Windows into Beethoven’s Lessons in Bonn: Kirnberger’s Die wahren Grundsätze zum Gebrauch der Harmonie (1773) and Vogler’s Gründe der Kuhrpfälzischen Tonschule in Beyspielen (1776/1778)*

Thomas William Posen

KEYWORDS: Ludwig van Beethoven, Johann Philipp Kirnberger, Georg Joseph Vogler, historically informed pedagogy, thoroughbass, solfeggio, harmony, Elector Sonatas WoO 47, Two Preludes for Piano or Organ, op. 39

ABSTRACT: Beethoven’s lessons in Vienna with Haydn, Albrechtsberger, and Salieri are well known, but considerably less has been written about his earlier studies in Bonn. This article examines what Beethoven may have learned from two treatises that Gustav Nottebohm (1873) connected to Beethoven’s Bonn manuscripts: Johann Philipp Kirnberger’s Die wahren Grundsätze zum Gebrauch der Harmonie (1773) and Georg Joseph Vogler’s Gründe der Kuhrpfälzischen Tonschule in Beyspielen (1776, revised in 1778). I corroborate the evidence that links these treatises to Beethoven, analyze and categorize their contents, and suggest some parallels between materials in these treatises and Beethoven’s Bonn works including his “Elector” piano sonatas (WoO 47; 1783) and his two unusual preludes for piano or organ (op. 39; 1789, published in 1803).

From what we know of Beethoven’s studies in Vienna, several pillars of standard eighteenth-century musical education are missing: the study of solfeggio, thoroughbass, and harmony. This article makes the case that Beethoven encountered this training in Bonn. From Kirnberger’s Grundsätze, he would have learned about the fundamental bass, harmonic function and progression, and the principles of prolongation. In Vogler’s book, he would have encountered solfeggio exercises, common thoroughbass patterns including the Rule of the Octave, invertible sequences, diminution patterns, modulations schemes to every key, the fundamental bass, and more. Although these two treatises were not the only books Beethoven likely studied in Bonn, they offer probable windows into his formative lessons in music theory, improvisation, and composition.

DOI: 10.30535/mto.29.4.5

Copyright © 2023 Society for Music Theory

There is hardly any treatise which could be too learned for me. I have not the slightest pretension to what is properly called erudition. Yet from my childhood I have striven to understand what the better and wiser people of every age were driving at in their works. Shame on an artist who does not consider it his duty to achieve at least as much.(1)

Ludwig van Beethoven, Letter to Breitkopf & Härtel, Leipzig (November 2, 1809)

Introduction

[0.1] Beethoven’s lessons in Vienna with Haydn, Albrechtsberger, and Salieri are well known,(2) but considerably less has been written about his prior studies in Bonn.(3) In this article, I investigate what Beethoven may have learned from two treatises that Gustav Nottebohm (1873) connected to Beethoven’s Bonn manuscripts: Kirnberger’s Die wahren Grundsätze zum Gebrauch der Harmonie (1773, henceforth Grundsätze) and Vogler’s Gründe der Kuhrpfälzischen Tonschule in Beyspielen (1776, revised in 1778).(4) For many reasons, these two treatises would have been ideal for Beethoven to study in Bonn. This article makes the case that they offer windows into his formative lessons in music theory, improvisation, and composition.

[0.2] This article unfolds in three sections. In the first, I summarize what is known of Beethoven’s music lessons in Vienna and Bonn. In the second, I corroborate the evidence Nottebohm used to link Kirnberger’s Grundsätze to Beethoven’s Bonn studies then summarize some of the most important concepts Beethoven would have encountered in this treatise. Beethoven would have learned about the fundamental bass, harmonic function and progression, and what we now call harmonic prolongation among other important topics. Throughout this section I highlight parallels with Kirnberger’s examples and Beethoven’s music, especially passages in his earliest “Elector” sonatas (Kurfürstensonaten, WoO 47), which he composed before the age of 13.

[0.3] In the third and final section, I bolster Nottebohm’s proposal that Beethoven studied Vogler’s Gründe der Kuhrpfälzischen Tonschule in Beyspielen (1776/1778, Mannheim). Nottebohm’s evidence rests on similarities between Beethoven’s two unusual “Preludes Through the Twelve Major Keys for Pianoforte or Organ,” op. 39 (published in 1803 but written before 1789) and circular modulation patterns in Vogler’s treatise. I analyze and categorize Vogler’s patterns and suggest that they represent well the kind of musical thinking that Beethoven would have likely encountered in Bonn.

[0.4] Vogler’s book functions like a didactic and organized zibaldone,(5) a collection of commonplace musical patterns that Vogler could have collected from his studies in Germany and his sojourn in northern Italy under the tutelage of Padre Martini and Francesco Valloti (1773–1775). Vogler’s zibaldone would have been an ideal source for Beethoven to study in Bonn: he would have encountered solfeggio exercises, common thoroughbass patterns including the Rule of the Octave (hereafter “RO”), invertible sequences with suspension chains, diminution patterns, modulation schemes, and much more. Before we explore this content, however, let us turn first to what is known about Beethoven’s lessons in Vienna.(6)

1. Beethoven’s Lessons in Vienna and Bonn

[1.1] Owing largely to the high-profile figures he studied with, Beethoven’s lessons in Vienna put his earlier Bonn studies in a shadow. We must remember, however, that Beethoven was already a young man when he left Bonn. He departed for Vienna at the age of 22 (1792) on a scholarship from Bonn’s Archduke Maximilian Francis to study with Joseph Haydn for six months. Evidently, the plan was for Beethoven to return to Bonn,(7) but this did not come to fruition: Beethoven managed to extend his stay in Vienna indefinitely, beginning with a seven-month extension of his apprenticeship with Haydn (from sometime after November 1772 to sometime before January 19, 1794).

[1.2] Beethoven’s studies with Haydn ended because Haydn had to leave Vienna to conduct his music in England. When Haydn left, he requested that his close friend and theorist-composer Johann Georg Albrechtsberger continue Beethoven’s lessons. This arrangement seems to have suited Beethoven well because he likely met with Albrechtsberger three times a week for over a year (from approximately January 1794–1795).(8) These lessons apparently had a lasting impression on Beethoven: we find traces of Albrechtsberger’s influence in many of his compositions and Beethoven later recommended that students study Albrechtsberger’s treatise, Gründliche Anweisung (1790).(9) Lastly, at the age of 31 (1801), Beethoven pursued advanced studies with Antonio Salieri for about a year that focused on setting text to music (Ronge 2013, 80–81).

[1.3] What did Beethoven study with Haydn and Albrechtsberger in Vienna? According to Nottebohm’s (1873) analysis and Ronge’s (2013) source verification, Beethoven studied counterpoint: species counterpoint in two, three, and four voices, invertible counterpoint, canon, and fugue. The extant sources suggest that Beethoven was taught with methods developed in Fux’s Gradus ad Parnassum and Albrechtsberger’s adaptation thereof.(10) He may have also studied more general elements of composition with Haydn such as musical aesthetics, form, orchestration, and he likely revised pieces that he began in Bonn.(11) Most of these lessons with Haydn must have been conducted orally, however, because there are few surviving manuscripts from them.(12)

[1.4] An astute observer might notice that Beethoven’s Vienna lessons are missing three crucial pillars of standard eighteenth-century training: the study of solfeggio, thoroughbass, and harmony. These omissions should not be surprising, however, because they were typically taught before advanced counterpoint, free composition, and advanced text setting. His studies in Vienna were thus a natural progression that followed his more fundamental musical education in Bonn.(13) In Vienna, he refined his art; in Bonn, he established its foundations.

[1.5] When Beethoven left Bonn as a 22-year-old, he had already composed numerous praised works. Between the ages of 12 and 15, he produced several pieces including the three “Elector” piano sonatas (WoO 47: 1782–83, discussed in Section 2 below), a piano concerto in E-flat major (WoO 4: 1784), three quartets for piano and strings (WoO 36: 1785), and several smaller songs and keyboard pieces.(14) He would have therefore learned the essentials of composition sometime before the age of 13, which would not have been unusual for the time.(15)

[1.6] As a young boy, Ludwig began his studies at the keyboard with his father Johann van Beethoven, the son of the late Bonn Kapellmeister grandfather Ludwig van Beethoven. Johann was clearly determined for his son to progress, because sometime around the age of 8, Johann arranged for his son to take lessons with several teachers including Tobias Friedrich Pfeiffer,(16) who lodged with the Beethoven family from 1779–1780 and the Franciscan friar Willibald Koch,(17) an organist at the local Franciscan Monastery in Bonn. Beethoven also studied with the Bonn court organist Gilles van den Eeden (from ca. 1778–1781), who was a friend of Beethoven’s late grandfather.(18)

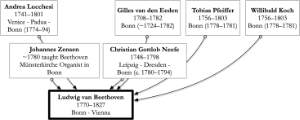

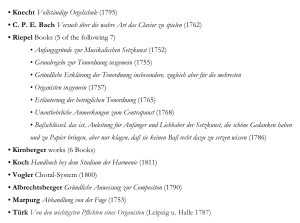

Example 1. Beethoven’s Early Teachers

(click to enlarge)

[1.7] Between the ages of 11 and 12, Beethoven began studying with Christian Gottlob Neefe, who replaced the late Gilles van Eeden as the court organist.(19) In addition to lessons with Neefe, Beethoven likely studied with other musicians in Bonn including the Münsterkirche organist Johannes Zensen(20) and perhaps also with the Bonn Kapellmeister Andrea Lucchesi, although we do not have any direct evidence that proves that Beethoven worked with with the latter. By the age of 13, Beethoven had served two years as an organist for court services, so his lessons must have been sufficient to prepare him for this job.(21) Example 1 visualizes Beethoven’s likely Bonn teachers in a nexus of influence diagram.

[1.8] Although we lack sources that detail fully what Beethoven studied and learned from each teacher, we can construct a rudimentary outline by examining the treatises he likely learned from and by exploring how his teachers were likely taught. Unfortunately, little is known about the musical heritage of Pfeiffer, Zensen, Koch, and Gilles van den Eeden, but we know a fair amount about Neefe and Lucchesi.

