Sonic Bridges and Pitch-Based Bonding in Two Songs by Saariaho*

Cecilia Oinas

KEYWORDS: ensemble communication, unison motion, Saariaho, performance research, performativity

ABSTRACT: This article discusses ways in which shared musical lines such as unisons or pitch repetitions can increase and intensify a sense of bonding between performers. Counterpoint-oriented analytical frameworks tend to reduce unisons and unison motion to a single line. By contrast, I propose that unisons’ performative dimension—which I refer to as sonic bridges—foregrounds their importance. Combining analysis with ethnography, I examine unison passages in two songs for piano and voice by Kaija Saariaho, “Parfum de l’instant” from Quatre instants (2002) and “Rauha” from Leinolaulut (2007). This article suggests that Saariaho’s use of sonic bridges not only enables two very different instruments—piano and voice—to compellingly blend, but also strengthens the empathy and bonding between singer and pianist, which further exposes the intimate, multisensory quality of these songs.

DOI: 10.30535/mto.29.3.6

Copyright © 2023 Society for Music Theory

Introduction

In memoriam Kaija Saariaho (1952–2023)

[1] I first encountered Kaija Saariaho’s works for piano and voice when I performed the cycle Quatre instants in 2011. The piano part is quite demanding—it involves multiple crossing lines, concurrent dynamic markings, polyrhythms, and different scales that require unusual fingering choices—and I began practicing it months before meeting with my vocalist collaborator. My part started to make more sense after the first rehearsal with my collaborator, when we heard how our parts connected with one another. To this day, our performance of Quatre instants was one of the most memorable experiences I have had as a chamber pianist. It was only later, after coming to know Saariaho’s music from an analytical perspective, that I realized how extraordinary her writing is in Quatre instants: for instance, the singer and the pianist play numerous times in unison, uncharacteristic for Saariaho’s normally rich, polyphonic textures. But for me and my colleague, the unison moments were much more than a textural or timbral effect: they bridged our sonic path together in ways that exposed us to a very intimate kind of musicking, thus becoming performative tools.(1)

[2] The idea of communication, synchronization, and social bonding in ensemble playing is certainly not a new topic among the fields of music cognition, psychology, pedagogy, or ethnography.(2) A common thread through these studies is that performers communicate with one another through various physical cues such as gaze, body movement, and facial expression (see especially Kawase 2014 or D’Amario and Bailes 2022). Some scholars suggest that synchronized ensemble performance can even lead to merged subjectivity where “one gets absorbed in the music” in such a way that “one can no longer clearly tell whether the sounds being played were one’s own or another’s” (Rabinowitch, Cross, and Burnard 2012, 117–18). As much as these studies deal with musical group interaction, surprisingly little has been written about the repertoire these studies’ participants have been playing—perhaps because the focus is to examine the musicians rather than the music itself.

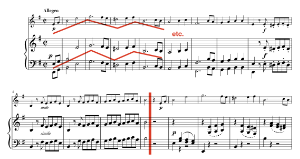

Example 1. Unison in parallel motion: W. A. Mozart’s Sonata for piano and violin in E minor K. 304

(click to enlarge and listen)

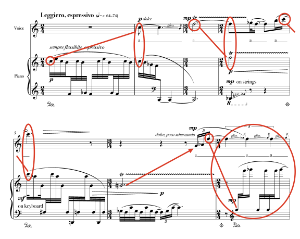

Example 2. Unison passed from one performer to another: Kaija Saariaho’s Luonnon kasvot (2013)

(click to enlarge and listen)

[3] This article builds on the above research on collaborative bonding in chamber music by focusing on a specific musical device: the pitch-class unison, recognizable when performers play the same pitch class, either in unison or in octaves. I concentrate primarily on pitch unisons—where performers play the same pitch—as they provide the clearest examples of “becoming one” in performance. I describe these moments as sonic bridges because they metaphorically “bridge” two or more parts together with the same pitch, even when the instruments are timbrally distinct.(3) Sonic bridges may be further categorized into two types: one involving continuous unison motion, and another where unisons are more fleeting—often passed from one performer (or group of performers) to another. Example 1 illustrates a continuous unison motion between violin and piano in mm. 1–12 of W.A. Mozart’s Sonata in E minor. When speaking about unison lines, examples such as these are the ones that usually come into our mind. However, passing unisons can also create togetherness in performance: Example 2 features fleeting unison moments between singer and pianist in Saariaho’s song “Luonnon kasvot” (“The face of nature”); here the unisons are not continuous, as the annotations show. In both examples, the unisons “bridge” the material of each performer and facilitate intimate interaction between them. My article thus argues that sonic bridges can enhance performers’ senses of bonding, empathy, and togetherness. This resonates with recent pedagogical studies that suggest musical synchronization and musicians’ empathy may involve similar cognitive processes: “Empathy and synchronization rely on the ability to notice, to understand, to internalize, to experience, to connect with and to adequately respond to another’s feelings or another’s rhythm, respectively” (Rabinowitch 2017, 91–92).

[4] Since I value the embodied experience from my own pianistic activities, I primarily focus on sonic bridge examples from repertoire I have come to know as a performer, namely chamber music, particularly Lieder. This is not to downplay examples of sonic bridges in other contexts; I believe, however, that the clearest examples are found in chamber music where each performer becomes a “musical persona,” together taking part in the multiple agencies of musical discourse (Cone 1974, 20–40; Klorman 2016, 20).(4)

[5] The first part of my article investigates sonic bridges in both tonal and non-tonal repertoire, as pitch-based bonding and their performative importance can be found in both repertoires. This will lead to the second part of the article, where I primarily focus on two songs by Kaija Saariaho, “Parfum de l’instant” from Quatre instants (2002) and “Rauha” from Leinolaulut (2007).(5) In both songs, Saariaho uses sonic bridges to create special timbres and delicate intimacy between the performers. Curiously, while the texts of both songs address issues of loneliness and yearning, the constant use of sonic bridges between the singer and the pianist instead suggests an element of togetherness: in “Parfum de l’instant,” nearly all material uniting the singer and the pianist begins on the same pitch. In “Rauha,” the sonic bridges are more overlapping and the sound more blurred because the pianist holds the pedal throughout.(6) The idea of blending resonates with Saariaho’s compositional style in vocal music: according to Pirkko Moisala, “Saariaho is fascinated by the way the voice shares many characteristics with musical instruments, and how it can be blended into the overall orchestral sound” (2009, 87).

