Pen, Paper, Steel: Visualizing Bach’s Polyphony at the Bauhaus*

Stephanie Probst

KEYWORDS: artistic visualizations of music, graphs, sculpture, Linear Counterpoint, Bauhaus, Gestalt theory, Johann Sebastian Bach, Ferruccio Busoni, Ernst Kurth, Paul Klee, Henrik Neugeboren

ABSTRACT: Graphs drawn on rastered paper and a monumental steel sculpture display how visual artists Paul Klee and Henrik Neugeboren conceived of Johann Sebastian Bach’s polyphonic style in 1920s Germany. Focusing on the representational decisions behind these artistic translations of music, this article explores the ways in which such artifacts manifest a specific analytical lens. It highlights congruencies with and deviations from the theoretical framework of “linear counterpoint,” as epitomized in Ernst Kurth’s influential treatise from 1917, and thereby positions the artworks within the controversial reception history of Bach’s music and attendant theoretical frameworks in the early twentieth century. More generally, the article proposes that graphical and sculptural renderings of music can offer the opportunity to investigate music theory’s intangible methods and conceptual metaphors through different sensory experiences.

DOI: 10.30535/mto.26.4.6

Copyright © 2020 Society for Music Theory

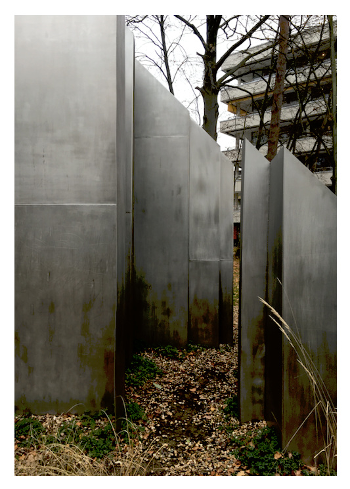

Example 1. Henrik Neugeboren, sculpture “Hommage à J. S. Bach,” Leverkusen (photograph by the author)

(click to enlarge)

[1.1] In the German town of Leverkusen, just outside of Cologne, one can visit a fugue by Johann Sebastian Bach. A steel sculpture in the park abutting the local hospital represents an excerpt of the Fugue in E-flat minor (BWV 853) from The Well-Tempered Clavier, Book 1, specifically the stretto maestrale at mm. 52–55 (Example 1).(1) Based on a sketch by the Transylvanian visual artist, pianist, and composer Henrik (Heinrich) Neugeboren (1901–1959), the sculpture allows passers-by to physically move through Bach’s stretto, as they wander in the space between the walls representing the voices of the contrapuntal texture. Titled “Hommage à J. S. Bach” in the few written documents referring to it, the sculpture lacks any manner of inscription or sign to identify its artist or subject on site (perhaps so as not to distract from the signage pointing to various hospital units). Neugeboren had devised the Hommage during a visit to the Bauhaus school in Dessau in 1928, but its realization in Leverkusen came only in 1970, over a decade after the artist’s death.(2)

[1.2] Certainly, it is no ordinary plastic tribute to Bach. Neugeboren shunned the idea of memorializing the composer’s physiognomy through yet another supersized bust—a trope he snidely dismissed as “a tawdry figure with sheet music on a pedestal” (1929, 19).(3) Rather, as Neugeboren discussed in an article published in the Bauhaus journal in 1929, Bach’s craft itself, and especially his polyphonic style, was the intended object of commemoration. As Neugeboren put it, he aspired to render visible “Bach’s combinatorial mastery” (19).(4)

[1.3] Already this sophisticated claim suggests an intricate conceptual underpinning to the sculpture, one that entailed careful artistic and theoretical consideration on different levels. In general, such processes are integral to the ambition of “visualizing the musical object,” as Judy Lochhead reminds us: “To visualize implies more than simply seeing, it implies ‘making’ something that can be seen

[1.4] This reading, and, indeed, the artwork itself, relies on a variety of cultural-historical premises. First, the very idea of rigorously translating music into different artistic media has roots in the aesthetic and ideological interventions of early twentieth-century Modernism. I will start by reviewing how the Bauhaus school, as the site where Neugeboren not only published the plans for his monument but where he also elaborated them in the first place, offered a particularly fertile ground for such a project. In that context, another example of an artist visualizing Bach’s polyphony at the Bauhaus will help to illustrate the artistic ambitions behind such endeavors and the specific attraction of that musical heritage. As one of the school’s influential teachers from 1921, Paul Klee worked with his students on translating two measures from a Sonata for violin and harpsichord into a graphical system. In a next step, the immediate comparability of the two artistic renditions—one by Neugeboren, the other by Klee—catapults them both into cultural contexts well beyond the visual arts, including the contentious landscape of Bach reception in 1920s Germany. As we shall see, the two artists shared specific music-analytical assumptions on that repertoire, but enacted them in manifestly different ways. Through this juxtaposition, some of the controversial issues fervently debated by music theorists at the time come to life in readily graspable ways. As material artefacts, these visual translations of music thus not only complement the written documentation of music theory, they also offer the possibility of experiencing the affordances and constraints of music-analytical perspectives through different sense modalities. Examining these artistic objects from a music-theoretical vantage point, in short, can sharpen our perception of the ways in which art and music can be mutually illuminating, not only on a creative level, but also on a conceptual one.(6)

At the Bauhaus, between the Arts

[2.1] The shared institutional backdrop to the two examples is more than mere coincidence. Around the turn of the twentieth century the seismic shifts that undid conventional artistic forms and genres also shook up long-established divisions between the arts, as Daniel Albright has exemplarily discussed.(7) These trends of Modernism affected all the arts and at once brought them closer together. A particularly vibrant hub of such endeavors was the famous Bauhaus school. Founded by Walter Gropius in Weimar in 1919, the Bauhaus moved to its purpose-built complex in Dessau in 1925, where it lasted until the Nazi party forced its relocation to Berlin in 1932, only to close it down definitively ten months later. But these constrains and the political opposition certainly haven’t diminished the lasting impact of the school on developments in art and design across the past century and up until today, as various exhibitions and catalogues in honor of its centennial celebrations document around the world. Though by no means unified by a single aesthetic ideology, the Bauhaus as a whole promoted the idea of bridging the fine and applied arts, their media and materials, allowing dance, music, weaving, design, architecture, painting, sculpting, and carpentry to meet in shared aesthetic and technical principles. These interartistic ambitions manifest in different ways in the extant sources. In his Bauhaus-treatise Point and Line to Plane (1926), for instance, painter Wassily Kandinsky studied forms and structures in music and dance in order to derive general principles behind the essential graphical parameters of point, line, and plane. Klee (1922, 1925) explored the pictorial potentialities of these elements in somewhat more experimental ways, but ultimately to the same end: to liberate the foundational graphical means from their conventional ties and thereby to profoundly enrich the visual arts.

[2.2] Notwithstanding this innovative zeal, old models from across all forms of artistic expression remained vital sources of inspiration and reference. Together with European capitals from Paris to Prague, the Bauhaus emerged as one of the centers of artistic engagement with the musical legacy of J. S. Bach.(8) Among the numerous influential teachers that the school attracted, Klee, Johannes Itten, and Lyonel Feininger were particularly prolific in this regard.(9) Feininger even took to composing fugues for piano and for organ in a Bachian style, and professed a general spiritual alliance with the composer that animated his pictorial work.(10) Klee, meanwhile, explored affinities with Bach’s music from artistic, theoretical, pedagogical, and performative vantage points.

Graphing Bach 1: Klee

Example 2. Paul Klee, Beiträge zur bildnerischen Formlehre (1922, BF/55): Graphic translation of J. S. Bach, Adagio from Sonata for Violin and Harpsichord (BWV 1019), mm. 1–2

(click to enlarge)

Example 3. J. S. Bach, Sonata for Violin and Harpsichord (BWV 1019), Adagio, mm. 1–2

(click to enlarge)

Example 2a. Detail from the bottom of Example 2, where Klee marked metrical hierarchies through beams of varying thickness

(click to enlarge)

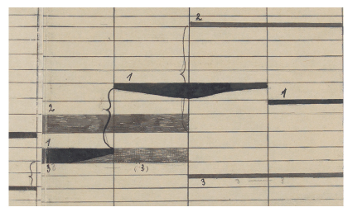

[3.1] Like many of his fellow teachers at the Bauhaus, painter Paul Klee (1879–1940) was also an avid musician.(11) Professionally trained as a violinist and married to the pianist Lily (née Stumpf), Klee integrated his passion for music into the curriculum of his graphical workshop. In January 1922, he dedicated two sessions of his introductory course to exploring modes for capturing music through graphical means, as documented in his lecture notes, which are collated under the title Beiträge zur bildnerischen Formlehre (1922, BF/44–57, esp. BF/55). After some general remarks about the division of musical time into rhythmic and metrical structures, Klee and his students devised a schematic layout for the graphical translation of music. Like in most forms of music notation, it is a two-dimensional graph with axes denoting time and pitch. The hand-drawn grid leaves room on the top for a transcription of the respective score on a conventional staff.