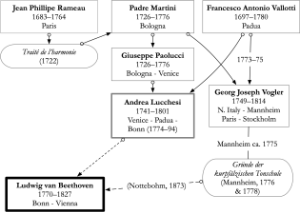

Example 2. Andrea Luchesi’s Nexus of Influence

(click to enlarge)

[1.9] Consider first a sketch of Lucchesi’s nexus of influence (Example 2). Although we do not know if Lucchesi taught Beethoven directly, it is likely that the northern Italian pedagogical tradition that Lucchesi was most familiar with from his studies with Giuseppe Paoluci (a pupil of Padre Martini) and Francesco Valloti would have influenced how composers and keyboardists were taught in Bonn more generally. Lucchesi’s musical heritage suggests a Rameau-influenced, Northern-Italian thoroughbass tradition.(22)

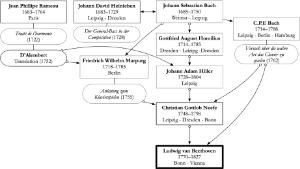

Example 3. Neefe’s Nexus of Influence

(click to enlarge)

[1.10] Now consider Neefe’s nexus of influence (Example 3). In eighteenth-century Germany, it seems that all roads lead back to J.S. Bach: Neefe studied with Johann Adam Hiller (1728–1804), who was a pupil of one of Bach’s direct students, Gottfried August Homilius (1714–1785). As Remeš (2020) proposes, Bach’s teaching was closely related to the thoroughbass method outlined in Johann David Heinichen’s Der General-Bass in der Composition (1728). It stands to reason, therefore, that this thoroughbass tradition, albeit indirectly, influenced Neefe. We also know that Neefe studied C. P. E. Bach’s Versuch über die wahre Art das Clavier zu spielen (1762) and Marpurg’s “Anleitung,” perhaps referring to his Anleitung zum Klavierspielen (1755).(23) Finally, Neefe’s lessons with Hiller suggest strongly that his understanding of harmony would have been influenced by Rameau’s theory of a fundamental bass.(24)

[1.11] With these preliminary sketches of Beethoven’s teachers and their influences, we are now in a better position to explore the link between Beethoven and Kirnberger’s Grundsätze and Vogler’s zibaldone. Although the evidence that links these two specific treatises to Beethoven’s lessons in Bonn is not definitive, these two works introduce principles that correspond well with the music traditions that were circulating in Bonn by some of its most prominent musicians. Thus, while a full account of Beethoven’s lessons in Bonn remains speculative, we can build windows into these studies by examining what he may have learned by studying these treatises.(25) Let us turn now to examine the evidence that links Beethoven to Kirnberger’s Grundsätze in Bonn, a text ghostwritten by one of Kirnberger’s students, Johann Abraham Peter Schulz.(26) (To avoid confusion, I will continue to refer to Kirnberger as the author.)

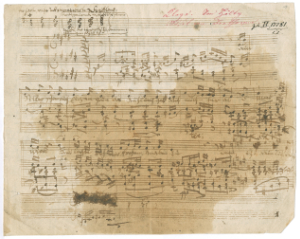

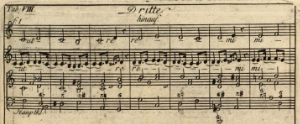

Example 4. Image of the first page of Beethoven’s Bonn manuscript, A 9 WoO 113, “Klage,” Lied für Singstimme und Klavier, Partitur und Skizzen; WoO 87, “Kantate auf den Tod Kaiser Joseph II., Skizzen; Drei- und Vierklang-Studien,” p. 1

(click to enlarge)

2. Kirnberger’s Grundsätze

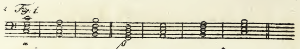

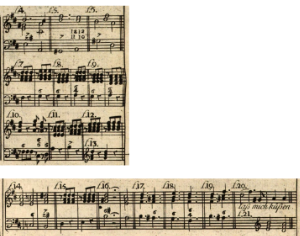

[2.1] On one of his early Bonn music papers (MS Autograph 9, folio 1r; Example 4), Beethoven wrote seven chords with accompanying descriptive text in the top left-hand corner of the recto side of the page (transcribed by Nottebohm in Example 5). Nottebohm (1873, 6) suggests that the handwriting belongs to Beethoven’s earlier years and observes that these chords and text matched a set of chords in Kirnberger’s Grundsätze (Notenbeyspiele, p. 98, fig. 1; compare the chords in Example 4 with Example 5 and Example 6).

Example 5. Nottebohm’s (1873, 6) transcription of Beethoven’s chords (click to enlarge) | Example 6. Kirnberger’s corresponding example in Die wahren Gründsätze zum Gebrauch der Harmonie: Notenbeyspeiele; (Kirnberger 1773, 98) (click to enlarge) |

[2.2] As Nottebohm details, an explanation of the chords that Beethoven copied arises in p. 3, §1, the first paragraph of Kirnberger’s treatise:

All harmony is based on just two fundamental chords. They are the source of all other chords, and everything that is composed in the strict style can be traced to them. These are: [Example 6] the consonant triad (Dreiklang) that is either major (hart), minor (weich), or diminished (vermindert) and the dissonant essential seventh chord, which can be formed in four ways [der dissonirende wesentliche Septimenaccord, der viererlei Zusammensetzungen fähig ist].(27)

Example 7. Petri, Anleitung “Von den besondern Akkorden, welche stets beziffert werden”; (Petri 1782, 227)

(click to enlarge)

One might object to connecting the chords that Beethoven wrote to Kirnberger’s specific treatise because we can find similar chord examples in other contemporaneous treatises, such as Petri’s Anleitung (1782; see Example 7, which was likely inspired by Kirnberger’s treatise). But as Nottebohm observes, the link to Kirnberger’s Grundsätze is compelling because Beethoven’s written text above the chords (e.g., “Der dissonirende wesentliche 7timen-Accord, der viererlei Zusammensezungen fähig ist” over the seventh chords transcribed by Nottebohm in Example 5) matches Kirnberger’s explanatory text verbatim, as do the double bars; Beethoven’s accompanying text differs from descriptions found in other treatises such as Petri’s and Kirnberger’s larger Die Kunst des reinen Satzes in der Musik (1774 and 1776).

[2.3] Given that Beethoven’s chords and accompanying text precisely match their presentation in Kirnberger’s Grundsätze, I support Nottebohm’s proposal that Beethoven copied these chords from this treatise. It is less clear, however, when Beethoven wrote these chords. Although the Bonn manuscript is dated to 1790 on account of the cantata entry at the top of the second verso,(28) additional analytical evidence, discussed below, suggests that Beethoven may have written these chords long before he wrote the rest of the material on the page, perhaps before or while he was writing his “Elector” piano sonatas, which were published in 1783. The chords and text that Beethoven copied (see Example 4, top left-hand corner) are written in a darker ink than the rest of the material on the page: this difference suggests that the “Klage” Lied written below was written at later time.

[2.4] As Nottebohm reminds us, we cannot be certain if Kirnberger’s treatise was used in Beethoven’s lessons.(29) We can safely assume, however, that Beethoven had access to the treatise in Bonn. It is also likely that Beethoven flipped through the book in some capacity, because the explanatory text is at the beginning of the treatise (on page 3) and the written-out chords (shown in Example 6) are situated at the end in the accompanying Notenbeyspiele.

[2.5] Two additional pieces of evidence suggest that Beethoven may have spent more time with the treatise. First, the contents in Kirnberger’s book correspond well with Neefe’s summary of Beethoven’s early lessons. In an oft-quoted passage in Cramer’s Magazin der Musik dated March 2, 1783, Neefe writes:

He [Beethoven] plays the clavier very skillfully and with power, reads at sight very well, and—to put it in a nutshell—he plays chiefly The Well-Tempered Clavichord of Sebastian Bach, which Herr Neefe put into his hands.(30) Whoever knows this collection of preludes and fugues in all the keys—which might also be called the non plus ultra of our art—will know what this means. So far as his duties permitted, Herr Neefe has also given him instruction in thorough-bass. He is now training him in composition and for his encouragement has had nine variations for the pianoforte, written by him on a march—by Ernst Christoph Dressler—engraved at Mannheim. This youthful genius is deserving of help to enable him to travel. He would surely become a second Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart were he to continue as he has begun. (Thayer 1989, 66)

In addition to Neefe’s notes on the Mannheim engraving and the Mozart prophecy—one later reiterated by Count Waldstein(31)—Neefe implies that he taught Beethoven thoroughbass around the same time that Beethoven was playing Bach’s WTC. Kirnberger’s Grundsätze is noteworthy in this regard because it contains two sophisticated analyses of Bach’s Fugue in B minor (WTC, Book I) and the first part of the Prelude in A minor (WTC, Book II).(32) Kirnberger’s treatise would have therefore been an ideal book for Neefe to introduce to Beethoven as he worked through Bach’s WTC. It is evident, moreover, that Neefe thought that Kirnberger’s work was useful for learning composition.(33) Finally, Neefe likely secured the publication of Beethoven’s variations in Mannheim, which suggests a correspondence between Neefe and Mannheim—we shall return to this point when we explore Vogler’s treatise further below.

[2.6] Given Beethoven’s copied chords and the circumstantial evidence that links the text to Neefe’s description of Beethoven’s lessons, let us assume that Beethoven would have spent more time with Kirnberger’s Grundsätze. What would he have learned?

The Fundamental Bass and Harmonic Function

[2.7] If Beethoven ventured beyond Kirnberger’s first paragraph, he would have encountered important concepts such as the fundamental bass (Grundbass), harmonic function and progression, and the principles of harmonic prolongation. Let us examine how these ideas arise in more detail, beginning with the fundamental bass.

Example 8. Kirnberger’s theory of chordal inversions (mentioned by Nottebohm 1873, 6); (Kirnberger 1773, 4–5)

(click to enlarge)

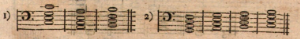

Example 9. Kirnberger’s dominant seventh inversions (Fig. 7–10 as a–d respectively)

(click to enlarge)

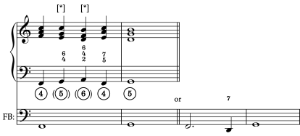

[2.8] On the same page that Beethoven copied the chords and text from, Kirnberger provides the two inversions of the tonic triad and the three inversions of the dominant seventh harmony (Example 8, top system, “Fig. 6”). Kirnberger explains how the different inversions of the dominant seventh chord allow one to change the bass of the same harmony (Example 8, Fig. 7–10; transcribed in Example 9):(34) “These chords that result from inversion [i.e., Example 9b, c, and d] are treated in exactly the same way as their fundamental chords” (§4), namely, as the dominant of the tonic, the most dissonant essential seventh chord, and the tonic.(35) Beethoven would have thus learned about chordal inversion, tonic and dominant harmonic functions, and the fundamental bass. These concepts are important for another idea he would have encountered in all but its name: harmonic prolongation.

