Review of Matthew Santa, Hearing Rhythm and Meter: Analyzing Metrical Consonance and Dissonance in Common-Practice Music (Routledge, 2020)

David Temperley

KEYWORDS: rhythm, meter, metrical dissonance, phrase rhythm

DOI: 10.30535/mto.28.4.10

Copyright © 2022 Society for Music Theory

[1] I think many would agree that work on rhythm and meter in music theory represents one of the field’s most notable accomplishments over the last 50 years. Contributions by authors such as Lerdahl and Jackendoff (1983), Rothstein (1989), Krebs (1999), Schachter (1999), Cohn (2001), London (2004), and Mirka (2009), as well as many others, have greatly advanced our understanding of rhythm and meter in common-practice music. While these theorists sometimes use different terms and focus on different aspects of the topic, their ideas are largely complementary and compatible; together, these ideas form a powerful, unified theoretical framework.

[2] Up to now, this recent work on rhythm and meter has had little impact on the music theory classroom. Most theory curricula for undergraduates and graduate-level performers are still dominated by studies of harmony, counterpoint, and form.(1) My sense is that this is changing, however, and for very good reasons. Many concepts of rhythm and meter are very accessible and audible—easily grasped by students at all levels. These concepts also have clear implications for performance, making them directly relevant to the practical concerns of performing musicians. Moreover, they are applicable to a wide range of musical styles, including popular music and much non-Western music—more so than conventional theories of harmony and form, which are rather narrowly tailored to common-practice music. For that reason, expanding rhythm and meter’s share of the theory curriculum goes hand in hand with the widespread effort to broaden the stylistic range of music theory teaching. These commendable intentions have been hindered, however, by the lack of an appropriate textbook—one that presents concepts of rhythm and meter in a succinct, easily digestible form, suitable for a broad population of music students.

[3] Matthew Santa’s Hearing Rhythm and Meter (HRAM) is the book we have been waiting for. It brings together the essential ideas from recent scholarship on rhythm and meter and presents them in simple, easily comprehensible terms, with well-chosen illustrative examples. Bullet-point summaries, homework assignments, and lists for further reading are presented at the end of each chapter, and an accompanying score anthology provides full scores of pieces discussed in the book.

[4] In what follows, I provide an overview of the book’s structure and theoretical viewpoint. On the whole, Santa does an admirable job of integrating modern concepts of rhythm and meter into a coherent whole—the “unified theoretical framework” that I spoke of earlier. There are a few areas where I would have done things a bit differently, and where instructors might wish to consider alternative conceptual presentations.

[5] Santa begins by presenting three musical examples whose most natural metrical interpretation conflicts with that indicated by the notation. This is a nice pedagogical strategy, because it conveys the important idea that the meter of a passage is fundamentally something in the mind of the listener rather than in the notation. In discussing these examples, Santa introduces several criteria that affect our metrical hearing, such as sforzandi and changes of harmony. This leads naturally into a discussion of the nature of meter and our perception of it. Here, Santa very much follows the lines laid out by Lerdahl and Jackendoff (1983). Meter is represented as a grid of several levels of evenly spaced “pulses” (actually, just three levels; I will return to this). Our perception of meter is essentially an attempt to find a grid that fits well with events in the music, primarily phenomenal accents. Santa defines a phenomenal accent as one caused by “the beginning of [a] change or group” (9). This definition is not ideal. While a change or group boundary can indicate a strong beat, these are not the only sources of phenomenal accent, or even the most obvious ones; think of a sforzando. (The accent produced by a sforzando is not a result of it being a “change”; if that were the case, a pianissimo chord inserted into a fortissimo passage would seem as accented as a fortissimo chord in a pianissimo passage, which is surely not the case.) Here I prefer Lerdahl and Jackendoff’s definition—a phenomenal accent is something that “gives emphasis or stress to a moment in the musical flow” (1983, 17)—or perhaps (if one finds that circular), something that draws attention to a moment in the music.

