Generic Norms, Irony, and Authenticity in the AABA Songs of the Rolling Stones, 1963–1971

David S. Carter

KEYWORDS: The Rolling Stones, AABA form, Formenlehre, rock music, genre, soul, irony, authenticity

ABSTRACT: AABA form was in decline in popular music in the 1960s, yet the Rolling Stones made extensive use of it at a crucial point in their career. In this article I examine the relationship between Jagger-Richards AABA songs released between 1963 and 1971 and established AABA norms. I use a corpus of 138 AABA songs (112 by other artists and 26 by Jagger-Richards) to compare the Stones’ approach to elements such as starting and ending bridge harmonies and verse melodic form with existing defaults. The analysis shows that the band’s approach to AABA in this time period bifurcates into two strategies, each associated with a tempo extreme: either (1) using the form ironically to critique wealth and privilege, or (2) employing it in a sincere way that invokes soul and gospel artists and thereby claims authenticity for the band.

DOI: 10.30535/mto.27.4.1

Copyright © 2021 Society for Music Theory

1. Introduction

[1.1] Mick Jagger and Keith Richards have described their 1966 hit “Mother’s Little Helper” in terms not usually associated with the Rolling Stones: “quite vaudeville in a way,” said Richards (di Perna 2002), and “like a music hall number,” said Jagger (Loewenstein and Dodd 2003, 100.) One likely reason for these descriptions is the song’s use of AABA, a form associated more with the professional songwriters of Tin Pan Alley than with the so-called “Greatest Rock ’n’ Roll Band in the World” (McCormick 2012). While the early Stones are usually linked to the blues and R&B, at a critical juncture in their career they surprisingly embraced a pop-song form with sentimental, nostalgic associations and used it in two ways: either as an ironic tool to critique bourgeois pretensions, or as a vehicle for the band to achieve soulful authenticity. They turned toward AABA at a time when this form was statistically in decline in popular music, and their use of it coincided with a sudden increase in their original song output and with decreased reliance on 12-bar blues progressions.

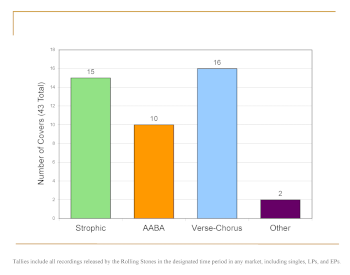

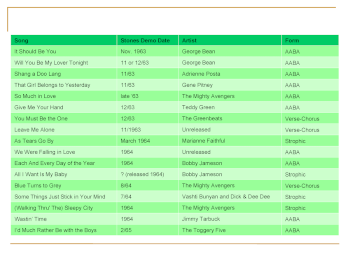

Example 1. Stones covers formal types, 1963–65

(click to enlarge)

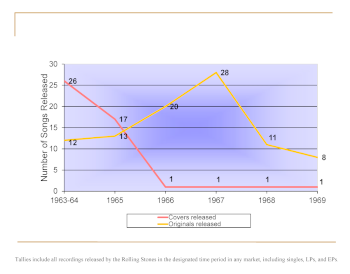

[1.2] Early on, the Rolling Stones were primarily an R&B and blues cover band. They styled themselves in their early publicity as “A Shot of Rhythm and Blues: The Real Thing.” With but a few exceptions, they exclusively covered Black American artists (Karnbach and Benson 1997, 56, 59). As Example 1 shows, the songs that the Stones covered between 1963 and 1965 primarily used strophic and verse-chorus forms, and twelve-bar blues progressions were frequent. There was a constant push-and-pull in the Stones’ first two years as recording artists between their desire for R&B and blues “authenticity” and producer Andrew Loog Oldham’s encouragement of greater commerciality (Oldham 2000, 267). Starting with their first album in 1964, the Stones included a few originals among the covers. Example 2 shows how the percentage of original songs written by Jagger-Richards or by the band gradually increased through 1966, a year in which they released 20 originals and just one cover. In their original songs prior to 1966, the Stones primarily stuck to approaches consistent with their desire to be heard as “pure” R&B artists (Richards and Fox 2010, 104, 145–46; Cott 1968). They used 12-bar blues progressions in most of these songs (seven out of twelve) while avoiding AABA form in favor of strophic or verse-chorus forms (see Example 3). Of the 25 original songs the Stones released prior to 1966, the only one in AABA form or even to include a bridge was “Congratulations” (1964). At the same time that they sought R&B authenticity with their band, however, between 1963 and 1965 Jagger and Richards wrote numerous AABA songs in a more commercial vein for other artists to record. With these songs they sought financial and creative success as a songwriting team in the mold of the Brill Building writers and Lennon-McCartney.

Example 2. Stones covers and originals by year, 1963–1969 (click to enlarge) | Example 3. Stones form usage in their original songs by year, 1963–1971 (click to enlarge) |

[1.3] In recording sessions in December of 1965, Jagger and Richards increasingly incorporated AABA form into their songs for the Stones as well. While the Stones prior to 1966 had released only one original song that used AABA, in 1966 alone seven of their 20 original releases used the form (35% in Example 3); most of these appeared on the LP Aftermath. Their turn to AABA in 1966 coincided with their giving up covers in favor of recording almost exclusively original songs and discontinuing their writing of songs for other artists. Jagger and Richards thus integrated their previously separate identities as songwriters for others and as the leaders of the cover band the Rolling Stones, ostensibly providing them with authenticity as creative artists. Their focus on AABA continued into early 1967 and the Between the Buttons LP, such that five of their 14 originals released prior to June of that year used the form. Formally, these songs recalled the AABA traditions of Tin Pan Alley and the Brill Building even as they reflected contemporary trends of expanding the form.

Example 4. Tempos of Stones AABAs, 1964–1971

(click to enlarge)

[1.4] While moderate and moderately slow tempos were very much the norm for AABA songs in the 1960s by other artists, the Stones’ AABAs tended towards either great speed or great deliberateness. These tempo categories are associated with two divergent lyrical and musical approaches. Example 4 shows that most of the Stones’ AABA songs in this era (10/17) were either very fast, with tempos >150 bpm, or slow, with tempos <100 bpm. The faster songs, such as “19th Nervous Breakdown,” “Mother’s Little Helper,” and “Have You Seen Your Mother, Baby, Standing in the Shadow?”, contain scathing, ironic lyrics and fly through the AABA form, using it satirically to critique the perceived complacency and corruption of the previous generation in a way that anticipates how punk would use AABA in the seventies. The slower AABAs, on the other hand, such as “Long Long While” and “I Got the Blues,” sincerely invoke R&B, gospel, and soul ballads to achieve authenticity.

[1.5] Numerous scholars have addressed AABA form and bridges more generally in the last 20 years,(1) but a corpus analysis of the details of AABA songs has not previously been published or been used to provide context for the work of a particular artist. In the case of the Rolling Stones, there are few published scholarly musical analyses available, especially in comparison to the vast amount of detailed analysis that has been done on the music of the Beatles.(2) In addition, AABA form has usually been considered either in the context of Tin Pan Alley practice or has been analyzed as a declining form in the rock era, with few authors other than von Appen and Frei-Hauenschild (2015) and Julien (2018) making detailed connections between eras. In this article, I rely on the formal classification schemes of de Clercq (2012), Covach (2005 and 2010), Everett (2001), von Appen and Frei-Hauenschild (2015), and Nobile (2020), applying them to the AABA songs of the Rolling Stones between 1963 and 1971. I further draw on Hepokoski and Darcy’s work with sonata form (2006), undertaking a corpus analysis of selected twentieth-century AABAs (focused primarily on the 1960s) to determine the defaults for the form and how they changed over time and according to genre. Cortens (2014), Horton (2017), and Siu (2020) have demonstrated how corpus analysis data can help to reveal defaults in eighteenth- and nineteenth-century art music. Tovar (2017) and Geyer (2019) have used Hepokoski’s dialogic model to discuss defaults in popular music repertoires, with Tovar presenting examples of approaches in Broadway songs and Geyer working with a corpus consisting of the work of a single jazz artist. In this essay I apply the data-driven dialogic approaches of Cortens, Horton, and Siu to a popular music repertoire, demonstrating how data from a corpus analysis of pop songs can provide the basis for determining defaults and serve as a point of comparison for an individual artist’s work. My corpus analysis and determination of defaults, detailed in Part Two of this article, allow us to see the ways that the Rolling Stones’ AABAs either conformed or departed from those defaults and what connections their songs made with historical eras and genres.

[1.6] Following analysis in Part Three of the Jagger-Richards songs for other artists, Part Four of this article explores the expressive and social implications of the Stones’ formal choices. Musical forms, in general, connect with genres, and formal choices have expressive, dramatic, social, and political implications.(3) Formal defaults change over time, and songwriters can use older forms for dramatic or expressive purposes (Wood 2000, 68). As Rafferty has pointed out, most analyses of form in popular music have neglected the social and ideological implications of formal choices (2017, 135–40). I draw on the theory of parody to show how the Stones in many of their AABAs in this period made ironic use of the form to engage in social critique. Parody involves both repetition and critical distance from an original or set of originals (Hutcheon 1988, 26). The new work engages in a dialogue with a previous work or works; Hepokoski and Darcy emphasize that this is also the case with 18th-century sonata-form movements, whether parodic or not. (2006, 9). The original can be a single work (specific parody) or can be a body of works (general parody) (Dentith 2000, 7). Parody is a technique, rather than a genre (Dentith 2000, 19), but it brings to the foreground the formal characteristics of the works in question (Hutcheon and Woodland 2012). The most common ways of transforming the original in the parody include recontextualization (Harries 2000, 6), which is the primary method the Stones used, as well as distortion, especially exaggeration (Dentith 2000, 32), and “keying,” which sends signals to the audience to convey tone (Hymes 1974, 62). The object of criticism can be the original work(s) of art, but can also be something else, often something contemporary to the parodist (Dentith 2000, 9, 18). In the Stones’ case, the object of criticism was not just the music of Tin Pan Alley and its descendants, but also the older generation of people living in the mid-1960s who still embraced that music.

