Review of Amy Cimini, Wild Sound: Maryanne Amacher and the Tenses of Audible Life (Oxford University Press, 2022)*

Noah Kahrs

KEYWORDS: electronic music, feminism, acoustics, listening, attention

DOI: 10.30535/mto.28.4.9

Copyright © 2022 Society for Music Theory

1.

[1.1] Six years ago, I was practicing glockenspiel and heard a buzzing sound that seemed to come from inside my ears. After I reassured myself that I wasn’t damaging my hearing, I realized that I could easily replicate certain buzzes’ pitches by playing specific dyads. The buzzes were combination tones: my eardrum was vibrating in such a way that it supplied new, lower pitches in response to the high, loud notes from the glockenspiel. After I mentioned this experience, a mentor directed me towards Maryanne Amacher’s music, which provided an example of how one could use the eardrum musically. Yet much of Amacher’s work remained a mystery to me—the combination tones were bracing, of course, but I couldn’t quite figure out what she wanted them to do in her music’s broader context. Amy Cimini’s Wild Sound: Maryanne Amacher and the Tenses of Audible Life helped me finally unpack all that those combination tones had to offer, showing me how Amacher’s music could help me hear not just combination tones but many other aspects of sound at the margins of what one usually listens for.

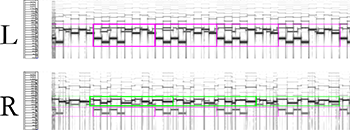

Example 1. The opening of “Head Rhythm” from Maryanne Amacher’s Sound Characters: Making the Third Ear, with characteristic motives highlighted

(click to enlarge and listen)

[1.2] To make the experience of combination tones a little more concrete, let’s listen to a bit of Amacher’s music. Example 1 presents the opening of the first track, “Head Rhythm 1 and Plaything 2,” from her first commercially-released album, Sound Characters: Making the Third Ear (Amacher 1999). A lightly annotated spectrogram highlights repeated ostinatos. (Caution: for combination tones to emerge, the track has to be piercingly and almost painfully loud. I have provided both a reduced-volume version, which may not induce combination tones without volume boosting on the reader’s end, and an original which will; however, I urge you to turn down your volume before listening, then increase it until the combination tones emerge.) In the left channel is a recurring pattern of four low notes and four high notes moving by perfect intervals, bracketed in pink. In the right channel sits a narrow warble, bracketed in green. But the passage’s most distinguishing feature is not any of the notes that appear in the spectrogram. If one listens with speakers instead of headphones and at a sufficiently loud volume, a few much lower notes emerge within an octave of middle C, coming not from the speakers but from inside the listener’s head. Those are the sorts of combination tones I heard when practicing glockenspiel.

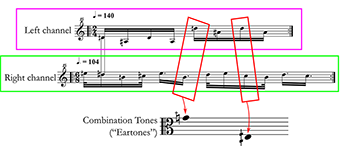

Example 2. Transcription and analysis of combination tones in “Head Rhythm,” with audio slowed 4x

(click to enlarge, interact, and listen)

[1.3] Most often, the easiest combination tones to hear are difference tones, whose frequency corresponds to the difference between the frequencies of the two sounding notes.(1) To calculate which difference tones could emerge in our ears in response to “Head Rhythm 1,” we can transcribe the recurring ostinati, determine the frequencies of the tones therein, and subtract the corresponding frequencies. Example 2 contains my transcription of the first complete appearances of the ostinati highlighted in Example 1. The corresponding audio example is slowed down 4x both so that one can clearly hear how the ostinati leap and warble, and so that one can process their dyads’ emergent combination tones more clearly.(2) Beneath the transcription, I have notated the two combination tones that protrude most prominently to my ear, which are just sharp of G4 and E3. These are the two notes I heard emerge in Example 1’s full-speed recording, and they are particularly clear in Example 2’s slower recording. (Red boxes identify the sounding pitches that create the difference tones; click on them to see my calculation of difference tones and to hear the direct juxtaposition of the sounded notes and the emergent pitch.) In its overt use of combination tones, “Head Rhythm 1” is a virtuosic manipulation of the human ear’s physiology, taking advantage of a phenomenon long contemplated by music theorists.