[6] In the Saariaho songs, I also propound the ideas of my two professional singer collaborators, Caroline Melzer, and Eeva-Maria Kopp, with whom I have had the privilege to rehearse and discuss the songs from singer’s perspective.(7) My study therefore includes an (auto)ethnographic dimension, which aims to integrate all aspects of my musical knowledge: wissen (knowing that) and können (knowing how) leading to the more holistic kennen (knowing of) (Leong 2019, 16–17). As with many performer-scholars (or scholar-performers), I find my musical identity somewhere in between, described by Daphne Leong as a shared agent (Leong 2019, 31) who can transmit their knowledge and interact with both music theory and performance communities. Therefore, my experience in rehearsing and performing the songs with my collaborators guides my analytical thinking, just like my analytical understanding of the works helps me to find connections and that guide my performances.

1. Background: sonic bridges in music theory and performance

[7] In common practice–era music, pitch-class unison passages were typically used to contrast with polyphonic material. As Janet Levy argues, rather than being only one of the many textural options within the ongoing music, unison is always a special event: “It is striking that when a unison passage is discussed by writers on music, its texture is not merely noted, it is usually characterized

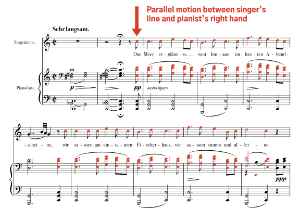

Example 3. Franz Schubert, “Am Meer” from Schwanengesang, mm. 1–10

(click to enlarge and listen)

[8] One rare example of a discussion of performers’ togetherness from a music-theoretical perspective can be found in Edward T. Cone’s analysis (1998) of Franz Schubert’s song “Am Meer” (Example 3). Cone poetically observes the musical bond between singer and pianist through their continuing parallel motion (unisons, sixths, and octaves) and synchronous rhythm in the song. He suggests that, on the one hand, they create “propinquity, as the thoughts of both follow the same path,” but on the other hand, they remain distant because “parallels, after all, never meet” (1998, 121). Cone thus observes the intimate relationship between the pianist and the singer, in which the pianist is not only following the singer’s line through parallel motion but in fact sonically becomes the second protagonist, the unglückliche Weiße of the poem who quietly sits with the protagonist at the seashore.

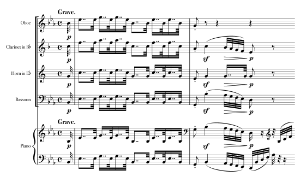

Example 4. Ludwig van Beethoven, Quintet for piano and winds in E-flat major, op. 16, I, opening unison

(click to enlarge and listen)

Example 5. Claude Debussy, En blanc et noir for two pianos, I (Avec emportement), literal unison in mm. 103–8

(click to enlarge and listen)

[9] Although Cone does not address performance issues in this example, it is worth mentioning that for performers, strict parallel lines often create challenges in timing, intonation, and balance—even more so if they are in unison. Consider for instance the tutti octaves in the introductory measures of Ludwig van Beethoven’s Quintet in E-flat major, op. 16, or the passage in Claude Debussy’s En blanc et noir where the two pianos, very unusually, play the exact same tones (Examples 4 and 5). For both examples, any temporal unevenness between performers would disturb the passage’s required uniformity, both sonic and visual.(9) But even if total evenness cannot be achieved for some reason, unison playing enables—perhaps even forces—a close engagement between performers. I thus argue that sonic bridges are potential hermeneutic windows for acquiring the merged subjectivity that Rabinowitch, Cross, and Burnard 2012 describe.

[10] When performers play in unison, they often consider whether the composite sound should blend equally or whether one instrument should be more prominent than the other: for example, in their empirical study, Sven-Amin Lembke, Scott Levine, and Stephen McAdams argue that many professional musicians frequently make a distinction between the leading and the following voice when there are unison and octave blendings.(10) Their study revealed that “followers” often darkened their sound to better blend with the leading part: “Players acting as leaders indeed functioned as a reference toward which followers oriented their playing. In order to achieve blend, followers adjusted towards darker timbres compared to when they performed as leaders” (Lembke, Levine, and McAdams 2017, 160, emphasis original). The aim in darkening one’s sound is to blend in as seamlessly as possible, as if the line would merge into one. This leader-follower discussion surfaced frequently with my singer collaborators. For instance, Caroline wrote the following in one of our written correspondences:

For me personally, the most beautiful examples of the “leader”-relation are operetta arias such as the refrain of [Franz Lehár’s] Vilja-Lied from The Merry Widow. When the solo violin and the singer match in intonation, phrasing and dynamic, I had the impression of really blending into one single tone. I could no longer define which sound was mine and which was the violin’s. What I cherish about this balanced approach is that the voice no longer needs to be enriched or stabilized by a “following” instrument; it can also the supporting party. This opens quite a lot of spaces for interpretation.(11)

She also mentioned that when she is singing in a very high register, any sense of bonding through unisons often materializes after the unison has occurred:

Recently I performed some Uraufführungen [premieres], where I had many long high notes on the same pitch as a string instrument, including quartertone changes. It occurred to me that, in our moment of separation [from the unison], I felt more connectivity to my partner; it is occasionally quite difficult to hear the unison sonic bridge while singing high.(12)

This was also verified by Eeva-Maria, my other collaborator:

In unison moments where I must sing high in my voice, the other instrument’s presence is not necessarily conducive to bridging. Furthermore, depending on the text I am singing in that moment, I may not even hear the other instrument in the moment.(13)

Both singers confirmed that, when concentrating on accurately placing a high pitch, they may be so focused on their own vocal production that they do not pay attention to their bridging partner in the moment, even when acutely aware of the sonic bridge in the score. The above considerations seem to suggest, then, that even when performing together, the sense of bonding may vary from performer to performer, depending on their instrument. I do not see this as a problem, however: just as analysis is a matter of individual perspective, so too is the experience of bonding through unisons. My analyses thus focus on the moments where unison blending is required in the score, and how these moments become potential sites for experiencing sonic bridges.

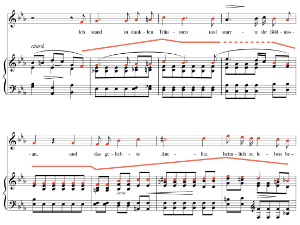

Example 6. Clara Schumann, “Ich Stand in dunklen Träumen,” op. 13, no. 1 (1844), mm. 5–12

(click to enlarge and listen)

Example 7. Franz Schubert, “Der Lindenbaum” from Winterreise, D. 911 (1828), mm. 13–20

(click to enlarge and listen)

2. Two types of sonic bridges

[11] As stated in the introduction, there are two types of unison sonic bridges: one with concurrent unison motion (hereafter called type 1 sonic bridge) and the other involving unisons passed from one instrument to another (hereafter called type 2 sonic bridge). Below I present examples of both types.

