Review of Kenneth Smith and Vasilis Kallis, eds., Demystifying Scriabin (Boydell Press, 2022)

Jeffrey Scott Yunek

KEYWORDS: Scriabin, lad, form, Russian music, Mystic chord

DOI: 10.30535/mto.29.3.9

Copyright © 2023 Society for Music Theory

[1] In celebration of the 150th anniversary of Scriabin’s birth, Kenneth Smith and Vasilis Kallis have edited a collection that examines the composer’s music from analytical, historical, and performance-based perspectives. As the book’s title suggests, Scriabin and his music have remained shrouded in mystery for over one hundred years. The authors state that the mystery behind Scriabin himself results from his wide array of philosophies and their many contradictory tenets (1).(1) Furthermore, Scriabin claimed to have a rigid compositional system in which “there is not a single extra note” (Sabaneev 2000, 54), but he was evasive about the mechanics of that system.(2) As the editors have shown, this ostensibly fixed method of composition has eluded scholars for decades and has resulted in the development of widely divergent approaches ranging from Russian/Soviet expansions of functional harmony to purely atonal pitch-class set analysis.(3)

[2] The editors have compiled chapters from leading Scriabin scholars, both theorists and musicologists. Beyond demystification, the collection has two goals in mind: (1) to challenge persistent myths regarding Scriabin’s philosophies and musical structures and (2) to open new perspectives on the study of Scriabin and his music. The book succeeds on both counts. Chapters by Simon Morrison and Anna Gawboy, in particular, aptly dispel misconceptions about Scriabin’s music, whereas the remaining chapters explore Scriabin’s beliefs and music by featuring an extensive study of the philosophies that prevailed in late nineteenth-century Russian society and surveying several novel approaches to the interaction of distinct pitch collections in his late music. While each chapter is valuable in its own right, the book’s collective achievement is that it forges connections among the theoretical and historical chapters. These connections, in turn, are likely to inspire future areas of interdisciplinary research.

[3] The editors group the book into three sections that cover historical context (Chapters 1–5), analytical systems (Chapters 6–11), and reception and tradition (Chapters 12–16). This arrangement serves the collection well; but to highlight the aforementioned connections between the theoretical and historical chapters, this review will trace a non-linear path through the work.

[4] The editors’ cowritten chapter (Chapter 14) is an ideal point of departure for exploring the analysis of Scriabin’s music, since it both summarizes previous harmonic approaches and identifies largely overlooked parameters of his music, such as rhythm, meter, and form (Chapters 9, 10, and 15). The authors showcase the various approaches to Scriabin’s harmony through a comprehensive review of the analytical literature going back roughly one hundred years and then situate this literature alongside more recent areas of interest for Scriabin scholars. According to the authors, the ongoing fascination with Scriabin music is due to two factors: (1) the composer claimed to employ a rigorous harmonic system, and (2) he has an unusual status, since he is associated with both tonal-Romantic and post-tonal schools. The authors then identify the divisions in late Scriabin scholarship between those who extend late nineteenth-century functional theories and those who employ pitch-class set analysis. Furthermore, this chapter lays out how these groups of analytical approaches have evolved over time.

Example 1. Andreĭ Bandura’s analysis of Scriabin’s Sonata No. 9 with pentagram figures (23)

(click to enlarge)

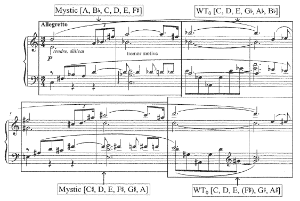

[5] Individual contributions by Vasilis Kallis and Ross Edwards (Chapters 9 and 11) expand on the approaches to Scriabin’s post-tonal harmonic system. Kallis clarifies that Scriabin’s music encompasses far more than his distinctive Mystic chord; it also includes the octatonic, whole-tone, and hexatonic collections, as well as some common variants thereof.(4) In addition, he explains how most of these collections are united by being similarly constructed as locally diatonic collections (Tymoczko 2004, 226–27) that are primarily related to each other by parsimonious transformations. Edwards reinforces Kallis’s claim by diagramming these parsimonious transformations in a series of geometric graphs. These geometric representations are further supported by Morrison’s and Zenkin’s chapters (Chapters 1 and 4, respectively), which note that Scriabin drew geometric figures when sketching his compositions (21–23, 80) and show attempts by Russian theorists to trace these geometric figures within the collections used in his late sonatas. For instance, Example 1 shows Russian theorist Andreĭ Bandura’s analysis of how whole-tone-based symmetrical pentagrams are formed by tracing the pitches in the first four measures of Scriabin’s Sonata No. 9.(5)