[1.4] Although Amacher’s music is well known for its use of combination tones,(3) analyses limited to this aspect of her music are insufficient. Of the seven tracks on her 1999 CD, only three contain any combination tones at all. And despite being known for combination tones, Amacher is just as often considered a founding figure of sound art who is primarily concerned not with the intricacies of the ear’s physiology but rather with bigger questions of how technology can bring faraway sounds close to us, or immerse us in sounds coming from all directions (Adams IV 2019, 230–33; Cox 2018, 13–15; Licht 2019, 5–8, 52–61).(4) Furthermore, listeners approaching Amacher’s work face not just the intellectual challenge of negotiating these distinct interests, but also the more practical issue that much of Amacher’s work is accessible only in fragmented form. She released only two complete CDs (Amacher 1999; 2008); otherwise we have only a few audio excerpts of installations interspersed throughout various anthologies (Wolff et al. 2010; Ziegler and Gross 2000; Collins and Christensen 1990); a handful of talks that made their way into print (Amacher [1977] 2008; [1995] 2018; Maconie et al. 2008; Mumma et al. 2001); and a recent volume that assembles short excerpts from her archival papers (Cimini and Dietz 2020). Beyond these published materials lies a vast realm of installations, live broadcasts, and other projects that left few traces behind. When her materials are so fragmentary, how can we even begin to make connections between Amacher’s many projects, which suggest so many disparate approaches to the very act of listening?

[1.5] Amy Cimini’s Wild Sound: Maryanne Amacher and the Tenses of Audible Life solves these problems by pulling together many strands from across Amacher’s life and weaving them into a narrative of how Amacher consistently pursued, through her music, a few specific theoretical and epistemological questions. Cimini synthesizes feminist perspectives on science and on mind-body dualism—drawing not only from music theory and musicology but also from Amacher’s unpublished notes on her readings in philosophy of science—to contextualize how Amacher reinvigorates the capacity to direct one’s attention when listening. Cimini’s analytical readings establish through-lines across Amacher’s wide-ranging works by establishing points of commonality, both via conceptual priorities and shared sonic material, across music spanning decades of her career. In Cimini’s hands, Amacher’s music emerges as constantly recasting familiar musical concepts across new contextual terrains. Thanks to Cimini’s close readings, it becomes clear both how Amacher’s earlier works can help us understand her later ones, and how Amacher’s theoretical declarations can help us more generally reimagine how we can listen.

2.

[2.1] Cimini’s first chapter introduces her project’s foundation in feminist philosophy of science. It presents Donna Haraway’s essay “Situated Knowledges” ([1988] 1991) as a nodal point linking Amacher to contemporaneous discourses in music theory. Haraway’s essay is a shared foundation both for Amacher’s own theoretical thought, as shown by handwritten notes in her archives, and for Suzanne Cusick’s foundational essay in feminist music theory (1994), which serves as Cimini’s primary theoretical model. In making this connection, Cimini draws on her previous discussions of Cusick’s essay (Cimini 2012; 2018b; Cimini and Moreno 2016) to interpret Amacher’s work as bringing together mind and body. In Cimini’s reading, Amacher presented herself as a “composer-theorist” in the modernist, mind-focused sense (5, 49), but remained deeply aware of how the social and political implications of contemporaneous technology constructed her embodied relationship with her music.

[2.2] This music demands a lot of its audience. To consider the sorts of listening it asks for, Cimini turns to writings by Amacher’s close devotee (and Cimini’s occasional coauthor), Bill Dietz. The word “tenses” in her book’s subtitle comes from Dietz’s characterization of Amacher as a “composer in the subjunctive” (Dietz 2009). According to Dietz, Amacher’s works require listeners to refocus their ears to hear sounds that may or may not be there (Dietz 2011), to listen for how a sound might contain “life,” or a “shimmer inside” (73; Cimini 2020; Rodgers 2011). To create music that pushes listeners to take such active roles, Amacher turned away from traditional concert works and towards immersive broadcasts and installations. The requisite listening practices, and their places within Amacher’s value system, are revealed through Cimini’s extensive treatment of archival materials. Summarizing how her book reconstructs Amacher’s “subjunctive” listening, Cimini describes it as “a field guide for imagining sounds in ways that Amacher seems to have done,” both as Amacher helps us to in her music and as she did in her compositional process (41).

