Reimagining Formal Functions in Post-Tonal Music: Temporality in the Semanticized Form of Salvatore Sciarrino*

Christian Utz

KEYWORDS: Salvatore Sciarrino; post-tonal music; musical form; formal functions; temporality; density; musical semantics

ABSTRACT: Modernist concepts of temporality (“non-linear time”) are variously cross-related to conventional concepts and qualities of time (“linear time”) (Kramer 1988, 20–65). This is exemplified by Salvatore Sciarrino’s creative method, which reconciles more conventional elements of discursive organicist design (processes of accumulation, multiplication, and transformation) with strategies of rupture and formal deterioration (“little bang,” “window form”). This unique mixing of “linear” and “non-linear” strategies is staged within a soundscape of mostly minimal dynamics and reduced activity at the edge of silence, sensitizing the listener toward micro-alterations. This article introduces key strategies in Sciarrino’s temporal form based on analytical investigations of three works that differ substantially in duration, density, and genre: Quintettino no. 1 (1976, ca. 3 min.) for clarinet and string quartet, Efebo con radio (1981, ca. 11 min.) for voice and orchestra, and the music theater work Da gelo a gelo: 100 scene con 65 poesie (2006, ca. 110 min.). My analyses are framed by a discussion of the relationships between musical beginnings or endings and constellations of duration and density. Sciarrino’s works prominently feature a semanticization of musical material by metaphorical, agential, or paratextual means that is also evident in his interpretation of Anton Webern’s orchestral piece op. 6, no. 4 (1909). The analyses demonstrate how the composer’s explicit and implicit semanticization of his material allows the listener to understand Sciarrino’s works as reimaginations of conventional formal functions in which the familiar appears unfamiliar.

DOI: 10.30535/mto.29.4.7

Copyright © 2023 Society for Music Theory

1. Introduction: Temporal Form in Post-Tonal Contexts

[1.1] According to Theodor W. Adorno, works of art in modernity critique societal oppression by failing to end affirmatively, thereby exhibiting the impossibility of unifying synthesis: “That this is denied artworks, that they can no more die than can the hunter Gracchus [referring to Franz Kafka’s 1917 short story fragment], is internalized by them directly as an expression of horror. The unity of artworks cannot be what it must be: the unity of the multiplicitous; in that unity synthesizes, it damages what is synthesized and thus the synthesis” (2002, 147).(1) Although in earlier music history, one might find traces of non-affirmative beginnings or endings—e.g., in self-reflexive suspended or evaded closures of Haydn’s mid-period works (Irving 1985; Neubacher 1986; Webster 1991, 152–55)—open, denied, or unprepared endings (as well as similarly undefined or unconventional beginnings) become the rule, rather than the exception, in large areas of twentieth-century music. A decisive feature of modernity in the temporal arts—in music in particular—might therefore be seen in the challenge toward, suspension of, or even abolition of conventional temporal functions, transcending a type of temporal continuity that can be expressed by the “beginning–middle–end paradigm” (Agawu 1991; Caplin 2009; Arndt 2018). Adorno’s Philosophy of New Music raises critical arguments against certain manifestations of this trend. Noting first how Schoenberg’ late dodecaphonic style “no longer countenances conclusions,” Adorno argues: “Ever since the dissolution of tonality, formulaic harmonic cadences no longer exist. Now they are also eliminated rhythmically. Ever more frequently, the end of the composition falls on the weak beat of the measure and has the quality of being an interruption” (2006, 179–80).(2) Many postwar composers have turned this putative shortcoming into a valued quality, most notably György Ligeti who, in his groundbreaking essay “Metamorphoses of Musical Form” ([1960] 1965) and his contemporaneous sound compositions, aimed to re-invoke the quality of temporal flow, without simply re-installing familiar formal conventions. Ligeti’s Apparitions (1958–59), according to Gianmario Borio, thus succeeds in creating “a kind of ‘pseudo-causality’

[1.2] Such attempts at reinventing temporal experience for musical listening were part of an unprecedented genre- and experience-related self-reflexivity, which has emerged since the 1950s as a distinctly modernist implication of “composing time.” This approach has made the experience of time a consciously modified feature of musical form. The Italian composer Salvatore Sciarrino (born 1947) is a key figure in this long process as his works (and writings) show a particular breadth and sensitivity in re-configuring parameters of temporal experience in a compositional process that is intimately linked to a thorough exploration of music perception, that is, a “composition of hearing” (Carratelli 2006).(4) He follows Ligeti in acknowledging (and appreciating) the essentially spatial processes of musical composition and listening, creating malleable formal environments in which sound events can be experienced as interconnected or isolated in an imagined space-time.

[1.3] Modernist concepts of suspended or modified temporality, in which conventional expectations or implications cannot be applied during listening (“non-linear time”), arguably are variously cross-related to conventional concepts and experiential qualities of time (“linear time,” Kramer 1988, 20–65)—with such concepts being permanently re-adjusted in the history of musical listening (Aringer et al. 2017; Thorau and Ziemer 2019). The dissociation of linear time in postwar serial music (which equally became subject to Adorno’s critique) has given way to profoundly different attempts in postserialist compositions—such as Karlheinz Stockhausen’s Gruppen (1955–57), Ligeti’s Apparitions or Giacinto Scelsi’s Fourth String Quartet (1964)—at regaining and enhancing temporal dimensions for the listening experience (Utz 2020, 344–45). Certainly these works do not reinstall conventional linear time; rather, they more likely conform to what Kramer describes as “nondirected linearity,”

a kind of linearity different from that of tonal music. Music exhibiting this special time sense. . . is, like tonal music, in constant motion, but the goals of this motion are not unequivocal. Nondirected linearity would have been unthinkable, even self-contradictory, in earlier Western music. But it is quite appropriate in this century, given the breakdown of goal orientation in much recent music. Nondirected linear music avoids the implication that certain pitches can become totally stable. Such music carries us along its continuum, but we do not really know where we are going in each phrase or section until we get there. (Kramer 1988, 39–40)

[1.4] From music-theoretical and -psychological perspectives, it seems obvious that functions of ending and closure, and consequently unambiguous temporal contiguity, are generally less pronounced in post-tonal music (Boyle 2018). Moreover, the impact of performance art, electroacoustic media, and soundscape since at least the 1940s has opened the closed space of the musical work to “ecological” experiences of hearing in a broad sense. This trend has also left its mark on Sciarrino’s music: intentionally blurring the boundaries between “musical” and “non-musical” sounds leads to fuzzy segmentations of sound in time. For post-tonal contexts, therefore, it is arguably ill-fitting to assume a generalized concept of formal functions, in which specific musical structures are associated with specific formal-temporal positions within the formal process via a quasi-spatial metaphoric listening. Still, post-tonal sonic elements in most listening situations are perceived in a temporal sequence and usually intuitively related to one another contextually. It is therefore necessary to develop adequate categories that help us grasp such novel conceptualizations of temporal experience and situate them in their historical context.