[6] I have two other quibbles with Santa’s theoretical framework for meter. First, I find it puzzling that he confines metrical grids to three levels (the tactus and one level above and below). To my mind, a major virtue of metrical grids is that they can be extended beyond the measure to include hypermetrical levels. As Lerdahl and Jackendoff show, hypermeter generally follows the same “well-formedness rules” as lower levels, almost always being duple or (occasionally) triple—though of course it is more susceptible to irregularity than lower levels. Secondly (and relatedly), Santa draws a distinction early in the book between duple and quadruple meter, and returns to this distinction a number of times, sometimes dwelling on it at some length. I question the usefulness of this distinction: Isn’t quadruple meter best regarded simply as a meter with two duple levels above the tactus? Santa does concede that, “for any music identified as being in quadruple meter, a duple interpretation is also possible” (13); I would go further and say that there is hardly any difference between these two interpretations.

[7] In chapters 2 and 3, Santa moves into the topics of hypermeter and phrase rhythm, leaning heavily on the ideas of William Rothstein (1989). Phrase rhythm is defined as “the rhythm created by successive phrase lengths” (23). Phrases are just one level of “melodic grouping structure” (essentially equivalent to Lerdahl and Jackendoff’s “grouping structure”): a hierarchical structure of segments, from sections to periods to phrases to subphrases. Here Santa makes the crucial point that grouping structure and meter are independent—though interacting—structures that can be aligned in different ways: the strongest beat in a phrase may be at the beginning, near the beginning, or at the end. Irregularities in hypermeter and phrase structure can arise in various ways, and can often be understood as deformations of regular (four- or eight-measure) phrases: through overlap (metrical reinterpretation), “expansions” within a phrase, and “extensions” at the end of a phrase. This is all valuable conceptual material, very nicely presented.

[8] Chapter 4 tackles the topic of metrical dissonance, and closely follows the framework developed by Harald Krebs (1999). Metrical dissonance is a situation where two pulse layers are in conflict: “A displacement dissonance is one in which two conflicting (non-aligned) pulse layers are moving at the same speed

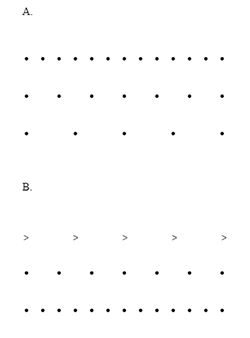

Example 1. (A) A G3/2 grouping dissonance, as represented in HRAM (54). (B) An alternative notation for the same dissonance.

(click to enlarge)

[9] Santa represents metrical dissonances using metrical grids; Example 1A recreates his abstract representation of a G3/2 grouping dissonance (53). (Krebs uses a similar notation—using coffee beans instead of dots—but does not explicitly equate this notation with metrical grids, as Santa does.) This raises a fundamental question, one that I always pose to my students: is a metrical dissonance actually part of the meter, or is it simply a pattern of phenomenal accents conflicting with the meter? I favor the latter view, for two reasons. Experientially, I think it is difficult if not impossible to maintain two meters in mind at once, as Example 1A would seem to imply; indeed, Santa acknowledges this (14–15). In a situation of metrical dissonance, we generally hear one layer as the part of the meter and the other one in conflict with it. And of course (my second reason), this is reflected in Krebs’s (and Santa’s) conceptual presentation as well, and in their terminology: a metrical dissonance involves a “metrical layer” and an “antimetrical layer.” In Example 1A, it is not clear from the notation which is the “antimetrical layer.”

[10] I prefer to notate metrical dissonances by indicating the metrical layer with dots and the antimetrical layer with accent marks. Example 1B shows my notation for the grouping dissonance in Example 1A. (Here I assume that the “2” layer is the metrical layer and the “3” layer is the antimetrical one; the reverse could also occur. I prefer to flip Lerdahl and Jackendoff’s metrical grids vertically, so that the layers that we describe as “lower” are actually lower!) This notation makes explicit the conception of metrical dissonance as a pattern of phenomenal accents that conflicts with the meter. The word pattern is crucial here. A single phenomenal accent conflicting with the meter is not a metrical dissonance, in my view; it is simply a syncopation. Santa is not entirely consistent about this. He defines metrical dissonances as a conflict between two pulse layers (as quoted above), each of which presumably entails multiple pulses; sometimes, however, he seems to accept an isolated long or accented note as a metrical dissonance (e.g. 122–3).(2) One limitation of my approach is that metrical dissonance does not always involve phenomenal accents; it can also be caused by parallelism (pattern repetition), especially in the case of grouping dissonance.