[3.2] In a next step, Klee mapped a specific musical composition into this grid (Example 2). For this notational exercise, he selected an excerpt from Bach’s Sonata for Violin and Harpsichord in G major (BWV 1019), specifically the opening two measures of the Adagio movement (see Example 3). The diagrammatic depiction (Example 2) translates the durations of the individual tones into horizontal beams of varying length. The thickness and shape of these lines seems to reflect two different factors, both informed by Klee’s musical expertise. Overall, Klee differentiated between a melody and accompaniment in this contrapuntal texture through the shape of the respective lines. The two wavy lines highlight the imitative relationship between the harpsichord’s right hand and the violin, while the accompanimental eighth notes of the other parts are rendered with straight lines. The juxtaposition of these two characters conversely provided one of the pedagogical hooks of this particular example: Klee generalized the interplay between melody and accompaniment to what he called “individualistic” and “structural” elements, which, in turn, transferred easily into visual-artistic practice.(12) For both voices, Klee chose a “qualitative” rather than merely a “quantitative” form of representation, by which he referred to the weight assigned to each tone in accordance with its metrical placement. These metrical hierarchies are schematically rendered on the bottom of the graph through the grey-shaded beams of varying thickness (Example 2a). Klee explained:

Since music sounds mechanical and free of expression when played without dynamics, I choose the qualitative representation and render the line with more or less weight, in analogy with the tone quality, while the quantitative form of representation

. . . is indicated through the vertical delineation of measures and their subdivisions. (1922, BF/54)(13)

[3.3] In the visualization, the straight lines of the accompanimental parts reflect these “qualitative” gradations through their varying thickness. But with the “individualistic” parts that carry the melody, Klee treated this variation much more freely. Here in particular, his experience as a violinist manifests itself in the expressive shape of the respective lines. It shows how the music accumulates and releases energy and tension (or “weight,” as Klee referred to it in the above quotation) along the way, often in the swells in the middle of sustained and syncopated tones. Essentially, Klee transferred the pressure of the bow on the string to the pressure of the pen on the paper. As art historian Régine Bonnefoit has pointed out, Kandinsky suggested precisely such a translation as a means of notation in Point and Line to Plane. In the context of outlining the expressive potential of the line, Kandinsky declared, “The pressure of the hand on the bow corresponds exactly to the pressure of the hand on the pencil” (1926, 99).(14) Bonnefoit (2009, 149) has also drawn attention to a later abstract painting by Klee, in which he enacted the same idea again under the title Heroische Bogenstriche (Heroic Strokes of the Bow) (1938).(15) In the painting, Klee applied the physical, embodied gestures of bow strokes through brush strokes onto the canvas, which materialize as lines of varying curvature and thickness.

[3.4] This analogy between violin playing and painting sheds light on a peculiarity in Klee’s visualization of Bach’s Adagio. In the graph, Klee bestowed a similarly expressive line to the melody when it first occurs in the harpsichord, even though the harpsichordist’s—or even a pianist’s—possibilities are ostensibly much more limited than a violinist’s when it comes to playing expressive swells in the middle of sustained tones. This is even more striking considering that the harpsichord introduces the melody first, and thus its line does not just mimic the violin’s version of the melody but rather anticipates it. A respective contemplation of the acoustic and mechanical capabilities of different instruments in terms of their graphical representation again features in Kandinsky’s treatise, which differentiated between point-instruments—with the piano as his example—and line-instruments, such as the organ.(16) In his own visualization of excerpts from the first movement of Ludwig van Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony, however, Kandinsky surrendered this classification in favor of differentiating expressive characters in the music through the juxtaposition of the point and the line as graphical symbols.(17) Klee, as well, evidently transcended concerns with the acoustic generation of sounds. Rather, he renders an overtly idealistic interpretation of the music by offering guidance towards a specific hearing of the piece. In that way, Klee’s visualization coheres with one of the primary definitions of music analysis and theory. It addresses the listener as much as the performer, who—whether a violinist or harpsichordist—ought to imagine expressive variations in the weight of the tones, and to tie them together into a musical phrase, regardless of the ways in which the sounds are produced. We shall come back to the relevance of such activities of auditory imagination below. The expressive nuance in Klee’s graph certainly illustrates that he did not simply “translate” from the score, but rather sought to capture a specific sonic interpretation of the music.

Example 2b. Detail of Example 2, showing the diatonic gradations on Klee’s vertical axis, with chromatic alterations (

(click to enlarge)

[3.5] Comparing the expressive graphical lines of the violin’s and the harpsichord’s presentation of the theme also exposes another idiosyncrasy of Klee’s translation. While the internal pitch relationships are exactly the same between the two utterances, the graphical line appears somewhat skewed in the second measure compared to the first, with some of the black horizontal bars bending downwards rather than upwards. This is to accommodate the chromatic inflections (the syncopated

[3.6] Overall, Klee drew attention in particular to the continuity of the individual melodic parts. In the graph, each horizontal line corresponding to a tone is annotated with a number to identify which of the three voices—from high to low—it belongs to (see detail of Example 2c). Klee graphically highlighted through a dotted line how the harpsichord’s right-hand part continues across the rest in m. 2, thus ensuring that its coherence is readily visible (Example 2d). The four vertical wavy brackets, meanwhile, tie the lines together across large melodic leaps or in instances in which two voices cross each other in register (Example 2c). Klee thus meticulously employed graphical means to represent the polyphonic voices as discrete and coherent entities. Precisely this emphasis on the horizontal trajectory of each voice in the contrapuntal musical texture constitutes an important parallel with the following example, with which we return to Neugeboren.

Example 2c. Detail of Example 2; vertical brackets at the beginning of m. 2 help to distinguish between the harpsichord’s right hand and the violin’s part (click to enlarge) | Example 2d. Detail of Example 2, showing Klee’s annotation of the rest in the harpsichord’s right hand in measure 2 (“zweite Stimme pausiert”), with a dotted line connecting across it (click to enlarge) |

Graphing Bach 2: Neugeboren

[4.1] For a young musician in the 1920s with artistic aspirations and a declared predilection for the music of Bach, a visit to the Bauhaus would have been an obvious step. In 1928, Henrik Neugeboren visited the school in Dessau, an occasion that marked his turn from being active primarily as a musician to becoming equally prolific as an artist.(18) The next year, he moved to Paris, where he settled for the rest of his life, adopting the name Henri Nouveau and dedicating his time and creative energy to composing, painting, sculpting, and writing. Neugeboren’s early training had focused on music. From 1921–25, he studied in Berlin with Ferruccio Busoni, composer Paul Juon, and pianist Egon Petri, and in the following years he became a student in the master class of Nadia Boulanger in Paris.(19) Neugeboren’s veneration for Bach might have been fostered as much by the enthusiastic reception of that musical heritage at the Bauhaus as by the activities and aesthetics of his teachers Busoni and Petri. After all, the latter two had been working on an edition of Bach’s piano music, with ample analytical and interpretative commentary.(20) In that context, Busoni’s advice on the Fugue in E-flat minor (BWV 853) of The Well-Tempered Clavier reads, “Special attention should be paid to the masterly construction of the Fugue” (1894, 51n2; italics in the original). Featuring that particular fugue, Neugeboren’s description of his project echoes Busoni’s declaration, stating that he aimed for rendering visible the “construction” of Bach’s music in an “instructive” way.(21)

[4.2] For Neugeboren, the concern with the “construction” of Bach’s music is symptomatic as well of the broader aesthetic commitment in which he framed his ambitions. Like many of his contemporaries, he took special interest in the “mathematical”—or, as cited earlier “combinatorial”—properties of Bach’s music, explaining that his own renditions illustrate such qualities as they had been explored in the research of Wilhelm Werker and Wolfgang Graeser.(22) For his groundbreaking edition of The Art of Fugue (1924), Graeser had studied the combinatorial organization of that work, while Werker highlighted aspects of symmetry—often in diagrammatic sketches—in The Well-Tempered Clavier (1922).(23) Peter Vergo (2010, 233) has suggested Iwan Knorr’s textbook Die Fugen des “Wohltemperierten Klaviers” von Joh. Seb. Bach in bildlicher Darstellung (The Fugues from Joh. Seb. Bach’s Well-Tempered Clavier Graphically Depicted) (1912) as another possible reference to Neugeboren. Like Werker, Knorr used diagrams to analyze structural features of Bach’s polyphonic compositions.(24) All of these authors, including, a little later, Joseph Schillinger in New York, probed Bach’s polyphony for its mathematical logic, usually through geometrical depictions.(25)

[4.3] Neugeboren was not only part of this collective impulse to subsume Bach’s music under a mathematically founded worldview, but he also extended it to imply a certain methodological standard. As he elaborated, he viewed his renditions as “a scientifically precise translation [of the music] into another system” that was “free of fictions” rather than “an emotionally charged individualistic reinterpretation” (1929, 16).(26) This claim of scientific precision and the distinction between a “translation” [Übertragung] and “reinterpretation” [Umdeutung] appeal to the allure of objectivity, which had been in vogue at least since the precision instruments of the 1850s were used to eradicate human bias in different processes of representation (Daston and Galison 2007). While Klee, too, had described his visualization of Bach’s music as a “translation” [Übersetzung], Neugeboren positioned his project in notably different terms. In Klee’s case, the object of translation was quite expressly an “individualistic” interpretation of the music, deriving from the way in which the artist might have played the piece on his violin. Neugeboren, by comparison, strove for a purportedly more clinical, quasi-objective rendering—though, as I shall argue, it was no less interpretative than Klee’s.