[1.5] Sciarrino’s creative method, developed since the late 1960s, can be considered a paradigmatic case of composition evoking the experience of time and, not least due to the broad attention it has received and its significant impact on composers of younger generations, deserves particular attention for a general discussion of temporalities in post-tonal music. Sciarrino’s music emerges from succinctly defined musical “figures,” elaborated in detail by the composer himself in written form (Sciarrino 1998; Giacco 2001), that reconcile more conventional elements of discursive organicist design (processes of accumulation, multiplication, and transformation; Sciarrino 1998, 17–96). These figures are often based on continuously varied repetitions of micro-gestures (see Antares Boyle’s contribution to this symposium), with strategies of rupture and formal deterioration that the composer calls “little bang” (short impulses or accents that trigger formal processes) and “window form” (interruptions of various length that intentionally inhibit implied formal developments [Sciarrino 1998, 97–148]). This unique mixing of “linear” and “non-linear” strategies—usually set in easily accessible formal outlines that are based on spatially designed continuity drafts (Utz 2023, 297–304)—is staged in a soundscape of mostly minimal dynamics and reduced activity at the edge of silence, sensitizing the listener toward micro-alterations (see Helgeson 2013): “when the ear is refined towards the threshold of the imperceptible, then this silence seems to explode” (Sciarrino [1995] 2001).(5) A semanticization of the musical material by text-based or dramatic connotations as well as by titles, bodily gestures (heartbeat, trembling, breathing), and a “naturalistic” modeling of environmental sounds (wind, cicadas, radio noise) problematizes and defers the boundaries between musical and everyday experience—establishing “open” beginnings and “open” endings as formal defaults (Utz 2023, 277–294).

[1.6] In this article, I discuss key strategies of Sciarrino’s temporal form based on analytical investigations into three exemplary works that represent different genres and temporal dimensions. This approach takes inspiration from Sciarrino’s conceptualization of form in Anton Webern’s work. The broader context of the perspective taken here is related to an ongoing research project titled Points of Discontinuity. This research aligns with established scholarly work on segmentation, phrasing, and form in post-tonal music (for example Hasty 1981, 1984; Deliège 1989; Cambouropoulos 2001; Hanninen 2004; and Boyle 2018) and emerges from my perception- and performance-informed concept of morphosyntactic musical analysis (Utz 2023). The morphosyntactic approach attempts to closely cross-relate spatial-morphological aspects of perception (gestalt formation and spatialization of events in memory) and temporal-syntactic aspects (transformation or change of musical events or processes in time and their syntactic relationships). More specifically, morphosyntactic analysis approaches these dimensions with a strong focus on the sounding result, along with established methods of score-based analysis, and places particular emphasis on the interaction of morphosyntactic and metaphorical layers of musical meaning, conceiving them as interdependent. Departing from this perspective, the present article aims to explore how micro- and macro-formal layers of musical sound and time cross-influence one another and how “beginnings” and “endings” of different salience and relevance intersect on multiple dimensions of the listening experience.

2. Sciarrino’s Formal Strategies and His Reflections on Webern

[2.1] Musical beginnings and endings cannot be viewed in isolation from musical form as a whole. Situations to which this applies are Sciarrino’s sound structures “at the edge of silence”: in many situations in Sciarrino’s music it remains unclear whether something is being heard at all, whether we are listening to a “pure silence” or rather background noises obstructing or masking the “musical sounds” being heard. This relates Sciarrino’s works to a certain trend in new music around the 1970s and 80s toward silence and stillness, not least emerging from Luigi Nono’s celebrated String Quartet Fragmente, Stille – An Diotima (1979–80). The way in which musical listening is conceived through silence in Nono and Sciarrino, however, has to be clearly differentiated (Carratelli 2006, 59–61): Nono’s emphatic aesthetics of “ascolta!” seeks a comprehensive absorption of the listener into the sounding materiality by isolating short musical events in a radicalized fragment form. On the contrary, Sciarrino’s music re-establishes formal continuities around silences and at the same time challenges the closed space of the musical work by staging near-silent sounds as unstable and ephemeral qualities: “Sound is a kind of window hatched on the silence, and Sciarrino’s music pauses and lingers near this threshold in order to capture what can only be intercepted indirectly” (1998, 60).(6) Sciarrino’s music frequently fosters a listening situation in which the aesthetic difference between the sphere of art and everyday life is minimized. To some degree, this already relativizes the multiple options to stage the beginning, middle, or end of works, which is especially apparent in his open forms that expand into the performance space, such as Il cerchio tagliato dei suoni (1997) for one hundred flutists moving around the audience, or those conceived for outdoor performance such as his La perfezione di uno spirito sottile (1985).(7)

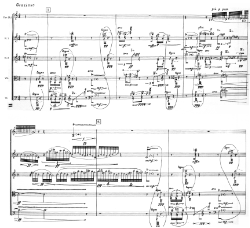

Example 1. Webern, 6 Stücke für Orchester

(click to enlarge)

Example 2. Webern, 6 Stücke für Orchester

(click to enlarge)

Example 3. Webern, 6 Stücke für Orchester

(click to enlarge)