[11] In one respect, I feel that Santa’s treatment of metrical dissonance improves on Krebs’s, and that is with respect to subliminal dissonance. I find Krebs’s presentation of this concept confusing. He writes that subliminal dissonance occurs “when all musical features—accents, groupings, etc.—establish only one interpretive layer, while the context and the metrical notation imply at least one conflicting layer

[12] In contrast to Krebs, Santa sticks consistently to the idea that subliminal dissonance is a conflict between perceived and notated meter. He does urge performers to try to bring out the notated meter, in cases where it is in danger of being perceptually lost. In such situations, he writes:

A performer should. . . honor the composer’s choice of metrical notation even while acknowledging the metrical conflict and do whatever is possible to bring that conflict out for the listener [HRAM, 15].

Importantly, though, Santa does not call this a case of the listener “sensing a subliminal dissonance.” Santa also applies subliminal dissonance—quite appropriately—to the case where the perceived meter at the beginning of a piece conflicts with the notation. I think Santa’s approach here is exactly right; it does have some vexing implications, however. Under this view of subliminal dissonance, it is not really a cognitive phenomenon. There is nothing in our mental representation of a subliminal dissonance, in itself, that marks it as a subliminal dissonance—or indeed, as a dissonance at all. Its “dissonant” character arises only from its relationship to the notated meter. And if we think of metrical dissonance as something in the mind of the listener (as I think we should), it seems odd to define a type of dissonance in terms of the relationship between the perceived meter and the notated one. (The term “subliminal” does not help; a subliminal message in advertising is one that affects the listener at an unconscious level, not one whose effect is completely missed.) Assuming that the notated and perceived meter do coincide at some point, either before or after the subliminal dissonance, subliminal dissonance could also be described simply as a case of metrical shift: our perceived meter shifts from one structure to another, either with regard to period (“subliminal grouping dissonance”) or phase (“subliminal displacement dissonance”).

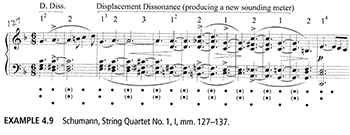

Example 2. (A) Example 4.9 from HRAM (59), showing Schumann’s Quartet Op. 41 No. 1, I, mm. 127–37, with Santa’s metrical analysis. (B) The notation corresponding to Santa’s hearing of the passage (with two additional measures at the beginning).

(click to enlarge and see the rest)

[13] Apart from the term itself, Santa’s presentation and treatment of subliminal dissonance is clear, consistent, and logical. But there is now a substantive musical issue: to what extent should performers try to bring out a hidden notated meter—converting a subliminal dissonance into an indirect one? For that matter, as listeners ourselves, to what extent should we allow the notated meter to influence our perception, as opposed to leaving it entirely up to our ears? The quote from Santa presented earlier suggests that he feels we should “honor” the notated meter. In practice, though, he usually seems to favor the alternative course: let the ears do what they will.

While it is subjective exactly where beat 2 becomes the downbeat of the sounding meter, it is less subjective that it happens somewhere in mm. 131–135. . . Most listeners would probably experience the change somewhere in that span, and once the sounding meter changes, D6+3 no longer sounds like a dissonance, it only looks like one; that is, it becomes a subliminal dissonance, dissonant only in the minds of those holding the score [HRAM, 96].

This suggests that Hearing B is the important one, the one we should focus on. Hearing A is only in the minds of those holding the score—the word “only” suggesting that it is hardly worth bothering with.

[14] In this and other cases, I think Santa is too quick to give up on the notated meter. Let us first consider which of the two hearings in Example 2 is the most musically satisfying—and thus (making an inferential leap that some might question), most likely what the composer intended. Consider first Hearing B. It is not out of the question that Schumann had this metrical interpretation in mind but chose not to notate it, perhaps because it is difficult to read. Musically, though, this metrical interpretation has little to recommend it. Why would Schumann add a confusing extra beat (the

[15] Santa is no doubt right that very few listeners would naturally maintain the notated meter throughout this passage. And in a case such as this, there may be little that performers can do to keep the notated meter alive. (As Santa acknowledges, “Passages that completely suppress the downbeat