[2.3] Chapter 2 shows how Amacher puts subjunctive listening into practice in her 1960s compositions. Amacher’s core technique is to focus aural attention on a specific frequency range in a sound’s spectrum. Cimini refers to such a strategy as spectral attention. Of course, such listening has been around for a long time, and fits into recent theoretical discourses on the eighteenth century (Raz 2022) and nineteenth century (Steege 2012; Hui 2012, 89–121; 2021). But by deploying attention itself as an object for composition and performance, Amacher moves far beyond these precedents. In Adjacencies (1965), Amacher’s final concert-hall work and the primary focus of the chapter, percussionists are instructed to play instruments while attempting to produce sounds in certain frequency bands. For an ensemble consisting largely of metal percussion instruments with inharmonic spectra, the notation provides the performers not with explicit details of how to perform with their instruments, but instead indicates which sounds they should attempt to find. The piece gives the music theorist much to contemplate: the performers subjunctively wish for sounds, requiring them to strain their ears as part of the performance process, and by delegating such authority to the performers, Amacher pushes against the usual distinction between composer and performer.

[2.4] Chapters 3 and 4 demonstrate that spectral attention remains useful for coming to terms with Amacher’s compositions, dating from the 1970s and 80s, that use environmental sounds and combination tones. In both chapters, Cimini uses Amacher’s unpublished working notes, which suggest various listening strategies, as the basis for her analyses of Amacher’s pieces from the same period. Chapter 3, expanding on an earlier article (Cimini 2017b), reads Amacher’s essay LONG DISTANCE MUSIC in conjunction with Amacher’s use of live sound transmissions (110). Amacher placed microphones across cities, leased dedicated telephone lines for them, and brought the sounds into her studio or installation spaces. In addition to encouraging spectral attention, whether by playing specific pitches near microphones or providing hints through program notes and gallery wall text, Amacher’s exhibits highlighted their own dependence on the shifting technology of the telephone industry and on the particular locations, often former industrial sites, where microphones were installed. Chapter 4 deals with combination tones, using Amacher’s handwritten notes on Roederer’s Introduction to the Physics and Psychophysics of Music (1975) to show how combination tones fit into her broader theorizing. Roederer’s text helped Amacher to direct her attention to what she called the “perceptual geography” of sounds: whether they originated in the room, in her ear, or in her brain. Cimini’s analysis of “Head Rhythm 1” points to the many frequency ranges to which Amacher could have directed attention, linking intervallic configurations to what Amacher, according to her own working notes, hoped to be able to hear.

[2.5] In Chapter 5, Cimini follows Amacher on a speculative turn, unpacking the myriad signifiers in Amacher’s 1980 installation Living Sound (Patent Pending). At the acoustical level, the installation consisted of an entire house in which viciously loud sounds traveled through the walls, swirling around listeners as they moved through the building. But Cimini focuses less on the sounds than on the technoscientific discourse influencing the visual “clues” Amacher placed throughout the exhibit, as shown in archival photographs. The “living sound” of the title refers to fictitious microbes allegedly contained in actual petri dishes placed throughout the house. The microbes’ ostensible musical activities are described by texts on the walls. (“Patent pending” in the work’s title refers to the Supreme Court’s Diamond v. Chakrabarty, from the same year as the installation, which declared human-made bacteria to be patentable.) Cimini concludes the book with a few of Amacher’s unfinished and even more speculative projects concerning what music could be in the future. There are few if any audible traces of these projects available, leaving us to imagine what they might have sounded like. Sketches for her unfinished TV opera Intelligent Life, for instance, ask how computers might predict and react to combination tones to match a listener’s preferences (see also Cimini 2017a). In a lecture after Cage’s death, she imagined how music could extend beyond the limits of duration once CDs and LPs were obsolete (Mumma et al. 2001).

3.