[2.2] Anton Webern’s work can be seen in many respects as a forerunner of such a conception of form that problematizes aesthetic difference—even if such an interpretation may not coincide with the self-image of the composer, who emphatically conceived his work as a continuation of the German-Austrian tradition of discursive formal processuality. When read or heard from the perspective of Sciarrino’s music, however, Webern’s scores reveal numerous “cracks” that let the “world” penetrate into the sphere of art and thus delimit the aesthetic experience. In his book Le figure della musica (1998), Sciarrino offers a short discussion of Webern’s orchestral piece op. 6, no. 4 (1909), a much-analyzed piece that explores the funeral march topic with implicit autobiographical associations (Examples 1–3). Sciarrino points out the startling, unexpected nature of the piece’s ending in which the instrumentation of the beginning, limited to the percussion apparatus, returns (mm. 1–7 vs. 40–41, Examples 1 and 3)—but now in a crescendo leading into fff, which creates a maximum difference to the barely audible ppp of the beginning. In between these two framing events, however, there is no linear unfolding; according to Sciarrino, the “rhetoric of the accumulation process” in this piece is used in a manner that avoids a straightforward, predictable process. In the middle of the piece, Sciarrino hears “a desolate landscape whose muffled echo, whose metallic hint of threatening rot accumulates more tension than the sound accumulation leading to the climax [at the end of the piece]” (1998, 55).(8) Indeed, an “organic” formal process is repeatedly interrupted in the middle of the piece by silences, during which only the uninterrupted ostinato figures of the percussion apparatus remain audible—providing a point of departure for Sciarrino’s window form (mm. 16–19, 29, 30.2–31, 34, Example 2). Thus the intensification at the end appears somewhat unmotivated and, seemingly as a consequence of this, the final climax is abruptly cut off. Sciarrino diagnoses an “irregularity in the processes, that is, a disappointment in our expectations”(9) (1998, 55), a hint at Sciarrino’s evident preference for unresolved open endings that somehow contradict those organicist processes that frequently seem to establish within his macroforms.

[2.3] Sciarrino’s semanticized reading of Webern is transformed in his own works into an intentionally naïve way of word- and tone-painting, a symbolically informed musical “naturalism” that Sciarrino has repeatedly defended in his writings, especially in Le figure della musica. More specifically, Sciarrino’s Webern reveals two aspects which are of immediate relevance to our discussion: the semanticization of formal processes (the “metallic hint of threatening rot”), avoiding a reference to Webern’s own more idyllic semantic associations (Johnson 1999, 99–127), and highlighted failed expectations and discontinuities, marking the point of departure for his reimagination of conventional formal functions. The idea of a semanticized rupture can be understood as the composer’s particularly crucial strategy of working against a tendency of his own formal designs toward continuity, toward simple progressive arch forms that would tend to fade in and fade out in the manner of a linear intensity curve if left unmodified. Although of course differently marked and unmarked types of endings occur in different works, my preliminary studies demonstrate a clear tendency in works of the 1980s and 90s to particularly mark their endings by something enigmatic, symbolizing a remainder, an unresolved difference, a question mark—a strategy that aims to reveal different points of meaning for each individual work despite the considerable similarity of their musical material and formal design (Utz 2023, 277–94).

3. Three Case Studies: Sciarrino’s Beginnings and Endings as Reflections (and Consequences) of a Semanticized Macroform

[3.1] The three case studies that follow have been chosen for their different perspectives on how beginnings and endings relate to macroformal process and implicit or explicit semantic layers. They differ in genre, duration, density, and in historical period. The Quintettino no. 1 (1976) for clarinet and string quartet lasts less than three minutes and is characterized by an almost uninterrupted continuous high density. Efebo con radio (1981) is a work for female voice (speaking and singing) and orchestra of medium length and changing density resulting from the collage-like character in which repeatedly familiar idioms of (radio broadcast) music and speech surface. Da gelo a gelo (2006), finally, is a dramatic work based on the diary of the female Heian-period Japanese poet Izumi Shikibu. This work bears the subtitle “100 scene con 65 poesie” (“100 scenes with 65 poems”) which points to its highly fragmented organization into 100 scenes that together last about 110 minutes, making it one of Sciarrino’s longest works.

[3.2] The following analyses explore the interdependence of total duration, degrees of density, and the types of beginnings and endings introduced on global and local levels. The concept of “density” might be associated with closely interrelated (though surely not synonymous) concepts such as “entropy” and “tension,” originating in postwar information aesthetics (see Borio 2005; Iverson 2019, 110–138) and early twentieth-century energetics respectively (see Rothfarb 2002; BaileyShea and Monahan 2018). For present purposes, I pursue a pragmatic approach to these musical dimensions by identifying degrees of density in the music according to such analytical findings as the homophonic unity or polyphonic independence of voices, their rhythmic and dynamic simplicity and complexity, as well as the overall impression of structural uniformity or multiplicity. Naturally, such categories are context-sensitive and must always be adjusted to the style or “tone” of a musical work: in a reduced structure consisting of single tones (e.g., Feldman or Scelsi) the addition of a second tone might already indicate intensifying density, whereas such a dyad could be conceived as reducing the musical structure to extremely low density, or function as a caesura, in a highly complex stylistic context (e.g., Carter or Ferneyhough). An interdependence between duration, density, and different types of beginnings and endings is evident when considering, for example, that a “sudden,” unexpected ending (possibly additionally perceived as “marked,” i.e., clearly audibly indicated, and “open,” i.e., perceived as on-going with music virtually “continuing” into post-musical silence) may have a profoundly different impact in very short and medium-length pieces respectively, while their perceptual effect may also strongly vary according to differing preceding density states.

[3.3] Evidently, many such gradations may occur in combination or remain ambivalent. One could, for instance, remain undecided about whether a specific fadeout at the end of a piece may be perceived as an “open” or a “closed” ending, or whether a discontinuous “breaking-off” is heard as a marked closure or rather as an unmarked, contingent “stopping.” Regarding such ambivalences, it can be said that there is hardly any form of ending that a posteriori may not take on some form of implied intentionality conceived as “marked” by a sensitive listener, calling into question whether an “unmarked” ending is a useful category at all. It seems most suitable for listening situations in which the end of a listening process is determined by the listener themselves or by a third party: fadeout of a pop song on the radio, spontaneous exit from a sound installation, fading in and out in a situationally conceived performance that enables spatial participation of the recipient, etc. This article’s conclusion (see section 4) summarizes the analytical results in light of some of these permeable categories.