[12] Type 1 sonic bridges are commonplace in chamber music. These may be further divided into examples where only some part of the musical material is played in unison, and those where all sounding material is in unison. For instance, in Lieder, a typical example occurs when the singer’s melody is doubled in the upper voice of the pianist’s right hand to give a round overall timbre. Clara Schumann’s “Ich Stand in dunklen Träumen,” op. 13, no. 1 and Franz Schubert’s “Lindenbaum” from Die Winterreise are two representative examples (Examples 6 and 7).(14) Here, the composite texture is not technically a unison, since the piano also provides the harmony. The pianist is supporting the singer’s line and the balancing is usually done in favor for the singer. The piano’s doubling carries more nuance, however: while it supplements the melodic timbre of the singer, it also gives possibility for the pianist to “sing” together with the vocalist. It is not uncommon to see collaborative pianists silently forming the words on their lips, which enables both performers to share the melodic content, one “ohne Worte” and the other “mit Worten.”

Example 8. Robert Schumann, Piano Trio in D minor, op. 63 (1847), I, mm. 7–10

(click to enlarge and listen)

[13] In Classical and Romantic piano trios, there are also many instances in which the piano’s bass line and cello part are in unison, which often causes balancing problems, especially with modern instruments (Example 8). In these cases, the composer is likely aiming towards a special timbre in which the cello is a “sustainer” for the piano’s lesser-vibrating bass part. Yet these types of passages also give the pianist and cellist a chance to bond beneath the melody and accompaniment figures.

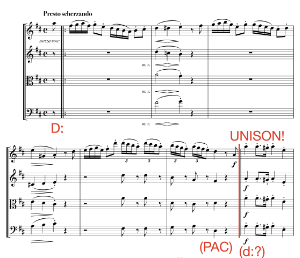

[14] Other examples of type 1 sonic bridges are found where all parts play in unison. The hollow beginning of the second song of Schubert’s Winterreise, “Die Wetterfahne,” is one such example (Example 9). Here, the singer and pianist’s unison line vividly imitates the wind that plays with the weathervane on the top of the protagonist’s beloved’s house. String quartets also include several type 1 sonic bridges, such as Haydn’s String Quartet in D major, op. 20, no. 4, IV (beginning) (Example 10). In this example, the unison in question dramatically interrupts the melodic idea, as if the quartet members suddenly change their mind about the ongoing conversation.

Example 9. Franz Schubert, “Die Wetterfahne” from Winterreise, D. 911 (1828), mm. 1–9 (click to enlarge and listen) | Example 10. Joseph Haydn, String Quartet in D major, op. 20, no. 4 (1772), IV (beginning) (click to enlarge, see the rest, and listen) |

Example 11. Maurice Ravel, Piano Trio in A minor (1914), II (Pantoum), melodic “unison theme” in mm. 13–22

(click to enlarge and listen)

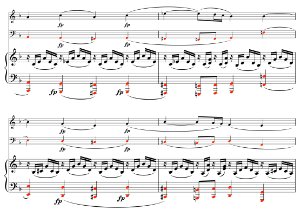

[15] Maurice Ravel’s Piano Trio from 1914 includes several instances of type 1 sonic bridges. They are especially abundant in the second movement (Pantoum), where they primarily emerge around the movement’s second theme (theme b), which is first presented in mm. 13–22, to give contrast for the rapid and rhythmic staccato main theme (theme A) (Example 11). The violin and cello are in strict unison, while the piano also plays the same pitch material within the accompaniment. All three instruments become sonically united when we arrive at the dramatic climax of the movement. In m. 84 the piano and cello begin an E-pedal sonic bridge over theme B in the low register (Example 12); the violin then joins in m. 97 and brings back theme A. Finally, all three instruments take part in the registral ascent and crescendo in unison until they reach the ultimate high point in m. 105, when theme B is presented with all three instruments in an extremely high register and ff dynamics (Example 13).(15) I argue that the sonic bridge moments found in this movement allow the performers to “feel” the pitch-based bonding in the technically difficult passages, providing a fulfilling goal to their surmounting of these difficulties.

Example 12. Ravel, Piano Trio, II, mm. 84–87 (click to enlarge and listen) | Example 13. Ravel, Piano Trio, II, mm. 97–112 (click to enlarge, see the rest, and listen) |

Example 14. Arnold Schoenberg, String Quartet No. 4, op. 37 (1936), III, beginning aggregate in literal unison

(click to enlarge and listen)

[16] Finally, there is yet one distinction to be made in type 1 bridges: that is, a situation when all musicians play unison in the strictest sense in the same register. I call these examples literal unisons, which are a sub-category of type 1. As such, they remain a special case even in unison examples, because it is much rarer that there is only one sounding pitch in one register played by all performers. The beginning unison phrase from third movement of Arnold Schoenberg’s Fourth String Quartet, Op. 37, from 1936 is one such example (Example 14).(16) The beginning (itself an aggregate) and a brief unison episode later in the movement are in sharp contrast with the otherwise polyphonic material. In terms of intonation, balancing, and blending, literal unison types perhaps call even more attention from the performers’ side. But from the perspective of being together, however, I regard all kinds of type 1 unisons as creating tight sonic bonding between performers.

Example 15. Schubert, “Am Meer,” mm. 40–45, type 2 unison bridging at the end of the song

(click to enlarge and listen)

[17] Where type 1 sonic bridges often require performers’ careful attention to synchronization, timing, and balancing, type 2 sonic bridges rather provide timbrally blended moments during ensemble work. In tonal music, type 2 bridges may occur at structural arrivals, such as at the tonic resolution of the closing cadences, which often include resolution to unison or octave with the performers: for instance, in Schubert’s “Am Meer,” the singer and the pianist’s upper line are in unison for the first time in m. 43, which might hint that the two protagonists of the poem have finally found reconciliation (Example 15).

Example 16. Jean Sibelius, “En slända” (Dragonfly), op. 17, no. 5 (1904), mm. 1–10

(click to enlarge, see the rest, and listen)

[18] When type 2 sonic bridges occur more frequently within a composition, however, they facilitate a unique timbral character for the entire work. Example 16 presents the opening measures of Jean Sibelius’s song “En slända” (1904).(17) In the song, the piano part is very sparse throughout, and both singer and pianist perform a considerable amount of their parts without the presence of the other. (As such, this piece could be almost understood a kind of “anti-Lied,” due to the lack of conventional interaction between the duo.) Yet the sonic bridge bondings that occur at the moments of juncture (see annotations in Example 16) place the two performers in close musical, and possibly emotional, proximity.