Harmonic Prolongation

[2.9] Kirnberger does not explicitly define prolongation as we know it today, but his examples present an advanced understanding of the concept. The treatise devotes an entire section (§18) to durchgehende Accorde (literally “through” chords) that function as Zwischenaccorde (“in-between” or “intermediate” chords).(36) Kirnberger explains:

In harmony there are passing chords (durchgehende Accorde) that are not based on any fundamental harmony. They are to be considered in the same manner as melodic passing (durchgehenden) notes, from which they arise when various voices progress in a passing (durchgehenden) fashion. ([1773] 1979, 192)

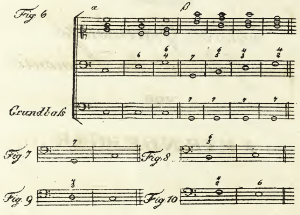

Example 10. Kirnberger’s tonic prolongation introduction; (Kirnberger 1773, 13 Notenbeyspiele Figures 53 and 54)

(click to enlarge)

To illustrate this idea, Kirnberger shows in Example 10a that the intervening D in the bass is “a simple melodic passing tone in relation to the chord above it.” When additional voices are added, as in b), c), and d), an intervening chord is formed. These passing chords, he says, “stand between two fundamental chords that are either the same or at least follow one another very naturally” (Kirnberger [1773] 1979, 192). Kirnberger continues:

Passing chords [durchgehende Accorde] can be further recognized by their unnatural harmonic progressions . . . [that are] unnatural either because some dissonance is left unresolved or because the passing chords, even when they appear as regularly treated fundamental chords, would nevertheless inhibit the natural progression of the fundamental harmony. ([1773] 1979, 192)

To illustrate this principle further, he provides several more examples. Because these examples could have influenced how Beethoven understood harmonic prolongation, let us examine each of them in some detail.(37)

Example 11. Kirnberger’s tonic pedal prolongation; (Kirnberger 1773, 13 Notenbeyspiele Figure 55)

(click to enlarge)

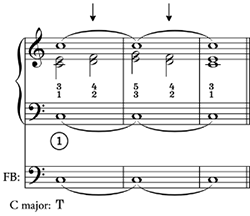

[2.10] In the first of nine examples (Example 11), Kirnberger supplies a tonic pedal with intervening harmonies on beat three of the first two measures (marked with arrows here—asterisks in the original).(38) It is not surprising that his first example is a pedal prolongation because this pattern was usually one of the first that a student would learn to create beginnings and endings of themes while preluding.(39) Beethoven would have thus learned that the intervening harmonies over the pedal do not change the underlying tonic function, as indicated by the fundamental bass.

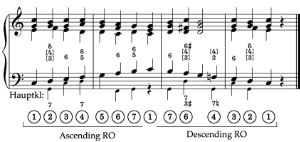

[2.11] In the second example (transcribed in Example 12), Kirnberger provide a slightly more complex version of the prior tonic prolongation. Here, the bass moves stepwise from ① to ③ and ⑤, then back down to ③ with intervening harmonies built on ② and ④. (Parenthesis around the bass scale degrees indicate an in-between, prolonging function). Kirnberger demonstrates here that a tonic remains (i.e., is prolonged) despite the bass changing position from root position (m. 1) to first inversion (m. 4) over the course of four measures.(40) (Kirnberger omits the

Example 12. Kirnberger’s example of passing harmonies in a tonic prolongation; (Kirnberger 1773, 13 Notenbeyspiele Figure 55) (click to enlarge) | Example 13. Modified Kirnberger tonic prolongation without top-voice pedal as a “feigned” or abandoned cadence (click to enlarge) |

Example 14. Kirnberger’s dominant prolongation with passing harmony; (Kirnberger 1773, 13 Notenbeyspiele Figure 55)

(click to enlarge)

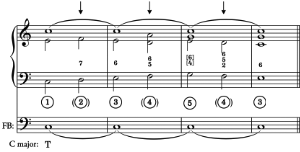

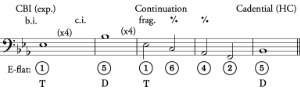

[2.12] After the tonic prolongations, Kirnberger shows how one can prolong the dominant harmony in the same fashion. In Example 14 the bass moves from ⑤ to ⑦ (figured as

Example 15. Kirnberger’s dominant prolongations with passing harmonies; (Kirnberger 1773, 14 Notenbeyspiele Figure 55)

(click to enlarge)

[2.13] In the next example (Example 15a, b, and c), Kirnberger removes the upper tied voice (as he did with the tonic prolongations), presumably to show that the underlying dominant (expressed in the fundamental bass as ⑤) can be prolonged without it, and to demonstrate that the intervening harmony can be realized in different ways. In each instance, the bass similarly moves from ⑤ to ⑦ figured with

[2.14] Parallels with Kirnberger’s tonic and dominant prolongation models abound in Beethoven’s music. Consider, for instance, the beginning of the main theme’s continuation in Beethoven’s Piano Sonata, op. 7 in E-flat major, mm. 5–8 (Example 16).(45) Here, the first two measures (mm. 5–6) prolong the tonic (i.e., the bass moves ①, ②6, ③6; compare with Example 12)(46) and the second two (mm. 7–8) prolong the dominant (i.e., ⑤, ⑥6, ⑦6 in the bass; compare with Example 15b) in essentially the same way as Kirnberger’s examples. For another clear instance, consider the beginning of the subordinate theme in Beethoven’s “Kreutzer” violin sonata (no. 9, op. 47; Example 17). Once again, Beethoven prolongs the tonic with a bass motion that moves from ① to ③6 with an intervening harmony built above ②.

Example 16. Beethoven, Piano Sonata, op. 7, I, mm. 5–8 (click to enlarge) | Example 17. Beethoven, Violin Sonata, op. 47 “Kreutzer,” mm. 92–99 (Subordinate Theme) (click to enlarge) |

[2.15] Of course, it is unlikely that Beethoven turned to Kirnberger’s treatise when he wrote these passages. Rather, I highlight these two examples to suggest that Beethoven would have understood that the intervening passing harmonies function as subordinate to a single prolonged harmony. In other words, it seems sensible to ascribe to Joel Lester’s (2007, 146) position on the relationship between theory and composition, namely, that “musicians understood what they were doing or—to put it in another way—that musicians did not have to await posthumous theories and the posthumous development of analytical tools in order to understand what it was they had been doing.”(47) Although the neologism “prolongation” appears after Beethoven’s time, it is likely that he understood the principles behind this concept from an early age. Our modern harmonic analyses of the passing harmonies in these examples may correspond to how Beethoven could have understood them.(48)

Example 18. Kirnberger’s dominant and tonic prolongations in the minor mode; (Kirnberger 1773, 14 Notenbeyspiele Figure 55)

(click to enlarge)

[2.16] Let us return to the Grundsätze. In his next set of prolongation examples (Example 18), Kirnberger shows several additional ways to prolong the dominant and tonic harmonies in the minor mode (specifically in A minor). In Example 18a, the bass arpeggiates a dominant harmony beginning on the leading tone (i.e., EMm7 as ⑦, ②, ④

Example 19. Kirnberger’s prolongation of ➃ in the bass with double prolonging harmonies; (Kirnberger 1773, 15 Notenbeyspiele Figure 58)

(click to enlarge)

[2.17] Kirnberger provides two final examples that demonstrate a sophisticated understanding of prolongation that extends the principle of harmonic embellishment. Consider the first example (Example 19). Kirnberger explains: “When a chord is definitely expected in the context of a piece, as, for example at cadences, greater harmonists use far stranger intermediate chords (Zwischenaccorde) to make the expected harmony all the more striking. However, these intermediate chords are all passing (durchgehend sind).”(50) In other words, the harmonies built above ⑤ and ⑥ are both intermediary to the underlying ④ to ⑤ motion for the (implied) half cadence as indicated in the fundamental bass.(51) This example demonstrates that a harmony can change inversion and be prolonged with multiple intermediary harmonies.

[2.18] Kirnberger’s alternate fundamental bass (to the right of Example 19) suggests a sensitive analyst: he places the fundamental bass of the fourth harmony a third below and figures it with 7 to imply a DMm7 dominant harmony. Presumably, he writes this alternative analysis to align the example with his principles of harmonic progression (influenced by Rameau’s double-emploi), which we will turn to next after one final prolongation example.

Example 20. Kirnberger’s hypermetric prolongation of tonic harmony; (Kirnberger 1773, 15 Notenbeyspiele Figure 59)

(click to enlarge)

[2.19] Kirnberger supplies one more example that demonstrates what we would today call a hypermetric prolongation (Example 20). Consider Kirnberger’s explanation in full:

When considering the weak beat of the measure with regard to passing chords, it remains to be noted that here we are talking in general about the strong and weak parts of the metric unit. In alla breve time, or when the unit is fairly long, passing chords can even fall on the downbeat of a measure, as in [Example 20 at the asterisk]. In this case the second measure is the weak half of a rhythmic unit, just as the second half of a measure is its weak part. ([1773] 1979, 195, §18)

In present-day terminology, the second measure of Kirnberger’s example brings an intermediary harmony that prolongs, at the hypermetric level, the underlying tonic harmony expressed in the first and third measures. Although Kirnberger does not use the word “hypermeter,”(52) Beethoven would have understood elements of this concept in all but name.

[2.20] To summarize, if Beethoven studied the first part of Kirnberger’s Grundsätze in Bonn, he would have developed an advanced understanding of the fundamental bass, and what we today call harmonic function and prolongation at local and hypermetric levels.

Harmonic Progression and Beethoven’s “Elector” Piano Sonatas (WoO 47)

[2.21] Let us turn now to Kirnberger’s theory of harmonic progression by fundamental bass in the Grundsätze, which differs somewhat from the rules given in his larger Die Kunst des reinen Satzes (henceforth, Kunst). Beach ([1773] 1979, 165) suggests that these differences arise because Schulz, the ghost-writer of the Grundsätze, integrated some of the ideas he learned from studying Rameau’s Traité de l’harmonie (1722) with a gloss of Kirnberger’s Kunst.(53)

Example 21. Kirnberger’s most common fundamental bass progressions; (Kirnberger 1773, 20 Notenbeyspiele Figure 85)

(click to enlarge)

[2.22] In §22 of the Grundsätze, Kirnberger explains that a complete explanation of harmonic progression “would be too detailed for our purpose” so he sketches a shorter outline for beginners that contains only the “most natural and most common progressions of the fundamental bass.”(54) These progressions include: “those in fourths and fifths [Example 21]; secondly those in sixths or descending thirds [Example 22]; thirdly, those in seconds, but seldom different from the situation shown in [Example 23].”