Quintettino no. 1 (1976) for Clarinet and String Quartet

Example 4. Sciarrino, Quintettino no. 1,

(click to enlarge)

Example 5. Sciarrino, Quintettino no. 1,

(click to enlarge and see the rest)

Example 6. Sciarrino, Quintettino no. 1,

(click to enlarge)

Audio Example 1. Sciarrino, Quintettino no. 1, mm. 1–12, 31–62. Salvatore Sciarrino, Musique de chambre, CD Arion, 2005; Michel Lethiec (clar.), Boris Garlitsky (vl.), Sabine Lethiec (vl.), Wladimir Mendelssohn (vla.), Alain Meunier (vc.), https://youtu.be/ZD9Yuxwa9sQ

[3.4] In the 1970s, Sciarrino developed idiosyncratic virtuosic idioms for piano, strings, and wind instruments that were systematically explored and expanded in solo as well as ensemble works. The violin techniques documented in the Sei capricci for solo violin (1976) departed from Niccolò Paganini’s Capricci op. 1 (printed 1820) and were dedicated to the violinist Salvatore Accardo, who since the 1960s had been well-known for his Paganini performances (Drees 2019). Sciarrino’s Capricci build on a gestural and iconographic approach to virtuosity: a performance technique emerging from a radicalized understanding of established virtuosic playing movements—an approach related to Helmut Lachenmann’s concept of musique concrète instrumentale. An alienation of conventional virtuosity is achieved in part by a continuous, often exclusive, use of harmonics, resulting in unstable pitch and a strong impact of noise components on the sound result. Pieces such as the Quintettino no. 1 transfer these techniques to chamber music situations. The works of this period, as Pietro Misuraca explains, “skillfully play with the listener’s expectations through established and suspended symmetries, broken and restored balances, predictability and unpredictability (2008, 45).(10) Quintettino no. 1 (Examples 4–6, Audio Example 1), with a total duration of 2:46 in the available recording,(11) is clearly organized in two parts (mm. 1–36/37–62), with the second part marked by a change of tempo (“Prestissimo impazzando” [“mad” prestissimo], in contrast to the “Grazioso” of the first part) and texture. The musical material of the string quartet in the first part is restricted to virtuosic micro-gestures using (natural and artificial) harmonics exclusively, changing between shorter and longer trills, tremoli, and arpeggi, while the second part is dominated by repeated pitches in a sixteenth-note tremolo (still using harmonics exclusively, resulting in four-voiced chords) and arpeggiating figures. The clarinet similarly acts at the boundaries of pitched and non-pitched timbres, often merging closely with the strings, but in the second part, especially owing to its non-synchronicity with the strings’ regular pulse, it also emerges somewhat as a solo part.

[3.5] Generally the structure, compared to Sciarrino’s later works, exhibits a kind of horror vacui, resulting in the impression of a continuous high density, especially in the first part. The unified sound quality of the entire piece, owing to this structural density, is obvious, and even the change in texture in the second part, evident when reading the score, does not necessarily constitute a strong cue for the listener (Audio Example 1). Still, this reduction of density in the second part retrospectively might be interpreted as a preparation of the quasi-cadential ending, an ending that is quite obviously approached by a continuously intensifying dynamics and expanding pitch range. Given Sciarrino’s intention to sensitize his listeners toward the tiniest details, we can posit at least for the ending a rather clearly marked formal function that even alludes to a tonal cadence (Example 6): the accented rhythm terminates the preceding ostinato structure and the clarinet’s concluding glissando further contributes to singling out this ending as a unique moment.

[3.6] This moment is preceded by a somewhat less salient marker at the end of the first part in the clarinet’s long sustained multiphonic double D4 that, especially because of its long duration, clearly marks a moment of closure, although this does not at all affect the strings’ structure, which continues unabated (Example 5). These marked endings contrast with the unmarked beginning, which appears to simply “start” in medias res without presenting any familiar kind of initiating gesture (Example 4), possibly provoking uncertainty about where the first note of the music has been heard (especially in a concert situation where it might be masked by environmental noise). Thus the formal process may be described as an almost deterministic process from an indefinite beginning to increasingly clearly marked endings, maybe even implying some sort of irony given the endings’ apparently conventional cadential function.

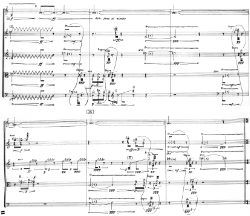

Efebo con radio (1981) for Voice and Orchestra

Example 7. Sciarrino, Efebo con radio, mm. 1–4

(click to enlarge and see the rest)

Example 8. Sciarrino, Efebo con radio,

(click to enlarge)

Example 9. Sciarrino, Efebo con radio,

(click to enlarge)

Audio Example 2. Sciarrino, Efebo con radio, mm. 1–18, 46–48, 185–196 Salvatore Sciarrino, Storie di altre storie, CD Winter & Winter 2008, Sonia Turchetta (voice), WDR Sinfonieorchester Köln, Kazushi Ono (conductor), recording 2005, https://youtu.be/JY_C_nYt7lQ

[3.7] An ironic media-archeological approach to form is evident in Efebo con radio (Ephebe with Radio) for female voice (speaking and singing) and orchestra (Examples 7–9, Audio Example 2). In this case, the irony extends into semantic and even autobiographical layers of meaning: the work is inspired by the radio experiences of the young Sciarrino during the early 1950s.(12) Like the Quintettino no. 1, this approximately eleven-minute work is characterized by a rarely interrupted continuity with a foregrounded noise timbre, basically produced by the same string techniques we found in the Quintettino (here symbolizing the noise typical for analog radio reception), adding translucent scraps of musical quotations (including Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy’s violin concerto, American and Italian popular music, and the signature tune of an Italian radio program(13)) as well as Italian radio speech including traffic news (spoken by the [live] vocalist who also contributes several of the musical quotations) (see Drees 2013 for a detailed analysis). Sciarrino relates his media-archeological approach to Stockhausen’s montage-like electronic music Hymnen (1966–67).(14) Indeed, the principle of montage is fundamental to Sciarrino’s concept of form in general. The idea of “window form” is multiply indebted to Stockhausen’s “moment form” (Stockhausen [1960] 1963) and its application to a work like Kontakte (1959–60), which is described by Sciarrino as a montage, in which “the contiguity of the blocks produces immense leaps of environment: there is a wealth of information, even traumatic, in the abrupt transition from one sound world to another. Furthermore, related and non-contiguous blocks connect in memory, create a polyphony of relationships through intermittence” (1998, 122).(15) Sciarrino’s tendency toward temporal continuity becomes particularly evident in his rethinking or revision of Stockhausen’s montage principle that aimed at isolating “moments” by repeated discontinuities, expanded by Kramer to “moment time,” in which “nonlinear relations (or lack thereof) between segments of the mosaic are essential to the structure” (Kramer 1988, 220). The heterogeneity of Sciarrino’s material in Efebo con radio becomes audible only to a limited extent and is integrated in a noise-saturated continuous texture. This makes it clear that while Sciarrino’s interruptive strategies of “window form” do contribute to a broad tendency toward presentist time concepts in new music emerging before, around and after Stockhausen’s “moment form” and arguably culminating in Nono’s String Quartet (Utz 2023, 343–51), the ultimate aim of his works might be seen in embedding such discontinuities in a web of “pseudo-causal” relationships that enable the listener to productively activate memory and interconnect events in time.