[3.1] At the end of the book, spectral attention becomes less of a unifying thread; the actual sounds of Amacher’s music recede in favor of the philosophical stances Amacher envisioned her work as taking. Cimini’s fifth chapter places Amacher within her cultural context, relating the installation Living Sound (Patent Pending) to Amacher’s engagement with contemporaneous scientific questions about life. In interpreting the installation through the lens of the Diamond v. Chakrabarty case, Cimini certainly illuminates the work’s intended meaning, matching her earlier success in using legal cases to interpret a more recent sound installation (Cimini 2018a) and music theory’s diversity initiatives (Cimini and Moreno 2009). But after reading the previous chapters’ more concrete listening strategies, I found myself wishing for a bit more detail about Amacher’s sounds.

Audio Example 3a. “Boston Harbor” from Living Sound (Patent Pending) (recording on Ziegler and Gross 2000), 0:03–0:18

Audio Example 3b. “Spirals” from Living Sound, 2:43–2:54

Audio Example 3c. “Here” from Living Sound, 3:00–3:39

Audio Example 3d. Archival tape for Amacher’s preparatory work on Adjacencies, passage perhaps corresponding to Audio Example 3c. From Kumpf 2017, 28:20–29:15

Example 4. Shared motives between Living Sound (Audio Example 3c) and preparatory tape (Audio Example 3d)

(click to enlarge and listen)

[3.2] To be fair, the end of Chapter 5 does contain enough details that one can trace a few common materials across Amacher’s recorded output. In the one commercially available excerpt from Living Sound, “buried at the end of the third disc” (259) of a compilation canonizing pre-2000 electronic works (Ziegler and Gross 2000), Cimini identifies three “sound characters” (Amacher’s term for sounds with distinctive and consistent shapes) borrowed from previous recordings. The excerpt begins with Audio Example 3a’s recordings from Boston Harbor (captured by a microphone placed amidst post-industrial decay as in Chapter 3) and soon layers one of Living Sound’s most distinct sonic features, Audio Example 3b’s nasal, synthesizer-based “Spirals.” The last character to enter, nestled among these, is Here, heard simultaneously with “Spirals” in Audio Example 3c. Here builds on earlier work. It originated as a companion piece to Chapter 2’s Adjacencies and sounds vividly similar to an archival tape of Amacher’s exploration of harp techniques, provided in Audio Example 3d (from Kumpf 2017). Example 4 shows that these excerpts share characteristic gestures, such as two sonorities moving by melodic semitone, and high-register plucked fifths.

[3.3] As enriching as I find these musical details in my own listening, they are not central to Cimini’s argument. Although she frequently consults archival recordings for historical evidence, she does not undertake much detailed analysis of the sounds, which might be a direction for future research on Amacher. Cimini’s source-identification analysis for Living Sound arrives after she explicates most of Amacher’s visuo-textual clues, and its relevance to the installation is again more philosophical than auditory. Because several sound characters originate in works discussed in earlier chapters, Cimini interprets them as alluding to the same techniques of listening. For example, one might imagine the inner life of a harp sound much as one imagines the sounds fictitiously coming from microbes. But it remains unclear whether the actual sounds matter, as opposed to only their points of origin in Amacher’s earlier work.

[3.4] Along similar lines, I should note that specific recordings are seldom mentioned in the rest of the book. This is surprising, given that Cimini is clearly deeply knowledgeable about extant recorded materials. Fortunately for the interested reader, some archival recordings can be found online. In addition to the tape of Audio Example 3d, Kumpf’s 2017 Blank Forms podcast, made to celebrate Adjacencies’ first performance in decades, contains a 1966 rehearsal recording of Adjacencies and the final 20 minutes of Amacher’s 1967 broadcast of live urban sounds in Buffalo. That podcast is an indispensable companion to Cimini’s Chapter 2. For Chapter 3, one might consult the brief recording of Boston Harbor identified in Audio Example 3a, as well as a recording made for Merce Cunningham’s ballet “Remainder” (243–44, Wolff et al. 2010). In Chapter 4, Cimini references the commercially available “Head Rhythm 1” to demonstrate some implications of Amacher’s theoretical notes from decades earlier. Even if such recordings are not always essential to Cimini’s argument, one may still find these audio excerpts helpful.