Example 17. Sibelius, “En slända,” final measures

(click to enlarge and listen)

[19] Considering the poem, which tells a story about the dragonfly that flies in and brings happiness and summer for the protagonist while still wanting to maintain its freedom by evading capture, it seems a deliberate choice by Sibelius that in the final measures, the singer and piano finally locate one another (Example 17). The final two chords present an inverted dominant-tonic resolution (

Example 18. György Kurtág, “Flowers we are

(click to enlarge and listen)

Example 19. Kurtág, “Verés – veszekedés” (Beating – quarrelling) from Játékok VIII, final measures

(click to enlarge and listen)

[20] Four-handed piano music, where two pianists share a single piano, constitute a special case of sonic bridging, considering that unisons played on the same instrument involve a musical and tactile bonding. Despite the apparent inconvenience of playing the same pitch on the same instrument, many composers have explored this possibility, and not always for strictly musical reasons, as Ernst Lubin has written (Lubin 1970, 3). Some composers apply sonic bridges frequently in piano-duo repertoire, such as György Kurtág, whose works often invite performative intimacy that is both intended for performers to create their own personal space and for the audience to voyeuristically witness their pas de deux at the keyboard (see Daub 2014, 17). In “Flowers we are

My above observations are not meant to be universal. But in these examples and others, knowing that (wissen) the unisons carry the potential for bonding among performers enables these performers to know how (können) to further experiment with this potential.

3. “Parfum de l’instant”

[21] After introducing sonic bridges through these examples, I now turn to the two Saariaho songs, in which the imaginative use of sonic bridges becomes a crucial part of the songs’ constitution. I begin with “Parfum de l’instant,” the third song of Quatre instants (2002), and proceed from a general depiction of the song’s character, form, and pitch-based context to unpacking the more personal, embodied experience I had with my collaborators when performing the work.

Example 20. Amin Maalouf’s poem “Parfum de l’instant,” original text and English translation

(click to enlarge)

[22] Like the other songs in the cycle, “Parfum de l’instant” shares many aspects in common with Saariaho’s opera L’amour de loin (2000) in both musical style and text (texts for both works were written by Amin Maalouf). The singer in Quatre instants depicts the character of Clémence from L’amour de loin, the countess of Tripoli who eventually becomes haunted by dreams of her distant lover, troubadour Jaufre Rudel. While the first two songs of Quatre instants are elaborate and fierce in character, the atmosphere of “Parfum de l’instant” is airy, sensual, and mysterious, accompanied by performance instructions such as libero, dolce molto espressivo, and più passionato. The static harmonic language and sustained notes enhance the timeless, even disconnected quality of the song, in which the protagonist is both experiencing and imagining the presence of her loved one when she closes her eyes. Right from the beginning, Saariaho applies the set-class collection (0145), which facilitates sharp-sounding half steps and augmented seconds but also perfect fourths and fifths (that occur in the melodic leaps). A polarity between the piano and voice part also exists, in the sense that the singer’s rhythms are calm and fumbling, while the piano part is filled with rapid yet dreamy and oscillating 32nd-note figurations and repetitions. Example 20 presents the original text and the English translation.

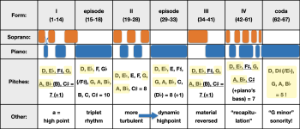

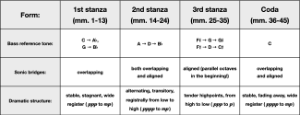

Example 21. Saariaho, “Parfum de l’instant” from Quatre instants (2002), formal outline

(click to enlarge)

[23] The song is divided into four sections with two piano episodes and a coda (Example 21). Rather than adding a second piano episode between the second and third stanzas, Saariaho writes the episode right after the third line of the second stanza, “Nos corps se découvrent.” In the chart in Example 21, I have illustrated in two colors which performer—pianist or soprano—has a more texturally and rhythmically active part. The chart also presents the pitches Saariaho uses in the song. While they change to some extent within each section, the following five pitch classes are maintained through each section: D,

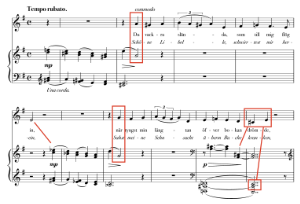

Example 22. Saariaho, “Parfum de l’instant,” mm. 1–12

(click to enlarge and listen)

Example 23. Saariaho, “Parfum de l’instant,” mm. 19–28

(click to enlarge and listen)

[24] Throughout the song, the singer and pianist begin their parts by inheriting the pitch performed by the other—type 2 sonic bridges. This technique creates an enchanted bubble, in which the points of contact arouse auditory, even visceral responses among the performers. Indeed, only type 2 bridges occur in this song, either at the same time, like in the first high point in m. 7, or more in alteration, like in the opening measures (Example 22). Saariaho also differentiates between whether the sonic bridges are brief and alternating (like a relay baton) or whether they are sustained for a longer time and thus create a more articulated timbral blending. In the latter case, Saariaho often blends the soprano’s long, vibrato-sung notes with the pianist’s trill, producing a similar kind of vibrating effect in both parts. This arrangement is especially prominent in section 2, which also includes the most corporeal moments in the poem (“Nos lèvres se frôlent / Nos doigts s’emmelênt / Nos corps se découvrent”) (Example 23). This passionate scene is prolonged with the pianist’s interlude, which is the only time Saariaho asks for a forte dynamic, accompanied with rapid glissandos with both hands and reaching the piano’s highest register.

Example 24. Saariaho, “Parfum de l’instant,” closing measures

(click to enlarge and listen)

[25] Saariaho favors certain pitch-classes in the sonic bridges of “Parfum.” A and D are used, in various registers, throughout the song in this capacity. A5 is also the highest pitch in the soprano part and serves as a local dramatic high point whenever sung. Indeed, as is common in nineteenth-century Italian operas, A and D act a kind of sonorità in the song, thus making them also focal points in creating unity.(22) Finally, A is presented in an entirely new harmonic surrounding in the piano coda, where the pianist’s left hand plays

[26] Caroline and I, unfortunately, have not performed this song together, but she has done so with another pianist. Our discussion was nevertheless a fruitful exchange of ideas. Below is an excerpt of Caroline’s responses, which concerned intonation—something that is not a major concern for the piano but is very much so for almost any other instrument:

You dived a bit into color of timbre, I would maybe further look at the question of intonation, what you mention in the beginning. In comparison to instrumentalists, even singers with perfect pitch can be stressed in matching exactly with the intonation, especially when singer enters first [e.g., in m. 3 of “Parfum”].