[3.8] This principle becomes most evident at the end of Efebo con radio. The sound stream here is interrupted abruptly by a final “window” featuring the “radio announcer,” impersonated by the live female singer, who provides information on the piece just heard: “we have just transmitted from Salvatore Sciarrino ‘Efebo con’ [cut]” (“di Salvatore Sciarrino abbiamo trasmesso: ‘Efebo con’ [troncare],” m. 194; see Example 9). This dry moderation relates to a previous text passage about descriptive work titles in music during which the orchestral continuum is similarly interrupted(16) (m. 48, Example 8), creating multi-level self-reflexivity (Drees 2013, 344). This analogy may likely motivate one to assume a formal organization in two unequal parts here again, although this first interruption occurs rather early on, after less than one quarter of the piece’s total duration (2:35–2:47 of a total duration of 11:20 in the recording).(17) Arguably this moment constitutes the only salient change in texture despite a very heterogeneous quality of the musical surface quite unlike that of the Quintettino. In contrast, the multiple repetitions of previous material (mm. 164–93 = 4–33, mm. 53–64 = 37–48; see Drees 2013, 344) arguably do not materialize as salient cues for the listening comprehension owing to the continuous, flowing, and transformational character of the music; indeed, they may go unnoticed for most uninformed listeners.

[3.9] The beginning of Efebo con radio appears unmarked and incidental as in the Quintettino (Example 7)—but here this forms an analogy to the abrupt closing of the piece after the interrupted announcement in the end (the tremolo of a metal plate is quickly fading out, see Example 9). This suggests an analogy to the real-life activity of switching on and off the radio.(18) On the one hand, if one assumes particularly well-informed listeners who are aware of the title of the work and who actually interpret the sounding scraps of quotation as radio excerpts, this ending may appear very consequential. On the other hand, the point of this ending is of course that it reveals the meaning of what has been heard retrospectively, thus making explicit the “radiophonic” form of the entire work. The autobiographical and anecdotical character of Efebo con radio makes a layer of Sciarrino’s compositions particularly recognizable, which is inherent in almost all of his works in one way or another: they describe or resonate with different levels of listening impressions of the compositional subject and/or—in music theater—of the characters acting on the stage. They are sounding the imagined, unsounded auditory perceptions in the minds of real or imagined subjects and thus temporarily take on diegetic qualities.

Da gelo a gelo [Kälte]. 100 scene con 65 poesie (2006)

Example 10. Sciarrino, Da gelo a gelo, scene 1 (Prologo), mm. 1–2

(click to enlarge)

Example 11. Sciarrino, Da gelo a gelo, scene 30, mm. 13–18

(click to enlarge)

Example 12. Sciarrino, Da gelo a gelo, scene 100, mm. 15–19

(click to enlarge)

Example 13. Sciarrino, Da gelo a gelo, scene 9, mm. 1–12

(click to enlarge)

Audio Example 3. Sciarrino, Da gelo a gelo, scene 1, mm. 1–7 (Ex. 4a), scene 9, mm. 1–12 (Ex. 4d), scene 30, mm. 13–27 (Ex. 4b), scene 100, mm. 12–19 (Ex. 4c). Izumi: Anna Radziejewska, soprano; La nutrice del principe/ la cameriera di Izumi: Ulrike Mayer, mezzo-soprano; Il paggio di Izumi: Felix Uehlein, countertenor; Il paggio del principe: Michael Hofmeister, countertenor; Il principe: Otto Katzameier, baritone; Radio-Sinfonieorchester Stuttgart SWR; Tito Ceccherini, conductor. Live recording, Schwetzingen 23/03/2006. https://youtu.be/V68LjTjO9Yg

[3.10] The impression that the music we hear is actually heard by (or sounding inside of) the characters on stage is very obvious in Da gelo a gelo (Examples 10–13, Audio Example 3). We hear abstracted allusions to the sounds of crickets, birds, rain, wind, and storms, but mostly we hear the long and uneventful silence of aimless waiting. Sciarrino’s “naturalism” achieves an ideal form of materialization as a finely calibrated tool of psychological musical agency in the context of his dramatic works, in which sounds evoked by plot, sung text, or dramatic context are ubiquitous. Reaching beyond naïve forms of diegetic music, the sonorous focus on the bodies and minds of the performers on stage establishes a close connection between Sciarrino’s dramatic works and his instrumental music with its emergence from sounding bodily and psychic states.

[3.11] Sciarrino has developed a unique form of psychological music theater since Lohengrin (1982–83), Luci mie traditrici (1996–98), and Infinito nero (1998), in which “dramatic” action and indeed any kind of realistic plot are reduced or completely abandoned. In the music-dramatic context, this reduction forms an essential part of the composer’s quoted intention to “refine the ear towards the threshold of the imperceptible.” Even compared to the partly radical reduction of means in earlier dramatic works, with Infinito nero marking a particular extreme form of anti-dramatic, introspective stasis (see Leydon 2012), Da gelo a gelo provides an especially interesting example in the present context owing to its highly fragmented form, alluded to in the subtitle: it consists of 100 short scenes in which 65 poems—as well as other “prose” texts—are set, derived from the diary with integrated poems (1002/03 CE) of the poet and court lady Izumi Shikibu, describing her unhappy relationship to Prince Atsumichi (see Samonà 2018, 89–98 for a basic outline of the work). While the reworking of the existing text material through reduction to short essential phrases—a technique that further tightens the terse character of the Japanese originals—is familiar from Sciarrino’s other dramatic works, the musical fragmentation into 100 short scenes is a new feature introduced in this work, aiming at a pronounced destabilization and suspension of linear time by adopting a loose diary-like structure as a model for organizing music-theatrical form. The title (“From Coldness to Coldness”) alludes to the contemplation of cyclicity in nature and the seasons (Sciarrino 2006), a theme of primary importance in traditional Japanese aesthetics. The autumn is repeatedly alluded to and the melancholy associated with it permeates the entire work, translating the diary’s “lament of hardly ever satisfied longing” (Benl 1965, 9).(19)