[1.7] In Part Five of this article I discuss how the Rolling Stones in other AABA songs from this period took a sincere approach to the form in a bid for authenticity. Authenticity is not a trait that inheres in a performance or recording; instead, it is a quality that is ascribed to it. It is a relative concept that is usually applied as if it were absolute (Moore 2002, 210). Moore’s “first person authenticity” denotes having ascribed integrity to oneself, with the performer ostensibly engaging in direct unmediated expression to the audience (2002, 214). Jagger and Richards’s turn towards writing original songs for the band represented an attempt to achieve authenticity of this sort. Another type classified by Moore is “third person authenticity,” which comes from the performer connecting with another group or individual believed to be more authentic (2002, 215). White musicians (problematically) believed they could channel the pain of Black musicians by performing blues or rhythm and blues (Moore 2002, 215). In doing so, they hoped to make music that was not just entertainment, but also something that could change someone’s life or heal emotional pain. The Stones’ decisions to cover almost exclusively Black artists early in their career and to imitate Black styles in their original songs allowed them to be “authentic” in this sense.

2. AABA Norms and Stones AABAs

Example 5. AABAs in Annual Top 20 by year (based on Summach 2012, 188 Ex. 4.3)

(click to enlarge)

[2.1] When Jagger and Richards started writing songs together in the latter half of 1963, AABA was a conservative formal choice that had been the primary medium for the professional songwriters of Tin Pan Alley in the first half of the century. Tin Pan Alley was associated with “sophistication,” “contrivance,” “commerce,” and “convention” (Mellers 1964, 383, 387–88, 390). In its early years, AABA usually appeared as the “chorus” or “refrain” of a song that also featured one or more “sectional” verses;(4) however, between 1925 and 1950 these verses outside the AABA structure were gradually abandoned (Middleton 2003c, 514). The 32–bar AABA was a tight-knit form and was a good fit for songwriters working with music notation, with specifically eight bars on the page in each section regardless of tempo. The ASCAP-radio network battle of 1940–41 opened the door to the rise of musics outside the Tin Pan Alley AABA mainstream, and after World War II, Tin Pan Alley AABA form began a slow decline in popularity. The rise of rock ‘n’ roll in the mid-1950s—coincident with the reduced use of notation by popular songwriters—greatly hastened that decline (Hamm 1979, 388–93).(5) Verse-chorus form became increasingly common at the top of the pop charts and gradually increased its dominance from the 1950s through the 1980s and beyond (Summach 2012, 230). Even as this occurred, early rock ‘n’ roll artists at times added bridges to their usually blues-based songs to increase their “sophistication” (Middleton 1972, 152, 155), and the songwriting team of Leiber and Stoller seemingly used AABA to help increase the appeal of their songs to white listeners (von Appen and Frei-Hauenschild 2015, 55). The ascendance of the Beatles in 1963–64 coincided with a revival of AABA, as the Fab Four, inspired in part by Brill Building songwriters of the late 1950s and early 1960s, made frequent use of the form, often expanding it beyond the classic 32-bar model (Fitzgerald 1996, 41–42; Fitzgerald 1999, 39). The use of AABA form was one of the primary indicators of the influence of Tin Pan Alley on both the Brill Building songwriters and the Beatles (Scheurer 1996, 91, 94–95; Fitzgerald 1999, 39–40). Example 5 shows that after 1964 the frequency of AABA at the top of the American pop charts declined over the course of the remainder of the 1960s.(6) The form by 1967 was either the province of extremely sincere, nostalgic attempts to refer back to an earlier generation (e.g., the septuagenarian Charlie Chaplin’s 1967 hit “This Is My Song”) or treatments of the past as a source of psychedelic strangeness (as in Traffic’s “Hole in My Shoe,” Jimi Hendrix’s “Purple Haze,” and the Stones’ “We Love You”). These songs are in certain respects distant from the classic 32-bar AABA of Tin Pan Alley’s heyday, yet they reflect the ways in which the form evolved to fit the times; they connect with AABA tradition even while updating that tradition.

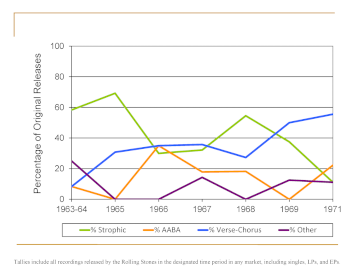

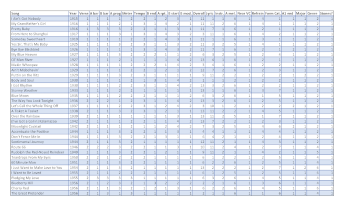

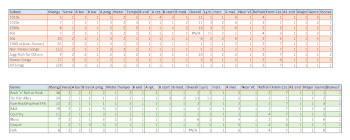

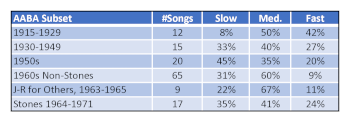

Example 6. Comparing AABA songs, 1915–1971

(click to enlarge and see the rest)

[2.2] In order to provide perspective on the Rolling Stones’ use of AABA form in the 1960s, I created a database of 138 AABA songs released between 1915 and 1971; see Example 6. Seventeen of these songs (in gold) are AABA songs written by Jagger and Richards and recorded by the Stones between 1963 and 1971; this consists of all the AABA originals that the Stones recorded from the start of their career through the 1971 Sticky Fingers album. Nine of the 138 (in green) are the AABA songs composed by Jagger and Richards between 1963 and 1965 for other artists to record. The remaining 112 AABA songs in the corpus were selected to include the most popular AABA songs of the 1960s, a smaller number of the most popular from previous decades, and a selection of representative rhythm and blues, country and western, and blues songs using the form.(7) The corpus emphasizes songs from the 1960s because the Stones AABA songs that are the focus of this study were released between 1964 and 1971. Exhaustive analysis of AABA norms in the decades prior to the 1960s is outside the scope of this paper, but earlier songs were included in the corpus in order to provide an idea of AABA practices in preceding decades.

[2.3] As shown at the bottom of Example 6, I analyzed each of the songs in the corpus according to 19 categories; 18 of these relate to the music and one classifies the lyrical content.(8) For each category, I listed the most common options and assigned a classification number to each option. In analyzing the harmonic progressions in AABA verses, I used von Appen and Frei-Hauenschild’s classification of A section progressions (2015, 20–23, 30–36, 56–57):

- wandering

- loop

- chord scheme

- R&B line

- “zero level”

For A section melodic analysis, I used classifications summarized by Nobile (2020, 39–59) along with aaab:(9)

- period or double period

- Everett’s Statement-Restatement-Departure-Conclusion (SRDC) (2001, 132), though restricted to aabc for purposes of this category

- aaba

- 12-bar blues aab or abc or variant

- aaab

- other

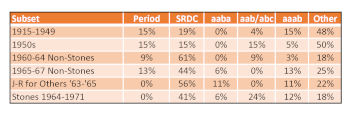

Example 7. AABA song modes by category

(click to enlarge)

The bottom of Example 6 shows details of the classifications within each of the 19 analytical categories. Example 7 indicates the most common options (modes) for each category with respect to time frame and genre, as well as for the 17 Stones songs and the nine Jagger-Richards songs for other artists. These provide a sense of the first-level defaults at different time periods and in different genres. I also determined the percentage of songs within specific time frames and genres that used particular options, allowing a clearer picture of how the popularity of compositional choices changed over time and according to genre. The results shown in Example 7 are less definitive for songs between 1915 and 1949 because of the smaller number of songs included from these decades, but nevertheless convey some idea of how practices in the fifties and sixties differed from those of earlier decades.

[2.4] Example 7 identifies the first-level defaults for the 65 AABA songs in the database released in the sixties by non-Jagger-Richards artists, along with the most common choices in Jagger-Richards AABA songs. Of particular note regarding the non-Stones group of 1960s songs:

- AABA was the most common overall form, with no additional repetitions of the A or B sections and no instrumental break.

- The most common A verse was substantially more than eight bars (most commonly 16), while the bridge was most commonly exactly eight bars.

- A chord scheme was most commonly used in the verses in combination with an SRDC melodic construction and a tail refrain.

- The bridge typically began on a diatonic predominant, lacked a modulation or a lengthy harmonic sequence, and concluded on the dominant.

- Straight (no-swing) 4/4 was typically used at a moderate tempo.

- The lyrics most commonly related to lost love or otherwise troubled romance.

- Instrumental breaks were less common than they had been in previous decades.