[6] The parallels between Vasilis Kallis and Ross Edwards’ analytical theories reflect the similarities found within the broader analytical literature on Scriabin’s music, which primarily differ in how they frame these invariant progressions. One group of scholars (e.g., Callender 1998; Bazayev 2018; Reise 1983) primarily views these progressions as the result of parsimonious voice leading in pitch-class space, whereas another group focuses on maximally invariant transpositions in pitch space (Baker 1986; Cheong 1993; Dernova 1968; Ewell 2005; Perle 1984; Taruskin 1997; Yunek 2017).(6) While reconfirming Scriabin’s use of highly invariant progressions is beneficial, there may be more interest in clarifying whether Scriabin’s system is more parsimonious or transpositional and/or exploring the relevance of these progressions in interpreting Scriabin’s works.

Example 2. Analysis of collections and parsimonious changes in Scriabin’s Op. 69, no. 1, mm. 1–8 by Bazayev (121)

(click to enlarge)

Example 3. Analysis of collections and parsimonious changes in Scriabin’s Op. 69, no. 1, mm. 1–8 by Kallis (146)

(click to enlarge)

[7] An example of the latter is put forth by Inessa Bazayev (Chapter 7), who suggests that chromatic semitonal motion may be a signifier of his well-known injury to his right hand. As with previous harmonic studies, Bazayev notes how semitonal changes often result in alternations between Scriabin’s distinct post-tonal collections, which are readily apparent in both her analysis of Op. 69, no. 1 and Kallis’s in the subsequent chapter (Examples 2 and 3). Bazayev then correlates these semitonal alternations with Scriabin’s life-long injury to his right hand in line with Joseph Straus’s (2011) application of disability theory to Stravinsky’s music. This correlation is apt since such gestures are clearly marked (Hatten 2004, 34–44) in Scriabin’s music through both chromaticism and frequent repetition.

[8] A deeper exploration of Bazayev’s correlation prompts further questions regarding its implications for performance and narrative within Scriabin’s works. Is this idiom simply a musical depiction of his disability, or does it relate to something deeper within his prominent philosophical beliefs? The former claim is suspect because the majority of Bazayev’s examples contain this tremor in the left hand and the first compositions Bazayev shows that feature this idiom are far removed from the time of injury.(7) That being said, Bazayev has clearly identified a significant gesture in Scriabin’s late music that warrants greater study. Perhaps this tremor can be explored through his late philosophical influences that chronologically align with the works mentioned by Bazayev.(8) Although Richard Taruskin (1997, 323–34) has already linked Scriabin’s use of invariance between similar collections to Viacheslav Ivanov’s (2001) philosophical goal of denying the “petty ‘I,’”(9) there is a void in the literature regarding the philosophical import of the use of semitonal alterations to relate different collections—such as the Mystic-chord/whole-tone/octatonic/hexatonic interactions shown by Bazayev, Kallis, and Edwards.(10)

[9] Chapters by Rebecca Mitchell and Simon Nicholls dive deeply into Scriabin’s philosophical beliefs and further situate them within Scriabin’s historical and philosophical context (Chapters 2 and 3). While Scriabin’s views certainly seem strange by modern standards, Mitchell explores how those views could be seen as extensions of major philosophical movements during the Russian Silver Age (1890–1917). She references significant German and Russian philosophies—such as the ideas of Nietzsche and Vladimir Solov’ëv (alt. Solovyov)—and how they were adapted by many Russian thinkers close to Scriabin, such as Ivanov.(11) To underscore that these views were commonly held, Mitchell gives a fascinating account of the protracted debate among contemporary Russians shortly after Scriabin’s death regarding his status as a theurgist. Nicholls’s contribution goes beyond Mitchell’s contextualization of Scriabin’s beliefs by linking these Russian Silver Age philosophies directly to Scriabin’s philosophical writings, program notes, and poems.(12)

[10] Discussions of Russian Silver Age philosophy in this collection are quite extensive, and readers may need prior study to fully understand their significance. For example, Mitchell mentions Ivanov’s concept of Dionysian “ecstatic exultation” (30), which is neither a common philosophical concept nor typically covered in current Scriabin literature. Fully grasping this concept is important because it reveals a connection to a common tenet among Scriabin’s better-known philosophical influences (such as Blavatsky, Nietzsche, Schopenhauer, and Solov’ëv): that one should forsake individuality to achieve greater unity within a broader universal brotherhood (Ivanov 2001, 221). While Mitchell convincingly relates this theory to Ivanov’s unpacking of Scriabin’s theurgy, it is safe to assume that many music scholars are unaware of Ivanov’s philosophy. They would therefore miss the significance of Dionysus in conveying the goal of creating unity through individual sacrifice—a sacrifice that is critical to understanding Scriabin’s status as a theurgist (see 7, 32).(13)