Example 4. Henrik Neugeboren (1929, 18), visualization of J. S. Bach, Fugue in E-flat minor (BWV 853), stretto at mm. 61.3–67

(click to enlarge)

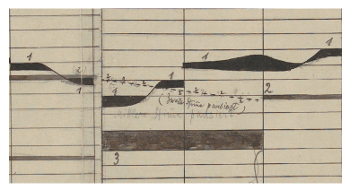

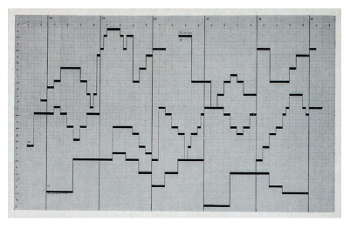

[4.4] Some aspects of Neugeboren’s rationale and its difference from that of Klee come to the fore already in the schematic layout of the graphs that he prepared of select passages from Bach’s E-flat minor Fugue, such as the one in Example 4. One of these graphs would become the basis for sketches for the sculpture shown in Example 1.

Example 4a. Detail of Neugeboren’s graph in Example 4, showing chromatic gradations on the vertical axis

(click to enlarge)

[4.5] A background of scaled paper provides the two-dimensional grid onto which Neugeboren mapped Bach’s music. Again, as in conventional music notation, the two axes denote time and pitch. The gradation of these axes, meanwhile, served the artist to rectify what he perceived as shortcomings of staff notation with respect to the musical parameters of pitch and duration. First, Neugeboren criticized the visual illusion of presenting chromatically altered tones on the same staff line even though they are patently different pitches. In his own approach, he released pitch from these ties and distributed it instead in continuous chromatic gradations (the gradations are marked on the vertical axis on the left from bottom to top, see Example 4a). Second, Neugeboren explained that he sought to “optically translate the full extension of the acoustic process, rather than to merely indicate it through graphical symbols” (1929, 16).(27) Instead of encoding the duration of individual tones through note heads of different color and the addition of beams, flags, and dots, he rendered duration through the length of the horizontal lines that he drew, adhering rigorously to the subdivisions of the underlying grid. This aspect closely resembles Klee’s form of representation, as we saw earlier. Showing tones in their “absolute” extension and position in pitch space, Neugeboren conceived of his graphs as making the music as “directly and variously accessible to the eye as to ear,” facilitating a “heightened level of comprehension” (1929, 16).(28)

[4.6] While positioning his approach against the graphical representation of the music in the score and negotiating its visual appearance in seemingly abstract terms, Neugeboren’s rendition still relied on an interpretative, if not analytical, intervention. After all, the artist not only transcribed the tones of the musical score in their pitch and duration, but also tied them together into graphical—and, by implication, musical—entities (just as we saw in Klee’s graph). Indeed, Neugeboren also acknowledged the interpretative quality of his rendition, in that it prioritizes certain musical qualities over others. A particular feature in his graphs concerns the horizontal dimension:

Now

. . . one can see the course of every voice as a continuous, rising and falling, colored line; in this [approach] it was intended for the horizontal process to stand out in particular. (1929, 16)(29)

The emphasis on the “horizontal process” ensues from connecting the horizontal lines that represent the individual tones through vertical lines. The resulting linear shapes trace the different polyphonic voices and isolate them as quasi-independent strata from the musical texture. Neugeboren envisioned differentiating these lines further through the use of colors and allowing them to be followed continuously, without “nettlesome interruptions and page-turns” (1929, 16),(30) through a scroll-like layout of the graphing paper. While neither of these latter ideas was enacted in the black-and-white reproductions for the article in the Bauhaus journal, their effect can be gleaned from a sketch that Neugeboren prepared of the entire C major Fugue from The Well-Tempered Clavier 1 (BWV 846), which is preserved at the Bauhaus archive.(31)

[4.7] In these renditions, not only the horizontal process of the music comes to life, but also the interrelation of the voices. Giving each part a distinct shape, the continuous lines capture in visual form the correlation of motives and themes across the voices, as well as their transformation. In the passage shown in Example 4, for instance, the alto part features the fugue subject, while the bass presents its augmentation. About midway through the excerpt (at m. 64.3), the soprano enters with the theme in inversion. Neugeboren’s graph exposes these contrapuntal procedures in terms of their corresponding geometrical operations of mirroring and magnification.

[4.8] The effect of bringing out these relationships relies as much on the layout of the graphs as on the selection of music featured in them. With respect to the choice of fugues that he deemed worthy of his graphical-geometrical approach, Neugeboren might once again have been guided by his teacher. In addition to the “masterly construction” of the E-flat minor Fugue, as mentioned above, Busoni lauded its “architectural style” (1894, 7). This quality elevated the Fugue to “the most important in the Book—perhaps in the whole First Part,” a rank that Busoni found matched only by the “architectonically perfect” C major Fugue (BWV 846) (50).(32) Neugeboren dedicated two-dimensional graphs to precisely these two “architecturally” notable fugues. While the graph of the C major Fugue is dated “May 3, 1944,” it was the E-flat minor Fugue that features in his earlier project for the Bauhaus journal (1929). For that publication, Neugeboren focused on three select stretto passages, as sections of the greatest combinatorial interest. Two of these are rendered only in two-dimensional graphs, such as the one reproduced in Example 4, while for the third, the climactic stretto maestrale—“one of the highpoints of the fugue” (1929, 19)(33)—the graph served as the base plan for the sculpture shown in Example 1.(34) I will attend to the design and import of the sculpture in more detail at the end of this article.

[4.9] The choice of these three excerpts shows that Neugeboren founded his renditions on his own analysis of the music, in accordance with the aesthetic predilection of his project. Here, his agenda deviates from the analysis that Busoni provided in the commentary of his edition.(35) Busoni’s (1894, 50–51) interest in the “architecture” of the composition focused on the symmetrical arrangement of the three sections that make up the development of the fugue in mm. 19–61. The stretti contained in this formal part feature first the superimposition of the theme in similar motion (mm. 19.3–29), and then in contrary motion (mm. 44.3–50). In most of these instances, only two voices participate in the stretto while the third accompanies freely (the only exception is in mm. 24–26, where all three voices enter with the subject at only a single beat apart).

Example 5. Henrik Neugeboren (1929, 18), visualization of J. S. Bach, Fugue in E-flat minor (BWV 853), stretto at mm. 77–83

(click to enlarge)

Example 6. J. S. Bach, Fugue in E-flat minor (BWV 853), mm. 75–end (comprising the excerpt shown in Example 5) (Busoni 1894, 53)

(click to enlarge)

[4.10] Neugeboren, by contrast, drew his examples from the last division of the E-flat minor Fugue, where the subject is presented in its greatest variety of contrapuntal transformations. As discussed in [4.7], the excerpt of Example 4 features the subject, its inversion, and augmentation. The second graph that Neugeboren reproduced in the Bauhaus journal is dedicated to the last stretto of the Fugue, mm. 77–83 (Example 5). Here, the augmentation occurs in the soprano, while the bass presents the fugue subject (Example 6). The alto introduces another, quasi-augmented variation of the subject with dotted quarter notes, which had occurred previously in the alto entrance in mm. 24–26 and, in inversion, in the soprano in the pickup to m. 48. In summary, the two stretti depicted in Neugeboren’s graphs (Examples 4 and 5) comprise three different forms of the theme each, allowing for a close comparison of their visual shapes.

[4.11] Example 5 moreover demonstrates the extent to which this form of visualization captures the linear coherence of each contrapuntal part, especially at moments of a crossover in register. At m. 80.3, for instance, the alto enters below the sounding note of the bass part (

Example 7a. Ferruccio Busoni (1894, 52), edited score of J. S. Bach, Fugue in E-flat minor (BWV 853), mm. 44–47

(click to enlarge)

Example 7b. Ferruccio Busoni (1894, 52), annotation to the excerpt in Example 7a, mm. 45–47, treble clefs are implied for both staves

(click to enlarge)

[4.12] This graphical separation of the different polyphonic voices at once projects the structural-geometrical logic discussed so far into a profoundly musical dimension. In this respect, Neugeboren’s graphs rigorously implement an idea that Busoni advocated in his edition of the piece. Referring to a similar passage (another stretto) earlier in the fugue in which two parts intersect in the same register (mm. 45–47), Busoni provided a clarifying transcription that isolates the two voices on separate staves (Examples 7a & b). Since one of them carries the theme, Busoni advised that it ought to be brought out in performance.(36) Omitting clefs and key signatures, Busoni’s transcription in Example 7b is helpful only as a supplement to the score above. Its main affordance is to bring out the linear continuity of the two upper voices, at the expense of showing the full musical texture and dividing it between two staves according to the player’s two hands. The focus is analytical, but only with respect to a certain aspect of the score—had Busoni included a third staff for the bass part, for instance, he could also have shown the parallel voice leading with the alto and the imitation between bass and soprano.

