Review of Drew Nobile, Form as Harmony in Rock Music (Oxford University Press, 2020)

Alyssa Barna

DOI: 10.30535/mto.28.1.10

Copyright © 2022 Society for Music Theory

[1] Analytical and theoretical studies of popular repertoires proliferate on conference programs and in scholarly publications today, and publications of complete monographs that treat rock and pop with an analytical lens are common. Drew Nobile’s monograph, Form as Harmony in Rock Music, is a welcome and highly anticipated contribution to the subfield. Scholars who are familiar with Nobile’s output, in numerous articles and engaging conference presentations, will be pleased with the comprehensive account of the relationship of harmony and form present throughout the book.

[2] While Nobile cites and integrates existing scholarship on harmony and form in rock music, he also adeptly carves his own path, indicating how his work differs from that of others, including Walter Everett, David Temperley, Trevor De Clercq, or Christopher Doll. The task of defining the repertoire under consideration is as vital as the discussion of relevant scholarship. Nobile takes great pains to discuss what distinguishes “Rock” from “rock,” and focuses on repertoire of the more inclusive “small-r” version of the term that encompasses a larger swath of genres, leaving “capital-R Rock” as a label for a specific genre (xxi–xxii). This useful distinction eases the sometimes-contentious relationship between the broad genres of rock (small-r) and pop music. This contention is derived from the problem that it is nearly impossible, given the fast-paced growth and plurality of genres in the 20th-century popular music, to classify songs as specifically “rock” or “pop.” Because Nobile’s choice of repertoire ends in 1991, he avoids the ever-expanding hybridity of genres that began to occur at the turn of the 21st century and that continues in current popular music releases. Changes in style in rock composition at the beginning of the 1990s were motivated by the rise in popularity of new genres such as hip-hop and alternative rock. These new styles typically demand a different set of analytical techniques than that demanded by small-r rock that came before. In all, Nobile’s “small-r” designation is useful for popular music from 1960–1991.

[3] The integration of Schenkerian techniques with a close study of form and harmony is a hallmark of Nobile’s work, both in this book and in previous scholarship (Nobile 2011, 2016). The theory of harmony presented in the book relies on the idea of prolongation; Nobile offers “an adaptation of Schenkerian theory tailored to rock’s harmonic idiom” (xx). With few exceptions, Form as Harmony does not utilize advanced Schenkerian techniques and vocabulary, so readers with limited understanding of Schenker’s methodologies as applied to Western art music will still be able to understand the bulk of the analytical narrative.(1)

[4] Chapter 1 sets out Nobile’s theory of harmony, in particular his concept of a “functional circuit” as “a harmonic trajectory spanning a complete formal unity, comprising the syntactical harmonic functions of tonic, pre-dominant, dominant, and back to tonic (T–PD–D–T)” (5). The final section explains that cadences are essential to the closure of the functional circuit. Nobile draws explicitly on Caplin’s discussion of cadences as involving simultaneous harmonic and formal closure (Caplin 2004), arguing that a cadence in the repertoire under consideration must coincide with the end of a complete functional circuit (34). He does so in order to demonstrate the interaction of harmony and form in functional circuits, and later, in large-scale forms. His approach goes further than other rock analysts who do not require harmonic closure as a condition for cadences; Nobile characterizes their approach as merely cadence-as-punctuation (Temperley 2018, Stephenson 2002, Doll 2017). To properly marry harmony and form in functional circuits, the condition of harmonic closure seems necessary.

Example 1. Nobile’s Table 3.1, 93

(click to enlarge)

[5] Chapters 2 and 3 classify verses and choruses according to the harmonic language present in each type. There are two types of verses: “sectional” and “initiating.” Sectional verses complete a functional circuit and are usually cast in a small form, such as aaba, srdc (statement, restatement, departure, conclusion), or a blues progression. In contrast, initiating verses do not complete a functional circuit, do not cadence, and typically prolong the tonic. Thus, initiating verses cannot stand alone and must lead to a chorus to complete harmonic closure. Following his discussion of verses, Nobile divides choruses into three sections: “sectional,” “continuation,” and “telos.” “Sectional choruses are the counterparts to sectional verses,” (73) and both sectional verses and choruses convey a sense of autonomy. Continuation choruses, like initiating verses, do not contain a functional circuit; they often begin off tonic but cadence by the end. Lastly, telos choruses prompt the audience to “rock out,” most commonly over a tonic prolongation. Example 1 shows Nobile’s Table 3.1, which summarizes the chorus types, and helpfully adds non-harmonic markers to the sections, indicating how lyrics, audience, and melodic/thematic structure play a significant part in the interpretation of a section.

