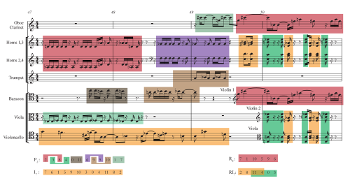

[3.6] The ideal shape encompasses the complete horizontal presentation of the aggregate at the proper transpositional level (P10) through what I call the interlocking trichordal partition of the I-combinatorial hexachords. Example 13 shows the partitioning scheme of mm. 80–84, the beginning of the prayer section.(35) Accompanying the principal tone row’s horizontal presentation in the choir (doubled with trombone 1) is the interlocking trichordal division. Each hexachord of the row is divided into two trichords occupying the order positions 0, 1, 3 and 2, 4, 5. As a result, two pitch-class sets—for example, in the first I-hexachord: {1, 2, 3} and {5, 6, 9}—are highlighted, and these belong to set-classes 3-1 (012) and 3-3 (014), respectively. In addition to the pitch-class sets that are generated from this partition (which are used less frequently during the narration section), I want to bring attention to how the partitioning scheme interlocks over the hexachords. By switching the two middle order positions (2 and 3), this partition resembles two interlocking hands, perhaps symbolizing the solidarity among the survivors of Warsaw. The interlocking partition continues throughout the prayer section.

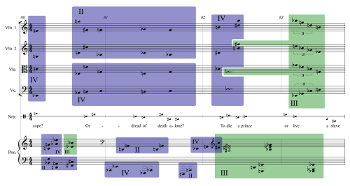

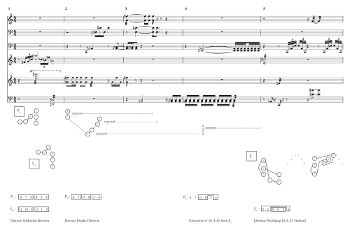

Example 14. Schoenberg, A Survivor from Warsaw, mm. 1–5, pitch-class map and partitioning scheme

(click to enlarge)

[3.7] The opening passage (mm. 1–5) presents three different partitioning schemes, which recur throughout the narration section. Example 14 shows the simplified score at the top, the pitch-class map in the middle, and the partitioning scheme at the bottom. Measure 1 begins by dividing the I-combinatorial hexachords, P6 <6, 7, 0, 8, 3, 4> and I11 <11, 10, 5, 9, 1, 2>, by their discrete trichords, P6’s {6, 7, 0} and {3, 4, 8}, and I11’s {5, 10, 11} and {9, 1, 2}.(36) The following measures (mm. 2–4) present the division of the same hexachords by their discrete dyads, which generates ic1 for the outer dyads and ic4 for the inner one.(37) In m. 4, with the reentry of the dyad {4, 8} and the continued tremolo of dyad {8, 0}, the passage extracts the pc-set {0, 4, 8} from the hexachord P6. Taking the augmented triad as a common trichord, the hexachord changes to I2 in m. 5, where the trichord exists as a collection of contiguous pitch classes. The passage ultimately presents the partitioning scheme that appears throughout the narration section, which successively features the hexachords that contain 3-12 (048) in order positions 2, 3, 4, and 3-4 (015) in order positions 0, 1, and 5.

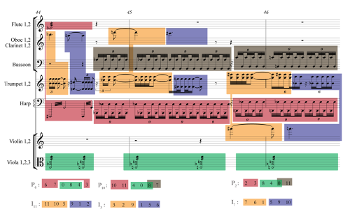

Example 15. A Survivor from Warsaw, mm. 36–37 (sans percussion), combination of the trichordal and 3-12 privileging partition

(click to enlarge)

Example 16. A Survivor from Warsaw, mm. 44–46 (sans narration), combination of the dyadic, trichordal, and 3-12 privileging partition

(click to enlarge)