Example 22. Kirnberger’s “secondarily” common fundamental bass progression by thirds (or ascending inverted sixths) [Arabic scale-degrees added] (Kirnberger 1773, 20 Notenbeyspiele Figure 86) (click to enlarge) | Example 23. Kirnberger’s typical stepwise fundamental bass progression (indicated by +); (Kirnberger 1773, 20 Notenbeyspiele Figure 87). (click to enlarge) |

[2.23] The first two progressions (Example 21) demonstrate descending sequences that start and end on a root-position tonic. The third progression (Example 22) exemplifies a root-position, descending thirds progression, and the last (Example 23) is intended to show an exception to otherwise forbidden stepwise movement in the fundamental bass. Of the four progression types, the third (Example 22) could be used to build a more conventional theme with a beginning, middle, and end; the first two sequences (Example 21) are better suited for medial formal functions such as a transition and or a development core; and the last (Example 23) is appropriate for building an ending, cadential function.(55)

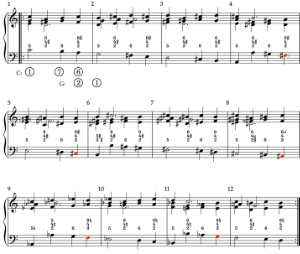

Example 24. Beethoven, Piano Sonata in E-flat major, I, mm. 1–10 (WoO 47, 1783)

(click to enlarge)

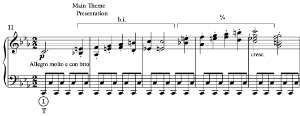

[2.24] Although the root-position, descending thirds progression (Example 22) could be used to build a theme, it is seldom found in Beethoven’s music. We more commonly find stepwise bass motion with chordal inversions.(56) It is therefore notable that Kirnberger’s root-position, descending thirds model matches the structure of two of the main themes found in Beethoven’s early “Elector” piano sonatas (WoO 47; 1783).

[2.25] Consider the main theme of the E-flat major “Elector” sonata (Example 24). Here, Beethoven starts the theme with an eight-measure initiating expanded compound basic idea with prolonged tonic (mm. 1–4, expressed with ①

Example 25. Bass model of Beethoven, Piano Sonata in E-flat major, I, mm. 1–10 (WoO 47, 1783) (click to enlarge) | Example 26. Bass model of Beethoven, Piano Sonata in F minor, I, mm. 10–17 (WoO 47, 1783) (click to enlarge) |

Example 27. Beethoven, Piano Sonata in F minor, I, mm. 10–17 (WoO 47, 1783)

(click to enlarge)

Example 28. Beethoven, Piano Sonata in C minor, op. 13, I, mm. 11–15

(click to enlarge)

[2.26] Consider now his F minor “Elector” sonata. Once again, Beethoven builds the main theme with a similar descending thirds structure in octaves (Example 26).(59) In more detail (see Example 27), the theme starts with a compressed, two measure presentation (mm. 11–12) that articulates tonic harmony (i.e., ①;(60) Beethoven seems to have reworked this presentation from the Elector sonata to become the main theme of his later piano sonata, op. 13, I, the “Pathetique” shown in Example 28).(61) Thereafter, a continuation (Example 27, mm. 13–15) follows with the same, root-position, descending thirds pattern (observe the bass scale degrees ①, ⑥, and ④).

[2.27] In contrast to E-flat sonata’s main theme, which moves to a half-cadence from ② to ⑤, the pattern in this F minor sonata stops at ④, which moves directly to ⑤. It is evident, nonetheless, that the descending third, root-position pattern underlying both main themes is strikingly similar to Kirnberger’s model. (Compare the progressions of Beethoven’s two “Elector” themes in Example 26 and Example 25 with Kirnberger’s in Example 22.)

[2.28] Given that Kirnberger’s root-position, descending thirds pattern is seldom found in the main themes of Beethoven’s later works, it is remarkable that it appears so prominently in the main themes of two of the composer’s earliest pieces. Recall that this descending thirds progression is the only pattern that Kirnberger provides that can express a more conventional theme. Perhaps Neefe advised Beethoven to write some themes inspired by Kirnberger’s model.

[2.29] To summarize, Beethoven would have learned three important music theoretical ideas from Kirnberger’s Grundsätze: (1) the fundamental bass and inversional harmonic equivalence, (2) a rich understanding of what we today call prolongation, and (3) a notion of harmonic progression by fundamental bass. These ideas appear to inform music he wrote throughout his life, including his earliest works completed in Bonn.

3. Vogler’s Kürpfälzische Tonschule

[3.1] Now that we have explored some of the important concepts that Beethoven would have learned from studying Kirnberger’s Grundsätze, let us turn to Vogler’s Kuhrpfälzische Tonschule (1776/1778). Vogler’s didactic work would have been another great source for Beethoven to study in Bonn and was highly regarded in its time.

[3.2] One of the most prominent musicians that was interested in purchasing a copy of Vogler’s book was Leopold Mozart. In a letter to his wife and son (Amadeus)—who was visiting Mannheim where Vogler was recently hired as the Vice-Kapellmeister(62)—Leopold wrote enthusiastically on June 11, 1778:

I hear that Vogler at Mannheim has brought out a book [Kurpfälzische Tonschule], which the Government of the Palatinate has prescribed for the use of all clavier teachers in the country, both for singing and composition [Leopold's emphasis]. I must see this book and have already ordered it. There must be some sound stuff in it, for he could copy the clavier method from [C. P. E.] Bach’s book,(63) the outlines of singing method from Tosi and Agricola, and rules for composition and harmony from Fux, Riepel, Marpurg, Mattheson, Spiess, Scheibe, d’Alembert, Rameau and a host of others, and then boil them down into a shorter system, such as I have long had in mind. Thus I am anxious to see whether his ideas accord with mine. You ought to have the book, for such works are useful when giving lessons. As a teacher one is led by experience to adopt certain good methods of dealing with this or that problem, and these good methods do not all come at once. (Anderson 1989, 548–49)

Leopold hypothesizes that Vogler’s treatise would be useful for composition lessons because it could synthesize numerous treatises into a practical, compact work. In addition, he mentions that it was prescribed for use by all teachers by the Government of the Palatinate. It seems likely, therefore, that it was known by music teachers in Bonn.(64)

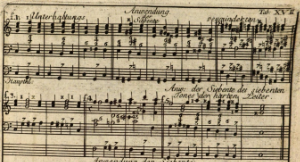

[3.3] As Leopold predicted, Vogler’s thirty-page book functions like a highly organized and didactic zibaldone—a notebook packed with useful musical patterns that Vogler could have assembled from his early studies in Germany and his training with Martini and Valloti in Bologna and Padua, Italy. It includes numerous patterns for the aspiring composer and improviser, such as scales notated and fingered in every key, diminution patterns, the RO, sequences, solfeggio patterns, cadential embellishments, modulation schemas to every key, and much more. In addition, most of Vogler’s examples include the fundamental bass notated in small noteheads on the same staff as the basso continuo. This feature is important, because it marries well with Kirnberger’s treatises, which Beethoven seems to have studied in Bonn, and the concept would have been adopted by prominent Bonn musicians like Neefe and Lucchesi (see Example 2 and Example 3). Before we explore Vogler’s book in greater detail, however, let us examine the evidence that Nottebohm used to link this source to Beethoven’s Bonn studies.

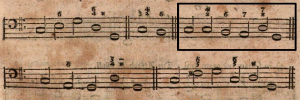

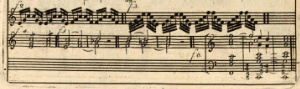

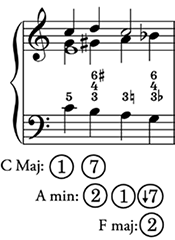

Example 29. Beethoven, op. 39, no. 2,

(click to enlarge)

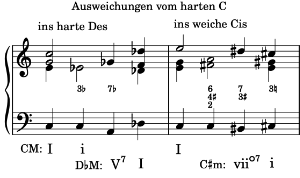

Beethoven’s Two Curious Preludes, Op. 39 and Vogler’s Kürpfälzische Tonschule

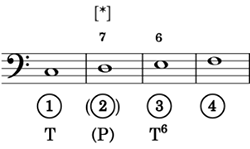

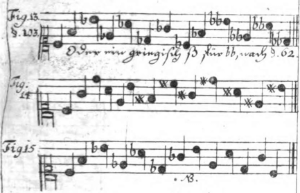

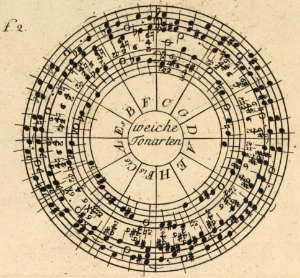

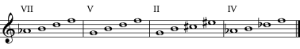

[3.4] Sometime before 1789, while he was still in Bonn, Beethoven composed two curious short preludes—the so-called preludes circulaires—that were later published in 1803 as op. 39.(65) These two pieces are unusual because they both rapidly modulate through all the twelve major keys following the circle of fifths (from C to

Example 30. Beethoven, op. 39, no. 2 Modulation Scheme

(click to enlarge)

[3.5] A glance at the second prelude (Example 29) reveals that almost all the modulations follow the same thoroughbass pattern (Example 30). It does seem, therefore, that this prelude began as a modulation exercise. Still, Beethoven organizes the material in an artistic way. Consider, for instance how he builds a quasi-sentential theme(67) to start the second prelude (Example 29): the prelude starts with a tonic prolongation in C major, which forms a presentation; then, in mm. 9–11, Beethoven rapidly modulates from G major to D major, A major, and E major in one-measure units, which creates the effect of fragmentation that projects a medial continuation function. Beethoven thus manages to craft a sentential, theme-like unit despite the mechanically repeated modulation pattern that permeates the work.

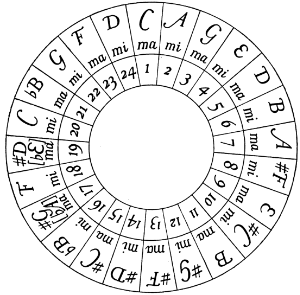

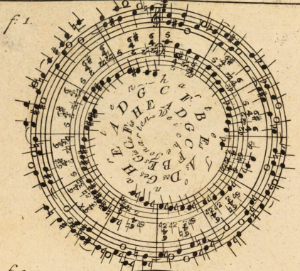

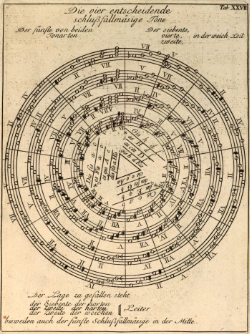

Example 31. Vogler’s Zirkelmäsige Fortschreitungen von einem willkührlichen Tone in alle andere Fünftenweis vorwärts; (Vogler 1776, XXVIII)

(click to enlarge)

[3.6] Nottebohm suggests that one of Vogler’s modulation circles found at the end of his zibaldone (Example 31) could have inspired Beethoven’s second prelude, but he was skeptical to attribute Beethoven’s prelude to any one treatise because the musical circle was commonly found in treatises in the late eighteenth century. He proposes some additional sources that may have inspired Beethoven’s preludes including Jacob Adlung’s Anleitung zu der musikalischen Gelahrtheit (1783) (likely in reference to Example 32) and Johann Samuel Petri’s Anleitung zur praktischen Musik (second edition, Leipzig, 1782, henceforth “Anleitung”; Nottebohm cites the pattern boxed in Example 33).(68) In what follows, I support Nottebohm’s first hypothesis, namely, that Vogler’s unusual modulation circle was the most likely inspiration for Beethoven’s second prelude.