[11] Gawboy (Chapter 12) builds upon the previous chapters by connecting philosophical ideas to the analysis and interpretation of Scriabin’s music. Gawboy begins by dispelling the myth that Scriabin had some neurological form of color-sound synesthesia by contrasting clinical definitions of chromesthesia with our current knowledge of Scriabin’s color-sound associations.(14) She then explains how Scriabin’s color-sound associations likely stem from Helena Blavatsky’s theosophy. For instance, theosophy states that the seven root races are each associated with a specific color, which is reflected in the seven-part formal structure of Scriabin’s Prometheus that is delineated by the notes of the “slow luce” part.(15) However, color-music associations differ significantly between Blavatsky and Prometheus, with only one color being the same (Red = C). As Gawboy shows, Blavatsky’s system is associated with a major scale, whereas Scriabin’s system is associated with a circle of fifths.(16) She also explores the musical and philosophical associations of both the fast and slow luce, as well as the dynamics and extended lighting effects applied to the luce part detailed in Scriabin’s hand-written notes in the so-classed “Parisian score” of Prometheus.(17)

[12] From this perspective, Blavatsky’s philosophy is essential for a deeper understanding of Scriabin’s Prometheus. Given its importance, I find it somewhat surprising that this collection does not include a dedicated chapter on the broader influence of theosophy on Scriabin. Although theosophy certainly has a special relationship with Prometheus due to Scriabin’s direct theosophical comments on the work and the use of important theosophical symbols (e.g., the theosophical seal within Prometheus’s cover art), there is no reason the study of this philosophy’s influence on Scriabin should be limited to this one work. Scattered throughout Demystifying Scriabin are references to the particular importance of theosophy to Scriabin, such as Scriabin’s personal statements that his philosophy closely matched Blavatsky (53), the correlation of his reading of Blavatsky with the onset of his middle period (156), and the association of theosophy with the concept that dominated his last compositional works—the Mystery/Mysterium (61–62). Scriabin’s interest in theosophy is further supported by numerous comments within Sabaneev’s book on Scriabin (2000) and the contents of Scriabin’s preserved library, which contains fifty-two books and journals on theosophy compared to only eight books on the writings of Kant, Nietzsche, Solov’ëv, Schopenhauer, and Ivanov—combined.(18)

[13] Similarly to Gawboy, Simon Morrison’s chapter explores Scriabin’s famous Mystic chord through both theoretical and philosophical lenses (Chapter 1). He immediately dispels misconceptions about the chord, such as the idea that it is fundamentally a quartal collection. Noting the various interpretations of the chord, he explores whether it should be considered a dominant-function chord (McQuere 1983, Dernova 1968, Kholopov 1988, Ewell 2006–2007) that represents eroticism or a stable consonance, as Scriabin reportedly stated to Sabaneev (Sabaneev 2000, 54; see Taruskin 1997, 340–49).

[14] Kostantin Zenkin’s chapter aids in this exploration by examining the origins of functional tonality in Russia and its impact on Scriabin’s training at the Moscow Conservatory (Chapter 4). He spends the majority of the chapter charting the influence of Sergei Taneev (alt. Taneyev), who was evidently the first professor to incorporate Riemannian functional analysis into Russian music pedagogy.(19) Zenkin notes that Taneev’s teaching of function had a major effect on Scriabin, who evidently tried to justify the dominant to subdominant progressions that were forbidden by Taneev through his earliest compositions—suggesting that Scriabin was attempting to stretch the rules of functional tonality from the very beginning of his musical studies.(20) The chapter proceeds to other figures that similarly stretched tonal harmony, such as Tchaikovsky, Liszt, and Rimsky-Korsakov, and to Russian/Soviet function-based systems that attempted to explain Scriabin’s late music, such as Yavorsky’s lad (alt. Iavorskĭ).(21) In Chapter 5, Pavel Shatskiy underscores many of the points made by Zenkin, including the influence of Taneev and Rimsky-Korsakov and the Russian perspective that Scriabin’s works fall into three periods (Kholopov 1988).