[4.13] These, in turn, are the qualities of Bach’s music that spring to the eye from the graphs that Neugeboren prepared of the fugue (Examples 4 and 5), and, as we saw earlier, also from Klee’s graphical rendition of Bach’s Sonata (Example 2). Rendering the full musical texture, these graphs show the distribution of all three parts in register (and pitch space, more generally), their horizontal coherence and their motivic relationships. Moreover, once readers have familiarized themselves with the shape of the theme or main subject, they should be able to make sense of the graphs in their own right, without further recourse to the score. In that regard, the artistic renditions take Busoni’s ideas further than what Busoni himself could achieve in his edition of the music. This very quality is where Neugeboren’s and Klee’s renditions meet, despite their otherwise overtly different aesthetic backdrops. They both prioritize the linear trajectory of the individual polyphonic voices in Bach’s music. As we shall see, the graphs also expose the limits of this approach, and they thereby capture what was at stake in negotiating ways of analyzing Bach’s counterpoint in the early twentieth century. Indeed, especially through their opposing aesthetic references, the two artistic projects mirror vivid music-theoretical debates at the time.

Between “Reckless” and “Linear” Polyphony: A Venture into Music Theory’s Aesthetic Debates

[5.1] Thanks to his outspokenness, Busoni supplied one of the catchphrases of these debates. In his “Selbst-Rezension” of 1912, published in Musikblätter des Anbruch in 1921, he reflected on the impact that his years of intensively studying Bach’s contrapuntal style had on his own compositions. As a particular quality of maturity, he considered how Bach’s music had taught him to a focus on linear-polyphonic processes in composition, trusting that feasible harmonies would ensue as a result. Busoni described this compositional approach as “reckless, uncompromising polyphony” (“rücksichtslose Polyphonie”; 1921, 23).(37) Though never denying the importance of an established harmonic framework, Busoni’s professed prioritization of linear-melodic over vertical-harmonic structures raised a red flag in 1920s Germany. Already in a generally favorable critique of Busoni’s Bach-editions, including an excursus on his compositions, August Halm had challenged the concept of “reckless polyphony,” wondering whether it could adequately capture the listener’s experience of the music.(38) Indeed, Halm maintained that his hearing was guided primarily by harmonic progressions even in two pieces that explore the limits of tonality—Bach’s chromatic Gigue from the English Suite No. 6 in D minor (BWV 811), which Halm described as “imbued with a lusty ugliness” (1921, 242),(39) and Busoni’s Fantasia contrappuntistica (BV 256, from 1910). While Halm thus cast doubt on “reckless polyphony” as a useful analytical category, the expression lent itself to much more sarcastic usage. Other contemporary critics, indeed, saw the attention on the linear-melodic organization of music—and especially of Bach’s polyphonic music—more categorically opposed to a harmonically founded analysis of that repertoire than Halm intimated. Theodor W. Adorno, for one, disparaged the “randomization” of harmony that resulted from a focus on voice leading.(40) This sensitivity, which escalated the centuries-old debate over the primacy of harmony or melody, was famously fueled in the 1920s by the work of Swiss music theorist Ernst Kurth.

[5.2] Much more thoroughly and vehemently than Busoni, Kurth promoted a linear-melodic perspective on Bach’s contrapuntal style in his 1917 treatise Grundlagen des linearen Kontrapunkts: Einführung in Stil und Technik von Bach’s melodischer Polyphonie. Foundations of Linear Counterpoint: Bach’s Melodic Polyphony, as it is commonly rendered in English (following the shortened title of its second edition of 1922), catapulted the designation of its title into musical discourse of the time.(41) As the more neutral analogue to “reckless polyphony,” “linear counterpoint”—and “linearity” more generally—came to epitomize one of the most notorious issues of contention between conservative and modernist camps that are documented in musicological discourse from the 1920s. The diverse agendas are encapsulated already in the history of the term. Alexander Rehding has traced the coinage of “linear counterpoint” to Rudolf Louis, citing passages from his inaugural dissertation Der Widerspruch in der Musik (1893) and his later Die deutsche Musik der Gegenwart (1909), where the term appeared with a “deliberate [

[5.3] The ensuing “ideologization” of these perspectives, as German musicologist Susanne Fontaine (2000, 398) has called it, involved both a clash of traditions within music theory, and the ramifications of these tensions in musical circles more broadly. Though relatively reconciliatory in tone, Kurth identified two authors who to him personified the harmony-centered understanding of counterpoint that he endeavored to overcome: Johann Joseph Fux and the doyen of German harmonic theory of the nineteenth century, Hugo Riemann. Paying tribute to the latter’s achievements at various occasions throughout the treatise, Kurth nevertheless took issue with Riemann’s approach of deriving polyphony from the gradual “figuration” of a harmonically structured texture (1922, 137–41).(44) To Kurth, this did not properly account for the essence of Bach’s polyphonic music, which—Kurth was certain—arose from the primacy of the melodic line. While conceiving his analytical apparatus as complementary to that of Riemann, Kurth objected more vehemently to the legacy of Fux’s Gradus ad Parnassum (1725).(45) That treatise and its didactic taxonomy of the five species [Gattungen] of contrapuntal composition codified what Kurth described as a moment-by-moment slicing of contrapuntal textures into vertical sonorities. Construing counterpoint through the juxtaposition of concurrent notes, this focus on the music’s vertical organization is allegorically captured by the “ominous principle of ‘punctus contra punctum’” (1922, 117–19).(46) As the target of his agenda, Kurth wittily countered this conception already on a linguistic level, by mediating the “point” in “counterpoint” through the “line” of “linear counterpoint.” Kurth further proposed the term “paralinear” to describe the polyphonic texture, by substituting both “contra” and “point” of “counterpoint” to emphasize the concurrence of multiple lines that develop simultaneously and as independently as possible.(47) In order to appreciate polyphony as a “paralinear” texture, Kurth concluded that the melodic line finally had to take precedence in conceptions of polyphony.(48) Indeed, the lines in “paralinear” textures should develop as freely and unbound by concerns of vertical coordination as possible: “The art of contrapuntal technique is the higher, the more freely and detached from all considerations of harmonic sonorities the development of lines can unfold” (1922, 102).(49) From such pronouncements, the path to the “randomization” of harmony caused by “reckless” polyphony does not seem so far away.

[5.4] Notably, both favorable and skeptical readers inferred that Linear Counterpoint invited such a radical interpretation. While some celebrated it for liberating harmony from restricting conventions, others deemed the concept responsible for a neglect of harmonic concerns. From the beginning, modernist composers, among them most famously Ernst Krenek, embraced the treatise as a source of inspiration, which reflected their creative approach.(50) The link to avant-garde trends was further forged by proponents of new music like Paul Bekker and Hans Mersmann, who adopted Kurth’s theory and terminology for the analysis of contemporary music.(51) Rehding has highlighted Bekker’s review (1918) of the treatise for “launch[ing] the active reception of what became known as ‘linear counterpoint’” (1995, 3 and 57) and for initiating an infusion of this new catchword into the volumes of many journals.(52) The volumes of the Neue Zeitschrift für Musik, particularly the issues between 1919 and 1926, are good examples, featuring scathing contributions from the likes of Alfred Heuß and Adolf Diesterweg.(53) Reacting to the enthusiastic reception of Linear Counterpoint in terms of a modernist aesthetic, these conservative critics decried the appeal of linearity in general and the trend of misappropriating historical references for contemporary compositional tendencies in particular, or—as Diesterweg put it—of “justifying a music that has been forcefully disrupted from any consideration of harmonic sensitivity” (1926, 220).(54) More specifically, a diatribe of Heuß’s—written in his powerful position as editor in chief of the Neue Zeitschrift für Musik—reveals the anxiety centered around the music of Bach as the contested cultural-political icon:

When, in reference to the melodic polyphony of Bach, the designation “linear counterpoint” was found, there was a big uproar of hoorays from these lowly creatures. Without further ado, they declared in their “independence” Sebastian Bach as their progenitor, and from then on carried themselves the more confident, self-possessed, and assured of a good future. (1923, 278)(55)

The conservative camp around Diesterweg and Heuß thus perceived the “lowly creatures” as encroaching on Bach’s legacy. While they sought to celebrate Bach as a progenitor to a specifically German cultural tradition, the internationalist orientation of modernism put this national heritage at stake, moreover threatening to deform it by claiming it as the basis to new stylistic, tonally suspended tendencies.(56)

[5.5] Through the triangulation of the references at play—Bach’s music, modernist aesthetics, and the theory of “linear counterpoint”—Kurth was inadvertently drawn into this ideological crossfire. The debates pitted the analytical framework of Linear Counterpoint against the cultural value attached to Bach’s oeuvre. In order to fend off Bach’s polyphonic music from modernist adaptation, the conservative critics willingly surrendered Kurth’s theoretical framework and thereby—ironically—dissociated it from what Kurth had declared as its unitary foundation. Kurth reacted to the oppositional reception of his theory in the preface to the third edition of his treatise (1927), where he confined its intended applicability to strictly tonal contexts (Rehding 1995, 5; Kampe 2014). He thereby distanced himself from the modernist appropriations of Linear Counterpoint and used the opportunity to reassert Bach’s music as the only true model of contrapuntal composition, which he saw as firmly grounded in functional harmony.(57)