[3.8] These three schemes—the trichordal, dyadic, and 3-12 privileging partitions—are combined, merged, or altered to generate more complex partitioning schemes throughout the narration section. For example, in mm. 36–37, Schoenberg combines the trichordal and 3-12 privileging partitions back to back (Example 15). This section maintains the partitioning scheme while moving through different row forms. As Argentino (2013, 15) observes, we can interpret this section’s repeating T1 (i.e., the progression from P4/I8 to P5/I9 to P6/I10) as a foreshadowing of the stampede passage’s complete cycle of T1 (mm. 71–80); the connection between the two sections is made clearer, due to the similarity in their partitioning scheme. At other times, all three partitioning schemes operate simultaneously, as seen in mm. 44–46 (Example 16). Measure 44 begins with the trichordal division of I11 (first hexachord) among the oboe, clarinet, and trumpet, and the 3-12 privileging partition of P6 (first hexachord) among the flute, harp, and viola. When the bassoon enters, the partitioning scheme changes to the dyadic division of P10 (first hexachord, two outer dyads) between the bassoon and harp, the 3-12 privileging partition of the same hexachord, and the trichordal division of I3 (first hexachord) among the oboe, clarinet, and trumpet. A similar combination of these three different partitioning schemes continues in mm. 45–46.

Example 17. A Survivor from Warsaw, mm. 18–21, pitch-class map and partitioning scheme of I3

(click to enlarge)

[3.9] Taking the ideal shape as a reference, we can interpret the earlier instances of the aggregate’s full or partial horizontal statement as unsuccessful attempts at projecting the ideal. Measures 18–21 and 47–50 are two notable instances of the horizontal aggregate statement. The first attempt in mm. 18–21 contains the melody of the prayer at its ideal transpositional level (P9), but the accompanying strings and harp do not project the interlocking trichordal division, and none of the set classes projected by the interlocking partition are presented. Example 17 shows the simplified score of this passage with the pitch-class map and the partitioning scheme. The strings repeat three different trichords, each constructed by taking three pitch classes that begin from order positions 0, 1, and 2 (violin 1’s trichord consists of the pitch classes from order positions 1–3, the upper viola from order positions 0–2, and the lower viola from order positions 2–4). This leaves the pitch class that occupies order position 5, which is played by the harp. This horizontal row presentation is cut short after the first hexachord, as if to depict “the forgotten creed.”

Example 18. A Survivor from Warsaw, mm. 47–50, partitioning scheme

(click to enlarge)

[3.10] The second attempt at horizontal presentation in mm. 47–50 presents a partitioning scheme that is similar to the ideal shape, but ultimately fails because it is missing the interlocking trichordal division. Instead, this section features an interlocking dyadic partitioning of P2 between order positions 0, 2 and 1, 3, with the remaining dyad occupying order positions 4 and 5. Example 18 shows the simplified version of the passage with the partitioning scheme. The overall texture of this section is similar to the preceding section (mm. 44–46, Example 16) but the viola’s oscillation between

[3.11] Looking at Survivor’s partitioning scheme within the broader context of the textural shift (i.e., from narration to hymn) and the changes of language (English, German, Hebrew), I sense a narrative congruence throughout the composition in which different aspects create a single story of a survivor recalling his Jewish heritage despite the Nazi regime’s brutal attempt to annihilate Judaism. In contrast to the valence shifts in Ode, which generated comedic effects, the textural shifts in Survivor emerge as a process of realizing the row’s ideal presentation, which in turn signals the realization of Jewish identity. The coherence among the musical attributes (e.g., text-painting, pre-compositional planning, and partitioning schemes), combined with vivid depictions of violence, foregrounds the music’s immediacy. This congruence of perception and narrative closes the gap that was opened by Schoenberg’s satirical depiction of the dictator. In other words, whereas Ode facilitates a gap between listeners and the then-despotic regime, Survivor removes the sense of ironic distance between listeners and the Holocaust. Given the change of compositional mood between Ode and Survivor (in addition to the historical evidence), I speculate that Schoenberg’s motivation for composing Survivor was to rectify the narrative tone he adopted in Ode.