In addition to AABA, AABA BA was also a common choice as overall form in the 1960s, particularly in the 1965–67 period. The use of 16-bar (or sometimes 18-bar) A sections was a major change from prior decades, as the eight-bar verse was the norm in the Tin Pan Alley era through the 1950s. Example 11, below, shows that SRDC was the normative structure in A sections in the 1960s (particularly in the first half of the decade), having been used much less frequently prior to then (Summach 2011 [14]). The rise of SRDC was related to the ascendance of the 16-bar A section, as the expanded size of these verses allowed for clear subdivision into four phrases, each four bars in length. Another major difference from prior decades was the preference in the 1960s for a straight rather than swung or shuffled 4/4, as the latter had been the norm in AABAs through the 1950s.

[2.5] The Stones’ AABAs followed prevailing 1960s trends in certain respects but bucked them in others. Review of the corpus shows an increasingly loose approach to overall form in popular music as a whole as the 20th century progressed.(10) AABA form in the teens and 1920s was treated as a single unit—the sectional chorus after a sectional verse—that was repeated and from which the sections could not be separated. Gradually, however, the form came to be treated as a collection of detachable and exchangeable modules: verses (A sections) and bridges (B sections). The Beatles’ “broken AABA forms” discussed by Covach (2006, 43–45) can be seen as part of a wider and gradual historical trend among songwriters to conceive of individual sections within an AABA song as discrete and rearrangeable units. An AABA BA arrangement is a simpler, more common example of the way in which the AABA unit was fragmented, and this arrangement of sections became a second-level default in the early 1960s. It became even more common for artists in AABA songs in the 1960s to dispense with repetition of the bridge altogether, often resulting in a simple AABA form for the song as whole. But the Stones generally continued to repeat the bridge in their AABA songs, even in instances in which the number of bars in their A and B sections was substantially more than the prototypical eight. The Stones tended to favor slight variations on AABA BA in their AABA songs; examples include “Long Long While” (AABA BA AA), “Stupid Girl” (AABA Instr.(B)A), as well as “All Sold Out” and “Sway” (both AAB Instr.(A)BA).(11) By comparison, other artists in the 1960s generally made use of the basic AABA BA form (such as in the Beatles’ “Yesterday” or Elvis’s “Stuck on You”) or dispensed with the repeat of the bridge for an overall AABA.

Example 8. Percentage of AABA songs with given A section lengths in measures

(click to enlarge)

Example 9. Average tempo scores for section lengths

(click to enlarge)

[2.6] It is also possible to compare the Stones’ approach to individual A and B sections with historical practice and 1960s norms. Just as there was a loosening of the overall organization of AABA songs between 1915 and 1965, there was a loosening of the confines of individual verses and bridges within AABA modules. The commonplace expansion of the A section past eight bars (often to 16) in the 1960s was part of a general trend away from the hypermetric regularity of the strict 32-bar structure of Tin Pan Alley.(12) In the 1960s we see some songs like the Beatles’ “Yesterday” having a seven-bar A section, some doubling the eight bars to 16 or more, and others like Elvis Presley’s “Crying in the Chapel” exhibiting the normal eight-bar A section but with a B section that is only half as long.(13) The Rolling Stones largely followed the trend towards expansion and greater irregularity in the length of A sections in AABA songs. After 1964’s “Congratulations,” the Stones had only one AABA song with an eight-bar A section up through 1971; this was 1968’s “Salt of the Earth.” As Example 8 shows, the band’s AABAs in the mid- and late 1960s were even more likely to have longer, more irregular A sections than the prevailing taste at the top of the charts. Even in the songs Jagger and Richards wrote for other artists in 1963–64, their standard approach was to include 16 bars in the A section rather than eight. Yet while we see eight-bar A sections in very prominent AABAs in the mid- and later 1960s, such as in the Beatles’ “We Can Work It Out,” the Box Tops’ “The Letter,” and Frank Sinatra’s “Strangers in the Night,” not a single Stones AABA song from the years in which they most focused on the form—1966 and 1967—has an eight-bar A section. In some cases, their deviation from the eight-bar norm resulted in hypermetric irregularity, as in “All Sold Out” (nine-bar verse), while in others the Stones used an even 16 bars.(14) A contributing factor to the Stones' tendency towards longer A sections (in terms of number of measures) was their use of extremely fast tempos in some AABAs of this period. Example 9 shows that faster tempos correlated with more bars in a section, presumably in part because it would take more bars to cover the same amount of time as in a moderate-tempo song. The Stones, more so than other artists in the 1960s, seemed to conceive of section lengths in terms of absolute seconds rather than in terms of number of bars. As a result, there was greater variability in the lengths of their A and B sections than in songs by contemporary artists.

Example 10. Percentage of AABA songs with given harmonic approaches in the A section

(click to enlarge)

[2.7] With respect to the harmonic approaches of AABA verses, the Stones favored chord loops more than other artists. Chord loops feature a repeating chord pattern with a faster harmonic rhythm early in the verse. The first-level default for AABA verse harmonic progressions in the 1960s was the chord scheme (see Example 10). Chord schemes were associated more with country & western and the blues than with mainstream Tin Pan Alley (von Appen and Frei-Hauenschild 2015, 23), and they came to be particularly dominant in popular music beginning in the 1950s. Chord schemes, such as 12-bar-blues progressions, tend to feature a slower harmonic rhythm, especially at the start of a section, with an acceleration in harmonic rhythm as the section-ending cadence is approached. The Stones used chord schemes almost as frequently as other artists. Additionally, between 1966 and 1968 they recorded several songs incorporating passages with a slower harmonic rhythm or even harmonic stasis, for instance in the verses of “Mother’s Little Helper,” the bridge of “Have You Seen Your Mother, Baby, Standing in the Shadow?,” the guitar solo on a prolonged tonic harmony in “All Sold Out,” and in the coda of the non-AABA “Jumpin’ Jack Flash.” The Stones, however, defied contemporary AABA trends by using chord loops just as frequently as they used schemes, including in songs they wrote for other artists. In seven of their AABA songs in this time period, the verse features a loop with a characteristically faster harmonic rhythm, including in “Have You Seen Your Mother,” “All Sold Out,” and “Let’s Spend the Night Together.”(15) Loops are particularly prevalent in their 1968–1971 AABAs, among them “Salt of the Earth,” “Stray Cat Blues,” and “Sway.”

Example 11. Percentage of AABA songs using a given melodic form in the A section

(click to enlarge)

[2.8] Example 11 shows that, in six out of 17 Stones AABA songs in the study, SRDC was the most common approach to melodic form in the A section, with the band deploying it almost as frequently as other artists in 1960s AABAs. The Stones used SRDC, but they also relied on aab or abc forms associated with twelve-bar-blues progressions as well as other arrangements of the A section. SRDC reached a new peak of popularity in the early-to-mid-1960s — Everett notes that the Beatles were very fond of it (2001, 132) — and began to decline in popularity in 1966–67.(16) Notably, Jagger and Richards made significantly more frequent use of SRDC in the verses of their AABA songs for other artists, fitting with the tendency of these songs towards conventionality.

Example 12. Percentage of AABA songs with a given bridge length

(click to enlarge)

[2.9] In their bridges, the Stones favored extensions and diminutions of the standard eight-bar length, more so than other 1960s artists recording AABAs (Example 12). Expansion of the bridge substantially beyond the classic eight bars was an option that had become more common among 1960s artists, occurring in about 20% of the non-Stones songs from this period in the corpus. Yet when comparing Example 8 and Example 12, we see that, among other artists, hypermetric irregularity was more common in verses than bridges.(17) The frequency of the Stones’ use of longer bridges is 29% (five in 17), which, while comparable to the 20% figure among other artists, remains on the high side. Five Rolling Stones bridges from this time period are substantially longer than eight bars: “19th Nervous Breakdown,” “Have You Seen Your Mother,” “Mother’s Little Helper,” “Let’s Spend the Night Together,” and “We Love You.” These bridges are longer not just in number of bars but in seconds of actual time. Three Stones AABAs in the corpus have bridges substantially shorter than eight bars; these are “Long Long While,” “She Smiled Sweetly,” and “Sway” (all three are ballads). Four slightly exceed the eight-bar norm, these being “Doncha Bother Me” (10 bars), “All Sold Out” (10), “Miss Amanda Jones” (10), and “Stray Cat Blues” (10).