Against the Point in Counterpoint: Hearing and Visualizing Linear Polyphony

[6.1] These music-theoretical debates offer a striking context for Neugeboren’s and Klee’s visualizations of Bach’s music. As noted above, both artists chose to represent Bach’s polyphony as a “paralinear” texture. Their visualizations, respectively of Bach’s sonata movement and of the E-flat minor fugue, clearly expose an analytical predilection that is fully consistent with Kurth’s theory. At least in Klee’s case, this reference is all but incidental, as Régine Bonnefoit (2009, 137–42) has argued: the example from Bildnerische Formlehre (Example 2) is one of many that show that Klee explored correlations with Kurth’s theory in his theoretical and creative oeuvre. Bonnefoit (2008, 121) points to the concept of “pictorial polyphony,” through which Klee described the possibility of a visual-artistic equivalent to Bach’s polyphonic style.(58) As she observes, the term denotes a texture that interweaves multiple autonomous linear entities, as employed in numerous paintings that pay tribute to Bach’s music. While Klee was most explicit about his alliance with Kurth’s theory, Bonnefoit has also traced references to Linear Counterpoint in the work of other artists, leading her to conclude that the treatise was a well-known source at the Bauhaus.(59) This might as well include Neugeboren, even though that artist indicated only other, more mathematically oriented studies as explicit sources of reference for his project. But Neugeboren’s analytical viewpoint accords just as comprehensively with the ideas discussed above as Klee’s. Indeed, the denser polyphonic textures that Neugeboren chose to depict bring out yet more clearly how he conceived and analyzed this music as an interweaving of lines, which develop as independently as possible. In short, both artists implemented Kurth’s vision of “penetrating counterpoint using the line as unit and primordial entity” to the fullest effect (1922, ix).(60)

[6.2] In Neugeboren’s adaptation, this idea takes on an idiosyncratic and distinctly modernist touch. The chromatic scale that determines the gradations of the vertical axis in the graphs (Example 4a) is significant in this respect. It indicates that Neugeboren projected his linear reading of Bach’s music into chromatic pitch space. By transgressing the tonal frame that Kurth conceived for his analytical apparatus, Neugeboren’s graphs thus typify the kind of modernist appropriation of linearity that derailed the reception of Kurth’s treatise in its own right. Klee’s traditionalist interpretation of Bach’s Sonata within the bounds of diatonic tonality, by contrast, accords with Kurth’s ideology, even if the artist failed to think of adjusting the layout of his graph to the required key (see Example 2b). In their juxtaposition, the two artistic renderings and their diatonic and chromatic backgrounds (comparing Examples 2b and 4a) thus epitomize the conflicts of appropriation that Kurth found himself drawn into. The two graphical approaches demonstrate how adaptable ideas of Linear Counterpoint prove as a conceptual frame within different aesthetic mindsets, and they thereby mirror the diverging ways in which the treatise was read by theorists and composers alike.

[6.3] Just as much as the music-theoretical debates situate these artistic endeavors in a broad cultural context, the graphical renditions, in turn, can illuminate music theory. Indeed, by translating its application into the visual realm, the graphs bring out the full consequences of Linear Counterpoint—including the alleged neglect of the vertical-harmonic dimension of the music. Looking back at Examples 1, 2, 4, and 5, it is indeed difficult to glean chordal structures. Although one could certainly reconstruct the underlying harmonies from these visual forms, this reading is not one that the layout facilitates. The predilection for depicting horizontal trajectories in the graphs makes it difficult to visualize chordal structures, even though harmony is essential to Bach’s stretti from a combinatorial point of view. This notational dilemma illustrates the extent to which a particular conceptual lens inevitably obscures certain other musical facets and thereby offers a powerful analogue to the concerns negotiated by music theorists of the day.

[6.4] As visual translations not only of Bach’s music, but also of a specific analytical approach, the artistic graphs become objects of music theory. More than that, they can serve to elucidate the conceptual foundation to Linear Counterpoint. While Kurth acknowledged that the expression “melodic line,” which so centrally encapsulates his theoretical apparatus, is “adopted from a geometrical viewpoint” (1922, 2),(61) he refrained from representing it graphically. Across the treatise, the musical examples are (at best) annotated with point-like symbols (such as + and * to highlight individual tones). In this context, the artistic renditions complement Kurth’s presentation of his theory. The graphs project the conceptual metaphor of the melodic line back into the visual domain from which it derived. In this constitution, we can observe the operative power of the image, its conceptual premise and affordance. The linear-horizontal strands in the graphs connect the individual tones into larger entities. These lines lend the fugal subject a distinct graphical shape, which remains recognizable regardless of its position in the geometrical plane. As a diagrammatic rendering of how the music ought to be heard and understood, the graphs suggest that when listening to Bach’s polyphonic texture, it is possible to isolate these linear strands and focus on them as horizontally evolving strata.

[6.5] A correlating theory that sought to explain precisely such cognitive processes in hearing melody was formulated in 1890 by Viennese philosopher Christian von Ehrenfels. In his article “Über ‘Gestaltqualitäten’” (On ‘Gestalt Qualities’) ([1890] 1988)—a foundational text for the formation of Gestalt psychology in German academia—Ehrenfels inquired into the principles by which such phenomena as melody, which develops over time, could be conceptualized as a unified whole. He suggested that melody must be perceived as a distinct mental image, which could be recognized by listeners even in altered forms, such as in transposition in pitch or timbre. Ehrenfels postulated two fundamental cognitive principles in this essay, both derived from melody as his central case study: “supra-summativity” describes that a melody is more than the sum of its constituent tones; the resulting holistic Gestalt, in turn, remains identifiable regardless of its transpositional level in pitch space, as captured by the principle of “transposibility.” Only following these explorations of auditory perception, Gestalt theorists turned to translating these questions to the visual realm. When Max Wertheimer (1922, 1923) codified laws of cognitive tendencies around the perception of Gestalten, for instance, he focused on visual phenomena and, accordingly, expressed his findings in graphical terms through formations of black dots on a white background.(62)

[6.6] In Neugeboren’s and Klee’s graphs analyzed above, we can appreciate the representation of the different polyphonic parts as unified geometrical shapes and as a direct translation of the Gestalt-psychological principles that Ehrenfels formulated for the perception of melody. By focusing on stretto passages, in which the subject is overlaid with variants of itself, Neugeboren’s graphs moreover show how the manipulated shapes that result from augmentation and inversion can be related to the theme’s original form. Indeed, it is also their adaptation of the chromatic framework that brings out these relationships with such clarity. Here, the comparison with Klee’s approach illuminates how the unevenness of the diatonic system inevitably skews the graphical representation of acoustic similarities. Even an adjustment of the diatonic scale (Example 2b) to match the key of the piece would not suffice to rectify the variance between the two iterations of the sonata’s theme, since they feature the common alterations of the sixth and seventh scale degrees in minor. Still, in both cases the visualization of Bach’s music as a “paralinear” texture—as Kurth preferred to call it—brings out the ways in which such a hearing relies on Gestalt-theoretical principles.

[6.7] This understanding corroborates research by Luitgard Schader and Daphne Tan, who have investigated the psychological foundations of Kurth’s theories. Focusing respectively on Linear Counterpoint and the late monograph Musikpsychologie (1931), both scholars have established correlations between Kurth’s ideas and the emergent field of Gestalt theory, including connections to the Viennese and Berlin schools of Gestalt psychology around Ehrenfels and Wertheimer.(63) In addition to the sources that Kurth quoted in Musikpsychologie, these readings are based on Kurth’s famously evocative language. Through an idiosyncratic assemblage of predominantly “energeticist” metaphors that notoriously characterize his writing, Kurth relayed what he considered the “psychological conditions” for the musical phenomena that he studied (1922, x).(64) Declarations such as “the unity of the linear motion as a primary phenomenon in contrast to the individual tones” (14),(65) for instance, not only signal Kurth’s alliance with Gestalt theory, but also capture the way in which he sought to convey his experience of listening to melody. Elsewhere, I have proposed that many of these experiential qualities that Kurth ascribed to melody converge in his notion of the “melodic line,” including the sensations of locomotion and of a continuous energetic process.(66) This accords with new theories of line from around 1900, such as Klee’s famous “walking line,” which no longer connects two predefined points but rather grows freely out of a single point through the propagation of energy and motion (Klee 1925, 6; see also Bonnefoit 2009, 8–11). Thought of as a graphical gesture, the line integrates the above perceptions into a single distinct shape and thus encapsulates the Gestalt quality of melody. While Kurth conceived of this imagery as symbolizing immaterial sensations that are rooted in the listener’s unconscious (and thus captured under the heading of a “psychological condition”), exploring its visual translation makes the Gestalt-theoretical tenet of Linear Counterpoint more palpable.(67)

[6.8] Indeed, the graphical renditions discussed above not only represent a paralinear analytical hearing of the underlying music, but they also call on the viewer to activate their auditory imagination. Precisely this engagement with the music resonates with the cognitive paradigm of early twentieth-century music theory and substantiates the conceptual nature of the melodic line as a mental image.(68) As the backbone to Kurth’s theory of Linear Counterpoint, the metaphor of the line encapsulates the internal sensations that melody and polyphony elicit in the listener. While Kurth eschewed its figurative representation and instead conjured the imagery through descriptive language, the visual artists encountered in this article explored ways of externalizing their experience of listening to Bach’s polyphony through graphical means. Manifesting the lines of Linear Counterpoint as visible marks, these artistic renditions transgress the inherent invisibility of Kurth’s theoretical framework. Thanks to this complementarity, they illuminate some of the theoretical premises in more drastic ways, such as the profoundly psychological conditions to the shared image of the melodic line.