Conclusion

[4.1] Setting Schoenberg’s motivations aside, the analyses I have presented here suggest possible interpretive strategies for these two pieces. This approach is, perhaps, more resonant for today’s listeners, given our current international political climate. As Schoenberg noted of Ode in 1942, history again seems to be “produc[ing] another generation of the same sort.” In our time, the resurgences of fascist ideals, including the Neo-Nazis’ recent rise to newfound political power, force us to examine current events through the lens of the past. This bears a similarity to how Schoenberg initially understood the Second World War through the historical events surrounding Napoleon Buonaparte. This perceived repetition of historical events is echoed in Karl Marx’s famous aphorism: “[A]ll great events and characters of world history occur, so to speak, twice

[4.2] If the tragic events of our current moment––police brutality, racism, the forced separation of migrant children from their parents, mass shootings, the introduction of legislation against women’s rights, and so forth––are mainly consumed by the public sphere as materials for comedy rather than genuine calls to action, then the public will not gain enough momentum to effect a necessary change.(39) By interpreting Ode to Napoleon as a musical satire and A Survivor from Warsaw as a tribute to the victims of the Nazi regime, I would argue that Schoenberg has given us the first as farce and the second as tragedy, a reversal of Marx’s original formula. Following Schoenberg might suggest that coping with today’s tragic events with mere laughter will lead to an even greater tragedy, for which laughter will no longer be appropriate.

Joon Park

University of Arkansas

Department of Music

377 N. McIlroy Ave.

Fayetteville, AR 72701

joonpark@uark.edu

Works Cited

“1,000,000 Jews Slain by Nazis, Report Says: ‘Slaughterhouse’ of Europe Under Hitler Described at London.” 1942. New York Times, June 30, 1942.

Argentino, Joe. 2013. “Tripartite Structures in Schoenberg’s A Survivor from Warsaw.” Music Theory Online 19 (1). https://doi.org/10.30535/mto.19.1.1.

—————. 2019. “Contextual Invariance and Schoenberg’s Hexatonic Webs.” Music Theory Spectrum 41 (1): 104–25. https://doi.org/10.1093/mts/mty026.

Auner, Joseph, ed. 2003. A Schoenberg Reader: Documents of a Life. Yale University Press. https://doi.org/10.12987/yale/9780300095401.001.0001.

Boss, Jack. 2014. Schoenberg’s Twelve-Tone Music: Symmetry and the Musical Idea. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781107110786.

Burstein, L. Poundie. 1999. “Comedy and Structure in Haydn’s Symphonies.” In Schenker Studies 2, ed. Carl Schachter and Hedi Siegel, 67–81. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511470295.007.

Chaplin, Charlie. 1964. My Autobiography. Simon & Schuster.

Cholopov, Yuri. 2002. “Ode to Napoleon Buonaparte: Serial? - or Tropal? - or Modal? - or Newtonal?” In Arnold Schoenberg in America, ed. Christian Meyer, 69–92. Arnold Schönberg Center.

Coe, Jonathan. 2013. “Sinking Giggling into the Sea.” Review of The Wit and Wisdom of Boris Johnson by Harry Mount, London Review of Books 35 (14): 30–31. https://www.lrb.co.uk/the-paper/v35/n14/jonathan-coe/sinking-giggling-into-the-sea.

Crittenden, Camille. 2019. “Ode to Napoleon Buonaparte (Lord Byron) for String Quartet (Orchestra), Piano and Reciter op. 41 (1942/43).” Compositions, Arnold Schönberg Center, English website. Last updated July 8, 2019. https://www.schoenberg.at/index.php/en/joomla-license-sp-1943310036/ode-to-napoleon-op-41-1942.

Crowther Jr., Bosley. 1940. “The Screen in Review; ‘The Great Dictator,’ by and with Charlie Chaplin.” New York Times, October 16, 1940

“Film Money-Makers Selected by Variety: ‘Sergeant York’ Top Picture, Gary Cooper Leading Star.” 1941. New York Times, December 31, 1941.

Föllmi, Beat A. 2002. “Intertextualität und Distanz als Mittel zur politischen Aussage: Arnold Schönbergs ‘Ode to Napoleon Buonaparte.’” In Arnold Schoenberg in America, ed. Christian Meyer, 93–103. Arnold Schönberg Center.

Goehr, Alexander. 1985. “Schoenberg and Karl Kraus: The Idea behind the Music.” Music Analysis 4 (1–2): 59–71. https://doi.org/10.2307/854235.

Johnson, Julian. 2001. “The Reception of Karl Kraus by Schönberg and His School.” In Reading Karl Kraus: Essays on the Reception of Die Fackel, ed. Gilbert J. Carr and Edward Timms, 99–108. Iudicium.

Keller, Hans. 1981. “Schoenberg’s Return to Tonality.” Journal of the Arnold Schoenberg Institute 5 (1): 2–21.