Example 13. Percentage of AABA songs with modulation or harmonic sequence in the bridge

(click to enlarge)

Example 14. Percentage of AABA songs with given harmonies at the end of the bridge

(click to enlarge)

[2.10] Tin Pan Alley bridges frequently made use of two harmonic conventions: (1) modulation and/or a significant harmonic sequence (Example 13), and (2) ending the bridge on the dominant, which was an overwhelmingly common first-level default (Example 14). By the 1960s, bridges no longer typically included a modulation or substantial chromaticism, but ending the bridge on the dominant was still the norm. While the Stones followed prevailing fashion in mostly avoiding substantial bridge chromaticism, their AABAs were much more likely than those of other 1960s artists to conclude bridges on something other than the dominant. The overwhelming majority (78%) of AABA songs by others in the 1960s end their bridges on the dominant, but only 10 of the Stones’ 17 AABAs in the study do so (59%). Ending the bridge on tonic was more common among other 1960s artists than it had been in prior decades,(18) but it still remained relatively rare (occurring in 16% of 1965-67 AABAs). The Stones, however, showed a somewhat greater predilection in their AABAs for ending the bridge on tonic, with the bridges of four of their 17 AABAs in the period doing so (“19th Nervous Breakdown,” “Doncha Bother Me,” “Mother’s Little Helper,” and “I Am Waiting”). In such an instance, resolution of bridge tension occurs not with the return of the A, but rather before the return. This creates a disjunction between the melodic and textural structure of a song and its harmonic structure. In the traditional AABA, the B section provides melodic, harmonic, and lyrical contrast, and the return to tonic with the return of the A simultaneously resolves these structural tensions. On occasions where the resolution back to the tonic occurs before the end of the bridge, though, we get a more complex effect, such that the structural resolutions are staggered and there is less tonal contrast between the bridge and the rest of the song. Three other Stones AABAs situated chronologically later in the period end on something other than tonic or dominant. In “We Love You” (1967), the bridge concludes on the new tonic of B minor rather than the original A tonic of A minor. In “Sway” (1971), the bridge concludes on the subdominant as a way of leading into the V–IV alternation of the guitar solo, which is based on the progression at the conclusion of the verses. And in “I Got the Blues” (1971), the concluding subdominant takes the place of the traditional dominant, preparing the way for the return of the tonic via a bluesier plagal motion rather than the common-practice dominant. All three of these songs exemplify the reimagining of AABA form that was occurring in a pop music world in which that form was no longer supreme.(19)

[2.11] To summarize: while the Stones followed prevailing trends with AABA songs in certain respects, an examination of their songs reveals some significant differences with contemporaneous practice. The Stones used chord schemes and SRDC frequently in their AABAs, yet they made more use of loop progressions and aab or abc than other artists did. Consistent with 1960s AABA norms, their bridges tended towards diatonicism. Significant differences with 1960s norms include the variability of their A sections and bridges in terms of number of bars, with the Stones opting for eight-bar sections much less frequently than other artists, even as the eight-bar bridge remained the standard. With regard to overall form, the Stones tended to repeat the bridge, even as an increasing number of 1960s AABAs avoided doing so. While the Stones’ AABA bridges usually end on the dominant, they end on something other than dominant significantly more frequently than the AABA bridges of other 1960s artists. A final important difference from ‘60s norms is the Stones’ tendency to avoid moderate tempos in AABAs and to use tempo extremes of either slowness or great speed. Parts Four and Five of this essay will examine the significance of these tempo extremes and discuss other respects in which the Stones’ choices in their AABA songs interacted with norms of the 1960s and earlier. In advance of that, though, Part Three will examine more closely the earliest Jagger-Richards AABA songs.

3. Jagger-Richards Songs for Others

[3.1] To gain further perspective on the Stones’ use of AABA form in the 1960s, it is useful to look at the earliest Jagger-Richards AABAs. These were songs written not for the Stones to record, but for other artists. In composing these songs, Jagger and Richards sought to place themselves in a professional songwriting tradition centered in London’s Denmark Street, the British Tin Pan Alley. These early AABAs for others were conventional in many ways, and examining their characteristics allows us to see how the early Stones were complicit in the culture of professional songwriting that they would later critique and which they viewed as less authentic than the blues, gospel, or soul.

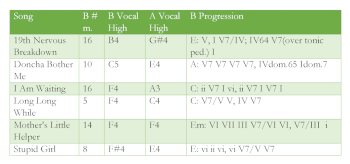

Example 15. Jagger-Richards songs for other artists

(click to enlarge)

Example 16. “Classic” bridges in Jagger-Richards songs for other artists

(click to enlarge)

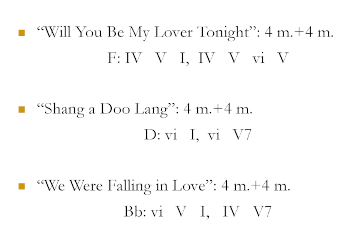

[3.2] Even as they focused their Rolling Stones performances and recordings on R&B and the blues between 1963 and 1965, Jagger and Richards wrote AABA songs for other pop artists to record, in most cases artists that were managed, produced, or publicized by the Stones’ producer Andrew Loog Oldham. Between late ‘63 and ‘65, Jagger and Richards wrote 17 such songs intended for other artists that were either recorded and released or exist today as unreleased full or partial demos (see Example 15). Nine of these 17 songs—a slight majority—were in AABA form, combined with mostly moderate tempos and lyrics that celebrated romance or lamented lost love. Example 16 includes examples of how the bridges in these songs tend towards the characteristics of de Clercq’s “classic” 1950s bridges, generally consisting of eight bars and following a simple two-phrase harmonic trajectory from predominant to dominant (2012, 74–77).(20) Jagger and Richards wrote these songs at the urging of Oldham—who later called the songs “soppy and imitative” (2000, 256)—and in imitation of the Lennon-McCartney partnership, in the hope of developing a new stream of income from royalties (2000, 251–52, 260).

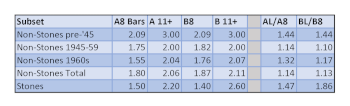

Example 17. Number of matches of Jagger-Richards songs for others and Stones songs with 1960s modes, out of 19 analytical categories

(click to enlarge)

[3.3] The songs that Jagger and Richards wrote for other artists differed strikingly from the early songs they wrote for their own band. Early in their careers they wrote mostly blues-based songs for the Stones but tended towards the mainstream AABA norms of the early 1960s in their songs for others. In Example 17 we can see the extent to which the Jagger-Richards AABA songs for others matched 1960–1964 mainstream norms. The early songs they wrote for the Stones to record (such as “Little by Little” and “Grown Up Wrong”) were generally not in AABA form and tended to rely on chord schemes, in particular 12-bar-blues and related patterns. In a 1964 interview, Richards said that “the Stones need relatively simple [songs] with very few chord changes in them” (2013, 6). But in their songs for other artists from this same time period, Jagger and Richards used AABA and avoided blues associations and chord schemes in verses, instead using mostly chord loops with a faster harmonic rhythm. This accorded with mainstream pop trends at the time, as the use of loop progressions in AABA verses reached a historic high in the early 1960s (see Example 10). Their songs for others“Give Me Your Hand,” “It Should Be You,” and “Wastin’ Time” all use chord loops in the A section, while Jagger and Richards mostly avoided loops in A sections for the Stones prior to 1967. In general, then, we see in the AABAs for others a generally faster harmonic rhythm and a closer connection to the harmonic approach of mainstream early 1960s pop. These early songs for others tended to use an SRDC melodic structure, which was very common in the early 1960s in other artists’ work. Rhythmically, Jagger and Richards favored moderate tempos and a straight 4/4 feel in their songs for others, rather than the blues shuffle they used in their early Stones songs. Lyrically, their songs for others tended towards gentle laments for lost love or optimistic celebrations of romance, while their early Stones originals were in many cases derisive and spiteful (e.g., “Little by Little” and “Grown Up Wrong”).

[3.4] Keith Richards said of his and Jagger’s early songs for other artists that “They had nothing to do with us, except we wrote ’em” (Obrecht 1993, 60). Richards sought to distance himself from these songs as a way of protecting the authenticity of the band. In Moore’s “first-person” formulation, artistic creations that are “authentic” ostensibly relate to the true self, while “inauthentic” ones are distanced from the true self (2002, 214). Richards and Jagger, in writing these songs, were taking on roles of professional songwriters in the Tin Pan Alley tradition, but Richards viewed this activity as detached from the “authentic” Richards and Jagger. The only way Richards and Jagger ultimately could write AABA songs in the later period, 1965–1967, was by treating the form ironically. Ironic treatment of AABA, a form associated with older styles of popular music, allowed for a more authentic expression of their inner selves: their denigration of the tradition of professional songwriting and of AABA form became an essential part of their music, rather than a stance hidden in order to compete in the songwriting market.

4. Stones AABAs as Ironic Critique

[4.1] The Stones’ AABA songs recorded between December 1965 and December 1966 were markedly different from those Jagger and Richards had previously written for others, as well as distinct from the AABAs written by other artists in the 1960s. In AABAs written for their band, Jagger and Richards mostly avoided the romantic lyrics typical of the form and at times made use of much faster tempos than were commonly associated with it. These characteristics distanced these Stones songs from AABAs of the 1960s, suggesting a parody of the earliest AABAs of the teens and 1920s.(21) The Stones recontextualized AABA form through use of fast tempos, misogynistic lyrics, electric guitar distortion, and a rough singing and playing style. These elements differed sharply from the musical qualities associated with the form in the 1960s. AABA was thus recontextualized and the form’s Tin Pan Alley associations made to seem ridiculous. Parody of an artistic norm is a critique not just of aesthetics but also of associated social norms (Harries 2000, 6). The Stones’ approach to AABA was part of rock’s “radical subversion of the culture represented by Tin Pan Alley song” (Middleton 1990, 43).