[15] The chapters on Russian pedagogy all expose clear gaps in our knowledge of Scriabin’s training, provide significant insights into Scriabin’s works, and reveal multiple avenues for future research. The biggest revelation to me was the potential influence of Konius’s theory of metrotectonism, which was cited by multiple scholars (77, 93–94). Shatskiy only briefly states that the theory is concerned with proportions (93), and it is never applied to an analysis of Scriabin’s music. Nevertheless, it is easy to envision how these proportions might illuminate the enigmatic calculated bars and apparently random numbers in the compositional notebooks for Prometheus (94) and the one-to-one correspondence of tones between the melody and accompaniment documented in his early piano works (74). The assertion of Taneev as a significant teacher ties together many of Scriabin’s pedagogical influences and may reveal new connections among various Russian and Soviet theories on Scriabin’s music. For example, it is easy to trace a line from Taneev to his student Yavorsky—who admired Scriabin’s music (77) and authored an article commemorating Taneev (Yavorsky 1987)—to Yavorsky’s student Varvara Dernova who applied a lad-based approach to Scriabin’s works (1968). This raises a question that might be fruitful for future research: are there insights in Taneev’s teaching of both Scriabin and Yavorsky that informed both Scriabin’s compositional practice and Dernova’s application of Yavorsky’s theory on Scriabin’s works?

[16] Stephen Downes and Ildar Khannanov (Chapters 6 and 15) discuss the construction of Scriabin’s miniature works and how they relate to his compositional influences and Russian/Soviet conceptions of form. Downes begins by reviewing Scriabin’s fixation with miniature works—an extension of his early love of Chopin—and the philosophical tenets that underscore them. He then identifies the formal elements that characterize the miniature: the use of sentences and periods, literal and transposed repetitions, and formal symmetry. Khannanov then explores the importance of these concepts in Russian and Soviet pedagogy, tracing the lineage of these formal concepts from their German sources in Marx and Riemann to their later adaptations by Valentina Kholopova (2001) and Yuri Kholopov.(22) Recalling the importance of functional tonality in Russian pedagogy discussed by Zenkin, he shows how, in the Russian/Soviet understanding, microform and harmonic function are fundamentally linked, and also how functional progressions are correlated with specific emotional affects (289–90).

[17] Antonio Grande and Kenneth Smith (Chapters 9 and 10) explore Scriabin’s larger works with respect to their structure and narrative implications. Building on the work of Susanna Garcia (2000), Grande explores the hermeneutic aspects of Scriabin’s late sonatas through Garcia’s signifiers of flight, light, and many others. Furthermore, he suggests that Scriabin’s use of form is an attempt to control time, which reflects Scriabin’s distinctive use of rubato in playing his own works. Smith shows how the influence of Liszt’s single-movement sonatas is evident in Scriabin’s middle and late piano sonatas (nos. 5–10). Smith uses multi-dimensional diagrams (194–95), modeled after Steven Moortele’s two-dimensional sonata forms (2009), to display the interaction of the main sonata-form sections with the implied progressions of movements (i.e., allegro first movement, slow second movement, optional third movement, and Finale). Noting the penchant of these pieces to rotate among the three octatonic collections (i.e., Oct0,1, Oct1,2, and Oct2,3), Smith suggests that each octatonic collection has a harmonic function (T, S, or D), by which the first collection to appear in a piece is assigned tonic function, the second subdominant function, and the third dominant function.(23) As one might expect, the tonic-function octatonic collection is always the governing octatonic collection at the end of the work, which follows similar insights by Wai-Ling Cheong (1996).

Example 4. Smith’s analysis of Scriabin’s Seventh Sonata, Op. 64, mm. 29–31 (194)

(click to enlarge)

Example 5. Smith’s analysis of Scriabin’s Eighth Sonata, Op. 66, mm. 22–24 (194)

(click to enlarge)

[18] As with many of Scriabin’s later works, one should be careful when analyzing through a predominantly octatonic lens. Whereas Smith’s theory of octatonic rotations works well in Scriabin’s persistently octatonic sixth sonata, it is uncommon for Scriabin’s other works to be as consistently octatonic. For example, the subdominant octatonic area Smith identifies in Scriabin’s seventh sonata (194) features a prominent alternation of octatonic and whole-tone subsets (Example 4), which reflects the collection shifts noted in the previously discussed analytical chapters by Bazayev, Edwards, and Kallis.(24) More prominently, the beginning of the tonic octatonic area in Smith’s analysis of Scriabin’s eighth sonata is not an octatonic subset, but rather a non-centric “harmonic minor” collection, (0134689) (Example 5).(25) This is not a critical analytical error since the next section (i.e., the molto più vivo in m. 52) features a long stretch of purely Oct0,1 material, but it does raise questions about the role of these governing octatonic collections, their interaction with non-octatonic collections, and how these interactions could inform the interpretation of Scriabin’s music.