[6] Chapter 4 details the defining features of such sections as prechoruses, bridges, and a wide array of auxiliary sections. The definitions in this chapter are helpful when one encounters a section that does not fit the norms of a verse or chorus. These types of units can appear frequently, as is the case for the prechorus, or infrequently, as with the “overture chorus,”(2) (120) and this section provides a useful reference to assist analysts in appropriately labeling sections based on their harmonic content and contextual role in the large-scale form.

[7] At the conclusion of chapter 4, Nobile notes that while his method will help analysts label formal units in a song, its purpose is broader than simply applying names to sections: “Figuring out what sections occur in what order is certainly useful, but it says nothing about how a song’s component sections relate to one another” (124). He notes that he intends to “[build] from the premise that focusing on individual chord-to-chord successions tells us little about rock’s overall harmonic organization” (1), which reads as a critique of the more granular and/or corpus-based harmonic analytical work done by De Clercq and Temperley (2011) and Doll (2017) over the last decade. Instead, in Nobile's view, we should strive to discover how these component parts combine to create a “cohesive musical structure” which is “fundamental to a connection of form as process” (124). The following chapters, accordingly, “zoom out” to discuss how harmonic and formal processes connect to create various larger-scale formal layouts.

[8] Chapters 5 through 8 show how normative patterns arise from the interaction of form and harmony in the following formal layouts. Within complete verse-chorus forms, the terms “sectional” and “continuous” are used to describe the formal design. Sectional layouts are harmonically separable and often contrasting, and continuous verse-chorus layouts have codependent sections. In the final layout type, verse-prechorus-chorus, the insertion of a prechorus significantly affects the perception of form, as this insertion can alter the hypermeter and phrase rhythm and can also blur the boundaries between verse and chorus. In these chapters, many of Nobile's analyses contain both a transcribed excerpt and a voice-leading graph showing the harmonic-melodic structure. This helps illuminate how, in examples of continuous verse-chorus form and verse-prechorus-chorus form, the functional circuits of the song rely on the full layout of the song for completion. The distinction between sectional and continuous forms is not superfluous: the terminology describes not just the nature of the section itself, but also the context and relationship between juxtaposed sections. The transcription and graph examples offer the fullest picture of how harmony sets expectations and contributes to teleology in song form.

[9] The intended audience of the book is scholars of music theory and analysis, especially those who are already well-versed in the corpus of rock between 1960–1991. But Nobile’s writing style is accessible to readers beyond the academic community, and the musical examples are clear and well-formatted, so that any reader who reads music will be able to get the gist of his general argument from what is contained in the figures. Often, a detailed example is followed by a short list of several other songs that follow the same principles. (These listed examples are either addressed in another chapter, or Nobile simply states the title and artist of additional songs for the reader to investigate on their own.) Students or junior scholars who focus their interests on post-millennial music will gain exposure to a wide variety of songs, as Nobile uses many compelling and understudied examples from the second half of the 20th century.

[10] Form as Harmony in Rock Music could be used for teaching in two ways. First, a teacher could excerpt examples for undergraduate students at various levels in order to analyze form or harmony in the context of a core undergraduate class. A teacher could easily adapt one or more of the examples from any chapter in the book to demonstrate concepts such as harmonic progression, functional syntax in rock, or more general traits of formal sections. For example, first-year instructors looking to move beyond fundamentals and common-practice repertoire can borrow Nobile’s examples of 12-bar blues patterns (59, 128), and teach students how harmonic progressions are often inextricably tied to form. For more advanced students with greater fluency in harmonic analysis, instructors could use examples like Blondie’s “Heart of Glass” or the Beach Boys’ “In My Room” to teach various types of mixture (130, 133) alongside examples from Western art music. The second, broader, application of this text in a classroom setting could be in specialized courses on popular music at the undergraduate or graduate level. The book could easily serve as the core text for a course or seminar devoted to the study of form in rock and pop music. In this scenario, rather than organizing the course chronologically through decades of repertoire, each chapter (or pair of chapters) could serve as a different unit throughout the semester. Students would then synthesize and apply the concepts found in the text and any other supplementary scholarship to analyze songs of their choosing. As previously mentioned, while not completely necessary for understanding the primary concepts of this book, some preliminary knowledge in linear or Schenkerian analysis is necessary to accurately follow the more in-depth analyses. This issue points to a broader concern about the use of Schenkerian theory in this book, especially in a pedagogical context: what is lost if the reader—students or otherwise—do not have a firm grasp of Schenkerian techniques?