Example 32. Jacob Adlung Cirkelgänge (top: ascending fourth; bottom: ascending fifth); (Adlung 1783, 387–90) (click to enlarge and see the rest) | Example 33. Petri Modulation Examples from C major to G major (Nottebohm highlights the boxed pattern); (Petri 1782, 257) (click to enlarge) |

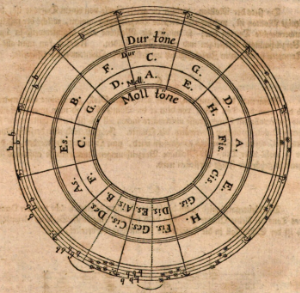

Example 34. Heinichen’s Musical Circle (Arnold 1931, 268)

(click to enlarge)

Example 35. Mattheson’s Circle (Arnold 1931, 277)

(click to enlarge)

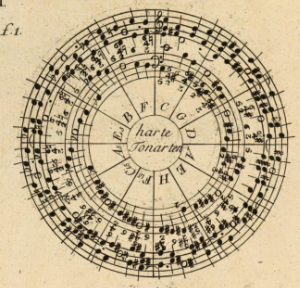

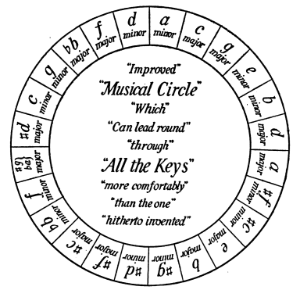

Vogler’s Unusual Musical Circle

[3.7] To understand why Beethoven’s preludes and Vogler’s circle are unusual, let me briefly outline the history of the musical circle.(69) The musical circle arose in eighteenth-century treatises in chapters that focus on improvisation. Heinichen seems to be the first to explicitly discuss the circle in his colossal thoroughbass treatise (1728) (Example 34). For him, the circle is useful for composition, realizing unfigured bass lines, preluding on keyboard, and abolishing the old church modes.(70) In essence, the circle helps one recognize which keys are closely related to the chosen home key so that one may create a coherent modulation plan. Heinichen does not suggest, however, that one should compose a piece that modulates through every key. After Heinichen, Mattheson included the device in his Grosse General-Bass-Schule (1731) with some modifications (Example 35)(71) in a chapter on improvisation. By the middle of the century, the circle was commonplace: C. P. E. Bach remarked, for example, about the “well-known Circle of Keys” in his chapter on improvisation in his Versuch über die wahre Art das Clavier zuspielen (1762)—a book that Neefe studied, which may have also been familiar to Beethoven in Bonn.(72)

[3.8] Given the popularity of the circle in the eighteenth century, Nottebohm’s hesitancy to link Beethoven’s op. 39 preludes to any one treatise seems warranted. But further inquiry diminishes this concern: most theorists presented the circle as a tool for modulation to closely related keys—it was not meant to be realized in its entirety. C. P. E. Bach emphasizes, for instance, that one should not have “obligation to the circle, for it would be wrong in this kind of piece [i.e., a fantasy] to make a cyclic excursion through all twenty-four keys.”(73) Moreover, the musical circles of Heinichen and Mattheson show the relation of major and minor keys a third apart, not a fifth, which is the interval Beethoven’s preludes proceed by.

Example 36. Petri Circle of Keys; (Petri 1782, 220)

(click to enlarge)

[3.9] As Nottebohm shows, we see stronger similarities between Beethoven’s preludes and the musical circle in Petri’s Anleitung (1782). Petri modifies the circle (Example 36) to have an inner (minor) and outer ring (major keys), which clarifies the circle-of-fifths patterns and separates the major keys from the minor. But Petri, like those before him, does not suggest that one should modulate through all twelve keys in a circular manner. Rather, he provides some examples of how one can modulate from C major to other keys (Example 33, discussed above, shows several patterns). Thus, although Nottebohm’s connection of Beethoven’s second prelude to Petri’s musical circle is apt, a better comparison remains.

Example 37. Transcription of Vogler’s Modulation by Fifths Upwards Circle

(click to enlarge)

[3.10] The musical circle that most convincingly matches Beethoven’s second prelude is the one found in Vogler’s zibaldone (Example 31, transcribed in Example 37). Vogler’s circle is atypical: whereas other eighteenth-century treatises present the musical circle in a more abstract way with key names or signatures, Vogler realizes the circle in a more extreme and literal fashion. Moreover, the modulation pattern is closely related to the pattern Beethoven uses in his second prelude. Vogler follows a consistent bass pattern that moves from ①, ⑦, to ⑥, whereupon ⑥ is reinterpreted as ② in the new key (i.e., a scale mutation occurs).(74) This pattern matches nearly all of Beethoven’s modulations in the second prelude, although Beethoven adds the new key’s ⑤ after the ⑥ becomes ② scale-mutation (refer to Example 29). It seems likely, therefore, that if Beethoven’s second op. 39 prelude was directly inspired by any example, it would have been Vogler’s circle.

[3.11] In addition to the strong similarities between Vogler’s modulating circle and Beethoven’s second prelude, some additional chromatic and modulation patterns in Vogler’s book, discussed more below, may have inspired elements of Beethoven’s first op. 39 prelude. As Kramer (2016, 16–20) observes, the bridge from

Example 38. Beethoven, op. 39, Prelude 2, mm. 20–21; enharmonic seam (click to enlarge) | Example 39. Beethoven, op. 39, Prelude 1, mm. 38–58 (click to enlarge) |

Example 40. Excerpt of Vogler’s modulation patterns, from C major to (click to enlarge) | Example 41. Excerpt of Vogler’s modulation patterns, from C minor to (click to enlarge) |

[3.12] Beyond the strong similarity between Vogler’s atypical, modulation circle and Beethoven’s second prelude and the more distant link between chromatic patterns and marked modulation schemes in Vogler’s book and Beethoven’s first prelude, we lack unequivocal evidence that proves that Beethoven encountered Vogler’s work. We know, however, that Vogler visited Bonn before Beethoven left for Vienna(75)—perhaps Vogler brought his freshly written book to promote it with other esteemed musicians in Bonn. Or, perhaps Vogler’s book made its way to Bonn by order of the Government of Palatinate (per Leopold Mozart). Alternatively, maybe Neefe ordered a copy; we know he had connections in Mannheim (recall that he had Beethoven’s first variations engraved there) when Vogler served as Vice-Kappelmeister there. Whatever the case, Vogler’s zibaldone would have been a great source for the young Beethoven to study because it combines theoretical concepts that Bonn’s musicians were accustomed to (e.g., the fundamental bass) with numerous practical examples for budding composers. Let us therefore accept Nottebohm’s hypothesis that Beethoven encountered this treatise in Bonn and explore what he would have studied.

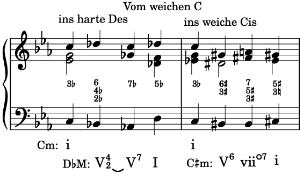

Summary of Vogler’s Kürpfälzische Tonschule

[3.13] As the contents of Vogler’s Kürpfälzische Tonschule have not been summarized in English to my knowledge, let me highlight and categorize some of its most salient elements in some detail.(76) The patterns we find in Vogler’s work are ubiquitous in Beethoven’s music, including in his early Bonn works, so this summary will not lead to direct comparisons with Beethoven’s early music outside his op. 39 preludes. Instead, this précis aims to provide a window into the rich musical thinking and practice that Beethoven would have likely encountered in Bonn.

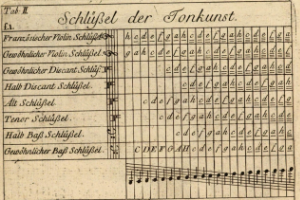

Music Rudiments

[3.14] The first five pages of Vogler’s book introduces basic music information such as clefs, rhythms, meters, and so forth, in addition to scales in every key (with fingering),(77) diminution patterns, embellishing tones, and keyboard figures such as trills, movement in thirds, and more (consider Example 42 and Example 43). Later in the book, Vogler provides other useful information for the practicing musician such as patterns for tuning a piano (Example 44) and harmonic patterns for testing the tuning (Example 45).

Example 42. Vogler Gründe p. 1, Tab. II Partial Transcription and Analysis (click to enlarge and see the rest) | Example 43. Vogler Gründe p. 1, Tab. III (click to enlarge and see the rest) |

Example 44. Tab XVI, Fig. 5; Practical [Patterns] for Piano Tuning (click to enlarge) | Example 45. Tab XVI, Fig. 6–11; “Testing the Tone for Piano Tuning through Harmonies” (click to enlarge) |

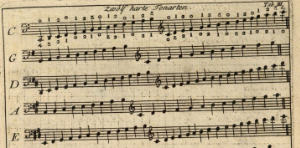

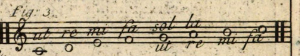

Solfeggio and Singing Exercises

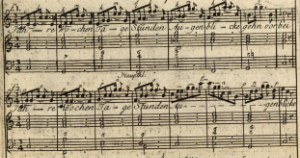

Example 46. Vogler’s Gründe, Tab VII, Fig. 3

(click to enlarge)

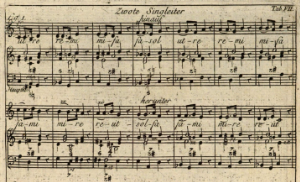

[3.15] After the rudimentary musical information, Vogler introduces a series of singing exercises that employ hexachordal solfeggio with the hard and natural hexachords (see Tab VII, Figure 3; Example 46).(78) Consider several examples. In the first exercise (Example 47) a student sings an ascending and descending stepwise octave with a sequential, chromatic keyboard accompaniment (note the mutation on sol in mm. 4–5). In the next exercise (Example 48), they practice adding an incomplete lower neighbor to the first note followed by a leap of a third. Thereafter (Example 49 and Example 50), they learn to embellish each scale step with more extensive neighboring motion. (In these two examples, the topmost staff of both examples provide the underlying structure of the neighboring motion—note that the embellishing neighboring notes do not receive solmization syllables—and the staff below introduces a more elaborate embellishment with a syncopated rhythm.)(79)

Example 47. Vogler’s Gründe p. 5, Tab VI, (click to enlarge) | Example 48. Vogler’s Gründe p. 6, Tab VII, (click to enlarge) |

Example 49. Vogler’s Gründe, Tab VIII, Fig. 1 (click to enlarge) | Example 50. Vogler’s Gründe, Tab IX, Fig. 1 excerpt (click to enlarge) |

[3.16] After these basic exercises, Vogler introduces more complex exemplars (“Übungen für die Stimm”). The first example teaches the student triadic arpeggiation (Example 51, Figures 1 and 2). Each exercise, though mechanical, builds a prototypical eight measure theme: observe how Figures 1 and 2 (analyzed in Example 52)(80) begin with four-measure tonic prolongations followed by cadential progressions. In addition, Vogler couples the exercises with the fundamental bass (labeled “Hauptkl[ang]”, written below the basso continuo). The student thus learns to associate several interrelated ideas including solfeggio, embellishment, thoroughbass, the fundamental bass, and basic theme structures while combining playing and singing.