[3.12] The transfer of the diary-like principle to musical form resulting in a radicalized montage character is somewhat implicit also in the two pieces already discussed. It connects Da gelo a gelo to a considerable corpus of fragment form models in new music since the 1970s, including works by Luigi Nono, György Kurtág, and Wolfgang Rihm (Metzer 2009, 104–43). However, Sciarrino arguably aims at quite a different consequence compared to the expression-saturated aesthetics of those composers. Certainly, the sequence of scenes in Da gelo a gelo generally does not appear in any way interconnected or dramatized (quite in contrast to the almost deterministic order of the scenes in Luci mie traditrici), with one important exception: in scenes 30 and 100 (the last scene), the Prince’s nurse enters the stage and obstructs the Prince’s relationship with the poet-courtesan (Examples 11 and 12). Significantly, the music of these two scenes builds an “architectonic” bridge with no. 1, the instrumental “Prologo” (Example 10). All three scenes share an agitated and energetic texture, dominated by densely interwoven layers and repeated noise-permeated sonorities (Audio Example 3). Taking into account that these three scenes together constitute only a small percentage of the work’s total duration as well as the considerably low density and contemplative character of almost the entire remaining 97 scenes, it becomes clear that the architectonic staging of beginning, middle, and end receives particular significance in this conception of form.(20)

[3.13] Unlike conventional formal functions, however, these three scenes do not appear as consequences (or triggers) of a processual time but rather constitute moments of blatant and disrupting discontinuity. As is typical in Sciarrino, this can be interpreted semantically: the sudden and (considering the “inner” plot) disastrous ending of scene 100 is foreshadowed not only in the two earlier scenes 1 and 30 but also (implicitly) in several other moments of the music. This lends an atmosphere of diffuse threat to the entire work, an atmosphere that Sciarrino conjures in many preceding works (including most notably Introduzione all’oscuro for twelve instruments [1981] and Luci mie traditrici).(21)

[3.14] With regard to the continuous re-working of the minimized material one might argue that the texture of scenes 1, 30, and 100 contains most if not all of the material employed in the entire work, so that all sounds heard in the predominantly quiet and “lyrical” scenes 2–29 and 31–99 can be understood as echoes of, or precursors to, those three “tragic” moments. For example, the quick repetitions of noise-permeated sonorities in the highest registers in several scenes recur as symbols of cricket sounds (which also appear in Luci mie traditrici), as in scene 9 (Example 13). And the particular figures that constitute Sciarrino’s omnipresent vocal style, sillabazione scivolata (see Saxer 2008), are adopted in the instrumental parts of these three pivotal scenes throughout, although somewhat disguised by the dense polyphony of layers. Thus, beginning, middle, and end seem to summarize the lengthy process of the music in a particularly condensed manner, without in any way functioning as consequences of a formal necessity. Understood as integrated echoes and precursors of the musical material, they might be interpreted “organically,” as origin and conclusion of the musical narrative; understood instead as unprepared interruptions, though, they stand as erratic physical markers outside of the general tone in which the opera is set.

4. Conclusion: Reinventing Conventional Formal Functions

[4.1] It appears that all three strategies explored in the above case studies contain references to conventional form-functional elements, though these elements are entirely recontextualized and reimagined. In Quintettino no. 1 the final “cadence” is approached almost deterministically and staged by several marked elements that indicate closure. Still, the uninterrupted high density and the compressed duration of the piece let the ending appear somewhat abrupt and unpredictable. The supposed conventional functionalities of closing formulas (anticipated by the clarinet at the end of the first part) appear as ironic historical references rather than consequences of the musical structure. Heard from this perspective, this potentially conventional ending may appear like an arbitrary interruption of a non-linear and undirected musical flow.

[4.2] The idea that the composer enters the musical stage with a tongue-in-cheek comment at the end can be traced back to a number of famous open endings in music history including Franz Schubert’s Winterreise (1827) and Robert Schumann’s Kinderszenen (1838) (Utz 2020, 338–43). Sciarrino’s Efebo con radio aligns with this tradition by staging autobiographical experience in a media-archeological acoustic framework, unmasking the implicit self-reflexive narrative only at the very end, lending it the connotation of a “key” to the entire work. At the same time, the changing density and the collage character of the music let the ending (again anticipated by a similar earlier discontinuity) appear abrupt and discontinuous, connecting it to the equally unmediated beginning.

[4.3] While the continuing variation of restricted musical material and the high speed of changing events in these two earlier examples establish a temporal flow and thus, following Kramer’s definitions (1988, 20–65), largely constitute examples of (nondirected) linear, rather than non-linear, time (which makes their discontinuities all the more startling), Da gelo a gelo clearly pursues a spatialized, architectonic formal idea in which the discontinuous “pillars” of scenes 1, 30, and 100 disrupt an extended contemplative, non-dramatic, and fragmented musical situation with linear time largely absent. Like a major part of his instrumental music since the 1980s, this “low-information strategy” provokes a “memory sabotage” (Snyder 2000, 234–38) in the listener with the effect that beginning, middle, and end might occur as particularly memorable points of an otherwise ungraspable concept of expanded non-linear time.

[4.4] The work’s long duration clearly reveals how Sciarrino works against the kind of seemingly self-regulating, “cybernetic” form that is evident in many of his chamber music works of the 1980s (see Utz 2023, 294–95). This strategy relies on the model of energetic chains of cause and effect and suggests the perception of interruptions or “little bangs” as triggers of the formal process. In Da gelo a gelo, on the contrary, the three violent outbursts stand out for their lack of consequences and erratic isolation. As a result, they fail to have an impact through which a sensitive listener might understand them as effects of a cause or a cause with effects. Thus, the ending, although clearly marked by one of these outbursts, in no way completes a trajectory or fulfills an expectation. Rather, the arbitrary completion of the one hundredth scene is taken as an external, purely rational motivation for cutting off the music, possibly implying, in the tradition of the open ending in Alban Berg’s Wozzeck, that the musical-dramatic conflicts remain unresolved (see Utz 2020, 330–31).

[4.5] The semanticization of his material (as evident in his interpretation of Webern as well as a large number of other composers and artists he refers to in his writings) offers Sciarrino great flexibility in reinventing, suspending, or enhancing temporal functions in his music. In the context of 20th- and 21st-century musical approaches to form, this phenomenological and psychological approach develops a particularly broad spectrum of options to interconnect musical microform and macroform based on a reinvention of conventional formal functions. This reveals Sciarrino as a composer whose conception of music perception is not restricted to psychological dimensions but extends to the areas of socio-political context, cultural memory, and the “ecological” listening experience. His works provide a particular wealth of examples for a tradition-pervaded composition in which the familiar appears unfamiliar and the seemingly obsolete is revealed as illuminating.