A Haptic Encounter with (Linear) Polyphony

Example 8. Henrik Neugeboren, sculpture “Hommage à J. S. Bach,” Leverkusen, view from the side (photograph by the author)

(click to enlarge)

Example 9. Henrik Neugeboren, sculpture “Hommage à J. S. Bach,” Leverkusen, view from inside (photograph by the author)

(click to enlarge)

[7.1] With Neugeboren’s sculpture (Example 1), these imaginings materialize not only as images but also as a tangible object. The sculpture transcends the realm of two-dimensional inscriptions of music and facilitates a haptic encounter with Bach’s polyphony.(69) While it can certainly be assessed through the eyes alone, the sculpture affords different sensory modes of engagement than the graphs of Examples 2, 4, and 5. It can be touched, observed from different perspectives, and if you want, you can even position yourself within it. Moreover, since it is founded on a linear-horizontal analysis of the music, the sculpture brings to life the theory of linear counterpoint and makes it accessible in every sense of the word. Especially when looking at it from the side (as in Example 8), or when going inside (Example 9), the separation of the different voices becomes even more obvious than in a two-dimensional representation. In the sculpture, these linear entities transform into rigid, impenetrable barriers that dictate a single direction in which we can move through the texture—the same, horizontal, trajectory that Kurth advocated for listening to Bach’s polyphonic music.(70) Neugeboren’s design thereby potently displays the latent “recklessness” of “linear” polyphony. Still more striking than the two-dimensional graphs, the sculpture thus exposes the extent to which a focus on a linear hearing of Bach’s polyphony inevitably—and here literally—eclipses other aspects of the musical texture. At the same time, the fact that one can walk through the sculpture at all, between its linear walls, is possible only because the underlying music allows for it. Had Neugeboren chosen one of the musical excerpts that he depicted in Examples 4 and 5, where voices cross over in register, these moments would constitute transverse barricades and thereby obstruct the possibility of “penetrating counterpoint using the line [as the guiding principle],” as Kurth advised (1922, ix).

Example 10. J. S. Bach, Fugue in E-flat minor (BWV 853), mm. 52–55 (Busoni 1984, 52)

(click to enlarge)

[7.2] As the stretto maestrale of the E-flat minor Fugue, the excerpt that serves as the model for the sculpture features the parallelism of all three voices as they enter with the fugal subject at only a single beat apart, at first in its original form and then, in immediate succession, in inversion (see Example 10). Accordingly, the three rows of the sculpture outline essentially the same contour in their zig-zagged shapes, while taking occasional embellishments into account, such as the sixteenth-note figuration of the soprano in the third measure of the excerpt, which is rendered in the narrower zig-zags in the middle of the back row (see Example 1). The sculpture thus translates into the visual domain also the conceptual “parallelism” of the voices that characterizes the musical excerpt. Visually, this parallelism can be perceived from within—when walking through one of the sculpture’s two passageways—and from outside. Inside, the two walls surrounding the visitor reflect the parallelism through their corresponding shapes (though I found it admittedly difficult to focus on this relationship since the walls are set a bit too far apart and my attention was drawn to either one respectively—this might be an analogy to the aural perception of a musician performing the piece). Viewed from outside, meanwhile, the offset parallelism between the rows mirrors the staggered fugal entries and adds a perceivable dynamism to the steel sculpture, by accentuating relationships along a slightly diagonal axis.

[7.3] The 45-degree angle in the arrangement from front to back, meanwhile, arises from pitch being represented both in the height of the metal bars and in the distance between the rows, as Neugeboren explained. He also acknowledged, however, that the mapping of pitch to physical height is counterintuitive. While the sculpture’s evocation of organ pipes might honor Bach as a virtuoso performer on that instrument, the mechanical logic of this allusion is in fact inverted: rather than the tallest bars corresponding to the lowest pitches, in the sculpture, the bass is represented by the shortest bars in the front row. As such, the sculpture displays the conceptual metaphor of “pitch height” in material monumentality, while at once highlighting its clash with acoustics.(71) Neugeboren reflected on this tension:

It has a disadvantage in the depicted version: the high frequency of soprano tones is represented on the respective plane through its corresponding spatial height. The towering monumentality of this high range oppresses the bass, the “foundational force of the bass.” [It is] incidentally a deficiency that could easily be overcome. (1929, 16–19)(72)

Yet, to the artist, this “deficiency” was outweighed by the way in which the height of the metal bars signifies the distance of each tone from their common foundation—both literally, and figuratively as the distance from the tonic.(73) In practice, this referential value of the tonic remains symbolic, since the final tonic

[7.4] As such, Neugeboren’s “Hommage à J. S. Bach” might even come to reconcile the ideological opposition that surrounded the reception of Bach’s music in early twentieth-century Germany. The material display shows that a modernist adaptation of Bach’s polyphony does not necessarily negate its foundation in functional tonality. After all, also Krenek, Busoni, Bekker, Mersmann, and other forward-looking composers and critics who appealed to Bach’s music as a model for new stylistic pathways did not deny the historically situated harmonic language of the eighteenth century. The comparison to Klee’s rendition has shown, moreover, that the choice of a chromatic, rather than a diatonic, framework entails certain representational affordances. In the case of Neugeboren’s sculpture, this artistic decision bestows identical shapes to the three voices participating in the stretto of Example 10 and thereby brings out the correlation of their internal intervallic relations and their parallelism with one another.

Conclusion—Reaching out

[8.1] This is but one of the insights that viewers might take away from a visit to “Hommage à J. S. Bach.” The graphs and the sculpture discussed above, by Neugeboren and by Klee, moreover invite their spectators to listen to Bach’s music in a linear way, focusing on the horizontal trajectories of the individual contrapuntal voices. By hypostatizing this hearing in a materially stable form, they open its various epistemic layers to new modes of inspection. They bring out the ways in which music analysis prioritizes certain elements of the musical texture over others: emphasizing the linear dimension of polyphony inevitably obscures the perception of other parameters, such as harmony. Thereby, these visual renditions demonstrate the limitations of such a hearing that Halm worried about in his critique of Busoni’s conception of “reckless polyphony” and that Kurth’s critics deplored. At the same time, when the idea of appreciating polyphonic music as a “paralinear texture”—as advocated by Busoni and Kurth—is translated into the visual realm, this operation exposes the cognitive processes that such a hearing relies on: the ability to perceive individual melodic strands as unified entities, as explored in the pioneering research of Gestalt psychology.

[8.2] While the artistic renditions of Neugeboren and Klee are very much of their time, embedded in the debates around musical linearity and the reception of Bach’s music in 1920s Germany, they catapult this cultural context into the present. After all, as Neugeboren pointed out, one of the achievements of his sculpture is to capture Bach’s polyphony (and genius) through a lasting manifestation, which would overcome music’s dependency on performance for being brought to life and, even then, its inherent ephemerality.(74) By extension, “Hommage à J. S. Bach” casts an unfading tribute also to a linear understanding of counterpoint—the objectification of a way of interpreting fugues that was so prevalent in early twentieth-century culture and much beyond.

[8.3] Many of these contextual facets lie latent in the artifacts, however, and come to the fore only by considering the objects in dialogue with music-theoretical, artistic, and scientific concerns of the time. While these contemplations might well take place in a closed study or archival reading room, the sculpture projects these narratives into the public sphere. As an openly accessible monument, “Hommage à J. S. Bach” invites everyone in. To music scholars, this provides a unique and rich opportunity to extend the impact of their profession to new audiences. If we channel the pedagogical impetus that is already inherent in the artistic renditions discussed above, we might be able to expand the “sharability” that Lochhead (2006, 68) ascribed to intermedial translations of music. With Neugeboren’s sculpture, for instance, the comprehension that it captures of the underlying music is locked behind its various conceptual layers. In other words, “seeing” the sculpture in Examples 1, 8, and 9 does not automatically translate into “seeing” an excerpt from a Bachian fugue in it, let alone comprehending it in any particular way, or perceiving it with the multitude of senses it might allow for. Here, music theorists can facilitate a multi-sensory encounter with the monument and its referents, by guiding visitors towards its audible dimension through the music that it represents and further towards the sculpture’s theoretical and cultural significance. When understood to embody music-theoretical knowledge, artifacts such as graphical representations or sculptures can lend themselves to initiatives of communicating disciplinary concerns—approaches, methods, debates, histories—to the wider public.(75) Engaging the monument not just as a “musical object,” as Lochhead (2006) conceived of similar translations, but also as a “music-theoretical object,” in turn, rewards us with ways of making analytical concepts audible, visible, and even tangible.