Example 51. Vogler’s Gründe, Tab X, (click to enlarge) | Example 52. Analysis of Vogler’s Gründe, (click to enlarge and see the rest) |

Example 53. Vogler’s Gründe Tab IX, Fig. 2–6

(click to enlarge)

Example 54. Vogler’s Gründe, Tab XI, Fig. 3

(click to enlarge)

[3.17] Vogler adds several additional singing examples that demonstrate how to embellish a structural harmony or melody with different types of vocal diminution patterns. For instance, Tab IX, Figures 2–6 (Example 53) show how to arpeggiate changing harmonies. In a later example (Tab XI, Figure 3; Example 54) a student learns how to embellish a melody four different ways over a bassline. Vogler provides the structural melody in quarter-notes that articulates a sequential pattern (up a third, down a second). Below, in the second and third staves from the top, he adds a syncopated elaboration of the structural melody. In the fourth and fifth staves he embellishes further the melody with eighth note ascending and descending diminution patterns. Beethoven would have presumably progressed from singing the top melody to those below it, all while playing the basic figured bass accompaniment. He may have also recognized the miniature theme: the bass begins with a tonic prolongation built with alternate tonic and dominant harmonies (mm. 1–3), then a cadential progression follows (④6, ⑤, ① in m. 4).

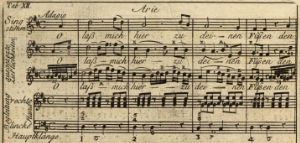

[3.18] After these singing exercises, a student would progress to singing and playing complete arias with and without embellishment. Example 55 provides an excerpt of Vogler’s aria, “O laß mich hier zu deinen Füßen” (“O leave me here at your feet”).(81) As before, the bottom two staves of the aria provide the accompaniment (labeled Begleitung) and the top staves provide a texted melody, with two additional staves below that embellish the melody with increasingly complex figuration (ausgesezte Zierlichkeiten). The keyboard accompaniment was likely taught before the complete aria because Vogler provides several examples that match the accompaniment on the previous page in the treatise (compare the patterns in Example 56 with the accompaniment in Example 55).

Example 55. Vogler’s Gründe, Tab XII, Fig. 1 (click to enlarge) | Example 56. Vogler Gründe, Tab XI, Fig. 4–21 (click to enlarge) |

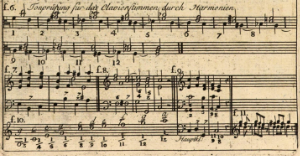

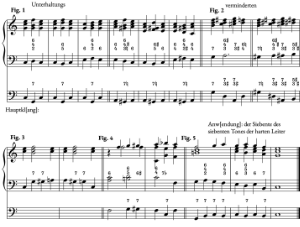

Thoroughbass, Harmony, and Keyboard Patterns

[3.19] Alongside the gradually more elaborate singing exercises, Vogler intersperses numerous practical keyboard patterns that are characteristic of the Rameau-influenced, northern-Italian thoroughbass tradition. Although these patterns are written predominantly in C major, it is assumed that a student would transpose them to every key. Let us examine these patterns in some detail.

Example 57. Vogler’s Gründe, Tab: VII

(click to enlarge and see the rest)

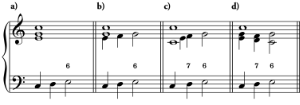

Example 58. Vogler’s Rule of the Octave; (Vogler 1778, VII Fig. 9)

(click to enlarge)

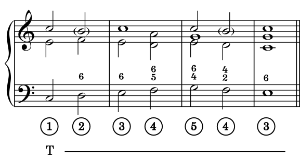

[3.20] In Tab VII (on the same page that introduces the embellished solfeggio exercise; see Example 49, shown in full in Example 57), Vogler provides the RO (Vogler’s Figure 9, transcribed in Example 58).(82) Vogler’s RO is presented somewhat differently than those found in partimenti sources because he also includes the fundamental bass (labeled Hauptkl[ang]) in small notes underneath the ascending basso continuo voice, which differs in some places from Rameau’s fundamental bass.(83) The differences between Vogler’s fundamental bass and Rameau’s suggests a different focus: the fundamental bass in Vogler’s book serves a pedagogical and analytical role rather than a generative principle for harmonic progression as it appears in Rameau’s treatise and Kirnberger’s Grundsäzte discussed above.(84) Despite this difference, Vogler’s figures match influential RO’s by written by authors such as Rameau and David Kellner.(85)

[3.21] Immediately below the RO (in Figure 10: see the bottom of Example 57, transcribed in Example 59) Vogler includes the “other manner” of playing the ascending and descending scale with 5–6 and 7–6 figures. The ascending and descending patterns are presented one after the other, just as other Napolean partimento masters introduce them (e.g., Giacomo Insanguine and Giovanni Paisiello).(86) As Sanguinetti (2012, 136–37) explains, the ascending 5-6 and descending 7-6 scale harmonizations are immensely practical because they afford numerous variants, including ascending chromatic variants.(87) Beethoven uses a modified, ascending-chromatic variant of the 5-6 pattern in his op. 39, first prelude; see Example 60. Like the RO, Vogler’s presentation of the “other manner” differs from partimento sources because he also supplies the analytical fundamental bass in smaller bass notes below the basso-continuo voice. In this way, he visually couples fundamental bass theory with thoroughbass practice.

Example 59. Vogler’s Gründe, Tab VII, Fig.. 10; Vogler’s ascending 5-6 and descending 7-6 progressions (click to enlarge) | Example 60. Beethoven, op. 39, Prelude 1, (click to enlarge) |

Example 61. Vogler’s Gründe, Tab XVII,

(click to enlarge)

Example 62. Vogler’s Gründe, Tab XVII,

(click to enlarge)

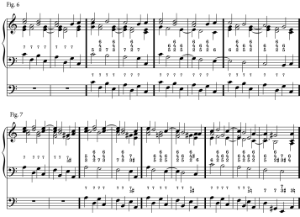

[3.22] In addition to the RO and “alternate” manner of harmonizing an ascending and descending octave, Vogler adds exercises for resolving dominant seventh and diminished seventh harmonies in major and minor keys. In Tab XVII, Figure 1 (Example 61 transcribed in Example 62), a student practices six resolutions of tonic–dominant (or fully diminished seventh in minor)–tonic with inversions.(88) Figure 2 introduces a rising second in the basso continuo, with a chromatic line in the right hand—presumably a student would practice this pattern by continuing the chromatic sequence upwards. Observe, too, how the first basso continuo moves a whole step from G to A, but as the fundamental bass shows, Vogler interprets this pattern to involve four harmony changes. These four harmonies are reflected in the second iteration thereafter with the chromatic ascent from

[3.23] In the next examples, a student learns the relationship between the dominant seventh and fully diminished seventh. For instance, in Figure 3 (Example 62), the pattern moves from a major key to its relative minor and back by changing the bass chromatically from ⑤ to ↑⑤ with a diminished harmony held in the right hand. In Figure 4, Vogler provides a cadential progression with a chromatic basso continuo that steps ③, ↑④, ⑤, before leaping to ① with chromatic movement in the top-most voice. And finally, in Figure 5, a student learns to play conjunct motion in the basso continuo harmonized with dominant sevenths, fully diminished sevenths, and tonic harmonies. As is typical, Vogler adds the fundamental bass as an analytical layer below each progression.

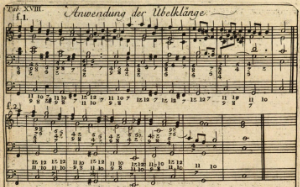

Example 63. Vogler’s Gründe, Tab XVIII,

(click to enlarge)

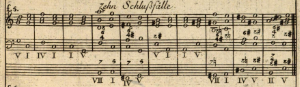

[3.24] Additional keyboard patterns in Vogler’s treatise include sequential exercises to practice the resolution of suspension chains (Example 63; “Anwendung der Übelklänge”) and ten cadence patterns with analytical roman numerals (Example 64).(89) Several of the “cadences” are unique to Vogler. See Example 65. In a major key, using the same logic of the diminished seventh’s leading tone ⑦ resolving to its tonic ① (Example 65A), Vogler proposes a (half) cadence with ↑④, acting like a leading tone, resolving to ⑤ (V) in (Example 65B). (According to Vogler, the half-diminished four-three harmony arises from an inverted harmony that has ↑④ as its root.) He follows the same idea in minor with the leading tone harmony resolving to the tonic (Example 65C), which he extends to ↑④ resolving to ⑤ as dominant (D and E) in a minor key. Thus, Vogler’s (

Example 64. Vogler’s Gründe, Tab XXI, Fig. 5, Ten Cadences (click to enlarge) | Example 65. Vogler’s Leading-tone Cadence Patterns (click to enlarge) |

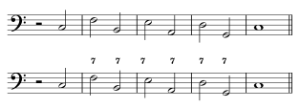

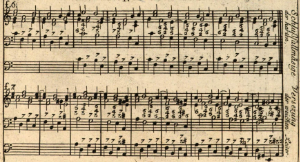

[3.25] In addition to the patterns so far mentioned, Vogler includes invertible, diatonic, seventh-chord sequences with descending suspension-chains in major and minor keys (see Example 66, transcribed in Example 67). Presumably, a student would learn the root position version (down a fifth, up a fourth diatonically), then three inversions (dark black bars segment each inversion pattern) and transpose these patterns to every key. As is standard in Vogler’s book, each of the sequence patterns include an analytical fundamental bass on a third staff below, which is not to be played, that demonstrates clearly that all four versions have the same underlying root motion. These invertible patterns afford composers with a rich tapestry of useful contrapuntal possibilities for building imitative, invertible counterpoint structures and for fugal improvisation and composition.(91)