[3.5] Cimini occasionally brings in other composers’ music as foils for Amacher’s, whether to highlight the broader applicability of Amacher’s theories or her music’s uniqueness. The first few comparisons helpfully situate Amacher among her peers and teachers, but some later comparisons, to more distant composers, may suggest too simple a picture of Amacher. Chapter 2’s comparisons start off convincingly: Cimini’s reading of Adjacencies extends to Karlheinz Stockhausen’s Mikrophonie I, clarifying a teacher-student legacy and how careful use of microphones can emphasize sounds’ overtones; it also extends to Anthony Braxton’s Composition No. 9, whose theatrical presentation of performers shoveling coal highlights the political concerns implicit in the interpretive freedom Amacher allows her performers (76–82). Chapters 3 and 4, in keeping with Chapter 1’s description of Amacher’s feminist epistemology, juxtapose her music against that of male composers who interpret environmental sounds and combination tones through more “objective” lenses, without regard to the nuances of how their audience members listen. I might add, however, that in using technology to highlight listeners’ subjective experiences, Amacher is aligned with several of her contemporaries, and future research might highlight both shared and distinct features of Amacher’s interests in feminism, embodiment, and subject formation.

[3.6] In particular, Amacher is not the only woman who, through foundational electronic music, considered how a listener’s hearing of environmental sounds or combination tones is influenced by the listener’s relationship with their own body, perhaps as mediated by technology. In Chapter 3, Cimini quite sensibly distinguishes Amacher’s City-Links series from R. Murray Schafer’s and Barry Truax’s attempts to present environmental sounds as existing outside of the contingencies of history in soundscape compositions (123–29). To this conversation, one might add a reference to Hildegard Westerkamp. Despite being affiliated with the same World Soundscape Project as Schafer and Truax, Westerkamp is, in works such as Kits Beach Soundwalk, much more direct in showing listeners how their sense of hearing is being artificially manipulated. Accordingly, such pieces lend themselves to feminist-epistemological readings much like Cimini’s (McCartney 1999, 1–10, 193–227, 309–35; Rodgers 2010, 18). Likewise, in Chapter 4, Cimini briefly analyzes Jacob Kirkegaard’s use of combination tones in “Labyrinthitis,” whose vocabulary of possible combination tones is much more restricted than Amacher’s, and which presents them so that only one new pitch can emerge at a time, in a model of what Cimini considers medicine-like sterility (187–90). Pauline Oliveros might provide an even more revealing comparison. Oliveros remains an iconic composer for feminist music studies (see Mockus 2011; Oliveros and Maus 1994; Rodgers 2010), and her early work, much like Amacher’s work from decades later, features an embodied and gendered exploration of combination tones (Gordon 2022, 387, 394–99). She does briefly appear in a few footnotes, but since she was, like Amacher, committed to a synthesis of electronic music and feminist practice, I would have appreciated a more sustained discussion. To be clear, I do not mean to suggest that Amacher’s music is in any way derivative of these composers’. Oliveros herself described Amacher’s work as “quite unique and very powerful” (Schimana and Tikhonova 2014, 24:15). But such comparisons could have helped to clarify more nuances of Amacher’s music and feminism, particularly as it involves the in-time nature of a listener’s experiences.

4.

[4.1] Over the past few years, several SMT plenary talks have asked how music theory might have established a different set of core techniques and values if we counted more work, particularly that of women, as belonging to the field (Hisama 2021; Maus 2020). From that vantage, Cimini’s book helps us imagine what our field might look like if we counted Amacher as a member. Amacher repeatedly invokes the epistemic authority of the “composer-theorist” as a model for her own work (28, 49). By asking listeners to assume agency in shaping their attention, she blurs the line between listener and performer. Instead of presuming mind and body to be distinct sources of knowledge, a prerequisite for the centrality of the body to Cusick’s program of feminist music theory, Amacher’s music instead demonstrates how our mindful listening can already be embodied (Cusick 1994; Cimini 2012; 2018b). Like Alexandra Pierce, Amacher shows how music-theoretical conventions and bodily actions can inform and enrich one another (Maus 2020, Pierce 1978).