MacDonald, Malcolm. 2008. Schoenberg. 2nd ed. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195172010.001.0001.

Marcuse, Herbert. 1969. “Epilogue to the New German Edition of Marx’s 18th Brumaire of Louis Napoleon.” Translated by Arthur Mitzman. Radical America 3 (4): 55–59.

Marx, Karl. 2010. The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte. In Surveys from Exile, ed. David Fernbach, 129–217. Verso Books.

Moore, Michael. 2016. “Morning After To-Do List,” Facebook, November 9, 2016, https://www.facebook.com/mmflint/posts/10153913074756857.

Muxeneder, Therese. 2019. “Ode to Napoleon Buonaparte (Lord Byron) for String Quartet (Orchestra), Piano and Reciter op. 41 (1942/43).” Kompositionen, Arnold Schönberg Center. German website. Last updated July 8, 2019. https://www.schoenberg.at/index.php/de/joomla-license-sp-1943310035/ode-to-napoleon-op-41-1942.

Palmer, James K. 2017. “Humorous Script Oppositions in Classical Instrumental Music.” Music Theory Online 23 (1). https://doi.org/10.30535/mto.23.1.4.

Schoenberg, Arnold. 1987. Arnold Schoenberg Letters. Edited by Erwin Stein. Translated by Eithne Wilkins and Ernst Kaiser. University of California Press.

—————. 2006. The Musical Idea and the Logic, Technique, and Art of Its Presentation. Edited by Patricia Carpenter and Severine Neff. Indiana University Press.

Shaw, Jennifer, and Joseph Auner, eds. 2010. The Cambridge Companion to Schoenberg. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CCOL9780521870498.

Stadler, Glen M. 1942. “‘New Order’ Dead Listed at 400,000: 175,000,000 More Europeans Held as Hostages in Nazis’ Occupation System.” New York Times, May 18, 1942.

Taruskin, Richard. 1997. “A Sturdy Bridge to the 21st Century.” New York Times, August 24, 1997.

Wiley, David. 1997. “Transcript of the David Foster Wallace Interview.” The Minnesota Daily, February 27, 1997.

Wlodarski, Amy Lynn. 2007. “‘An Idea Can Never Perish’: Memory, the Musical Idea, and Schoenberg’s A Survivor from Warsaw (1947).” Journal of Musicology 24 (4): 581–608. https://doi.org/10.1525/jm.2007.24.4.581.

Žižek, Slavoj. 2009. First as Tragedy, Then as Farce. Verso Books.

Footnotes

1. The New York Times’s film critic Bosley Crowther reviewed the movie as “a truly superb accomplishment” (1940). The movie became one of the top grossing films in 1941 (“Film Money-Makers Selected by Variety: ‘Sergeant York’ Top Picture, Gary Cooper Leading Star,” 1941).

Return to text

2. The Three Stooges’ film You Natzy Spy! (1940) is another example of a satirical movie that was used to protest the Nazi regime during the Second World War.

Return to text

3. Schoenberg seemed to have admired Chaplin for a long time, calling him an “exceptionally gifted personality” in his ‘‘Draft for a Speech on the Theme of the Talking Film” in February 1927 (Auner 2003, 196).

Return to text

4. Chaplin writes in his autobiography that “Hanns Eisler brought Schoenberg to my studio [of The Great Dictator]” (1964, 430). He also notes that he “had seen [Schoenberg] regularly at the Los Angeles tennis tournaments sitting alone in the bleachers wearing a white cap and a T-shirt” (430).

Return to text

5. It is worth noting that there are scholars who consider Ode to Napoleon as a form of sincere criticism. For example, Malcolm MacDonald describes the composition as the “outpouring of passionate scorn” (2008, 220).

Return to text

6. Schoenberg’s leitmotivic partitioning and uninterrupted progression towards a full twelve-tone row in Survivor present a case of composing out a “musical idea,” a method of composition that he advocated throughout his lifetime (Schoenberg 2006; Boss 2014).

Return to text

7. See, for instance, Stadler 1942 and “1,000,000 Jews Slain by Nazis, Report Says: ‘Slaughterhouse’ of Europe Under Hitler Described at London,” 1942.

Return to text

8. Hansen’s singing style for “War’n Sie” resembles Ode’s Sprechstimme, which might provide an additional connection between the two pieces. The recording for “War’n Sie” is available here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pkEbzeBF9iM.