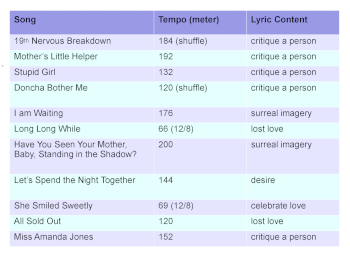

Example 18. Tempo and lyrics of Stones AABAs recorded 12/65–12/66

(click to enlarge)

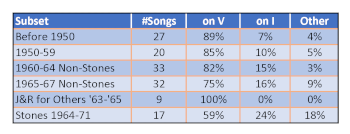

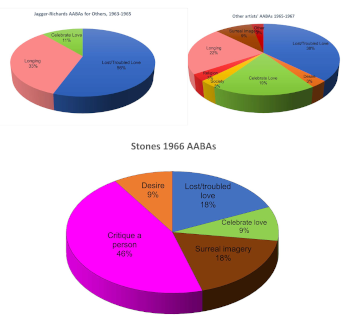

Example 19. Comparing lyrical content of AABAs

(click to enlarge)

[4.2] The lyrics of the Rolling Stones’ up-tempo AABAs in 1966–67, which included “19th Nervous Breakdown,” “Mother’s Little Helper,” “Stupid Girl,” “Have You Seen Your Mother,” and “Miss Amanda Jones,” avoid any trace of sentimentality or romance and indeed espouse an anti-romantic perspective that veers into misogyny.(22) While the 1963–65 songs Jagger and Richards wrote for other artists have been described (problematically) by Philip Norman as “romantic, even feminine” (2012, 136), their 1966 AABAs, listed in Example 18, contemptuously denounce women. The female subjects of “19th Nervous Breakdown,” “Mother’s Little Helper,” “Stupid Girl,” and “Miss Amanda Jones” are either wealthy or make pretensions of wealth and sophistication, and are subject to derision in the songs because of it. This critique of wealth via parody aligns with a long tradition of British working-class mockery of the upper classes in music (Dentith 2000, 31). The mother in “Mother’s Little Helper,” despite inhabiting the ostensibly safe space of the bourgeois family home, is derided for seeking “shelter” in drugs to escape stress, tiredness, and boredom. By comparison, the most popular AABA songs by other artists in these same years generally either convey optimism and romantic fervor—such as “The Birds and the Bees” and “Hold Me, Thrill Me, Kiss Me”—or sincerely lament lost or troubled love—as in the Mamas & the Papas’ “Monday, Monday” and Johnny Rivers’s “Poor Side of Town.” Example 19 compares the lyrical content in the Stones’ AABAs with that of other artists and with the early Jagger-Richards songs for others.

Example 20. Comparing AABA tempos

(click to enlarge)

[4.3] The tempos of the Stones’ AABA songs from this period also diverge significantly both from AABA songs performed by other artists and from those previously written by Jagger and Richards for other performers, in several cases replacing the moderate or slow tempos of typical 1960s AABAs with extremely fast tempos. Example 20 shows that the earliest twentieth-century AABA songs in the teens and 1920s tended towards faster tempos. The percentage of fast AABAs decreased over time, though, so that by the 1960s it was rare to hear a popular AABA with a very fast tempo. Contemporaneous AABA songs like “Cherish” and “Monday, Monday” had leisurely tempos as backdrops to their lyrical evocations of romantic love, either celebrated or lost, accompanied by lush backing vocal harmonies. The Beatles in their later years also tended to reserve AABA form for slower songs, in sharp contrast with the Stones’ approach. The Stones’ fast AABAs recall lively vaudeville and music hall numbers of the teens and 1920s, with “Puttin’ on the Ritz” (1930) being a late example, a song that was self-consciously vaudevillian at a time when vaudeville and music hall were in steep decline. Like “Puttin’ on the Ritz,” “Mother’s Little Helper” combines AABA form with a minor key, a fast tempo, and extended passages of static minor tonic harmony. These fast Stones AABAs also allude to Tin Pan Alley comic songs of the 1930s and 1940s, such as “Let’s Call the Whole Thing Off” (1937). Parody played a large part in the music hall tradition (Dentith 2000, 31), and the Stones’ AABAs in this period were grotesque descendants of that tradition.

[4.4] Examples 21 and 22 show the A1 sections of “Mother’s Little Helper” and “19th Nervous Breakdown.” Both are significantly expanded from the classic eight-bar Tin Pan Alley verse norm(23) and are harmonically based on chord schemes rather than wandering or loop approaches; both also exhibit slower harmonic rhythm and fast tempos. Chord schemes were rarely used in Tin Pan Alley AABAs unless songwriters were seeking to evoke country, blues, or folk associations (von Appen and Frei-Hauenschild 2015, 23). The Stones’ use of this harmonic approach, such as with the blues scheme in “19th Nervous Breakdown,” minimizes the Tin Pan Alley associations that normally accrue with AABA form. We hear a blues scheme and caustic, critical lyrics in the verses of the slower AABA “Doncha Bother Me” as well, with a text denigrating “copying” sung over a blues progression the Stones ultimately owed to Black musicians.

Example 21. “Mother’s Little Helper” (1966), first verse (click to enlarge, see the rest, and listen) | Example 22. “19th Nervous Breakdown” (1966), A1 Section (click to enlarge, see the rest, and listen) |

Example 23. Comparing AABA bridge harmonic progressions

(click to enlarge)

[4.5] In the bridges of the Stones’ 11 AABA songs recorded between December 1965 and December of the following year, Jagger and Richards turned away from the subdominant to dominant trajectory of classic ‘50s AABAs (and of the Jagger-Richards songs for other artists) but did not incorporate the chromaticism and modulation that characterized Tin Pan Alley and some '60s bridges. In some contemporaneous bridges like “Cherish” (1966), shown in Example 23, songwriters echoed the halcyon days of Tin Pan Alley by making extensive use of chromaticism and/or modulation, even while expanding beyond the traditional eight-bar limit.(24) Jagger and Richards, on the other hand, largely avoided relying on chromaticism, modulation, or harmonic sequences in their bridges recorded over this 13-month period. The stasis on tonic in the bridge of “Have You Seen Your Mother,” for instance, deviates from the tendency of “classic” bridges to avoid this harmony (de Clercq 2012, 78–79) and suggests self-conscious harmonic anti-sophistication.(25) The bridge of “Mother’s Little Helper” is the only Stones AABA among the 11 recorded between late 1965 and late 1966 with significant chromaticism, featuring prolonged tonicization of the major submediant.

Example 24. Aspects of the Stones AABA bridges recorded between December 1965 and March 1966

(click to enlarge)

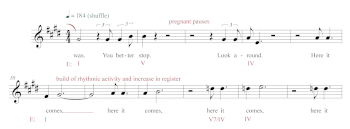

[4.6] The bridges in both “Mother’s Little Helper” and “19th Nervous Breakdown” serve more as standalone sections that act as the dynamic and formal high point of the song, in a fashion that conflicts with much AABA tradition (Example 24). Tin Pan Alley bridges, classic bridges from the 1950s, and the Jagger-Richards previous bridges for other artists tend to be subordinate sections of harmonic contrast that serve largely to renew the listener’s interest in the A section. In “Mother’s Little Helper” and “19th Nervous Breakdown,” however, the Stones shifted attention to the bridge itself as a focus of increased intensity.(26) In both cases this shift results in conflict with AABA tradition and an added sense of desperation in the songs. Richards and Jagger thereby also called attention to their use of a declining form, making the section that is the distinctive mark of the form (the bridge) longer and a focal point of the song. This is one of the main strategies for creating parody: a characteristic of the original is exaggerated, extended, or distorted (Dentith 2000, 32).

Example 25. “19th Nervous Breakdown,” end of verse 2 and the bridge

(click to enlarge, see the rest, and listen)

Example 26. “Mother’s Little Helper” (1966), bridge

(click to enlarge and listen)

[4.7] Example 24 shows that in four of their AABA bridges recorded between December ‘65 and March ‘66—in “Mother’s Little Helper,” “19th Nervous Breakdown,” “Doncha Bother Me,” and “I Am Waiting”—the return to tonic harmony at the end of the bridge provides tonal closure and makes the bridge more self-sufficient; it no longer serves as a tonal upbeat to the return of the verse.(27) In the bluesy “19th Nervous Breakdown” and “Doncha Bother Me,” landing on tonic at the end of the bridge results in an extended tonic prolongation that continues into the start of the verse. In “19th Nervous Breakdown” and “Mother’s Little Helper” the bridges feature registral ascents in the vocal line that further increase the independence of the section, making it the dynamic and formal climax of the song. In “19th Nervous Breakdown,” shown in Example 25, the tension is increased by the use of stop-time near the close of the bridge, and the reduced texture and silence in the drum kit make the falsetto “please” an even more dramatic high point. The word becomes almost unrecognizable due to the melismatic extension of the central phoneme. Its break from semantic meaning and into an alternate vocal tone evokes both the “nervous breakdown” of the subject of the song as well as a breakdown of the professionalism and sophistication of classic AABA form. The use of a tonic pedal under the dominant and the authentic resolution of it within the bridge on the high “please” further promotes a sense of closure that mimics the resignation of the narrator. The tonal resolution does not signal the end of the woman’s problems, but rather reflects the narrator’s giving up. In Example 26, the bridge of “Mother’s Little Helper” is 14 bars long and stylistically different from the verses. The Everly Brothers-style vocal harmonies in fourths and thirds and C-major tonicization contrast starkly with the E-minor stasis of the A sections. The generic disruption of this “weird ‘doctor, please’ C&W bridge” calls particular attention to this section (Davis 2001, 161), the ascending melodic sequence building to a high point as if to a drug high before the sobering comedown: “what a drag it is getting old.” The expansion of the bridge past eight bars in both “19th Nervous Breakdown” and “Mother’s Little Helper” makes tonal closure possible: in both songs, what could be a complete eight-bar bridge is presented, but then additional measures decrease the tension after the climax.