[4.2] Much like Maus’s counter-canonical figures of the 1970s—Pierce, Oliveros, and Helen Bonny— Amacher was successful in her own right outside of constrained academic environments. She “did not need SMT” (Maus 2020), a society concerned, in Amacher’s words, with “pushing around other men’s notes” (279).(5) But we music theorists would surely gain from re-learning the basic elements of listening, as recast through Amacher’s new perspectives. Wild Sound can help all of us rethink how to hear and imagine sounds.

Noah Kahrs

Eastman School of Music

Department of Music Theory

26 Gibbs St

Rochester, NY 14604

nkahrs@u.rochester.edu

Works Cited

Adams IV, George William. 2019. “Listening to Conceptual Music: Technology, Culture, Analysis.” PhD diss., University of Chicago. https://doi.org/10.6082/uchicago.2006.

Amacher, Maryanne. 1999. Sound Characters (Making the Third Ear). Tzadik.

—————. [1977] 2008. “Psychoacoustic Phenomena in Musical Composition: Some Features of a ‘Perceptual Geography.’” In Arcana III: Musicians on Music, ed. John Zorn, 9–24. Hips Road/Tzadik.

—————. 2008. Sound Characters 2: Making Sonic Spaces. Tzadik.

—————. [1995] 2018. “Untitled Lecture.” In Eight Lectures on Experimental Music, ed. Alvin Lucier, 45–58. Wesleyan University Press.

Cimini, Amy. 2012. “Vibrating Colors and Silent Bodies: Music, Sound and Silence in Maurice-Merleau-Ponty’s Critique of Dualism.” Contemporary Music Review 31 (5–6): 353–70. https://doi.org/10.1080/07494467.2012.759411.

—————. 2017a. “In Your Head: Notes on Maryanne Amacher’s Intelligent Life.” The Opera Quarterly 33 (3–4): 269–302. https://doi.org/10.1093/oq/kbx025.

—————. 2017b. “Telematic Tape: Notes on Maryanne Amacher’s City-Links (1967–1980).” Twentieth-Century Music 14 (1): 93–108. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1478572217000081.

—————. 2018a. “Walking to the Gallery: Sondra Perry’s ‘It’s in the Game’ in San Diego in Five Fragments.” Sound Studies 4 (2): 178–200. https://doi.org/10.1080/20551940.2018.1612646.

—————. 2018b. “Music Theory, Feminism, the Body: Mediation’s Plural Work.” Contemporary Music Review 37 (5–6): 666–83. https://doi.org/10.1080/07494467.2018.1577642.

—————. 2020. “We Don’t Know That We Don’t Know What a Body Can Do

Cimini, Amy, and Bill Dietz, eds. 2020. Maryanne Amacher: Selected Writings and Interviews. Blank Forms.

Cimini, Amy, and Jairo Moreno. 2009. “On Diversity.” Gamut: Online Journal of the Music Theory Society of the Mid-Atlantic 2 (1). https://trace.tennessee.edu/gamut/vol2/iss1/6.

—————. 2016. “Inexhaustible Sound and Fiduciary Aurality.” Boundary 2 43 (1): 5–41. https://doi.org/10.1215/01903659-3340625.

Collins, Nicolas, and Don Christensen. 1990. Imaginary Landscapes: New Electronic Music. Elektra Nonesuch.

Cox, Christoph. 2018. Sonic Flux: Sound, Art, and Metaphysics. University of Chicago Press. https://doi.org/10.7208/chicago/9780226543208.001.0001.

Cusick, Suzanne G. 1994. “Feminist Theory, Music Theory, and the Mind/Body Problem.” Perspectives of New Music 32 (1): 8–27. https://doi.org/10.2307/833149.

Dietz, Bill. 2009. “Bill Dietz on Maryanne Amacher.” Kammer Klang (blog), November 12. https://www.kammerklang.co.uk/events/maryanne-amacher-interview/.