Another aspect which interests me a lot is the moment of leaving and returning to the musical line (or note) in common. This occurs especially in mm. 19 and 22–24: the play between consonance and dissonance, the use of intonation, vibrato intensity, and timbre to intensify or weaking the sensation of loneliness or togetherness.

It is interesting that you understand the poem of Maalouf different than I. In my perception, the lovers are close to each other, but the transience of the magic moment, even of the feeling is already anticipated by the poet—which, in my perception, matches with the ongoing leaving and returning to the unison line.(23)

As a pianist, I can never perceive the songs in the same way as a singer, who experiences the music much more physically. Yet pianists also feel the physical tension through their body and by touching the keyboard. For instance, something very extraordinary happens when the music begins in “Parfum de l’instant”: when I hear the singer’s first long note, “moi” on D, I often almost hesitate to enter on the same note; it is like I am entering the singer’s territory. She, however, is very much aware that since I am going to play the same pitch, she needs to intonate it in such a way that a real blending occurs. The moment is therefore intense for both of us, but for different reasons. I also sense a very strong kinesthetic experience when the glissandos begin to take over in m. 7 together with the singer’s high A. As in the poem when the protagonist says “tu es auprès de moi,” the feeling of physical closeness is created with my own instrument and the sonic closeness with the singer via sonic bridges, adding a quasi-Barthesian layer of bonding among body, piano, and soul.(24)

[27] Finally, our divergent readings of the poem raise interesting interpretative questions regarding the relationship between sonic bridge and text. In my reading, the protagonist is the woman who is yearning and reminiscing her lover who is physically not present. In Caroline’s reading, the lovers are also close to each other in the real world. My own reading is probably inspired by the topic of L’amour de loin, in which Clémence and Jaufre Rudel are not physically proximate for most of the opera, and their actual (physical) meeting occurs only at the end of the opera, before Rudel dies. In both readings, however, sonic bridges bind the performers musically, as if both instruments were merged into one.

Video Example 1. Performance of “Parfum de l’instant” by Eeva-Maria Kopp, soprano and Cecilia Oinas, piano (recorded at Sibelius-Academy, Helsinki, June 2022).

(click to watch video)

[28] Eeva-Maria and I created a video of our performance of “Parfum.” (Video Example 1). Despite pandemic-induced limitations on our ability to rehearse together prior to recording, we felt that the preceding mental work and having spent pre-pandemic time together rehearsing different repertoire enabled us to trust each other in suboptimal circumstances. This prior experience working together developed in us a mutual trust that facilitated the exploration of Saariaho’s sonic bridges—something that might not have been possible if we were newly acquainted collaborators.

4. “Rauha”

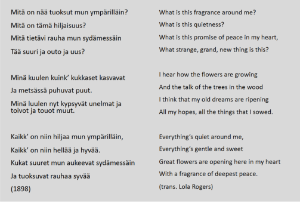

Example 25. Eino Leino’s poem “Rauha” (Peace) 1898, original text and English translation

(click to enlarge)

Example 26. Saariaho, “Rauha” from Leino Songs (2007), opening measures

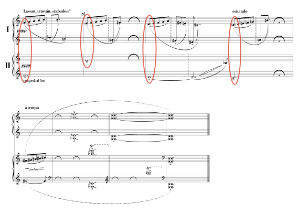

(click to enlarge and listen)

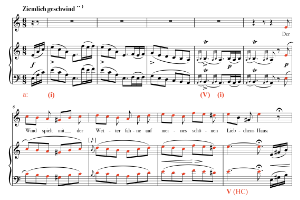

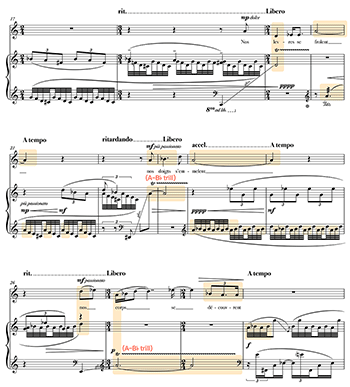

[29] Saariaho’s song “Rauha” offers comparatively more variety in its sonic bridge moments. The text comes from a poem by Eino Leino (1878–1926), one of the most well-known Finnish national Romantic poets from the early twentieth century (Example 25). Leino’s “Rauha” depicts a serene, peaceful moment where the protagonist encounters the scents and quietness around them, both externally (the blossoming nature around) and internally (in their heart). However, “Rauha” can also be understood as something more eternal, which seems to be the case in Saariaho’s setting when she writes “Antonin muistolle” (to the memory of Anton) on the title page (Example 26). The eternal peace is also reflected in the tempo, which remains slow and steady throughout the song, creating a lullaby-like atmosphere with the swaying down-up, up-down gestures in the piano. The sustain pedal is held for the entire song, which enhances the floating sonic landscape and causes new pitches to blend with previous ones, creating a “pitch cloud” rather than any clear harmonies.

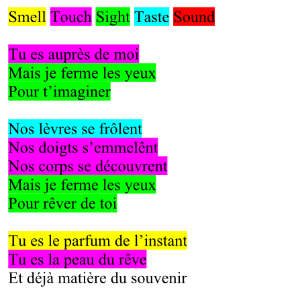

Example 27. Saariaho, “Rauha,” formal layout

(click to enlarge)

[30] The song follows the three stanzas of Leino’s poem, interspersed with piano interludes and a lengthy pianistic coda, as in “Parfum de l’instant” (Example 27). The text is distributed rather spaciously: the stanzas are divided into separate lines for the singer (and the audience) to catch their breath between them. While the metrical structure follows a steady duple meter, the phrase structure is bit more complicated because the sustained bass lasts either five, three, or two measures. In performance, this adds a charming unpredictability regarding when the singer will enter with the next line or stanza.

[31] In the first stanza, the piano register is wide throughout, while the singer’s part is sandwiched between the piano material. The sonic bridges overlap in the first two lines of the first stanza, as though the singer and the pianist are echoing each other’s material. The sonic bridges (type 2) become more united in the third line of the first stanza (mm. 9–10), where the pianist and singer have unisons on the compound downbeats. This is also the first time the word “Rauha” is mentioned in the poem, and Saariaho may have wanted to emphasize the moment with aligned sonic bridges.