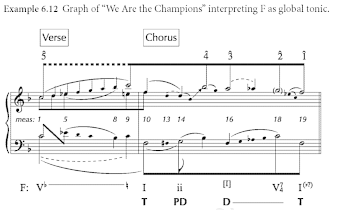

Example 2. Nobile’s Example 6.12, 166

(click to enlarge)

[11] For example, in his analysis of Queen’s “We Are the Champions,” Nobile analyzes the verse, which begins in C minor, as a secondary area, which then resolves to the global tonic of F major as found in the chorus (164–166). Thus, the functional circuit begins and ends in the chorus. Example 2 contains Nobile’s example 6.12 shows a voice-leading graph of the song. Students without experience in prolongational analysis may be able to follow the general idea outlined by the voice-leading in the figure. They will, however, miss nuances in the argument provided by terminology such as a linear ascent or upper thirds, or the significance of a chromatically-inflected descent or expanded dominant progression. If the aforementioned goals of this book are to promote the study of “form as process” and the creation of a “cohesive musical structure” (124), then the details leading to this cohesion and process are not fully clear to the reader without prior study. Furthermore, are voice-leading and harmony really the primary drivers of cohesion and form-as-process? This mindset restricts the study of other parameters—especially rhythm, text, and timbre—and constricts narrative opportunities that rely on the confluence of different musical domains.

[12] Nobile justifies his cutoff date of 1991 by arguing that that the use of harmony as the chief parameter in the determination of form begins to shift in 1991, due to, among other factors, the rise of hip-hop and grunge. Indeed, musical parameters such as rhythm and timbre gained traction and influence in music-analytic scholarship in the last decade of the 20th century and continue to do so into the present, and the role and syntax of harmony continues to change.(3) Thus it is important that Nobile selects this timeframe so as to not overextend his theory into repertoire that would be inappropriate for the tools introduced in this book. His account of the role that parameters beyond harmony play in the rock music between the 1960s and 1991 is less developed. There are gestures towards rhythm and timbre in the introductory and concluding materials, but scholars looking to apply Nobile's apparatus to recent music will have to carefully consider how they might extend the techniques and theories of this book when analyzing harmony and form in recent pop and rock. Nobile has already pursued and presented work on harmony and form in post-millennial popular and rock music (2015, 2019), and I look forward to additional extensions of this work addressing newer popular music and a wider variety of musical domains.

[13] As readers proceed through the numerous analytical examples, they may notice that both the musical examples and citations are weighted towards artists and scholars who are men, many of whom are white. An informal count of artists listed in the index indicates 187 artists or bands that exclusively comprise men, and 31 women artists or bands.(4) The neglect of woman artists is nothing new. Gender bias has and continues to perpetuate through decades of academic and cultural discourse, leading to disproportionate recognition and fame for men. For example, less than 8% of the inductees into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in the past 34 years have been women (Barnett 2020). Resources currently exist to help raise the profile of woman artists working in the genres of both rock (small-r) and Rock (capital-R).(5) I believe, with a bit of targeted effort to diversify the repertoire, some of the less popular artists and one-hit-wonders in Nobile's book might have easily been replaced with prominent woman rockers like Pat Benatar or Joan Jett and the Blackhearts.

[14] The scholarly citations found in the book are also not immune to this oversight. In the bibliography, 14 women are represented in the scholarly sources compared to 66 men. This may be representative of the topics at hand (namely, rock harmony, Schenkerian analysis, and rock studies) for which the readings considered foundational to the fields are largely written by white men, and therefore necessitate several citations of white men.

[15] In Form as Harmony in Rock Music Nobile adeptly illustrates the inextricable relationship between harmony, melody, voice-leading, and form in rock between 1960 and 1991, accounting for both norms and many exceptions to those norms. Its value to the field was recently acknowledged by the Society for Music Theory, which awarded Nobile the Emerging Scholar Award for the book. This monograph will certainly become essential reading for scholars and students looking to expand their knowledge and skills in analyzing and deeply engaging with rock music.

Alyssa Barna

College of Liberal Arts

University of Minnesota

215 Johnston Hall

101 Pleasant St. S.E.

Minneapolis, MN 55455

barna@umn.edu

Works Cited

Barnett, David C. 2020. “Women Make Up Less Than 8% Of Rock and Roll Hall of Fame Inductees.” NPR Music News, January 14, 2020. https://www.npr.org/2020/01/14/796012607/women-make-up-less-than-8-of-rock-and-roll-hall-of-fame-inductees

Biamonte, Nicole. 2014. “Formal Functions of Metric Dissonance in Rock Music.” Music Theory Online 20 (2). https://www.mtosmt.org/issues/mto.14.20.2/mto.14.20.2.biamonte.html

Branstetter, Leah. 2019. “Women in Rock and Roll's First Wave.” Ph.D. Dissertation, Case Western Reserve University. http://www.womeninrockproject.org/

Caplin, William E. 2004. “The Classical Cadence: Conceptions and Misconceptions.” Journal of the American Musicological Society 57 (1): 51–118.