—————. 2011. “Composing Listening.” Performance Research 16 (3): 56–61. https://doi.org/10.1080/13528165.2011.606026.

Gordon, Theodore. 2022. “‘Androgynous Music’: Pauline Oliveros’s Early Cybernetic Improvisation.” Contemporary Music Review 40 (4): 386–408. https://doi.org/10.1080/07494467.2021.2001939.

Haraway, Donna. [1988] 1991. “Situated Knowledges: The Science Question in Feminism and the Privilege of Partial Perspective.” In Simians, Cyborgs, and Women: The Reinvention of Nature, 183–201. Routledge.

Hasegawa, Robert. 2015. “Clashing Harmonic Systems in Haas’s Blumenstück and in vain.” Music Theory Spectrum 37 (2): 204–23. https://doi.org/10.1093/mts/mtv014.

Helmholtz, Hermann L. F. [1885] 1954. On the Sensations of Tone as a Physiological Basis for the Theory of Music. Translated by Alexander J Ellis. Dover.

Hisama, Ellie M. 2021. “Getting to Count.” Music Theory Spectrum 43 (2): 349–63. https://doi.org/10.1093/mts/mtaa033.

Hui, Alexandra. 2012. The Psychophysical Ear: Musical Experiments, Experimental Sounds, 1840–1910. MIT Press. https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/9460.001.0001.

—————. 2021. “Ernst Mach’s Piano and the Making of a Psychophysical Imaginarium.” In Interpreting Mach: Critical Essays, ed. John Preston, 10–27. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108564311.002.

Iverson, Jennifer. 2018. Electronic Inspirations: Technologies of the Cold War Musical Avant-Garde. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780190868192.001.0001.

Kahrs, Noah. 2021. “Experimental Music’s Critiques of Triadic Theory.” Paper presented at Music Theory Society of New York State, online, August.

Kirk, Jonathon. 2010. “Otoacoustic Emissions as a Compositional Tool.” In International Computer Music Conference Proceedings, 316–18. New York. http://hdl.handle.net/2027/spo.bbp2372.2010.063.

Kumpf, Lawrence. 2017. “Blank Forms #21: Maryanne Amacher’s Adjacencies.” SoundCloud audio, 01:33:39. Blank Forms. https://soundcloud.com/blankforms/maryanne-amachers-adjacencies.

Licht, Alan. 2019. Sound Art Revisited. Bloomsbury. https://doi.org/10.5040/9781501333163.

Maconie, Robin, Irvine Arditti, Morton Subotnick, Pierre-Laurent Aimard, La Monte Young, Maryanne Amacher, and Björk. 2008. “Music of the Spheres: Reflections on Karlheinz Stockhausen.” Artforum, March. https://www.artforum.com/print/200803/music-of-the-spheres-reflections-on-karlheinz-stockhausen-41995.

Maus, Fred. 2020. “Music Theory in the 1970s and 1980s: Three Women.” Plenary talk presented at the Society for Music Theory Annual Meeting, online, November 14.

McCartney, Andra. 1999. “Sounding Places: Situated Conversations through the Soundscape Compositions of Hildegard Westerkamp.” PhD diss., York University.

Mockus, Martha. 2011. Sounding out: Pauline Oliveros and Lesbian Musicality. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203935590.

Mumma, Gordon, Allan Kaprow, James Tenney, Christian Wolff, Alvin Curran, and Maryanne Amacher. 2001. “Cage’s Influence: A Panel Discussion.” In Writings through John Cage’s Music, Poetry, and Art, ed. David W. Bernstein and Christopher Hatch, 167–89. University of Chicago Press. https://doi.org/10.7208/chicago/9780226044873.001.0001.

Neely, Adam. 2019. YouTubers React to Experimental Music. YouTube video, 9:01. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PVvOemu-ZTk.

Oliveros, Pauline, and Fred Maus. 1994. “A Conversation about Feminism and Music.” Perspectives of New Music 32 (2): 174–93. https://doi.org/10.2307/833606.

Pierce, Alexandra. 1978. “Structure and Phrase (Part I).” In Theory Only 4 (5): 22–35. https://quod.lib.umich.edu/g/genpub/0641601.0004.005/24.