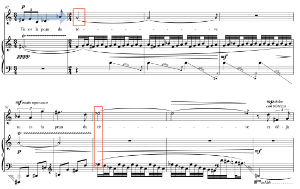

Example 28. Saariaho, “Rauha,” type 1 sonic bridge between pianist’s high register and singer in mm. 26–27

(click to enlarge and listen)

[32] One of the most memorable sonic bridge events is found in the third stanza when the vocal and piano parts become united in a concurrent, type 1 sonic bridge unison motion (Example 28). It is the moment where the “thoughts of both singer and pianist follow the same path,” as described by Cone in his analysis of “Am Meer” (Cone 1998, 121). It is also the first time in which the text begins right on the downbeat, thus making the stanza more poignant and aligned. The protagonist says, “kaikk’ on niin hiljaa mun ympärilläin” (“everything is so quiet around me”). In many performances, the extremely high piano line is played almost as a silver lining to the vocal part. As the singer begins in a high register, marked as piano and dolce, the moment is both delicate and demanding. Even though the singer might not hear the piano’s octave bridge, the pianist can indeed feel togetherness by almost feeling that they are singing the part, something that is touched upon by Benjamin Binder in his research on Innigkeit in Schumann’s Lieder (2007).

Example 29. Saariaho, “Rauha,” mm. 31–35,

(click to enlarge and listen)

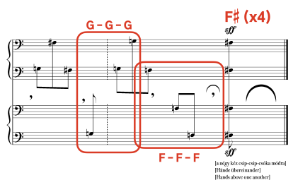

[33] After this type 1 sonic bridge highpoint, the music gradually begins to fade, and for a moment the piano plays only one pitch-class,

Video Example 2. Performance of “Rauha” by Eeva-Maria Kopp, soprano and Cecilia Oinas, piano (recorded at Sibelius-Academy, Helsinki, June 2022)

(click to watch video)

[34] I performed “Rauha” with Eeva-Maria Kopp (Video Example 2). We felt a synergy from our first rehearsal. Performing a song in our own native language, Finnish, with a well-known poem probably guided as towards a certain atmosphere. While “Rauha” is less difficult than “Parfum de l’instant” from a technical perspective, there were challenges here too: even though the parts have common pitches in almost every measure, the singer often needs to sing the new pitch just before the pianist plays it, or vice versa. Indeed, the performance may sound floating and free, so the performers need to be very aware of who is entering on which sixteenth note, triplet, or syncopation. The sustained pedal also means that the singer does not necessarily hear the pitches sufficiently accurately to be able to catch her next pitch from the pianist’s material. In performance, we tried to find “peace” (per the title) in our visual gestures to make the song’s message as clear as possible. In the video, I notice I make the interludes more dramatic and then draw back when Eeva-Maria enters. In the high-point moment discussed earlier, the quiet octave shimmering that bridges our playing does not perhaps seem dramatic from the listener’s perspective. However, the two of us feel more connected than ever at this moment.

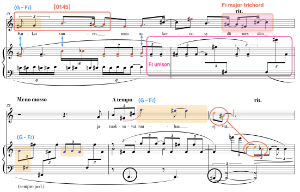

Example 30. Saariaho, “Parfum de l’instant”: the five senses evoked in the text, highlighted with different colors

(click to enlarge and see the rest)

[35] Before closing my analysis, I would like to briefly discuss how Saariaho’s music activates multiple senses and how that also affects the aforementioned songs. According to the composer, “Different senses, shades of color, or textures and tones of light, even fragrances and sounds, of course, blend in my mind. They form a complete world in itself, which calls me to enter into it, and where I can then focus on some details” (Moisala 2009, 55). This is true in “Parfum de l’instant” and “Rauha,” where various senses are evoked in the text (Example 30). In “Rauha,” the first stanza states “Mitä on nää tuoksut mun ympärilläin?” (“What are these fragrances around me?”), which triggers a connection between the sonic output, impression of a scent, and a visual image of a person being first in an indefinite space which gradually begins to reveal itself. Likewise, in “Parfum de l’instant,” the protagonist closes her eyes to dream about the loved one and then says: “Tu es le parfum de l’instant / Tu es la peau du rêve / Et déjà la matière du souvenir” (“You are the perfume of the moment / You are the skin of the dream / And already the material of remembrance”). Perhaps surprisingly, sound is largely absent in the text—indeed, the text makes two references to the absence of sound. Here, too, I feel a strong connection with the themes found in L’amour de loin: Saariaho makes music about silence, about what happens after we close our eyes and let our imagination wonder.

Conclusions

[36] I propose that in these songs, the depiction of various senses may have inspired Saariaho to create a particularly close-knit bond between pianist and soprano by using pitch unisons that consequently become sonic bridges for performers. Seen in this light, it is perhaps appropriate to posit that the unison blendings found in these songs do not simply follow a leader-follower principle, but also aspire to create a special timbral environment in which piano and singer become united—both sonically and performatively. In this sense, timbral blending begets timbral bonding.

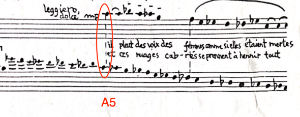

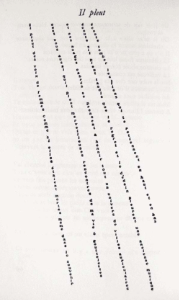

Example 31. Saariaho, “Il pleut” (1986), excerpt from the original score

(click to enlarge)

Example 32. Guillaume Apollinaire’s poem “Il pleut” from Calligrammes: poèmes de la paix et de la guerre, 1913–1916

(click to enlarge and listen)

Example 33. Saariaho’s “Il pleut” performed by Katharine Dain and Sam Armstrong, 7 Mountain Records, 2020.

[37] It may not come as surprise that we find sonic bridges in other songs by Saariaho. The unison blending seems to be one trait Saariaho has been applying from early in her output: for instance, “Il pleut” for soprano and piano (or harp) from 1986 includes both parallel lines and unison moments (Example 31). Setting the poem by Guillaume Apollinaire from his collection Calligrammes: poèmes de la paix et de la guerre, 1913–1916, Saariaho creates a sonic equivalent to Apollinaire’s visual poetry in which the words slowly fall dawn, one after the other like raindrops (Example 32). The pianist/harpist plays a chromatic scale from the highest to the lowest pitch to which the singer smoothly joins in unison (A5) and with same dynamics (mp). After this, the singer and pianist mostly move in parallel intervals. Little by little, their parts become registrally more distant. In the coda, the singer whispers the word “écoute” (“listen”) in her highest sounding pitch, B5, while the piano slowly reaches the bottom A0 (Example 33). The singer and the pianist are intertwined with each other through their synchronized parallel sounds. Neither can exist without the other; this creates a particularly intensive sonic bonding between the two.