Christian Utz

University of Music and Performing Arts Graz

Leonhardstr. 15, 8010 Graz

christian.utz@kug.ac.at

Works Cited

Adorno, Theodor W. 1970. Ästhetische Theorie. Suhrkamp.

—————. 1971. Philosophie der neuen Musik. Suhrkamp.

—————. 2002. Aesthetic Theory. Translated by Robert Hullot-Kentor. Continuum.

—————. 2006. Philosophy of New Music. Translated by Robert Hullot-Kentor. University of Minnesota Press.

Agawu, Kofi. 1991. Playing with Signs: A Semiotic Interpretation of Classical Music. Princeton University Press. https://doi.org/10.1515/9781400861835.

Aringer, Klaus, Franz Karl Praßl, Peter Revers, and Christian Utz, eds. 2017. Geschichte und Gegenwart des musikalischen Hörens: Diskurse—Geschichte(n)—Poetiken. Rombach.

Arndt, Matthew. 2018. “Form—Function—Content.” Music Theory Spectrum 40 (2): 208–26. https://doi.org/10.1093/mts/mty024.

BaileyShea, Matthew, and Seth Monahan. 2018. “‘Von anderem Planeten?’ Gesture, Embodiment, and Virtual Environments in the Orbit of (A)Tonality.” In Music, Analysis and the Body: Experiments, Explorations, and Embodiments, ed. Nicholas Reyland and Rebecca Thumpston, 31–50. Peeter. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv1q26wr0.10.

Benl, Oscar. 1965. “Vorwort.” In Der Kirschblütenzweig: Japanische Liebesgeschichten aus tausend Jahren. Edited and translated by Oscar Benl, 7–14. Nymphenburger Verlagshandlung.

Borio, Gianmario. 1993. Musikalische Avantgarde um 1960: Entwurf einer Theorie der informellen Musik. Laaber.

—————. 2005. “Komponisten als Theoretiker: Zum Stand der Musiktheorie im Umfeld des seriellen Komponierens.” In Musiktheoretisches Denken und kultureller Kontext, ed. Dörte Schmidt, 247–74. Edition Argus.

Boyle, Antares Leah. 2018. “Formation and Process in Repetitive Post-Tonal Music.” PhD diss., University of British Columbia. https://open.library.ubc.ca/cIRcle/collections/ubctheses/24/items/1.0371135.

Cambouropoulos, Emilios. 2001. “Melodic Cue Abstraction, Similarity, and Category Formation: A Formal Model.” Music Perception 18 (3): 347–70. https://doi.org/10.1525/mp.2001.18.3.347.

Caplin, William E. 2009. “What are Formal Functions?” In William E. Caplin, James Hepokoski, and James Webster, Musical Form, Forms & Formenlehre: Three Methodological Reflections, ed. Pieter Bergé, 21–40. Leuven University Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt9qf01v.5.

Carratelli, Carlo. 2006. “L’integrazione dell’estesico nel poietico nella poetica post-strutturalista: Il caso di Salvatore Sciarrino, una ‘composizione dell’ascolto.’” PhD diss., Università degli Studi di Trento/Université de Paris IV, Sorbonne. https://www.salvatoresciarrino.eu/Tesi/Tesi_Carratelli.pdf.

Deliège, Irène. 1989. “A Perceptual Approach to Contemporary Musical Forms.” Contemporary Music Review 4 (1): 213–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/07494468900640301.

Drees, Stefan. 2013. “Zur (Re-)Konstruktion kultureller Räume im Schaffen Salvatore Sciarrinos.” Die Tonkunst 7 (3): 340–49.

—————. 2019. “Orientierung an der ‘Logik des Körpers’: Zu einem zentralen Aspekt von Salvatore Sciarrinos ‘Sei Capricci per violino’ (1975/76).” In Salvatore Sciarrino (Musik-Konzepte Sonderband), ed. Ulrich Tadday, 97–117. edition text + kritik.

Giacco, Grazia. 2001. La notion de “figure” chez Salvatore Sciarrino. L’Harmattan.

Hanninen, Dora A. 2004. “Associative Sets, Categories, and Music Analysis.” Journal of Music Theory 48 (2): 147–218. https://doi.org/10.1215/00222909-48-2-147.

Hasty, Christopher F. 1981. “Segmentation and Process in Post-Tonal Music.” Music Theory Spectrum 3 (1): 54–73. https://doi.org/10.2307/746134.

—————. 1984. “Phrase Formation in Post-Tonal Music.” Journal of Music Theory 28 (1): 167–90. https://doi.org/10.2307/843531.

Helgeson, Aaron. 2013. “What Is Phenomenological Music, and What Does It Have to Do with Salvatore Sciarrino?” Perspectives of New Music 51 (2): 4–36. https://doi.org/10.1353/pnm.2013.0001.

Irving, Howard. 1985. “Haydn and Laurence Sterne: Similarities in Eighteenth-Century Literary and Musical Wit.” Current Musicology 40: 34–49.

Iverson, Jennifer. 2019. Electronic Inspirations: Technologies of the Cold War Musical Avant-Garde. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780190868192.001.0001.

Johnson, Julian. 1999. Webern and the Transformation of Nature. Cambridge University Press.

Kramer, Jonathan D. 1988. The Time of Music: New Meanings, New Temporalities, New Listening Strategies. Schirmer.

Leydon, Rebecca. 2012. “Narrativity, Descriptivity, and Secondary Parameters: Ecstasy Enacted in Salvatore Sciarrino’s Infinito Nero.” In Music and Narrative since 1900, ed. Michael L. Klein and Nicholas Reyland, 308–28. Indiana University Press.

Ligeti, György. [1960] 1965. “Metamorphoses of Musical Form.” die Reihe 7: 5–17.

Metzer, David. 2009. Musical Modernism at the Turn of the Twenty-First Century. Cambridge University Press.

Misuraca, Pietro. 2008. Salvatore Sciarrino: Itinerario di un alchimusico. Unda Maris.

Neubacher, Jürgen. 1986. Finis coronat opus: Untersuchungen zur Technik der Schlußgestaltung in der Instrumentalmusik Joseph Haydns, dargestellt am Beispiel der Streichquartette. Schneider.