Example 27. The bridges of “Have You Seen Your Mother, Baby, Standing in the Shadow?” (1966) and “Let’s Spend the Night Together” (1967)

(click to enlarge, see the rest, and listen)

Example 28. “Classic” bridge progressions in three Stones AABAs

(click to enlarge and see the rest)

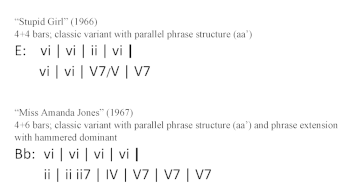

[4.8] In their AABA songs recorded between August and December 1966, Jagger and Richards continued to render their bridges as dynamic and formal climaxes, but in a different way. In these later songs they open the bridge with a texturally-reduced breakdown and dramatically build to a prolonged, “hammered” dominant rather than prematurely resolving to tonic (cf. Summach 2012, 62–63; Hepokoski and Darcy 2006, 34). This contrasting approach can be heard in “Have You Seen Your Mother” and “Let’s Spend the Night Together,” both shown in Example 27. Again, declining the first-level default of eight bars in the bridge allows for the section to be a greater focus of attention, in these instances allowing for a more sustained, lengthier build-up of tension than would typically be possible. These later bridges contrast with “19th Nervous Breakdown” and “Mother’s Little Helper” in avoiding tonic at the end of the bridge. They nonetheless carry greater weight and intensity on account of their greater length and the maximization of harmonic and registral tension. Notably, the bridges of both later songs occur only once, making them unique high points, while the two earlier songs have bridges that occur twice. “Have You Seen Your Mother” (released as a non-album single between the 1966 LP Aftermath and the 1967 album Between the Buttons) can be thought of as a transitional song for the Stones. Its highlighting of tonic harmony in the bridge echoes “19th Nervous Breakdown” and “Mother’s Little Helper,” while its textural reduction and gradual build to an intense dominant prolongation align it with certain bridges on the 1967 LP Between the Buttons, particularly those in “Let’s Spend the Night Together” and “She Smiled Sweetly.” “Stupid Girl,” “Miss Amanda Jones,” and “All Sold Out” share a biting, misogynistic lyrical commentary with “19th Nervous Breakdown” and “Mother’s Little Helper,” yet their bridges align more closely with the “classic” bridge progressions of the 1950s (see Example 28). In “We Love You,” recorded in the summer of 1967, the greater length of the bridge helps render it a mini-song within the song, creating a suite-like effect of the sort that would later become a staple of progressive rock in the 1970s.

Example 29. “Stray Cat Blues” (1968), bridge

(click to enlarge and listen)

[4.9] The bridge of the Stones’ 1968 release “Stray Cat Blues” (Example 29) differs significantly both from other Stones bridges and 1960s AABAs conventions, and the song’s formal aberrations carry expressive meaning. “Stray Cat Blues” has a ten-bar bridge built on a chromatic ascending fifths sequence. The harmonic sequence coincides with an increase in vocal range that makes this section the high point of the song and gives it chorus-like qualities. The bridge also resembles a chorus in that it, unusually, appears three times in the song, albeit once as primarily an instrumental. The threefold appearance of the bridge is sufficiently unusual in the context of 1960s pop songs as to qualify it as a lower-level default or even a deformation of norms (cf. Hepokoski and Darcy 2006, 614). The bridge-chorus meld here is reminiscent of de Clercq’s “blends” of multiple section types (2012, 213; 2017a, [1.6]; 2017b, 167; see also Nobile 2020, 141 regarding “Chorus-like B sections”).(28) The lyrical content of the song is transgressive, as it describes an encounter with two underage girls, and the exultant, sequential bridge suggests an illicit sexual climax. The frequent use of vocal syncopation in the bridge after relatively rhythmically square verses adds to the section’s intensity. In their use of a harmonic sequence as the basis of the bridge, the Stones allude to Tin Pan Alley traditions of harmonic sequence and bridge chromaticism, even while using lyrics and a style of singing completely at odds with that tradition. “Stray Cat Blues,” more than any other Stones AABA in this period, departs from the norms of 1960s AABAs, matching only seven out of the 19 norms of mid- to late-1960s AABAs observed in the output of other artists (refer back to Example 17). In addition to its unusual bridge, lyrics, and outro, the verses are an atypical ten bars long, divided into five phrases of two bars each in an aaabb structure. The deformations and stretching of norms are “expressive” in the words of Hepokoski and Darcy: “It is precisely the strain, the distortion of the norm . . . for which the composer strives at the deformational moment” (2006, 614). The formal deviance of the song matches the provocatively outré lyrics.

[4.10] AABA form’s associations with Tin Pan Alley and with the rapidly fading popular music mainstream of their parents’ generation were such that the Stones could have used the form nostalgically to celebrate an earlier era, in the manner of the Beatles’ vaudeville pastiches “Honey Pie” and “When I’m 64.” Instead, they undermined the idea of the past as a safe haven by twisting the form into a mockery of itself. The Stones viewed the blues and R&B as authentic and valuable, but treated popular styles like vaudeville and Tin Pan Alley with irony and derision in their 1966–67 releases because they viewed them as comparatively inferior (Faulk 2010, 84). The Rolling Stones refer to vaudeville, music hall, and Tin Pan Alley in “Mother’s Little Helper,” but preclude sentimentality through their use of scathing lyrics, a sitar-like electric 12-string guitar, a rough singing and playing style derived from American blues artists, and an extremely fast tempo. While the Beatles’ “Honey Pie” includes an introductory (“sectional”) verse in the manner of 1920s AABAs and affectionately invokes the past, Mick Jagger ironically alludes to the same introductory verse tradition with the acoustic-guitar-accompanied “What a drag it is getting old” at the start of “Mother’s Little Helper”. AABA form, itself an artifact of bourgeois leisure in historic decline, is the ideal vehicle to depict the apocalyptic end of civilization suggested in the AABA songs “Have You Seen Your Mother, Baby, Standing in the Shadow?” and “I Am Waiting.” The selection of a mother as a target of criticism in “Mother’s Little Helper,” “19th Nervous Breakdown,” and “Have You Seen Your Mother?” twists the specific Tin Pan Alley tradition of the “mother song” (Goldmark 2015, 15–16; Axford 2004, 19–20): the Stones viciously critique a mother rather than exalting her in the manner of Irving Berlin’s “You’ve Got Your Mother’s Big Blue Eyes” (1913) or “My Grandfather’s Girl” (1916). We see in the Stones’ “Mother’s Little Helper” and “Have You Seen Your Mother” the use of AABA form and a similarly rapid tempo as in “My Grandfather’s Girl,” but the polar opposite lyrical sentiment. Rather than a celebration of the maternal subject, vituperation and derision are heaped on the “mother” and, by extension, the previous generation.

[4.11] AABA form was the standardized tool of a commercial songwriting establishment that churned out a huge number of pop hits.(29) As such, the form for Jagger and Richards was analogous to the commercial products that bourgeois households like the one depicted in “Mother’s Little Helper” enjoyed. AABA songs were a mass-produced commercial commodity, with middle-class women having been the primary consumers of Tin Pan Alley sheet music (Goldmark 2015, 13). AABA form was used frequently by the Brill Building songwriters of 1959–1963 as well, whose music has been described as “conveyor-belt produced pop” that derived more from the Tin Pan Alley tradition than from the rock ‘n’ roll or rhythm and blues of the 1950s (Larkin 1997, 76; Stratton 2009a, 104–5; Scheurer 1996, 90). “Mother’s Little Helper” critiques the use of mass commodities like “instant cakes” and “frozen steaks,” implicitly including AABA songs among them. AABA form for the Stones is a product of consumer culture, an accessory to a banal “pursuit of happiness,” and is thus the perfect tool for a critique of that culture.(30) The Stones created irony by juxtaposing a symbol of professionalism and commercialism in pop music, AABA form, with an anti-professional approach in other aspects of these songs. The Stones rejected the idea of professionalism in seemingly every way possible, with their sloppy and uncoordinated dress, their rough and inexact style of playing instruments, Jagger’s and Richards’s rough style of singing, and—in pre-1968 recordings—their “anarchic” approach to recording and production (Oldham 2000, 232). The early 1960s was the heyday of girl groups, teen idols, and the Nashville Sound, a time when refined echo effects, orchestral accompaniments, and a sophisticated production style dominated the pop charts. The Stones’ early records represented an extreme departure from this approach, as the Stones sought to undermine the clean, refined sound of early 1960s pop with “garage rock” that critiqued bourgeois complacency by drawing on 1950s electric blues and R&B (Stratton 2009b, 39–40, 93; Titon 1993, 225). This rough aesthetic carried over into their AABA songs in the mid- and late-1960s. In combining AABA with a rough singing and playing style (and in some cases a harmonic scheme) derived from the blues, the Stones were creating parodic, shadow versions of the AABAs of mainstream pop music.