[38] Music, like other performing arts, is a mode of communication between human beings. When we do something together, be it singing or dancing, it creates bonds between those who are involved. We crave these kinds of moments to gain courage, power, cohesion, and coalescence. This article suggests that moments when performers are playing unison pitches matched with synchronous rhythm may sometimes become a salient aspect—even a key feature—for an entire work. Saariaho’s use of sonic bridges enables two very different instruments, piano and voice, to blend together in an aurally exciting way. In a more general level, sonic bridges may further enhance the performers’ multisensory experiences, and hence become an important part of the work’s performative design, which I have endeavored to show in this article.

Cecilia Oinas

Sibelius Academy, University of the Arts Helsinki

Pohjoinen Rautatiekatu 9, 00100 Helsinki, Finland

cecilia.oinas@uniarts.fi

Works Cited

Bayley, Amanda. 2011. “Ethnographic Research into Contemporary String Quartet Rehearsal.” In Ethnomusicology Forum 20 (3): 385–411. https://doi.org/10.1080/17411912.2011.645626.

Binder, Benjamin. 2006. “Intimacy, Introversion, and Schumann’s Lieder.” PhD diss., Princeton University.

Bishop, Laura. 2018. “Collaborative Musical Creativity: How Ensembles Coordinate Spontaneity.” Review article in Frontiers in Psychology 9 (July): 1–17. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01285.

Brown, Steven. 2007. “Contagious Heterophony: A New Theory About the Origins of Music.” Musicae Scientiae 11 (1): 3–26. https://doi.org/10.1177/102986490701100101.

Cone, Edward T. 1974. The Composer’s Voice. University of California Press.

—————. 1998. “‘Am Meer’ Reconsidered: Strophic, Binary, or Ternary?” In Schubert Studies, 112–26. Ashgate. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315088389-4.

D’Amario, Sara, and Freya Bailes. 2022. “Ensemble Timing and Synchronization.” In Together in Music, ed. Renee Timmers, Freya Bailes, and Helena Daffern, 139–147. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780198860761.003.0017.

Daub, Adrian. 2014. Four-Handed Monsters: Four-Hand Piano Playing and Nineteenth-Century Culture. Oxford University Press.

Goebl, Werner, and Caroline Palmer. 2009. “Synchronization of Timing and Motion among Performing Musicians.” Music Perception 26 (5): 427–38. https://doi.org/10.1525/mp.2009.26.5.427.

Griffiths, Dai. 1996. “‘So Who Are You?’ Webern’s Op. 3 No. 1.” In Analytical Strategies and Musical Interpretation: Essays on Nineteenth- and Twentieth-Century Music, ed. Craig Ayrey and Mark Everist, 301–14. Cambridge University Press.

Haddon, Elizabeth, and Mark Hutchinson. 2015. “Empathy in Piano Duet Rehearsal and Performance.” Empirical Musicology Review 10 (1–2): 140–53. https://doi.org/10.18061/emr.v10i1-2.4573.

Hunter, Mary. 2014. “Unisons in Haydn’s String Quartets.” HAYDN: Online Journal of the Haydn Society of North America 4 (1). https://remix.berklee.edu/haydn-journal/vol4/iss1/4.

Kawase, Satoshi. 2014. “Importance of Communication Cues in Music Performance According to Performers and Audience.” International Journal of Psychological Studies 6 (2): 49–64. https://doi.org/10.5539/ijps.v6n2p49.

Keller, Peter E., and Mirjam Appel. 2010. “Individual Differences, Auditory Imagery, and the Coordination of Body Movements and Sounds in Musical Ensembles.” Music Perception 28: 27–46. http://dx.doi.org/10.1525/mp.2010.28.1.27.

Klorman, Edward. 2016. Mozart’s Music of Friends: Social Interplay in the Chamber Works. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781316145302.

Lembke, Sven-Amin, Scott Levine, and Stephen McAdams. 2017. “Blending Between Bassoon and Horn Players.” Music Perception 35 (2): 144–64. https://doi.org/10.1525/mp.2017.35.2.144.

Leong, Daphne. 2019. Performing Knowledge: Twentieth-Century Music in Analysis and Performance. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780190653545.001.0001.

Levy, Janet M. 1982. “Texture as a Sign in Classic and early Romantic Music.” Journal of the American Musicological Society 35 (2): 481–531. https://online.ucpress.edu/jams/article-abstract/35/3/482/49237/Texture-as-a-Sign-in-Classic-and-Early-Romantic?redirectedFrom=fulltext.

Lubin, Ernest. 1970. The Piano Duet: A Guide for Pianists. Grossman Publishers.

Moisala, Pirkko. 2009. Kaija Saariaho. University of Illinois Press.

Petrobelli, Pierluigi. 1982. “Towards an Explanation of the Dramatic Structure of Il Trovatore.” Translated by William Drabkin. Music Analysis 1 (2): 129–41. https://doi.org/10.2307/854124.

Pulkkis, Anna. 2014. “Alternatives to Monotonality.” Academic diss., University of the Arts Helsinki, Sibelius Academy.

Raab, Armin. 1991. Die Funktionen der Unisono: dargestellt an den Streichquartetten und Messen von Joseph Haydn. Haag + Herchen.

Rabinowitch, Tal-Chen. 2017. “Synchronisation: A Musical Substrate for Positive Social Interaction and Empathy.” In Music and Empathy, ed. Elaine King and Caroline Waddington, 89–96. 1st ed. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315596587-5.

Rabinowitch, Tal-Chen, Ian Cross, and Pamela Burnard. 2012. “Musical Group Interaction, Intersubjectivity, and Merged Subjectivity.” In Kinesthetic Empathy in Creative and Cultural Practices, ed. Dee Reynolds and Matthew Reason, 109–20. Intellect Books.

Saariaho, Kaija. 2013. “Rauha.” In Mirrors: Works by Kaija Saariaho and Jean Sibelius. Recorded by Katharina Persicke and Pauliina Tukiainen. MBM Mielke Bergfeld Musikproduktion OHG.

—————. 2020. “Parfum de l’instant.” In Regards sur l’infini. Recorded by Katharine Dain and Sam Armstrong. Mountain Records.

—————. 2021. “Rauha.” In Sumun läpi. Recorded by Anu Komsi and Piia Värri. Coloramaestro OY.

—————. 2022. “Rauha” and “Parfum de l’instant.” Recorded by Cecilia Oinas and Eeva-Maria Kopp at Sibelius Academy, Helsinki, 21 June 2022.

Small, Christopher. 1998. Musicking: The Meanings of Performing and Listening. University Press of New England.

Footnotes

* Earlier versions of this article have been presented at the Dialogues: Analysis and Performance Symposium in October 2021 and the SMA Zoom Colloquium series in June 2022. It has benefited from feedback from many people, including Daniel Barolsky, Danijel Detoni, and Jonathan De Souza. I am especially grateful for Benjamin Duinker for useful criticism and numerous suggestions for improvement during the submission stage, Robert Vili Ollila for providing me superb transcriptions for the examples, the anonymous reviewers of Music Theory Online, and finally my two wonderful singer collaborators, Eeva-Maria Kopp and Caroline Melzer, for the inspiring discussions about the Saariaho songs and making music together.