[19] Chapters by Marina Frolova-Walker and James Kreiling (13 and 16) provide insights about the interpretation and reception of Scriabin’s works. These chapters examine Scriabin’s performance from both Russian/Soviet and English perspectives. As with Grande, Frolova-Walker notes Scriabin’s extensive use of rubato, which Frolova-Walker establishes through a variety of first-hand accounts and piano rolls. She then notes various Russian/Soviet schools of Scriabin interpretation, ranging from the regimented Moscow techniques employed by Sergei Rachmaninov and Scriabin’s wife, Vera Scriabine, to the wildly energetic performances of Vladimir Sofronitsky. Frolova-Walker’s documentation of the Russian/Soviet reactions to these performances are enlightening, and her detailed and impassioned insights about each performer’s take motivate readers to seek out recordings of these competing interpretations. Kreiling (Chapter 16) takes up a similar examination of Scriabin performance and reception that highlights how the reception of Scriabin’s music in the United Kingdom was influenced both by the interpretations of the performers and by the audience’s opinion of Scriabin’s eccentric philosophical views.

[20] In summary, this book provides a rich assortment of analytical and historical approaches that both dispels myths about Scriabin’s music and elucidates his pedagogical and philosophical influences. Regarding the analytical chapters, I especially appreciated how Gawboy grounded her musical analysis in both Scriabin’s hand-written annotations in the Parisian score and a deep study of Scriabin’s primary philosophical influence at the time, Blavatsky’s theosophy. It was also fascinating to get the Russian perspective on Scriabin’s pedagogical training from Zenkin’s chapter, which uncovered several pedagogical influences whose impact on Scriabin’s music invites future exploration. Finally, I found that Mitchell’s explanation of Scriabin’s network of philosophical influences and his standing in Russian society shortly after his death gives one of the most vivid pictures of Scriabin’s historical context to date.

[21] Accordingly, this book is an excellent resource for established Scriabin scholars while also serving as a solid entry point into the study of his music. While additional reading may be helpful in fully understanding the philosophical concepts in the more musicology-focused chapters, no prior reading is required to understand each author’s main thesis. The theory-focused chapters are primarily based on common post-tonal concepts and the authors do a thorough job of referencing the main articles on Scriabin’s late harmonic practice if the reader wants to study further. The performance and reception chapters do not require any prior study and should be stimulating and informative to any listener or aspiring pianist ready to take on Scriabin’s notoriously difficult works.

[22] Although the book certainly achieves its goal of demystifying Scriabin by expanding our knowledge of his philosophical beliefs and reexamining our analytical understanding of his music, I find that the book has also re-mystified Scriabin. That is, the book contains many intersections between historical and analytical approaches that invite various points of inquiry for future study. For example, how did the influential teachings of the counterpoint-driven Taneev—mentioned in four different chapters (4, 5, 14, and 15) but seldom mentioned in prior English scholarship on Scriabin—influence the post-tonal harmony of Scriabin? Furthermore, how does Scriabin’s use of various scale types intersect with the idea that his musical system was an extension of his philosophical beliefs? In short, this book serves as both a robust entryway into the study of Scriabin’s music and a valuable resource for generating new scholarship on this fascinating and pivotal composer.

Jeffrey Scott Yunek

Kennesaw State University

Bailey School of Music

471 Bartow Ave

Kennesaw, GA 30144

jyunek@kennesaw.edu

Works Cited

Arzamanov, Fedor Georgievich. 1984. S.I. Taneev—prepodavatel’ kursa muzykal’nyh form [Sergei Taneev: Teacher of a Course on Musical Form]. Gosudarstvennoe muzykal’noe izdatel’stvo, “Muzyka.”

Baker, James. 1986. The Music of Alexander Scriabin. Yale University Press.

—————. 1997. “Scriabin’s Music: Structure as Prism for Mystical Philosophy.” In Music Theory in Concept and Practice, ed. James M. Baker, David Beach, and Jonathan W. Bernard, 53–96. University of Rochester Press.

Bazayev, Inessa. 2014. “The Expansion of the Concept of Mode in Twentieth-Century Russian Music Theory.” Music Theory Online 20 (3). https://doi.org/10.30535/mto.20.3.6.

—————. 2018. “Scriabin’s Atonal Problem.” Music Theory Online 24 (1). https://doi.org/10.30535/mto.24.1.1.

Belyaev, Viktor. 1927. “‘Analiz moduljacij v sonatah Bethovena’— S. I. Taneeva” [“The Analysis of Modulations in Beethoven’s Sonatas” by S. I. Taneev]. In Russkaia kniga o Betkhovene, ed. Konstantin Alekseevich Kuznetsov, 191–204. Gosudarstvennaia akademiia khudozhestvennikh nauk.