5. Stones AABA Ballads and Authenticity

Example 30. Stones AABA ballads, 1966–1971

(click to enlarge)

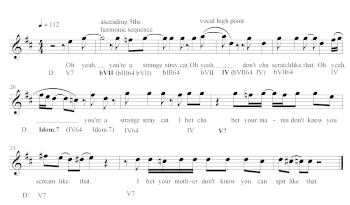

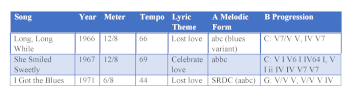

[5.1] The Stones between 1966 and 1971 used AABA form not just for up-tempo satirical songs, but also for compound-meter love ballads on their albums. “Long Long While,” “She Smiled Sweetly,” and “I Got the Blues,” shown in Example 30, are cases in point. These slower songs feature “classic” 1950s bridges that begin on a predominant harmony and end on the dominant. Soul and gospel music such as Otis Redding, Arthur Alexander, and Solomon Burke (all artists covered by the Stones), were major forces in the 1960s and exerted a strong influence on these Stones originals. The sarcasm, derision, and irony that appears in other Stones’ AABAs of this period are absent in their AABA ballads. For the Stones, soul ballads, despite their sincere love content, retained authenticity because they were performed by Black artists. The Stones tended to treat white-associated genres like Tin Pan Alley and country with derision and sarcasm (country examples include “Dear Doctor,” “Dead Flowers,” and “Far Away Eyes”), while treating genres like the blues, gospel, and soul with utmost sincerity and respect (Loewenstein and Dodd 2003, 120; Faulk 2010, 84). The Stones’ more sincere approach in “Long Long While,” “She Smiled Sweetly,” and “I Got the Blues” echoes the reverence they showed for Black blues and R&B artists in their earliest covers.(31) By 1966 the Stones had mostly given up recording covers and were instead writing original songs that were influenced by blues, soul, and R&B artists, but the sincerity in their approach in these songs remained a constant.

[5.2] The Stones, from 1964, recorded covers of African American artists who came from gospel backgrounds, among them Solomon Burke and Irma Thomas. The Stones sought third-person authenticity by performing these songs live and then in many cases recording them. Richards’s later statement reflecting on their early career that “We just wanted to be black motherfuckers” (Richards and Fox 2010, 104, 146), suggests the extent to which the Stones’ view of R&B and electric blues artists lacked any ironic distance. Like many other young British rock musicians in the 1960s, the Stones saw Black American musicians as more authentic than British pop stars like Cliff Richard and Adam Faith (Faulk 2010, 84). Gospel music itself did not use AABA form, yet the gospel approach to secular singing was brought to bear on a great many AABA songs by artists like Burke, Thomas, Otis Redding, and Sam Cooke. “Long Long While,” “She Smiled Sweetly,” and “I Got the Blues” all drew on the slow, soulful AABAs that the Stones covered early in their careers (such as “You Can Make It If You Try,” “Pain in My Heart,” and “Time is on My Side”).(32) Slow, flowing 12/8 meter, sincere lyrics about lost love, and AABA form were characteristics closely associated with Redding’s Stax ballads (Bowman 1995, 304). The Stones also imitated soul ballads in their use of a 12-bar blues-based chord scheme in the verse (“Long Long While” borrows this from “You Can Make It if You Try” and “Pain In My Heart”), the inclusion of an organ and/or brass instruments, and the omission of a recurrence of the bridge.(33)

Example 31. “Long Long While” (1966) vs. classic twelve-bar blues progression

(click to enlarge, see the rest, and listen)

[5.3] “Long Long While,” shown in Example 31, is an earnest Stones soul ballad from 1966 that serves as an example of this approach. Jagger here laments lost love, admitting “I was wrong, girl, and you were right.” In this song, the flowing 12/8 meter, the calm disposition of the initial A sections, the plagal cadences, and the use of an organ suggest religious sincerity of the sort that we hear in Elvis’s “Crying in the Chapel” (1965). The Stones thereby connect with soul’s church-based roots, even as the intonational discrepancies between the guitars and the rest of the band demonstrate anti-professionalism in a way that is completely at odds with the Elvis recording. The use of a blues-variant harmonic scheme in the verses also connects the song with a blues tradition that the Stones from the earliest days of the band associated with authenticity. The verses are initially subdued and even reverent, with the harmonic scheme covering six bars of 12/8 and a tripartite (abc) melodic structure also common in the blues. As seen in Example 31, the harmonic rhythm of the chord progression is hypermetrically displaced from the classic twelve-bar blues scheme, with chord changes occurring a half-bar earlier than expected. The hypermetric displacement dissonance imparts to the verses an unstable character reflective of the singer’s grief.(34) The progression realigns with the classic scheme by prolonging the subdominant, building anticipation before the plagal resolution to tonic. In the bridge, the distorted electric guitar becomes more prominent, Jagger’s vocal line rises in register and his mournful seriousness becomes soulful anguish, particularly in the second iteration of the bridge. The use of a V7/V at the start of the bridge provides an upwards chromatic boost of energy, the D7 chord temporarily giving the impression of a new tonic a whole step higher than the original C. The V–IV progression that follows is a blues signature that connects with the blues scheme of the verses and reinforces the connection with Black musical tradition. The four-bar length of the bridge creates a hypermetric disruption that echoes the displacement of harmonic rhythm in the verses: the triple hypermeter established by the 12-bar blues scheme is disrupted by a bridge that is two hyperbeats rather than the expected three. The bipartite division of the bridge aligns with the typical classic bridge structure, but this two-part division has a disruptive effect when combined with the triple hypermeter of the blues-based verses.

[5.4] As the song proceeds, Jagger’s lead vocal becomes increasingly anguished and soulful, creating a stark contrast between the reverence in the initial verses and the extreme emotions of the later verses. The tensing of Jagger’s vocal folds results in aperiodic vibration of the sort described by Heidemann in her categorization of vocal timbres (2016, [3.8]). His improvisatory, throaty exhortations and use of melisma in the second bridge and in the last two verses strongly evoke Black soul singers like James Brown and Otis Redding (Ripani 2006, 85). It is as if Jagger can only show the depths of his amatory anguish by putting his vocal cords in pain. Singing with a gravelly voice connotes that one has been shouting, screaming, or crying—or that one has lived a long life filled with tribulations. This connection with emotional intensity and emotional or physical pain, in turn, lends seriousness, credibility, and authenticity to a performer (Moore 2002, 212; Gilbert and Pearson 2002, 68–69). The increased improvisation and vocal tension in the later verses are accompanied by new chromaticism: an A major chord (V/ii) is surprisingly added at the conclusion of the verses starting with the fourth verse, immediately before the closing dominant. The use of this A major chord echoes the use of the V/V at the start of the bridge and is itself a chromatic energy boost that briefly suggests an ascending whole-step modulation before falling back to the expected dominant. The chromatic disruption complements the increasing agitation in Jagger’s singing as the song moves towards its final fadeout. This improvisatory build to a climax where “all parameters are intensified,” followed by a fadeout, echoes practice in Stax soul recordings of the 1960s (Bowman 1995, 295).

[5.5] The Stones’ approach in these slower songs was the antithesis of their approach in their ironic AABAs, where their mission was ridicule and irreverence. In seemingly every other way the band was opposed to sincerity and sweetness: they put images of toilets and zippers on their album covers, channeled the devil in their song and album titles, and used heavily distorted guitars on songs like “Satisfaction” and “All Sold Out.” Yet in their ballad AABAs they sought sincerity. Their imitation of gospel- and soul-infused Black artists like Solomon Burke and Irma Thomas echoed their earlier attempts to emulate Black American blues artists like Muddy Waters and R&B performers like Bo Diddley. In both cases the Stones seemed to believe they could channel the historic oppression of African Americans and give a weight and seriousness to their music that it could not otherwise have. Such music did not just allow for a sincere approach, but actually demanded sincerity. The attempt to connect not just with the Black experience of oppression but also with religion is a crucial element of the Stones’ songs in this vein. While these songs are not explicitly religious, the organs on these tracks connect their lyrical themes of lost love with the seriousness of the Christian church. The regret of breaking up with a girlfriend was thus compared to spiritual penitence. Jagger had little interest in his early days in “maudlin” country songs (Loewenstein and Dodd 2003, 120), yet the gospel and soul traditions of Mahalia Jackson and Sam Cooke represented authenticity for him and the Stones. The young white British musicians in bands such as the Rolling Stones, Cream, and Led Zeppelin accepted without question the notion that American Blacks had greater authenticity (Faulk 2010, 84) and that this authenticity could be accessed by performing the music of Black musicians and imitating their manner of performance. Sincerity in approaching such music and in songs derived from that music was for the Stones not a conservative, reactionary choice, but instead another way of rejecting white bourgeois values.

6. Conclusion

[6.1] The Stones made extensive use of AABA in their 1966 and 1967 releases but used it only occasionally in the subsequent period covering 1968 to 1971. “Stray Cat Blues,” “Salt of the Earth,” “I Got the Blues,” and “Sway” are the only AABAs they released in this latter period. The Stones’ turn to roots music on 1968’s Beggars Banquet included a renewed interest in strophic form and verse-chorus form. These trends continued on the Stones’ 1972 double-album Exile on Main Street, which contained only one AABA among its 18 tracks, “Loving Cup.” The Stones’ ironic use of AABA form foreshadowed their self-conscious, at times ironic treatment of country music on albums from Beggars Banquet to Some Girls. Their approach to AABA also set a precedent for later artists, particularly punk musicians of the mid- to late-1970s like the Sex Pistols and the Ramones, who similarly combined self-conscious use of AABA form with a frenzied pace and a rough singing and playing style (von Appen and Frei-Hauenschild 2015, 74–75). While in the early 1960s AABA form represented professionalism in music, by the mid-1970s it was associated with the deliberate amateurism and simplicity of punk.

[6.2] We see in the Stones’ AABA songs of the 1960s both sides of the coin—parody and critical distance on the one hand, and a sincere identification with a tradition on the other. These dual approaches resonate not just in the history of popular song form but also in discussions of race and class in popular music in the 1960s more generally. The question of the authenticity of Black artists and of white artists seeking to imitate and identify with them, as well as critical engagement with the previous generation’s artistic tradition, are issues that are relevant to a myriad of artists throughout the 1960s, 1970s, and beyond. We can see these themes playing out not just in lyrical content but also in the specific musical details of songs. These include formal particulars and harmonic and textural decisions that may not be consciously recognized by listeners but that nevertheless play a crucial role in the listening experience.