Raz, Carmel. 2022. “To ‘Fill Up, Completely, the Whole Capacity of the Mind’: Listening with Attention in Late Eighteenth-Century Scotland.” Music Theory Spectrum 44 (1): 141–54. https://doi.org/10.1093/mts/mtab012.

Rodgers, Tara. 2010. Pink Noises: Women on Electronic Music and Sound. Duke University Press. https://doi.org/10.1515/9780822394150.

—————. 2011. “‘What, for Me, Constitutes Life in a Sound?’: Electronic Sounds as Lively and Differentiated Individuals.” American Quarterly 63 (3): 509–30. https://doi.org/10.1353/aq.2011.0046.

Roederer, Juan G. 1975. Introduction to the Physics and Psychophysics of Music. Springer-Verlag. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4615-9981-4.

Schimana, Elisabeth, and Lena Tikhonova. 2014. IMAfiction #06 13 Maryanne Amacher. Vimeo video, 32:29. https://vimeo.com/87401740.

Steege, Benjamin. 2012. Helmholtz and the Modern Listener. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139057745.

Wolff, Christian, Gordon Mumma, Takehisa Kosugi, John King, Paul M. Tai, Jean Rigg, David Behrman, and Stephan Moore. 2010. Music for Merce: 1952–2009. New World Records.

Ziegler, Thomas, and Jason Gross. 2000. OHM: The Early Gurus of Electronic Music, 1948–1980. Ellipsis Arts.

Footnotes

* I would like to thank Sam Pluta, for introducing me to the music of Maryanne Amacher right when I needed it most; Zachary Bernstein, Hanisha Kulothparan, Elizabeth West Marvin, and MTO’s editorial staff, for reading various drafts of this review; and Miles Jefferson Friday, for much valuable conversation about Amacher’s work.

Return to text

1. Difference tones have been observed by music theorists for centuries (Iverson 2018, 81–82, 101–2; Helmholtz [1885] 1954, 214–16; Steege 2012, 58–60).

Return to text

2. For visual simplicity, in lieu of exact pitches in Hertz or cents, I have rounded each note to the nearest twelfth-tone, with Georg Friedrich Haas’s twelfth-tone notation (Hasegawa 2015, 207).

Return to text

3. “Chorale 1,” a later track on her Sound Characters album, is the clearest exemplar of combination tones, and several analyses of it have focused on this aspect (Kahrs 2021; Kirk 2010; Neely 2019).

Return to text

4. Although Amacher did not appreciate being considered a “sound artist,” particularly as it narrowed her exhibition and funding possibilities (49n11 of the reviewed text; Cimini and Dietz 2020, 11), it’s impossible to escape the simple fact that, despite her wishes, she is identified as a founding figure of sound art.

Return to text

5. I am grateful to Fred Maus for sharing the script for his plenary talk, and for suggesting the particular relevance of Alexandra Pierce.

Return to text

Copyright Statement

Copyright © 2022 by the Society for Music Theory. All rights reserved.

[1] Copyrights for individual items published in Music Theory Online (MTO) are held by their authors. Items appearing in MTO may be saved and stored in electronic or paper form, and may be shared among individuals for purposes of scholarly research or discussion, but may not be republished in any form, electronic or print, without prior, written permission from the author(s), and advance notification of the editors of MTO.

[2] Any redistributed form of items published in MTO must include the following information in a form appropriate to the medium in which the items are to appear:

This item appeared in Music Theory Online in [VOLUME #, ISSUE #] on [DAY/MONTH/YEAR]. It was authored by [FULL NAME, EMAIL ADDRESS], with whose written permission it is reprinted here.

[3] Libraries may archive issues of MTO in electronic or paper form for public access so long as each issue is stored in its entirety, and no access fee is charged. Exceptions to these requirements must be approved in writing by the editors of MTO, who will act in accordance with the decisions of the Society for Music Theory.

This document and all portions thereof are protected by U.S. and international copyright laws. Material contained herein may be copied and/or distributed for research purposes only.

Prepared by Andrew Eason, Editorial Assistant

Number of visits:

3947