Stephanie Probst

University of Cologne

Faculty of Human Sciences

Gronewaldstrasse 2

50931 Cologne

Germany

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1767-9200

steprobst@uni-potsdam.de

Works Cited

Adorno, Theodor W., and Ernst Krenek. 1974. Theodor W. Adorno und Ernst Krenek: Briefwechsel. ed. Wolfgang Rogge. Suhrkamp.

Albright, Daniel. 2000. Untwisting the Serpent: Modernism in Music, Literature, and Other Arts. University of Chicago Press.

—————. 2014. Panaesthetics: On the Unity and Diversity of the Arts. Anthony Hecht Lectures in the Humanities. Yale University Press.

Anonymous. 1985. “Bach-Denkmal eines Kronstädters in Leverkusen: ‘Der zeitliche und räumliche Verlauf von Musik

Ash, Mitchell G. 1995. Gestalt Psychology in German Culture, 1890–1967: Holism and the Quest for Objectivity. Cambridge University Press.

Auerbach, Brent. 2017. “Nonmusical Performances of Bach’s Music as Acts of Critical Analysis.” Paper presented at “Bach in the Age of Modernism, Postmodernism, and Globalization,” University of Massachusetts, Amherst, April 22.

Bekker, Paul. 1918. “Kontrapunkt und Neuzeit.” Frankfurter Zeitung, March 27, 1918.

Bonnefoit, Régine. 2008. “Paul Klee und die ‘Kunst des Sichtbarmachens’ von Musik.” Archiv für Musikwissenschaft 65 (2): 121–51.

Bonnefoit, Régine. 2009. Die Linientheorien von Paul Klee. Michael Imhof.

Busoni, Ferruccio, ed. 1894. The Well-Tempered Clavichord [Book 1] by Johann Sebastian Bach: Revised, Annotated, and Provided with Parallel Examples and Suggestions for the Study of Modern Pianoforte-Technique. Schirmer.

—————. 1921. “Selbst-Rezension (1912).” Musikblätter des Anbruch 3 (January): 22–24.

Daston, Lorraine, and Peter Galison. 2007. Objectivity. Zone Books.

De Bruyn, Eric C.H. 2014. “Beyond the Line, or a Political Geometry of Contemporary Art.” Grey Room 57: 24–49. https://doi.org/10.1162/GREY_a_00154.

Diesterweg, Adolf. 1926. “Berliner Musik.” Zeitschrift für Musik 93 (4): 220–22.

Dietzsch, Folke F. 1991. “Die Studierenden am Bauhaus: Eine analytische Betrachtung zur strukturellen Zusammensetzung der Studierenden, zu ihrem Studium und Leben am Bauhaus sowie zu ihrem späteren Wirken.” PhD diss., Weimar: Hochschule für Architektur und Bauwesen.

Dudek, Peter. 2017. “Sie sind und bleiben eben der alte abstrakte Ideologe!”: der Reformpädagoge Gustav Wyneken (1875–1964): eine Biographie. Verlag Julius Klinkhardt.

Duparcq, J.J. 1970. “Das Joh. Seb. Bach-Denkmal des Kronstädters Heinrich Neugeboren in Leverkusen.” Siebenbürgische Zeitung, September 15, 1970.

Ehrenfels, Christian. [1890] 1988. “On ‘Gestalt Qualities.’” In Foundations of Gestalt Theory, ed. and trans. Barry Smith, 82–116. Philosophia Verlag. Originally published as “Über ‘Gestaltqualitäten.’” Vierteljahrsschrift für wissenschaftliche Philosophie 14 (1890): 249–92.

Fontaine, Susanne. 2000. “Ausdruck und Konstruktion: Die Bachrezeption von Kandinsky, Itten, Klee und Feininger.” In Bach und die Nachwelt, ed. Michael Heinemann and Joachim Lüdtke, 3: 1900–1950, 396–426. Laaber.

Friedland, Martin. 1922. “Die ‘Neue Musik’ und ihr Apologet: Gedanken eines fortschrittlichen Reaktionärs zum ‘Düsseldorfer Tonkünstlerfest.’” Neue Zeitschrift für Musik 89 (15–16): 334–8.

Fux, Johann Joseph. Gradus ad Parnassum, sive manuductio ad compositionem musicae regularem, methodo novâ ac certâ, nondum antè tam exacto ordine in lucem edita. Vienna, 1725.

Graeser, Wolfgang. 1924. “Bachs ‘Kunst der Fuge.’” Bach-Jahrbuch 21: 1–104.

Halm, August. 1921. “Über Ferruccio Busoni’s Bachausgabe.” Melos 2 (10, 11–12): 207–13, 239–44.

Heuß, Alfred. 1923. “Das 53. Tonkünstlerfest des Allgemeinen deutschen Musikvereins in Kassel vom 8. bis 13. Juni.” Zeitschrift für Musik 90 (13–14): 277–82.

Hilewicz, Orit. 2017. “Listening to Ekphrastic Musical Compositions.” PhD diss., Columbia University.

—————. 2018. “Reciprocal Interpretations of Music and Painting: Representation Types in Schuller, Tan, and Davies after Paul Klee.” Music Theory Online 24 (3). https://doi.org/10.30535/mto.24.3.3.

Hinrichsen, Hans-Joachim. 2000. “Motorik, Organik, Linearität: Bach im Diskurs der Musiktheoretiker.” In Bach und die Nachwelt, ed. Michael Heinemann and Joachim Lüdtke, 3: 1900–1950: 337–78. Laaber.

Hyer, Brian. 1995. “Reimag(in)Ing Riemann.” Journal of Music Theory 39 (1): 101–38. https://doi.org/10.2307/843900.

Jenkins, J. Daniel. 2017. “Towards a Curriculum in Public Music Theory.” Engaging Students: Essays in Music Pedagogy, vol. 5. https://doi.org/10.18061/es.v5i0.7243.

Kampe, Gordon. 2014. “‘Misreading’ Ernst Kurth—Der Einfluss der Schriften Ernst Kurths auf zeitgenössische Autoren.” In Musikalische Logik und musikalischer Zusammenhang: vierzehn Beiträge zur Musiktheorie und ästhetik im 19. Jahrhundert, ed. Patrick Boenke and Birger Petersen-Mikkelsen, 213–22. Georg Olms Verlag.

Kandinsky, Wassily. 1926. Punkt und Linie zu Fläche: Beitrag zur Analyse der malerischen Elemente. Bauhausbücher 9. Albert Langen.

—————. 1947. Point and Line to Plane: Contribution to the Analysis of the Pictorial Elements. Translated by Hilla Rebay and Howard Dearstyne. Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation.

Kim, Youn. 2003. “Theories of Musical Hearing, 1863–1931: Helmholtz, Stumpf, Riemann and Kurth in Historical Context.” PhD diss., Columbia University.

Klee, Paul. 1925. Pädagogisches Skizzenbuch. Bauhausbücher 2. Albert Langen.

Knorr, Iwan. 1912. Die Fugen des “Wohltemperierten Klaviers” von Joh. Seb. Bach in bildlicher Darstellung. Breitkopf & Härtel.

Krebs, Wolfgang. 1998. Innere Dynamik und Energetik in Ernst Kurths Musiktheorie: Voraussetzungen, Grundzüge, analytische Perspektiven. H. Schneider.

Kurth, Ernst. 1913. Die Voraussetzungen der theoretischen Harmonik und der tonalen Darstellungssysteme. Drechsel.

—————. 1922. Grundlagen des linearen Kontrapunkts: Bachs melodische Polyphonie. 2 rev. Max Hesse.

—————. 1931. Musikpsychologie. Hesse.

La Motte-Haber, Helga de. 1986. “Die Musikpsychologie von Ernst Kurth.” Schweizer Jahrbuch für Musikwissenschaft 6–7: 95–108.

Lochhead, Judy. 2006. “Visualizing the Musical Object.” In Postphenomenology: A Critical Companion to Ihde, ed. Evan Selinger, 67–86. State University of New York Press.

Louis, Rudolf. 1893. Der Widerspruch in der Musik. Bausteine zu einer ästhetik der Tonkunst auf realdialektischer Grundlage. Breitkopf & Härtel.

—————. 1909. Die deutsche Musik der Gegenwart. G. Müller

Marvin, Elizabeth West. 1987. “Tonpsychologie and Musikpsychologie: Historical Perspectives on the Study of Music Perception.” Theoria 2: 59–84.

Maur, Karin von. 1998. “Feininger und die Kunst der Fuge.” In Musikwissenschaft zwischen Kunst, ästhetik und Experiment: Festschrift Helga de la Motte-Haber zum 60. Geburtstag, ed. Reinhard Kopiez, 343–58. Königshausen & Neumann.