Return to text

9. Even though satire and irony may be considered as distinct genres in literary theory, I treat the two terms interchangeably and consider them to be within the “humor spectrum” (Palmer 2017, [2.1]).

Return to text

10. While his use of musical artifacts from the tonal period has drawn scholarly attention, earlier analyses seem to seek historical and cultural meanings before investigating larger musical implications.

Return to text

11. In addition, MacDonald groups Ode to Napoleon together with other compositions that use tonal elements, such as Kol Nidre (1938) and Variation on a Recitative (1941) and constructs a narrative that claims that “[Schoenberg] felt able to return to tonal composition in the more traditional sense” (2008, 155).

Return to text

12. The association between Ode and Beethoven has been widely accepted among musicologists. The German version of the Arnold Schönberg Center’s webpage on Ode begins by discussing the nineteenth-century perception of Beethoven before discussing Schoenberg or Ode (Muxeneder 2019). The English version of the same page associates the piece with the “day of infamy” speech and then discusses the Beethoven quotation (Crittenden 2019). Although Schoenberg never wrote specifically about the connection between this composition and Beethoven’s music, the connection between Great Britain’s “V for Victory” campaign in 1941 and the opening theme of Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony through the letter V in Morse code (

Return to text

13. That this composition was conceived around the time of the “day of infamy” speech by Franklin D. Roosevelt further supports this interpretation.

Return to text

14. Föllmi interprets all of the tonal references in Ode on the basis of the final chord: “Die tonalen Bezüge sind im ganzen Verlauf des Werkes so stark präsent, daß sie nicht als Parodiesignale fungieren können; sonst müßte ja der Schluß der Ode, in strahlendem Es-Dur, die Bedeutung von George Washington desavouieren—aber das hieße, das ganze Werk in Frage stellen” (2002, 99).

Return to text

15. As Johnson 2001 shows, this way of attack is one of Karl Kraus’s methods of satire, in addition to blatantly juxtaposing incongruent styles. I will return to this point in [2.3].

Return to text

16. Jack Boss interprets the three movements of the Satires as (1) the presentation of the two compositional styles, followed by (2) an example of the “wrong” way to do it, ending with (3) the demonstration of the “right” way to do it. Schoenberg’s comment on the second movement––that it is purely visual and “was never intended by myself to be sung or performed” (1987, 272)––supports Boss’s reading.

Return to text

17. As characterized in Boss 2014 (180–242), this is Schoenberg’s demonstration of one such “right” way to write neo-classical music, to express of a “musical idea” through hexachordal inversional combinatoriality.

Return to text

18. The gesture in m. 145 above the word “him” is a near-identical repetition of m. 82.

Return to text

19. This passage seems to have been worked out by Schoenberg in MS 815. The theme of La Marseillaise in Ode is discussed in Föllmi 2002 as a signifier of the French Revolution and ultimately represents the free world against the Nazi regime. The Beethoven quotation that immediately follows is associated with victory. Altogether, Föllmi interprets this passage as a sincere praise of the Allies.

Return to text

20. Kraus’s influence on Schoenberg’s musical thinking is well known and discussed by Alexander Goehr (1985) and Julian Johnson (2001), among others. Schoenberg also expressed his intellectual debt to Kraus on many occasions (Johnson 2001, 105; Auner 2003, 8–9).

Return to text

21. The passage surrounding m. 145 will not be analyzed here because it is a near-identical repetition of m. 82.

Return to text

22. It seems that, while making MS 766, Schoenberg realized that the same four hexachords return, and MS 767 shows him figuring out why this was the case. But it is also highly likely that the composer already knew of the hexatonic scale’s symmetric property. The manuscript pages are evidence of him looking for further attributes.

Return to text

23. The antecedents have different versions—labeled a, b, and c—based on different orderings of the chord tones.

Return to text

24. The manuscript page MS 766 shows this relation more clearly.

Return to text

25. The hexachord 6-20 can project six unique major or minor triads and two unique augmented triads.

Return to text

26. The

Return to text

27. For example, according to Boss (2014, 395–425), the ideal shape for Schoenberg’s String Trio op. 45 (1946) is a complete horizontal presentation of the eighteen-tone row.