Brown, Malcolm. 1979. “Skriabin and Russian ‘Mystic’ Symbolism.” 19th-Century Music 3 (1): 42–51. https://doi.org/10.2307/3519821.

Butir, L.M. 2001. “Catoire [Katuar], Georgy.” Grove Music Online. Accessed 9 March 2023. https://doi.org/10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.05179.

Callender, Clifton. 1998. “Voice-Leading Parsimony in the Music of Alexander Scriabin.” Journal of Music Theory 42 (2): 219–33. https://doi.org/10.2307/843875.

Carpenter, Ellon. 1983. “The Contributions of Taneev, Catoire, Conus, Garbuzov, Mazel, and Tiulin.” In Russian Theoretical Thought in Music, ed. Gordon McQuere, 253–378. UMI Research Press.

Cheong, Wai-Ling. 1993. “Orthography in Scriabin’s Late Works.” Music Analysis 12 (1): 47–69. https://doi.org/10.2307/854075.

—————. 1996. “Scriabin’s Octatonic Sonata.” Journal of the Royal Musical Association 121 (2): 206–28. https://doi.org/10.1093/jrma/121.2.206.

Cooper, Martin. 1935. “Scriabin’s Mystical Beliefs.” Music & Letters 16 (2): 110–15. https://doi.org/10.1093/ml/XVI.2.110.

Dernova, Varvara. 1968. Garmoniia Skriabina [Scriabin’s Harmony]. Muzyka.

Ewell, Philip. 2005. “Scriabin’s Dominant: The Evolution of a Harmonic Style.” Journal of Schenkerian Studies 1: 118–48.

—————. 2006–2007. “Scriabin and the Harmony of the 20th Century.” Annotated and translated by Yuri Kholopov. Journal of the Scriabin Society of America 11 (1): 12–27.

—————. 2020. “Harmonic Functionalism in Russian Music Theory: A Primer.” Theoria 25: 61–83.

Frank, Semyon. 1950. L. A Solovyov Anthology. Translated by Natalie Duddington. Greenwood Press.

Galeev, Bulat, and Irina Leonidovna Vanechkina. 2001. “Was Scriabin a Synesthete?” Leonardo 34 (4): 357–61. https://doi.org/10.1162/00240940152549357.

Garcia, Susanna. 2000. “Scriabin’s Symbolist Plot Archetype in the Late Sonatas.” 19th-Century Music 23 (3): 273–300. https://doi.org/10.2307/746881.

Gawboy, Anna. 2010. “Alexander Scriabin’s Theurgy in Blue: Esotericism and the Analysis of Prometheus: Poem of Fire, Op. 60.” PhD diss., Yale University.

Hatten, Robert S. 2004. Musical Meaning in Beethoven: Markedness, Correlation, and Interpretation. Indiana University Press.

Ivanov, Viacheslav. 2001. Selected Essays. Edited by Michael Wachtel. Northwestern University Press.

Kholopova, Valentina. 2001. Formy muzykal’nyh proizvedenij [Forms of Musical Works]. Lan’.

Kholopov, Yuri. 1988. Garmonija (Harmony.) Izdatel’stvo Muzyka.

Matlaw, Ralph. 1979. “Scriabin and Russian Symbolism.” Comparative Literature 31 (1): 1–23. https://doi.org/10.2307/1770938.

McQuere, Gordon. 1983. Russian Theoretical Thought in Music. UMI Research Press.

Mitchell, Rebecca. 2016. Nietzsche’s Orphans: Music, Metaphysics, and the Twilight of the Russian Empire. Yale University Press. https://doi.org/10.12987/yale/9780300208894.001.0001.

Moortele, Steven Vande. 2009. Two-Dimensional Sonata Form: Form and Cycle in Single-Movement Instrumental Works by Liszt, Strauss, Schoenberg, and Zemlinsky. Leuven University Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt9qf14r.

Perle, George. 1984. “Scriabin’s Self-Analyses.” Music Analysis 3 (2): 101–22. https://doi.org/10.2307/854313.

Reise, Jay. 1983. “Late Skriabin: Some Principles Behind the Style.” 19th-Century Music 6 (3): 220–31. https://doi.org/10.2307/746587.

Sabaneev, Leonid. 2000 [1916]. Vospominaniya o Scriabine [Memories of Scriabin]. Klassika-XXI.