Return to text

1. I use the term “musicking” after Christopher Small (1998). This term encompasses all acts of engagement with music: performance, listening, practicing, analyzing, and composing. In other words, all acts a priori, at present, and a posteriori to performance.

Return to text

2. Prior studies of musical group interaction include Kaller and Appel 2010, Goebl and Palmer 2009, Rabinowitch 2017, Haddon and Hutchinson 2015, Bayley 2011, and Bishop 2018.

Return to text

3. In music that does not necessarily include pitches or melodic lines, such as some percussion repertoire, an analogous concept might be called “rhythmic bridges.” The rhythmic unison moments in works such as Steve Reich’s Clapping Music (1972) would constitute an example of this type of performative bonding.

Return to text

4. Even though I am limiting my research into Western Art music, I do not wish to downplay the importance of unison play in non-Western music or other performing arts such as dance or theatre. Examples include the concept of “Balungan” in Javanese gamelan music and unison singing that happens in an impromptu manner, such as the songs we might hear at sports events. Common to all such examples is that they strengthen the collective by creating a uniformity in which the individual may disappear into the group and, as a result, feel stronger.

Return to text

5. Both song cycles also have an orchestral version by Saariaho. However, as I mentioned in the previous section, I believe sonic bridges are more readily apprehended in a more intimate setting, which is why I will limit my discussion of the songs to the piano and voice version.

Return to text

6. In feedback I have received on earlier drafts of this article, I have been asked to consider the possibility that Saariaho’s composition technique, especially in “Rauha,” could be an example of heterophony, meaning that there is a main melodic line that each performer slightly varies or decorates, like in many folk music styles. However, I do not think that Saariaho’s primary idea here is to create a decorated unison line, but rather to provide moments in which pianist and soprano are sonically united, whether at the same time, in parallel motion, or in a slight asynchrony (for more on heterophony, see Brown 2007).

Return to text

7. Because we are also good friends, I refer them in their first names when they are mentioned in the text.

Return to text

8. Considerations regarding Haydn’s use of unisons are described in Raab 1991.

Return to text

9. By “evenness,” I mean that the unison is perceived as sufficiently synchronized by both performers and listeners. If we would measure the level of synchronization by milliseconds, there are usually slight deviations in timing and pitch accuracy even in examples that are heard as synchronous by human ears (see D’Amario and Bailes 2022).

Return to text

10. Considerations regarding blending and ensemble playing have been made in various music psychological and cognitive studies, such as in Kaller and Appel 2010 and D’Amario and Bailes 2022.

Return to text

11. Caroline Melzer, WhatsApp message to author, June 10, 2022.

Return to text

12. Caroline Melzer, WhatsApp message to author, June 10, 2022.

Return to text

13. Eeva-Maria Kopp, WhatsApp message to author, June 2022.

Return to text

14. Depending on the duo, performers may either try to seamlessly blend or maintain a slight asynchrony (for instance, if the pianist maintains a strict tempo and the singer uses rubato).

Return to text

15. Although the piano part is filled with eighth-note figuration, the sonic bridge line is also present in my opinion.

Return to text

16. Another well-known example of literal unison, although registrally doubled with multiple instruments, is movement VI, “Danse de la fureur, pour les sept trompettes,” from Olivier Messiaen’s Quartet for the End of Time (1940–41).

Return to text

17. The full English translation from the original Swedish poem by Oscar Leventin (1862–1906) can be found at https://oxfordsong.org/song/en-slända. Translations for the other poems mentioned in this article can also be found at https://oxfordsong.org/explore.

Return to text

18. Considerations regarding Sibelius’s songs’ harmonic language, and especially his alternative ways to monotonality, are described in Pulkkis 2014.

Return to text

19. The entire song is tonally very unstable, and the closing progression is in fact the first time a tonic G major chord (albeit in first inversion) occurs, thus making the song either “wandering tonality” or “directed tonality” (Pulkkis 2014).

Return to text

20. However, in the score the unison pitch is marked in square parenthesis [ ] for the primo, which suggests that Kurtág in this instance leaves the decision for the performers whether they want to play the same pitch or not. If they do, there indeed is a very special intimacy between the players here, accompanied with the question of who is leading and who is following.

Return to text

21. As an opposite example, sonic bridges can connect performers when they are physically very distant (more than in a normal ensemble), such as the unison relationship between choir and orchestra in Karlheinz Stockhausen’s “Hoch-Zeiten für Chor” and “Hoch-Zeiten für Orchester” (the final scene from the opera Sonntag aus Licht), which are simultaneously performed in two separate halls.

Return to text

22. Regarding sonoritá in Italian nineteenth-century operas, see Petrobelli 1982.

Return to text

23. Caroline Melzer, WhatsApp message to author, June 10, 2022.

Return to text

24. In his analysis of Anton Webern’s song op. 3, no. 1, Dai Griffiths (1996) creates a fictional quasi-psychoanalytic analytical conversation between the pianist and the singer, centering on the interaction between their pitch collections. In that work, the two musical personae are arguing, even mocking each other, rather than feeling any empathetic sonic bonding. But the main idea is the same: to sonically interact, both via words and pitch collections.

Return to text

Copyright Statement

Copyright © 2023 by the Society for Music Theory. All rights reserved.

[1] Copyrights for individual items published in Music Theory Online (MTO) are held by their authors. Items appearing in MTO may be saved and stored in electronic or paper form, and may be shared among individuals for purposes of scholarly research or discussion, but may not be republished in any form, electronic or print, without prior, written permission from the author(s), and advance notification of the editors of MTO.

[2] Any redistributed form of items published in MTO must include the following information in a form appropriate to the medium in which the items are to appear:

This item appeared in Music Theory Online in [VOLUME #, ISSUE #] on [DAY/MONTH/YEAR]. It was authored by [FULL NAME, EMAIL ADDRESS], with whose written permission it is reprinted here.

[3] Libraries may archive issues of MTO in electronic or paper form for public access so long as each issue is stored in its entirety, and no access fee is charged. Exceptions to these requirements must be approved in writing by the editors of MTO, who will act in accordance with the decisions of the Society for Music Theory.

This document and all portions thereof are protected by U.S. and international copyright laws. Material contained herein may be copied and/or distributed for research purposes only.

Prepared by Amy King, Editorial Assistant

Number of visits:

5070