Danielsen, Anne, 2015. “Metrical Ambiguity or Microrhythmic Flexibility? Analysing Groove in ‘Nasty Girl’ by Destiny’s Child.” In Song Interpretation in 21st-Century Pop Music, ed. Ralf von Appen, André Doehring, Dietrich Helms, and Allan F. Moore, 53–71. Ashgate Publishing

De Clercq, Trevor. 2016. “Measuring a Measure: Absolute Time as a Factor for Determining Bar Lengths and Meter in Pop/Rock Music.” Music Theory Online 22 (3). https://mtosmt.org/issues/mto.16.22.3/mto.16.22.3.declercq.html

De Clercq, Trevor and David Temperley. 2011. “A Corpus Analysis of Rock Harmony.” Popular Music 30 (1): 47–70.

Doll, Christopher. 2017. Hearing Harmony: Toward a Tonal Theory for the Rock Era. University of Michigan Press.

Ewell, Philip. 2020. “Music Theory and the White Racial Frame.” Music Theory Online 26 (2). https://mtosmt.org/issues/mto.20.26.2/mto.20.26.2.ewell.html

Heidemann, Kate. 2016. “A System for Describing Vocal Timbre in Popular Song.” Music Theory Online 22 (1). https://mtosmt.org/issues/mto.16.22.1/mto.16.22.1.heidemann.html

Lavengood, Megan. 2020. “The Cultural Significance of Timbre Analysis: A Case Study in 1980s Pop Music, Texture, and Narrative.” Music Theory Online 26 (3). https://mtosmt.org/issues/mto.20.26.3/mto.20.26.3.lavengood.html

Malawey, Victoria. 2020. A Blaze of Light in Every Word. Oxford University Press.

Nobile, Drew. 2011. “Form and Voice Leading in Early Beatles Songs.” Music Theory Online 17 (3). https://www.mtosmt.org/issues/mto.11.17.3/mto.11.17.3.nobile.html

—————. 2015. “Counterpoint in Rock Music: Unpacking the ‘Melodic-Harmonic Divorce.’ Music Theory Spectrum 37 (2): 189–203.

—————. 2016. “Harmonic Function in Rock Music: A Syntactical Approach.” Journal of Music Theory 60 (2): 149–180.

—————. 2019. “Anti-Telos Choruses in Recent Pop.” Presentation at the annual meeting of the Society for Music Theory, Columbus, OH.

—————. 2020. Form as Harmony in Rock Music. Oxford University Press.

Stephenson, Ken. 2002. What to Listen for in Rock: A Stylistic Analysis. Yale University Press.

Temperley, David. 2018. The Musical Language of Rock. Oxford University Press.

Footnotes

1. Instructors and readers might focus on the prolongational aspects of the book's analyses, rather than seeing them as rooted in the depths of Schenker’s ideas, given discourse on Schenker's bigoted beliefs (Ewell 2020). However, one may argue that even an adaptation of techniques may be rooted in white supremacy, and this should be considered by readers.

Return to text

2. An overture chorus occurs when the chorus section is featured as the opening of the song, offering a preview of the chorus before it appears within the song’s full form. Nobile notes that “overture choruses evoke the folk tradition of instructional choruses, which are sung right away in order to teach the audience the words so they can sing along with future iterations” (120).

Return to text

3. For examples of recent scholarship that focus on parameters beyond harmony in rock and pop, see Heidemann 2016, Lavengood 2020, or Malawey 2020 on timbre. On rhythm, see Biamonte 2014, Danielsen 2015, or De Clerq 2016. This is a very small sample of what are now two very large fields of study in rock and pop.

Return to text

4. I counted any ensemble that had at least one woman in it as “woman.”

Return to text

5. For example, see Leah Branstetter’s site “Women in Rock and Roll’s First Wave,” as well as the accompanying dissertation (2019), which documents the history of woman musicians in rock from the 1950s and 60s.

Return to text

Copyright Statement

Copyright © 2022 by the Society for Music Theory. All rights reserved.

[1] Copyrights for individual items published in Music Theory Online (MTO) are held by their authors. Items appearing in MTO may be saved and stored in electronic or paper form, and may be shared among individuals for purposes of scholarly research or discussion, but may not be republished in any form, electronic or print, without prior, written permission from the author(s), and advance notification of the editors of MTO.

[2] Any redistributed form of items published in MTO must include the following information in a form appropriate to the medium in which the items are to appear:

This item appeared in Music Theory Online in [VOLUME #, ISSUE #] on [DAY/MONTH/YEAR]. It was authored by [FULL NAME, EMAIL ADDRESS], with whose written permission it is reprinted here.

[3] Libraries may archive issues of MTO in electronic or paper form for public access so long as each issue is stored in its entirety, and no access fee is charged. Exceptions to these requirements must be approved in writing by the editors of MTO, who will act in accordance with the decisions of the Society for Music Theory.

This document and all portions thereof are protected by U.S. and international copyright laws. Material contained herein may be copied and/or distributed for research purposes only.

Prepared by Fred Hosken, Editorial Assistant

Number of visits:

5873