Scriabin, Aleksandr Nikolayevich. 2018. The Notebooks of Alexander Skryabin. Translated by Simon Nicholls and Michael Pushkin. Oxford University Press.

Sorgner, Stefan Lorenz, and Oliver Fürbeth. 2010. Music in German Philosophy: An Introduction. Translated by Susan H. Gillespie. The University of Chicago Press. https://doi.org/10.7208/chicago/9780226768397.001.0001.

Straus, Joseph N. 2011. Extraordinary Measures: Disability in Music. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199766451.001.0001.

Taruskin, Richard. 1997. “Scriabin and the Superhuman: A Millennial Essay.” In Defining Russia Musically: Historical and Hermeneutical Essays, 308–59. Princeton University Press: https://doi.org/10.1515/9780691219370-013.

Tymoczko, Dmitri. 2004. “Scale Networks and Debussy.” Journal of Music Theory 48 (2): 219–94. https://doi.org/10.1215/00222909-48-2-219.

West, James D. 1970. Russian Symbolism: A Study of Vyacheslav Ivanov and the Russian Symbolist Aesthetic. Methuen.

Yavorsky, Boleslav L. 1987. “Vospominaniya o Sergeyev Ivanoviche Taneyeve” [Reminiscences of Sergey Ivanovich Taneyev]. In Izbrannïve Trudï [Selected Works], compiled by Isaak S. Rabinovich, vol. 2, part 1, 241–348. Sovetskiy kompozitor.

Yunek, Jeffrey Scott. 2017. “(Post-)Tonal Key Relationships in Scriabin’s Late Music.” Music Analysis 36 (3): 384–418. https://doi.org/10.1111/musa.12095.

—————. 2022. “Transformed Desire: Scriabin’s Transition Away from Functional Tonality.” In Musics With and After Tonality, 205–28. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429451713-10.

Footnotes

1. Examples of scholarship on Scriabin’s philosophy include Baker 1997, Brown 1979, Cooper 1935, Garcia 2000, Gawboy 2010, Matlaw 1979, Mitchell 2016, Scriabin 2018, and Taruskin 1997.

Return to text

2. Sabaneev (2000) notes many occasions where Scriabin talked about his theory in fragments. In addition, Sabaneev suggests that Scriabin explained his entire theory to Taneev (2000, 24), which Taneev dismissed without giving specifics.

Return to text

3. A thorough exploration of the analytical literature is discussed in in the editors’ co-authored chapter (269–81).

Return to text

4. It is worth noting that many of these collections have alternative names both within the broader literature and within this book. The Mystic chord is sometimes referred to as the Prometheus chord or as a subset of the acoustic collection (see Edward’s chapter, 204–5), whereas the octatonic collection is often called the tone-semitone scale, the Rimsky-Korsakov scale, or an octatonic variation of the Mystic chord (see Kallis’s use of “mystic chordoct” on 137).

Return to text

5. The creation of these pentagrams, however, requires starting and ending from a missing

Return to text

6. The latter group commonly incorporates parsimonious voice leading to explain transformations between different collection types (e.g., whole tone to Mystic).

Return to text

7. The earliest score Bazayev shows is Scriabin’s Op. 45, No. 1 Feullet d’album, which was composed at age 33 (1904), whereas his injury occurred at age 20 (1891).

Return to text

8. As Kallis notes (156), the onset of Scriabin’s transitional works roughly correlates with his immersion into the spiritual philosophies of Blavatsky.

Return to text

9. Taruskin illustrates how Scriabin’s highly invariant progressions act to subvert tendency-tone resolution, and he connects this denial of tendency-tone resolution to Ivanov’s interpretation of Scriabin’s philosophy, which involves subverting the “petty ‘I.’”

Return to text

10. In this case, I use the term similar to refer to collections related by transposition and/or subset-superset relationships (e.g., two [non-T0] transpositionally related Mystic chords), and different to refer to non-transpositionally/non-subset–superset related collections (e.g., the Mystic chord and octatonic collection).

Return to text

11. A greater understanding of Nietzsche’s impact on Scriabin and others can be found in Mitchell’s recently published book on the subject (2016).

Return to text

12. A full translation of these primary documents was recently published by Nicholls and Pushkin (see Scriabin 2018).

Return to text

13. For further reading on Russian Silver Age philosophy, I recommend books by Frank (1950) and West (1970), which explore the beliefs of Vladimir Solov’ëv and Ivanov, respectively. For the German philosophies that influenced Russian Silver Age thinkers, I recommend Sorgner and Fürbeth (2010), which gives an overview of the basic tenets of Nietzsche (and many other German philosophers) as well as the impact of these ideas on the leading composers of the time.