David S. Carter

Loyola Marymount University

Music Department

1 LMU Drive

Los Angeles, CA 90045

david.carter2@lmu.edu

Works Cited

Adorno, Theodor W. 2009. “On Popular Music.” In Current of Music, edited by Robert Hullot-Kenter, 271–326. Polity Press.

Altham, Keith. 1967. “The Rolling Stones: Between the Buttons (Decca).” New Musical Express. January 14. http://www.rocksbackpages.com/Library/Article/the-rolling-stones-between-the-buttons-decca.

Axford, Elizabeth. 2004. Song Sheets to Software: A Guide to Print Music, Software, and Web Sites for Musicians. 2nd ed. Scarecrow Press.

Biamonte, Nicole. 2014. “Formal Functions of Metric Dissonance in Rock Music.” Music Theory Online 20 (2). https://doi.org/10.30535/mto.20.2.1.

Billboard. “Chart Search.” https://www.billboard.com/charts/search.

Bogdanov, Vladimir, Chris Woodstra, and Stephen Thomas Erlewine. 2002. All Music Guide to Rock: The Definitive Guide to Rock, Pop, and Soul. Backbeat Books.

Bowman, Rob. 1995. “The Stax Sound: A Musicological Analysis.” Popular Music 14 (3): 285–320. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0261143000007753.

Callahan, Michael R. 2013. “Sentential Lyric-Types in the Great American Songbook.” Music Theory Online 19 (3). https://doi.org/10.30535/mto.19.3.2.

Caplin, William. 1998. Classical Form: A Theory of Formal Functions for the Instrumental Music of Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven. Oxford University Press.

Coelho, Victor. 2019. “Exile, America, and the Theater of the Rolling Stones, 1968–1972.” In The Cambridge Companion to the Rolling Stones, ed. Victor Coelho and John Covach, 57–74. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781139343336.005.

Cortens, Evan. 2014. “The Expositions of Haydn’s String Quartets: A Corpus Analysis.” HAYDN: Online Journal of the Haydn Society of North America 4 (1). https://www.rit.edu/affiliate/haydn/sites/rit.edu.affiliate.haydn/files/article_pdfs/cortenspdfmer.pdf.

Cott, Johnathan. 1968. “Mick Jagger: The Rolling Stone Interview.” Rolling Stone, October 12. http://www.rollingstone.com/music/news/the-rolling-stone-interview-mick-jagger-19681012.

Covach, John. 2005. “Form in Rock Music: A Primer.” In Engaging Music, ed. Deborah Stein, 65–76. Oxford University Press.

—————. 2006. “From ‘Craft’ to ‘Art’: Formal Structure in the Music of the Beatles.” In Reading the Beatles: Cultural Studies, Literary Criticism, and the Fab Four, ed. Kenneth Womack and Todd Davis, 37–53. SUNY Press.

—————. 2010. “Leiber and Stoller, the Coasters, and the ‘Dramatic AABA’ Form.” In Sounding Out Pop: Analytical Essays in Popular Music, ed. Mark Spicer and John Covach, 1–17. University of Michigan Press. https://doi.org/10.3998/mpub.105283.

—————. 2019. “The Rolling Stones in 1968: In Defense of Lingering Psychedelia.” In The Cambridge Companion to the Rolling Stones, ed. Victor Coelho and John Covach, 40–56. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781139343336.004.

Davis, Stephen. 2001. Old Gods Almost Dead: The 40-Year Odyssey of the Rolling Stones. Broadway Books.

de Clercq, Trevor. 2012. “Sections and Successions in Successful Songs: A Prototype Approach to Form in Rock Music.” PhD diss., Eastman School of Music. https://urresearch.rochester.edu/fileDownloadForInstitutionalItem.action;jsessionid=FE003231CA6318973A6B6575EDC63709?itemId=23612&itemFileId=73869.

—————. 2017a. “Embracing Ambiguity in the Analysis of Form in Pop/Rock Music, 1982–1991.” Music Theory Online 23 (3). https://doi.org/10.30535/mto.23.3.4.

—————. 2017b. “Interactions Between Harmony and Form in a Corpus of Rock Music.” Journal of Music Theory 61 (2): 143–70. https://doi.org/10.1215/00222909-4149525.

Dentith, Simon. 2000. Parody. Routledge.

DigitalDreamDoor.com. 2009a. “100 Greatest Popular Songs of the 1920s.” https://digitaldreamdoor.com/pages/best_songs-1920s.html.

—————. 2009b. “100 Greatest Popular Songs of the 1940s.” https://digitaldreamdoor.com/pages/best_songs-1940s.html.

—————. 2010. “100 Greatest Popular Songs of the 1930s.” https://digitaldreamdoor.com/pages/best_songs-1930s.html.

di Perna, Alan. 2002. “Heart of Stone.” Guitar World 22 (10) (Oct.). https://www.guitarworld.com/gw-archive/rolling-stones-keith-richards-looks-back-40-years-music-gimme-shelter-interview.

Endrinal, Christopher. 2011. “Burning Bridges: Defining the Interverse in the Music of U2.” Music Theory Online 17 (3). https://doi.org/10.30535/mto.17.3.6.

Everett, Walter. 2001. The Beatles as Musicians: The Quarry Men Through Rubber Soul. Oxford University Press.

Faulk, Barry J. 2010. British Rock Modernism, 1967–1977: The Story of Music Hall in Rock. Ashgate.

Fitzgerald, Jon. 1996. “Lennon-McCartney and the ‘Middle Eight’.” Popular Music and Society 20 (4): 41–52. https://doi.org/10.1080/03007769608591643.

—————. 1999. “Musical Form and the Early 1960s Pop Song.” In Musical Visions, ed. Gerry Bloustien, 35–42. Wakefield.

Geyer, Ben. 2019. “Maria Schneider’s Forms: Norms and Deviations in a Contemporary Jazz Corpus.” Journal of Music Theory 63 (1): 35–70. https://doi.org/10.1215/00222909-7320462.

Gilbert, Jeremy, and Ewan Pearson. 2002. Discographies: Dance, Music, Culture and the Politics of Sound. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203012062.

Goldmark, Daniel. 2015. “‘Making Songs Pay’: Tin Pan Alley's Formulas for Success.” The Musical Quarterly 98 (1–2): 3–28. https://doi.org/10.1093/musqtl/gdv012.

Graziano, John. 2013. “Compositional Strategies in Popular Song Form of the Early Twentieth Century.” Gamut 6 (2): 95–132.

Hamm, Charles. 1979. Yesterdays: Popular Song in America. W.W. Norton.

—————. 1995. Putting Popular Music in Its Place. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511895500.

Harries, Dan. 2000. Film Parody. British Film Institute.

Hawtin, Steve, et al. 2019a. “Songs from the 1910s.” Version 2.8.0044. https://tsort.info/music/ds1910.htm.

—————. 2019b. “Songs from the 1920s.” Version 2.8.0044. https://tsort.info/music/ds1920.htm.

—————. 2019c. “Songs from the 1930s.” Version 2.8.0044. https://tsort.info/music/ds1930.htm.

—————. 2019d. “Songs from the 1940s.” Version 2.8.0044. https://tsort.info/music/ds1940.htm.

Heidemann, Kate. 2016. “A System for Describing Vocal Timbre in Popular Song.” Music Theory Online 22 (1). https://doi.org/10.30535/mto.22.1.2.

Hepokoski, James. 1989. “Genre and Content in Mid-Century Verdi: ‘Addio, del passato’ (“La traviata”, Act III).” Cambridge Opera Journal 1 (3): 249–76. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954586700003025.

Hepokoski, James, and Warren Darcy. 2006. Elements of Sonata Theory: Norms, Types, and Deformations in the Late-Eighteenth-Century Sonata. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195146400.001.0001.

Horton, Julian. 2017. “Criteria for a Theory of Nineteenth-Century Sonata Form.” Music Theory and Analysis 4 (2): 147–91. https://doi.org/10.11116/MTA.4.2.1.

Hutcheon, Linda. 1988. A Poetics of Postmodernism: History, Theory, Fiction. Taylor & Francis.

Hutcheon, Linda, and Malcolm Woodland. 2012. “Parody.” In The Princeton Encyclopedia of Poetry and Poetics, ed. Roland Green, Stephen Cushman, and Clare Cavanagh. 4th ed. Princeton University Press.

Hymes, Dell H. 1974. Foundations in Sociolinguistics: An Ethnographic Approach. University of Pennsylvania Press.

Julien, Olivier. 2018. “From ‘Sectional Refrains’ to Repeated Verses: The Rise of the AABA Form.” In Over and Over: Exploring Repetition in Popular Music, ed. Oliver Julien and Christophe Levaux, 107–16. Bloomsbury. https://doi.org/10.5040/9781501324871.ch-007.

Karnbach, James, and Carol Benson. 1997. It’s Only Rock ‘n’ Roll: The Ultimate Guide to the Rolling Stones. Facts on File.

Larkin, Colin. 1997. The Virgin Encyclopedia of Sixties Music. Virgin Books.

Loewenstein, Dora, and Philip Dodd, eds. 2003. According to the Rolling Stones. Chronicle Books.