Example 66. Vogler’s Gründe, Tab XXI, Fig. 6 and 7 (sequences with descending fifths) (click to enlarge) | Example 67. Vogler’s Gründe, Tab XXI, Fig. 6 & 7 Transcribed (darker bars added) (click to enlarge) |

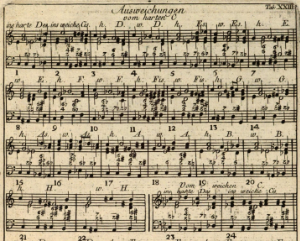

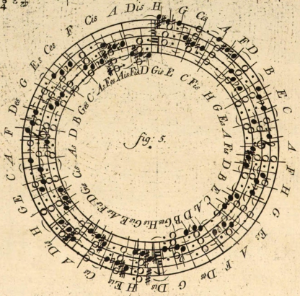

Example 68. Vogler’s Gründe, Tab XXIII,

(click to enlarge)

[3.26] Beyond the invertible, suspension-chain sequences, Vogler includes a notable set of extensive modulation patterns (e.g., Example 68). Using only four harmonies, Vogler’s patterns modulate from the major and minor keys of C, E, and

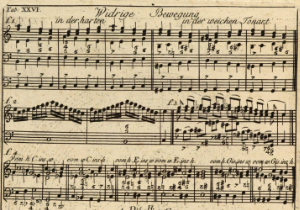

Example 69. Vogler’s Gründe, Tab XXVI,

(click to enlarge)

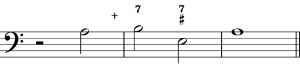

[3.27] Finally, Vogler presents some “contrary motion” (widrige Bewegung) examples at the end of the zibaldone. These patterns foreground: contrary motion in major and minor keys (Example 69, Figure 1); a sixteenth-note run over a bass that moves from ①-⑦-① (Figure 2); a chromatic, contrary motion pattern that starts with the tonic and ends with a PAC (Figure 3); and modulation patterns that move from C, E, and

[3.28] In general, the keyboard patterns Vogler provides are not exhaustive. Rather, they are intended to inspire a musician to invent freely as realized Gebrauchs-formulas (exemplars).(95) Vogler explains in his Betrachtungen der Mannheimer Tonschule (p. 4), for instance, that “hundreds of sorts of passages, sequences, harmonies, simultaneities, inversions, etc. can etch into the mind a rich inventive faculty for the organist, the amateur accompanist, or the composer; they can make him agile in all situations with living practice, and without noticing it his mind will be filled with harmonic turns.”(96) In other words, Vogler’s patterns are a gateway into free improvisation and composition.(97)

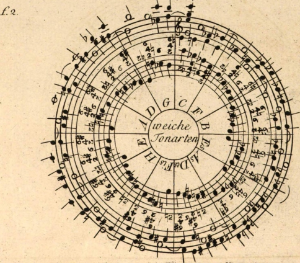

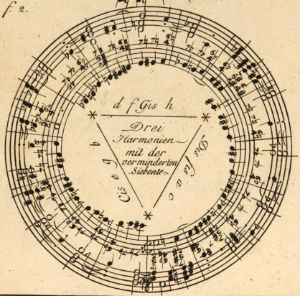

Vogler’s Circles

[3.29] To conclude our study of Vogler’s work, let us examine the unusual circles that Vogler provides at the end of his book. The music circle that may have inspired Beethoven’s op. 39 second prelude is one of eight other circles in Vogler’s zibaldone. In addition to modulation by ascending fifth for major keys (discussed above; see Example 30 and Example 31), Vogler provides an example for modulation by ascending fifth in minor keys (Example 70) and circles for modulation by descending fifth in the major (Example 71) and minor keys (Example 72). In each of these circles, the bass moves by descending conjunct motion (when the bass voice moves too low, Vogler resets the register with a leap).

Example 70. Vogler’s Gründe, Tab XXVIII, (click to enlarge) | Example 71. Vogler’s Gründe, Tab XXIX, (click to enlarge) |

Example 72. Vogler’s Gründe, Tab XXIX, (click to enlarge) | Example 73. Vogler’s Gründe, Tab XXX, Fig. 1; From an arbitrary to key all other major and minor keys (click to enlarge) |

Example 75. Scale Step Analysis of Tab XXX, Fig. 1 excerpt

(click to enlarge)

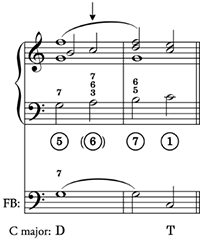

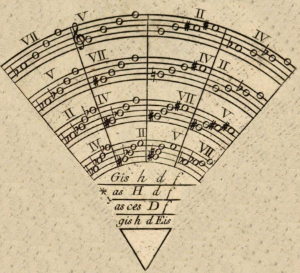

[3.30] Beyond the separate major and minor modulation circles, Vogler provides a circle that embeds modulation to all the major and minor keys together (Example 73). The pattern (see Example 74) involves a descending, conjunct bass voice that takes alternating

Example 74. Transcription of Tab XXX, Fig. 1 (click to enlarge) | Example 76. Interlocking Ascending P4 or Descending P5 Patterns (click to enlarge) |

Example 77. Vogler’s Gründe, Tab XXX, Fig. 2; chromatic conjunct movement filling a minor third structured with the three diminished seventh harmonies

(click to enlarge)

[3.31] Vogler’s circles do not stop at modulation with dominant seventh chords. He supplies another circle (Example 77), the so-called circle of omnibus progressions,(98) with an ascending chromatic bassline that expresses three chords per measure, figured 7, 7,

Example 79. Vogler’s Gründe, Tab XXVI, Fig. 5

(click to enlarge)

[3.32] In each of the three sectors of the circle in Example 77 (partitioned with the triangle in the middle of the circle; see Example 78), the bass steps chromatically up an octave so that the first pitch is expressed as its enharmonic equivalent (e.g.,

Example 78. Tab XXX, Fig 2., Sector d f Gis h (transcription) (click to enlarge) | Example 80. Partial transcription and Analysis of Vogler’s Gründe, Tab XXVI, Fig. 5 (click to enlarge) |

Example 81. Beethoven, op. 39, no. 1, mm. 1–6

(click to enlarge)

[3.33] Perhaps Vogler’s chromatic, stepwise patterns inspired the chromatic ascending and descending lines in Beethoven’s first prelude (op. 39). Compare the patterns in Example 74, Example 78, and Example 79 or Example 80 with the prelude’s opening excerpt shown in Example 81 (ascending chromatic lines are colored blue and descending red). Like Vogler’s patterns, the harmonies in Beethoven’s first prelude change when notes move chromatically.

Example 82. Vogler’s Gründe, Tab XXVII

(click to enlarge)

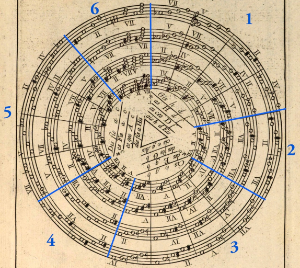

[3.34] Finally, consider Vogler’s largest and most elaborate circle, Die vier entscheidende schlußfallmäsige Töne (roughly, “the four different cadences,” Example 82). This circle, unlike the others previously discussed, does not introduce a modulation pattern. Instead, it catalogs four dominant functioning chords that lead to “cadences” (in Vogler’s sense of the term, see Example 64 and Example 65), which arise from successive perturbations of a diminished seventh chord.(100) By altering consecutively one pitch of each harmony by a semitone, Vogler builds the dominant seventh (represented with “V”), the fully diminished seventh (“VII”), the German augmented sixth (“IV”) and the French augmented sixth (“II”) harmonies.(101) To better understand the purpose of this circle, let us examine it in greater detail.

[3.35] Vogler’s circle partitions into six sectors (Example 83). Three sectors (1, 3, 5) are associated with text written at the center of the circle above the triangle edges (reminiscent of Example 77). Consider sector 1 (Example 84).(102) Above the triangle at the middle of the circle, Vogler writes four different ways of spelling a fully diminished seventh chord (e.g., Gis, h, d, f or

Example 83. Vogler’s Gründe, Tab XXVI partitioned into 6 sectors (click to enlarge) | Example 84. Sector 1 (extracted from Tab XXVI) (click to enlarge) |

Example 85. Sector 1, Outermost Ring Transcription

(click to enlarge)

Example 86. Sector 1, Outermost Ring, Harmonic Analysis

(click to enlarge)

Example 87. Sector 1 Transcription and Resolution Targets

(click to enlarge)

[3.36] Consider now the outermost ring of sector 1 (transcribed in Example 85) and observe how each chord is related to the next by a difference of one semitone: to change VII to V, Vogler lowers the

Conclusion

[4.1] To summarize, Kirnberger’s Grundsätze and Vogler’s zibaldone are densely packed, pragmatic treatises that appear to espouse the sophisticated kinds of musical thinking, theorizing, and imagination that was circulating in Bonn during Beethoven’s adolescence. It is likely that Beethoven studied Kirnberger’s Grundsätze because he copied examples and text from it, it corresponds well with Neefe’s proclaimed pedagogy, and some of its patterns match structures found in Beethoven’s earliest “Elector” sonatas. The evidence that links Beethoven to Vogler’s zibaldone is less direct: Beethoven may have based his unusual, second op. 39 prelude off a similar modulating circle at the end of Vogler’s treatise; several chromatic and modulation patterns parallel many features found in the first prelude; and it is likely that Vogler’s work was known in Bonn, either by order of the Palatinate Government, from a direct visit from Vogler, or through the close connection between prominent musicians in Bonn and Mannheim.

[4.2] The two treatises surveyed in this study complement each other well. Kirnberger’s Grundsätze could have introduced Beethoven to important theoretical concepts such as the fundamental bass, harmonic function and progression, and the principles of harmonic prolongation and analysis. Vogler’s zibaldone could have provided practical training in solfeggio, provided rich thoroughbass patterns with diminution suggestions, extensive modulation schemas, and more. These two treatises were examined and analyzed not only because of the evidence that links them to Beethoven, but also because they espouse ideas that correspond well with what we know about his music and teachers. Ultimately, however, these treatises do not offer a comprehensive view of the musical education Beethoven received in Bonn—they merely provide windows into it.