[16] Chapters 5 and 6 explore extensions and applications of metrical dissonance. Similarity relations between dissonances are discussed: for example, D2+1 is similar to D4+1 in one respect; in another way, D2+1 is similar to D4+2. “Families” of related metrical dissonances can then be created. Dissonances may be relatively “tight” or “loose” depending on the density of conflicting pulses between the two conflicting layers; with an eighth-note “reference pulse” level, D2+1 (with two conflicting pulses in each quarter-note segment) is tighter than D4+1 (with two conflicting pulses in each half-note segment). A “metrical map” is a way of systematically tracking the metrical dissonances that are used in a piece, and where they are used. This can reflect, for example, the “tightening” process that occurs when a loose metrical dissonance shifts to a relatively tighter one. Another innovation, the “conducting map,” offers a way for people to physically instantiate shifts in sounding meter and hypermeter. Several topics unrelated to metrical dissonance are also discussed in these chapters, such as augmentation/diminution and fragmentation.

[17] Chapter 7 turns to the topic of meter in music with text. Santa begins with the important point that the setting of a line of text is constrained by its natural stress pattern; he also discusses differences in the text-setting conventions of German and Italian vocal music, the former favoring beginning-accented patterns and the latter, end-accented ones. Several analytical discussions follow, illustrating various ways that the construction of a song’s rhythm and meter can be influenced and shaped by its text. Especially nice is Santa’s analysis of Schubert’s “Wandrers Nachtlied”; here he shows how the repeated text phrases and irregular phrase structure depict a meandering, leisurely walk through the countryside. Other analyses show how an especially significant word in the text can be emphasized by various means—by length or phrase expansion (as in Hensel’s “Schwanenlied”) or by placement at the end of a metrical dissonance (as in Wolf’s “Ganymed”).

Example 3. Schumann, Quartet Op. 41 No. 1, I, mm. 88–101

(click to enlarge)

[18] The final chapter brings together the ideas of previous ones, and also connects them to issues of large-scale form. Santa focuses on two pieces: Schumann’s String Quartet Op. 41, No. 1, I (already discussed at several points earlier in the book), and Brahms’s Variations on a Theme by Haydn. The Schumann is in many ways a wonderful choice, and Santa makes many excellent observations about it. He finds interesting connections between the Andante introduction and the exposition of the Allegro, with regard to the trajectories of metrical consonance and dissonance across the two sections; and he perceptively explores the relationship between metrical and tonal instability, finding that the development section of the Allegro often balances metrically unstable passages with tonally stable ones, and vice versa. Formally, the Allegro is a bit problematic (especially for an undergraduate theory class), because the structure of the exposition is rather ambiguous. After beginning in F major, it seems to approach the dominant key area rather conventionally, with a (filled) medial caesura in C major at mm. 99–100 (see Example 3). (Fitting nicely with this view is the fact that the only hypermetrical irregularity at the one-measure level occurs right at the point of modulation, measures 92–95, adding emphasis to the tonal shift; the establishment of the new odd-strong hypermeter at m. 95 is the beginning of the “dominant lock.”) But after the arrival on I of C major in m. 101, the key is established so fleetingly, and then avoided for such a long span of time (mm. 105–24), that one might think this is all part of the transition, with the second theme area arriving only at the return of C major in m. 125; this is in fact Santa’s view.

[19] The analysis of the Brahms/Haydn variations is, likewise, insightful and convincing. Santa shows how Brahms sometimes uses metrical dissonance and pattern repetition to blur or complicate the hypermeter and phrase structure of the theme: for example, in Variation III, creating a 3+3+4 hypermeter that goes against the 5+5 phrase structure, or blurring the same boundary in Variation V with a D3+1 dissonance. Santa also treats these hypermetrical shifts as metrical dissonances in themselves—as conflicts between two high-level pulse layers. This does not seem very helpful to me. I agree with Santa that the theme begins with two 5-measure hypermeasures and then shifts to 4-measure ones; but to call this an “indirect grouping dissonance” (as Santa does) implies that we maintain the 5-measure hypermeter in our minds as we hear the 4-measure phrases, which seems implausible.