Return to text

28. In comparing Survivor with Steve Reich’s Different Trains, Richard Taruskin (1997) criticizes the narrative immediacy in Survivor’s musical portrayals of the concentration camp as being “B-movie clichés.” The criticism suggests, however, that Survivor’s music successfully depicts the scene; one can understand the music without knowing the intricate twelve-tone compositional method, which cannot be said for many of Schoenberg’s other twelve-tone compositions.

Return to text

29. In earlier research, Survivor’s compositional method had been mischaracterized as tonally oriented during the prayer section. As Wlodarski (2007) correctly points out, however, the entire composition is written with the twelve-tone method.

Return to text

30. Yuri Cholopov summarizes the two views on Ode’s compositional method: (1) “ein dodekaphones Werk mit einer Grundreihe” (a twelve-tone composition with a basic row) or (2) “ein Zwölftonwerk, jedoch ohne Grundreihe, oder dieselbe erscheint nicht bzw. nur in segmentierter Form” (a twelve-tone composition, however without a basic row, or one which doesn’t appear as such, only in segmented form.) (2002, 70). Joe Argentino (2019, 106n9) also summarizes different rows that were associated with Ode by various music analysts. One of the reasons for the twelve-tone methodological uncertainty in Ode can be attributed to the “contextual invariance” of the primary hexachord, as discussed in Argentino 2019.

Return to text

31. Schoenberg’s fair copy (MS 734) of this section contains identical notes, which suggests that the differences between the first draft and published score are not the result of typographical mistakes but rather intentional revisions by the composer.

Return to text

32. Schoenberg’s handwriting for the cello’s last note in m. 38 might look like an

Return to text

33. The triad can be constructed with the piano’s

Return to text

34. The narration section can be further divided, as Wlodarsky (2007) and Argentino (2013) suggest. However, they present different subdivisions of the narration section. Nevertheless, the large division between the narration section and prayer section is unmistakably apparent. I am only considering these two large sections.

Return to text

35. Example 13 is simplified to allow readers to recognize the row forms easily. The choir’s row form is omitted, because it is a horizontal presentation of P10. In m. 83 of the example, the dark green and dark blue boxes are in gradients because the notes alternate between the two boxes by moving half steps (i.e., D and

Return to text

36. The trichords belong to set classes 3-5 (016) and 3-4 (015), respectively.

Return to text

37. The dyadic partition’s ic1 and ic4 can be interpreted as the remnant of the ideal shape’s two set classes, 3-1 (012) and 3-3 (014), which feature the two dyadic interval classes prominently.

Return to text

38. Marx’s original statement appears in Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte (2010, 146), where he analyzes the authoritarian rule of Charles-Louis Napoleon Bonaparte, a nephew of Napoleon Bonaparte. In Marx’s statement, the tragedy refers to Napoleon Bonaparte and the farce refers to his nephew.

Return to text

39. Žižek argues that the belief that we are on the right side of history and that there will be a light at the end of the tunnel will, paradoxically, engender naïve inaction among the liberal public. He claims that history is not “on our side” and that “the light at the end of the tunnel is

Return to text

Copyright Statement

Copyright © 2020 by the Society for Music Theory. All rights reserved.

[1] Copyrights for individual items published in Music Theory Online (MTO) are held by their authors. Items appearing in MTO may be saved and stored in electronic or paper form, and may be shared among individuals for purposes of scholarly research or discussion, but may not be republished in any form, electronic or print, without prior, written permission from the author(s), and advance notification of the editors of MTO.

[2] Any redistributed form of items published in MTO must include the following information in a form appropriate to the medium in which the items are to appear:

This item appeared in Music Theory Online in [VOLUME #, ISSUE #] on [DAY/MONTH/YEAR]. It was authored by [FULL NAME, EMAIL ADDRESS], with whose written permission it is reprinted here.

[3] Libraries may archive issues of MTO in electronic or paper form for public access so long as each issue is stored in its entirety, and no access fee is charged. Exceptions to these requirements must be approved in writing by the editors of MTO, who will act in accordance with the decisions of the Society for Music Theory.

This document and all portions thereof are protected by U.S. and international copyright laws. Material contained herein may be copied and/or distributed for research purposes only.

Prepared by Sam Reenan, Editorial Assistant

Number of visits:

11338