[4.3] When we examine more closely the treatises that Nottebohm connects to Beethoven’s Bonn years, we may find some that were unlikely to have been relevant for Beethoven’s music education. Kirnberger’s Gründsatze and Vogler’s zibaldone are not of this type: they are concise, practical, and sophisticated treatises that would have been appropriate for a young budding musician that distinguished musicians in Bonn thought could become the next Mozart. Beyond these two treatises, we have evidence that Beethoven worked with other important sources in Bonn including Johann Mattheson’s Der vollkommene Capellmeister (1739) and Kirnberger’s larger Die Kunst des reinen Satzes in der Musik, Volume 2 (1776). Beethoven appears to have studied these treatises to improve his invertible counterpoint (see Kramer 1975, 86–99), and perhaps he consulted Kirnberger’s Kunst alongside the Gründsatze to study materials the latter treatise lacked such as choral harmonization, another pillar of standard eighteenth-century composition pedagogy.(104)

[4.4] Our knowledge of Beethoven’s lessons in Bonn may always be more conjectural than our knowledge of his studies in Vienna, but this limitation should not discourage us from pursuing this research. As John Wilson (2020, 1–2) laments:

The tendency to undervalue Beethoven’s Bonn years has, until very recently, been entrenched in both popular and scholarly narratives of the composer’s creative development. . . . Bonn Beethoven is too often viewed retroactively as a harbinger of Vienna Beethoven, particularly Heroic Beethoven, with the composer denied serious consideration as a rational individual operating in a particular set of circumstances.

As scholars begin to reappraise the rich historical musical life in Bonn more generally,(105) the time is ripe to explore further Beethoven’s Bonn years, both through the analysis of his early works and detailed source study. We will likely conclude that Beethoven’s abilities were instilled with careful study of the best treatises and music available to him under the leadership of expert pedagogues.

[4.5] It is apparent that Beethoven encountered many treatises in Bonn, and as the epigraph suggests, he studied them diligently.(106) He must have also advanced considerably by performing and studying numerous composers’ music: by the time Beethoven was a teenager, Bonn had one of the largest collections of musical works in Germany.(107) Beethoven must have also benefited from regular interaction with high-caliber musicians connected to the city and his family. We should not forget, for example, that his grandfather once held the title of Bonn Kapellmeister. The Beethoven family, like the Mozart or Bach family, has a rich musical heritage.

[4.6] Future studies may uncover additional relationships between Beethoven’s early music and contemporary musical treatises, works by other composers, and pedagogical traditions. Nottebohm’s studies of this period are due for translation, source verification, and further research.(108) We might also learn from critically studying the materials that Beethoven compiled for teaching Archduke Rudolph,(109) and from surveying the treatises that Beethoven had in his personal library at his passing; see the table in Example 88.(110) The two treatises discussed in this article are only part of a much larger story; Example 89 provides a cursory sketch of some of the people and music-theoretic sources that likely influenced Beethoven.(111) Our fascination with Beethoven’s music must owe, in part, to the sources and people that helped shape it.

Example 88. Beethoven’s Inventoried Library of Musical Treatises (click to enlarge) | Example 89. Sketch of Beethoven’s Nexus of Influence (click to open in new tab) |

Thomas William Posen

The College of Idaho

2112 Cleveland Blvd

Caldwell, ID 83605

tposen@gmail.com

Works Cited

Adlung, Jacob. 1783. Anleitung Zu Der Musikalischen Gelahrtheit. Edited by Johann Adam Hiller. 2nd ed. Breitkopf.

Agmon, Eytan. 2023. “‘Aus Mozart gestohlen’: Beethoven und Die Entführung aus dem Serail.” Music Theory Online 29 no. 2. https://www.mtosmt.org/issues/mto.23.29.2/mto.23.29.2.agmon.html.

Albrechtsberger, Johann Georg. 1790. Gründliche Anweisung Zur Composition. Johann Gottlob Immanuel Breitkopf.

Anderson, Emily. 1961. The Letters of Beethoven. MacMillan; St Martin’s Press.

—————, ed. 1989. The Letters of Mozart and His Family. 3rd ed. W. W. Norton.

Arnold, Franck Thomas. 1931. The Art of Accompaniment From a Thorough-Bass as Practised in the XVIIth & XVIIIth Centuries. Oxford University Press, H. Milford.

Austin, Cecil. 1939. “Beethoven and the Organ.” The Musical Times 80 (1157): 525–27. https://doi.org/10.2307/923411.

Bach, Carl Philipp Emanuel. 1948. Essay on the True Art of Playing Keyboard Instruments. Translated by William J. Mitchell. Annotated edition. W. W. Norton.

Bach, C. P. E. 1762. Versuch über die wahre Art das Clavier zu spielen. Printed by Christian Friedrich Henning [1753, Part One] and George Ludewig Winter [1762, Part 2].

Baragwanath, Nicholas. 2020. The Solfeggio Tradition: A Forgotten Art of Melody in the Long Eighteenth Century. 1st ed. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780197514085.001.0001.

Beethoven, Ludwig van. 1832. Studien im Generalbass, Contrapunkt und in der Compositionslehre. Edited by Ignaz Seyfried. Tobias Haslinger.

—————. 1853. Louis van Beethoven’s Studies. Edited by Ignaz Seyfried. Translated by Henry Hugo Pierson. 2nd ed. Schuberth and Comp.

Biamonti, Giovanni. 1968. Catalogo Cronologico e Tematico Delle Opere Di Beethoven: Comprese Quelle Inedite e Gli Abbozzi Non Utilizzati. Industria Libraria Tipografica Editrice.

Byros, Vasili. 2009. “Foundations of Tonality as Situated Cognition: An Enquiry into the Culture and Cognition of Tonality, with Beethoven’s Eroica Symphony as Case Study.” PhD diss., Yale University.

Caplin, William E. 2008. “Schoenberg’s ‘Second Melody,’ or, ‘Meyer-Ed’ in the Bass.” In Communication in Eighteenth-Century Music, ed. Danuta Mirka and Kofi Agawu, 160–86. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511481376.007.

—————. 2013. Analyzing Classical Form: An Approach for the Classroom. Oxford University Press.

Christensen, Thomas. 2010. “Thoroughbass as Music Theory.” In Partimento and Continuo Playing in Theory and in Practice, ed. Dirk Moelants. Leuven University Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt9qdxdv.

Cone, Edward T. 1968. Musical Form and Musical Performance. W. W. Norton.

Cooper, Susan. 2022. “‘The Bonn Master-Baker Gottfried Fischer’s Reminiscences of Beethoven’s Youth’ [Des Bonner Bäckermeisters Gottfried Fischer Aufzeichnungen Über Beethovens Jugend].” Translated into English, with Editorial Commentary and Notes. The Beethoven Journal 35 (3). https://doi.org/10.55917/2771-3938.1003.

Corneilson, Paul. 1998. “Vogler’s Method of Singing.” The Journal of Musicology 16 (1): 91–109. https://doi.org/10.2307/764078.

Damschroder, David. 2008. Thinking about Harmony: Historical Perspectives on Analysis. 1st ed. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511482069.

David, Hans T., Arthur Mendel, and Christoph Wolff. 1998. The New Bach Reader: A Life of Johann Sebastian Bach in Letters and Documents. W. W. Norton.

DeNora, Tia. 2023. Beethoven and the Construction of Genius: Musical Politics in Vienna, 1792–1803. University of California Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/jj.2711635.

Diergarten, Felix. 2011. “‘The True Fundamentals of Composition’: Haydn’s Partimento Counterpoint.” Eighteenth-Century Music 8 (1): 53–75. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1478570610000412.

—————. 2017. “Editorial.” Eighteenth Century Music 14 (1): 5–11. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1478570616000270.

Diergarten, Felix, and Ludwig Holtmeier. 2011. “Nicht Zu Disputieren: Beethoven, Der Generalbass Und Die Sonate op. 109.” Musiktheorie 26 (2): 123–46.

Emmerig, Thomas. 1985. “Joseph Riepel (1709-1782) und seine musiktheoretischen Schriften.” Die Musikforschung 38, no. 1: 16–21. https://doi.org/10.52412/mf.1985.H1.1462.

Everett, Walter. 2020. “Becoming Beethoven: Theorizing Bonner Zeit Transitions.” Music Theory and Analysis (MTA) 7 (1): 113–80. https://doi.org/10.11116/MTA.7.1.3.

Fischer, Gottfried, and Joseph Schmidt-Görg. 1971. Des Bonner Bäckermeisters Gottfried Fischer Aufzeichnungen Über Beethovens Jugend. Veröffentlichungen Des Beethovenhauses in Bonn, n.F. Reihe 4: Schriften Zur Beethovenforschung 6. Beethovenhaus; G. Henle.

Frimmel, Theodor von. 1906. Bausteine Zu Einer Lebensgeschichte Des Meisters. Beethoven Studien 2. Georg Müller.

Gjerdingen, Robert O. 2007. Music in the Galant Style. 1st ed. Oxford University Press.

—————. 2011. “Gebrauchs-Formulas.” Music Theory Spectrum 33 (2): 191–99. https://doi.org/10.1525/mts.2011.33.2.191.

—————. 2020. Child Composers in the Old Conservatories: How Orphans Became Elite Musicians. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780190653590.001.0001.

Gooley, Dana. 2018. “Fantasies of Improvisation: Free Playing in Nineteenth-Century Music.” In The School of Abbé Vogler: Weber and Meyerbeer. Vol. 1. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780190633585.003.0002.

Gosman, Alan. 2009. “From Melodic Patterns to Themes: The Sketches for the Original Version of Beethoven’s ‘Waldstein’ Sonata, op. 53.” In Genetic Criticism and the Creative Process: Essays from Music, Literature, and Theater, ed. William Kinderman and Joseph E. Jones. University of Rochester Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781580467537.009.

Grant, Cecil Powell. 1977. “The Real Relationship between Kirnberger’s and Rameau’s ‘Concept of the Fundamental Bass.’” Journal of Music Theory 21 (2): 324. https://doi.org/10.2307/843493.

Grave, Floyd K. 1988. In Praise of Harmony: The Teachings of Abbe Georg Joseph Vogler. University of Nebraska Press.

Hass, Ole. 2012. “Wöchentliche Nachrichten Und Anmerkungen Die Musik Betreffend.” Retrospective Index to Music Periodicals (1760–1966) (blog). https://www.ripm.org/?page=JournalInfo&ABB=WNA.

Heinichen, Johann David. 1728. Der General-Bass in Der Composition. Dresden.

Jacobi, Erwin R. 1964. “Rameau and Padre Martini: New Letters and Documents.” Translated by Piero Weiss. The Musical Quarterly L (4): 452–75. https://doi.org/10.1093/mq/L.4.452.

Johnson, Douglas. 1982. “1794–1795: Decisive Years in Beethoven’s Early Development.” In Beethoven Studies 3, ed. Alan Tyson, 1–28. Cambridge University Press.