Mersmann, Hans. 1920. “Die Sonate für Violine allein v. Artur Schnabel.” Melos 1 (18): 406–18.

Metzger, Christoph. 1998. “Die künstlerische Bach-Rezeption bei Paul Klee und Lyonel Feininger.” In Musikwissenschaft zwischen Kunst, Ästhetik und Experiment: Festschrift Helga de la Motte-Haber zum 60. Geburtstag, ed. Reinhard Kopiez, 371–85. Königshausen & Neumann.

Neugeboren, Henrik. 1929. “Eine Bach-Fuge im Bild.” bauhaus: vierteljahr-zeitschrift für gestaltung 3 (1): 16–19.

Ott, Günther. 2003. “Neugeboren Unbekannt? - Mitnichten!” Siebenbürgische Zeitung, July 15, 2003.

Paterson, Mark. 2007. The Senses of Touch: Haptics, Affects and Technologies. Berg.

Poos, Heinrich. 1998. “Henrik Neugeborens Entwurf zu einem Bach-Monument (1928). Dokumentation und Kritik.” In Töne, Farben, Formen: Über Musik Und Die Bildenden Künste, ed. Elisabeth Schmierer, Susanne Fontaine, Werner Grünzweig, and Matthias Brzoska, 2nd rev., 45–57. Laaber Verlag.

Probst, Stephanie. 2018. “Sounding Lines: New Approaches to Melody in 1920s Musical Thought.” PhD diss., Harvard University.

Rehding, Alexander. 1995. “(Mis)Interpreting Ernst Kurth.” MA thesis, Cambridge University.

Riemann, Hugo. 1914–15. “Ideen zu einer ‘Lehre von den Tonvorstellungen.’” Jahrbuch der Musikbibliothek Peters 21/22: 1–26.

Rothfarb, Lee Allen. 1988. Ernst Kurth as Theorist and Analyst. University of Pennsylvania Press. https://doi.org/10.9783/9781512806267.

—————. 1991. Ernst Kurth: Selected Writings. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511470288.

Schader, Luitgard. 2001. Ernst Kurths “Grundlagen des linearen Kontrapunkts”: Ursprung und Wirkung eines musikpsychologischen Standardwerkes. J.B. Metzler. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-476-02780-1.

Schillinger, Joseph. 1946. The Schillinger System of Musical Composition. C. Fischer. https://doi.org/10.2307/3400410.

Schmid, Nora, and Lea Hinden, eds. 2007. “Volltextbriefe zum Inventar Nachlass Ernst Kurth (Vers. 4.0).” University of Bern, Institut für Musikwissenschaft. http://www.musik.unibe.ch/dienstleistungen/nachlass_kurth/index_ger.html.

Shephard, Tim and Anne Leonard, eds. 2013. The Routledge Companion to Music and Visual Culture. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203629987.

Tan, Daphne. 2013. “Ernst Kurth at the Boundary of Music Theory and Psychology.” PhD diss., Eastman School of Music, University of Rochester.

—————. 2015. “Beyond Energetics: Gestalt Psychology in Ernst Kurth’s ‘Musikpsychologie.’” Theoria 22: 99–129.

Tunnicliffe, Stephen. 2000. “Wolfgang Graeser (1906–28): A Forgotten Genius.” Musical Times 141 (1870): 42–44. https://doi.org/10.2307/1004368.

Vergo, Peter. 2010. The Music of Painting: Music, Modernism and the Visual Arts from the Romantics to John Cage. Phaidon.

—————. 2011. “How to Paint a Fugue.” In Music and Modernism, ca. 1849–1950, ed. Charlotte De Mille, 8–23. Cambridge Scholars.

Vitali, Christoph, ed. 1986. Paul Klee und die Musik: Schirn-Kusthalle Frankfurt, 14. Juni bis 17. August 1986. Nicolaische Verlagsbuchhandlung.

Watkins, Holly. 2011. Metaphors of Depth in German Musical Thought: From E. T. A. Hoffmann to Arnold Schoenberg. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511820496.

Werker, Wilhelm. 1922. Studien über die Symmetrie im Bau der Fugen und die motivische Zusammengehörigkeit der Präludien und Fugen des “Wohltemperierten Klaviers” von Johann Sebastian Bach. Breitkopf and Härtel.

Wertheimer, Max. 1922. “Untersuchungen zur Lehre von der Gestalt.” Psychologische Forschung: Zeitschrift für Psychologie und ihre Grenzwissenschaften 1: 47–58. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00410385.

—————. 1923. “Untersuchungen zur Lehre von der Gestalt. II.” Psychologische Forschung: Zeitschrift für Psychologie und ihre Grenzwissenschaften 4: 301–50. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00410640.

Zbikowski, Lawrence. 2002. Conceptualizing Music: Cognitive Structure, Theory, and Analysis. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195140231.001.0001.

Art Works and Graphs

Art Works and Graphs

Klee, Paul. 1922. Beiträge zur bildnerischen Formlehre. Manuscripts “Bildnerische Form- und Gestaltungslehre.” Zentrum Paul Klee, Bern. https://www.zpk.org/de/sammlung-forschung/sammlung-archiv/paul-klee-bildnerische-form-und-gestaltungslehre-389.html.

—————. 1938. Heroische Bogenstriche (Heroic Strokes of the Bow). Pigmented paste on newspaper on dyed cloth on board in artist’s frame, 28 3/4 x 20 7/8" (73 x 53 cm). MoMA, New York City. https://www.moma.org/s/ge/collection_ge/object/object_objid-38349.html.

Neugeboren, Henrik. 1944. Grafische Darstellung einer Fuge von Johann Sebastian Bach (“Fuge à 4 / Wohltemp. Klav. No. 1”). Red and black ink over pencil on graphing paper, 30 x 112 cm. Bauhaus Archive, Berlin (5643).

Neugeboren, Henrik, J.J. Duparcq, and Cornelis Hoogenboom. 1928/1966/1967–68. Hommage à J.S. Bach. Stainless steel sculpture, ca. 7m high.

Neugeboren, Henrik, Gerda Marx, and J.J. Duparcq. 1928/1944/1966. Plastische Darstellung einer Fuge von Johann Sebastian Bach (Es-Moll-Fuge, BWV 853, Takte 52 bis 55). Stainless steel sheets on wooden basis (maquette), 79,8 x 79,8 x 76 cm. Bauhaus Archive, Berlin (F6334).

Footnotes

* Among many who have helped shape this article through encouraging discussions and engaged feedback, I would like to thank Richard Beaudoin, Leon Chisholm, Alexander Rehding, Daphne Tan, David Trippett, and the anonymous reviewers of this journal. Earlier versions of this article, which derives from a chapter of my Ph.D. dissertation and a presentation at the AMS annual meeting in Vancouver in 2016, benefitted especially from productive criticism by Suzannah Clark, Hayley Fenn, and Cécile Guédon.

Return to text

1. In the manuscript, the fugue is notated in D-sharp minor (but the prelude in E-flat minor). Editions differ on the keys in which the two movements are notated. As we shall see, enharmonic equivalence was central to Neugeboren’s conceptualization of music.

Return to text

2. In the Siebenbürgische Zeitung (issue of September 15, 1970, 3), the French musicologist J. J. Duparcq argues that Neugeboren had drafted the sketch of Bach’s Fugue already in 1924 and was encouraged by a friend to visit the Bauhaus in order to have it prepared for realization. He also reports that the initiative for the monument came from Neugeboren’s last partner Hedwige Nadolny (1886–1975), who entrusted the sketches of the sculpture to the city of Leverkusen and assented to its realization. This information is reproduced in an article in the same newspaper from September 15, 1985, 7. The hospital is in the immediate vicinity of the Museum Schloss Moirsbroch, a venue for exhibitions of contemporary art that had acquired and showed some of Neugeboren’s work in the past. On a later exhibition honoring the Transylvanian artist, see also https://www.siebenbuerger.de/zeitung/artikel/alteartikel/2252-neugeboren-unbekannt-mitnichten.html.

Return to text

3. “Ob solche darstellung nicht eine würdigere art von bach-monument wäre als die bekannten kitschigen postamentfiguren mit notenrollen.” In the manner typical of the Bauhaus, the entire text is printed in lowercase letters. Throughout, all translations are my own, unless otherwise noted.

Return to text

4. “diese zeichen bachscher kombinationsgröße.”

Return to text

5. Bolstering the idea that such renditions capture a specific way of hearing the music, Brent Auerbach (2017) has suggested the designation “non-sonic performances.”

Return to text

6. Orit Hilewicz (2017, 2018) has convincingly described the ways in which the reciprocal interpretation of music and painting in examples of musical ekphrasis can enrich the perception of both. For a general overview of methodological concerns with respect to the intersection between music and the visual arts, see Shephard and Leonard 2013.

Return to text

7. In the literature on comparative arts, especially in the cultural context of Modernism, Albright’s work (esp. 2000, 2014) offers a comprehensive account of the myriad possible relationships between different art forms.

Return to text