Return to text

14. My use of the term “neurological” synesthesia follows Gawboy’s terminology in her chapter to distinguish actual perceptual forms of synesthesia (i.e., neurological synesthesia) from artistic or belief-based associations of color and sound. It is worth noting that Scriabin’s lack of conventional synesthesia has been discussed by previous authors (Baker 1997; Galeev and Vanechkina 2001). As Gawboy notes, Scriabin’s lack of neurological synesthesia in no way detracts from the validity of analyzing tone-color correspondences within Scriabin’s works (, 175).

Return to text

15. The luce part in Prometheus is shown on a single staff and features two different voices. The first is called the “slow luce,” which is always sustained over multiple measures and only changes six times over the entire piece. The second is the “fast luce,” which changes approximately every measure and is typically associated with transpositions of the Mystic chord.

Return to text

16. For more on the philosophical and analytical factors that explain Scriabin’s departure from Blavatsky’s system, see Yunek 2022 (216–20).

Return to text

17. A copy of this annotated score can be found on the Bibliotèque nationale de France website in the Gallica collection: https://www.bnf.fr/en/gallica-bnf-digital-library.

Return to text

18. My thanks to the Alexander Scriabin Memorial Museum in Moscow for providing a comprehensive list of the items in Scriabin’s preserved library.

Return to text

19. Ewell (2020) claims that Catorie’s textbook was the first Russian text to explicitly reference Riemannian theory. While this is true, Zenkin’s claim that Taneev initiated the teaching of functional tonality in Moscow is also accurate since a brief glance of Taneev’s writings on harmony and quotes cited by Zenkin in this chapter make it clear that Taneev was teaching functional analysis before Catorie’s book was published.

Return to text

20. This influence is further justified by Butir (2001), who notes that Scriabin began studying with Taneev when he was twelve, that Taneev was instrumental in arranging Scriabin’s early harmony training and getting Scriabin into the conservatory at age sixteen, and that Taneev remained an important mentor and friend until Scriabin’s death. Furthermore, Arzamanov (1984) and Belyaev (1927) note how Scriabin’s score study of Beethoven applied Taneev’s theory of modulatory plans, which is primarily focused on the interaction of subdominant and dominant chords and keys (see Carpenter 1983).

Return to text

21. Note that lad is often translated to “mode” in English. However, many scholars have noted that there are significant differences between lad and standard conceptions of traditional church modes (McQuere 1983; Bazayev 2014). Zenkin gives an improved translation of Yavorsky’s main text, typically translated as The Theory of Modal Rhythm (teóriia ládovogo rítm’), as The Temporal Unfolding of Functional Tonality, which describes the nature of the theory in far clearer terms (77). A well-known exploration of Yavorsky’s theory of lad in Scriabin’s music is given by Dernova (1968).

Return to text

22. Khannanov states that the formal ideas of Kholopov were given in lectures (285).

Return to text

23. The first collection is not always the same octatonic collection between pieces. For example, the sixth sonata begins with Oct1,2, whereas the seventh sonata begins with Oct0,1.

Return to text

24. Example 4 models the interaction of parsimoniously related collections (via indicators) after Kallis (see Example 3).

Return to text

25. Smith analyzes the beginning of the first movement as m. 22 (194), but it is important to note that the beginning of the entire work also does not feature an octatonic collection, but rather Mystic chords (013579) and other non-octatonic/diatonic collections.

Return to text

Copyright Statement

Copyright © 2023 by the Society for Music Theory. All rights reserved.

[1] Copyrights for individual items published in Music Theory Online (MTO) are held by their authors. Items appearing in MTO may be saved and stored in electronic or paper form, and may be shared among individuals for purposes of scholarly research or discussion, but may not be republished in any form, electronic or print, without prior, written permission from the author(s), and advance notification of the editors of MTO.

[2] Any redistributed form of items published in MTO must include the following information in a form appropriate to the medium in which the items are to appear:

This item appeared in Music Theory Online in [VOLUME #, ISSUE #] on [DAY/MONTH/YEAR]. It was authored by [FULL NAME, EMAIL ADDRESS], with whose written permission it is reprinted here.

[3] Libraries may archive issues of MTO in electronic or paper form for public access so long as each issue is stored in its entirety, and no access fee is charged. Exceptions to these requirements must be approved in writing by the editors of MTO, who will act in accordance with the decisions of the Society for Music Theory.

This document and all portions thereof are protected by U.S. and international copyright laws. Material contained herein may be copied and/or distributed for research purposes only.

Prepared by Andrew Eason, Editorial Assistant

Number of visits:

3870