[20] I could envision using this book in teaching in a variety of ways: as the text for a one-semester undergraduate course on rhythm and meter (as Santa recommends in the book’s preface); as the text for a large unit on rhythm and meter in one semester of the theory core; or as a text used across multiple semesters of the core, with a rhythm/meter unit in each semester. It could also be very useful in certain graduate-level courses. I regularly teach a course on tonal analysis for doctoral-level performers, and in recent years have devoted it entirely to issues of rhythm and meter; in such a high-level course, it seems more appropriate to read the primary scholarship. I am pleased to see, however, that the basic structure of my course follows that of Santa’s book almost perfectly: First Lerdahl and Jackendoff, then Rothstein, then Krebs (with some other authors added in), then vocal music, and then large-scale analyses that bring everything together. Christopher Hasty’s Meter and Rhythm (1997) offers a valuable alternative viewpoint, but perhaps not for an undergraduate class (where alternative viewpoints can simply be confusing).

[21] For years, I have wished there was a book like this one; I was starting to wonder if I would have to write it myself. I am very glad that someone else has taken up the task, and indeed, has done an outstanding job with it. Hearing Rhythm and Meter is a great resource for those who wish to bring recent theories of rhythm and meter into the classroom. I hope it gains the recognition and widespread use that it deserves.

David Temperley

Eastman School of Music

26 Gibbs St.

Rochester NY 14604

dtemperley@esm.rochester.edu

Works Cited

Cohn, Richard. 2001. “Complex Hemiolas, Ski-Hill Graphs and Metric Spaces.” Music Analysis 20(3): 295–326.

—————. 2015. “Why We Don’t Teach Meter, and Why We Should.” Journal of Music Theory Pedagogy 29: 1–19.

Hasty, Christopher. 1997. Meter as Rhythm. Oxford University Press.

Krebs, Harald. 1999. Fantasy Pieces: Metrical Dissonance in the Music of Robert Schumann. Oxford University Press.

Lerdahl, Fred, and Ray Jackendoff. 1983. A Generative Theory of Tonal Music. MIT Press.

London, Justin. 2004. Hearing in Time: Psychological Aspects of Musical Meter. Oxford University Press.

Mirka, Danuta. 2009. Metric Manipulations in Haydn and Mozart: Chamber Music for Strings, 1787–1791. Oxford University Press.

Rothstein, William. 1989. Phrase Rhythm in Tonal Music. Schirmer.

Schachter, Carl. 1999. Unfoldings: Essays in Schenkerian Theory and Analysis. Oxford University Press.

Temperley, David. 2001. “The Question of Purpose in Music Theory: Description, Suggestion, and Explanation.” Current Musicology 66: 66–85.

Footnotes

1. I have no statistical evidence for this, but it is my impression. Richard Cohn sees a similar imbalance between the teaching of tonality and meter: An outside observer, he suggests, would “find no institution that teaches these two topics with anything close to parity” (2015, 5).

Return to text

2. The term “syncopation” is also used inconsistently; generally Santa uses it to refer to individual events (7, 14, 58), but he also states that “any kind of metrical dissonance is a syncopation” (54), which suggests that the term applies to a pattern of multiple events.

Return to text

3. Santa’s example omits the C4 in the second violin in m. 137. This is an important note, as it makes the cadence (arguably) perfect rather than imperfect.

Return to text

4. Confining our attention to what is easily perceptible by non-musicians does not seem to be a concern in some other branches of music theory—pitch-class set theory, for example.

Return to text

Copyright Statement

Copyright © 2022 by the Society for Music Theory. All rights reserved.

[1] Copyrights for individual items published in Music Theory Online (MTO) are held by their authors. Items appearing in MTO may be saved and stored in electronic or paper form, and may be shared among individuals for purposes of scholarly research or discussion, but may not be republished in any form, electronic or print, without prior, written permission from the author(s), and advance notification of the editors of MTO.

[2] Any redistributed form of items published in MTO must include the following information in a form appropriate to the medium in which the items are to appear:

This item appeared in Music Theory Online in [VOLUME #, ISSUE #] on [DAY/MONTH/YEAR]. It was authored by [FULL NAME, EMAIL ADDRESS], with whose written permission it is reprinted here.

[3] Libraries may archive issues of MTO in electronic or paper form for public access so long as each issue is stored in its entirety, and no access fee is charged. Exceptions to these requirements must be approved in writing by the editors of MTO, who will act in accordance with the decisions of the Society for Music Theory.

This document and all portions thereof are protected by U.S. and international copyright laws. Material contained herein may be copied and/or distributed for research purposes only.

Prepared by Andrew Eason, Editorial Assistant

Number of visits:

3954