Rothfarb, Lee. 2002. “Energetics.” In The Cambrdige History of Western Music Theory, ed. Thomas Christensen, 927–55. Cambridge University Press.

Samonà, Clara. 2018. “Salvatore Sciarrinos La porta della legge: Fast ein kreisender Monolog nach Franz Kafka. Eine Untersuchung zum Musiktheaterwerk und zur Rezeption.” PhD diss., University of Heidelberg. https://archiv.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/volltextserver/28801.

Saxer, Marion. 2008. “Vokalstil und Kanonbildung: Zu Salvatore Sciarrinos ‘Sillabazione scivolata.’” In Musiktheater der Gegenwart: Text und Komposition, Rezeption und Kanonbildung, ed. Jürgen Kuhnel, Ulrich Mueller, Oswald Panagl, and Gernot Gruber, 475–85. Mueller-Speiser.

Sciarrino, Salvatore. [1995] 2001. “Soffio e forma.” In Carte da suono (1981–2000), ed. Dario Oliveri, 171. CIDIM.

—————. 1998. Le figure della musica: Da Beethoven a oggi. Ricordi.

—————. 2006. “Da gelo a gelo (Kälte): 100 scene con 65 poesie. Nota dell’autore.” https://www.salvatoresciarrino.eu/data/composition/eng/199.html.

Snyder, Bob. 2000. Music and Memory: An Introduction. The MIT Press.

Stockhausen, Karlheinz. [1960] 1963. “Momentform: Neue Beziehungen zwischen Aufführungsdauer, Werkdauer und Moment.” In Aufsätze 1952–1962 zur Theorie des Komponierens, ed. Dieter Schnebel, 189–210. Vol. 1 of Texte zur Musik. DuMont.

Thorau, Christian, and Hansjakob Ziemer, eds. 2019. The Oxford Handbook of Music Listening in the 19th and 20th Centuries. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190466961.001.0001.

Utz, Christian. 2020. “Zur Poetik und Interpretation des offenen Schlusses: Inszenierungen raum-zeitlicher Entgrenzung in der Musik der Moderne.” Die Musikforschung 73 (4): 324–54. https://phaidra.kug.ac.at/o:125810.

—————. 2023. Unerhörte Klänge: Zur performativen Analyse und Wahrnehmung posttonaler Musik und ihren historischen Voraussetzungen. Studien und Materialien zur Musikwissenschaft, vol. 125. Olms. https://doi.org/10.25366/2023.151.

Webster, James. 1991. Haydn’s “Farewell” Symphony and the Idea of Classical Style: Through-Composition and Cyclic Integration in His Instrumental Music. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511552434.

Discography

Discography

Sciarrino, Salvatore. 2005. Quintettino no. 1 (1976). CD Musique de chambre, Arion; Michel Lethiec (clar.), Boris Garlitsky (vl.), Sabine Lethiec (vl.), Wladimir Mendelssohn (vla.), Alain Meunier (vc.). https://youtu.be/ZD9Yuxwa9sQ.

—————. 2006. Da gelo a gelo (2006). Izumi: Anna Radziejewska, soprano; La nutrice del principe/la cameriera di Izumi: Ulrike Mayer, mezzo-soprano; Il paggio di Izumi: Felix Uehlein, countertenor; Il paggio del principe: Michael Hofmeister, countertenor; Il principe: Otto Katzameier, baritone; Radio-Sinfonieorchester Stuttgart SWR; Tito Ceccherini, conductor. Live recording, Schwetzingen 23/03/2006. https://youtu.be/V68LjTjO9Yg.

—————. 2008. Efebo con radio (1981). Sonia Turchetta (voice), WDR Sinfonieorchester Köln, Kazushi Ono (conductor). Recorded in 2005. CD Storie di altre storie, Winter & Winter. https://youtu.be/JY_C_nYt7lQ.

Footnotes

* This article resulted from research pursued in the three-year research project, Points of Discontinuity: Theory, Categorization, and Perception of Cadences and Openings in Post-tonal Music (PoD), supported by the Austrian Science Fund FWF (01/03/2021–29/02/2024, P 34097-G), https://pod.kug.ac.at. I am grateful for input received from Antares Boyle, Robert Hasegawa, and Mingyue Li as well as two reviewers.

Return to text

1. “Daß das den Kunstwerken versagt ist, daß sie so wenig mehr sterben können wie der Jäger Gracchus, verleiben sie sich als Ausdruck von Grauen unmittelbar ein. Die Einheit der Kunstwerke kann nicht das sein, was sie sein muß, Einheit eines Mannigfaltigen: dadurch, daß sie synthesiert, verletzt sie das Synthesierte und schädigt an ihm die Synthesis” (Adorno 1970, 221).

Return to text

2. “Es rechnet zu den auffälligsten Merkmalen von Schönbergs Spätstil, daß er keine Schlüsse mehr zuläßt. Harmonisch gibt es ohnehin seit der Auflösung der Tonalität keine Schlußformeln mehr. Nun werden sie auch in der Rhythmik beseitigt. Immer häufiger fällt das Ende auf den schlechten Taktteil. Es wird zum Abbrechen” (Adorno 1971, 126).

Return to text

3. “Eine Art ‘Pseudokausalität’

Return to text

4. “una ‘composizione dell’ascolto’” (Carratelli 2006, subtitle).

Return to text

5. “

Return to text

6. “Il suono è una sorta di finestra schiusa sul silenzio, e la musica di Sciarrino sosta e s’intrattiene in prossimità di questa soglia per catturare ciò che non può essere intercettato che indirettamente.”

Return to text

7. These works are discussed in some detail by Mingyue Li’s article in this symposium, which also focuses on the deferred boundaries between musical and “ecological” worlds.

Return to text

8. “

Return to text

9. “La tensione deriva dalla irregolarità dei processi, cioè da una delusione delle nostre attese, delle attese instaurate dal compositore in chi ascolta

Return to text

10. “organizzazioni formali giocano abilmente, attraverso simmetrie instaurate e contraddette, equilibri infranti e ripristinati, prevedibilità e imprevedibilità, con le aspettative dell’ascoltatore.”

Return to text

11. Sciarrino 2005.

Return to text

12. According to the composer, the piece “realizes an exploration of the repertoire of radio broadcasts in Italy between 1951 and about ’54. . . . When I was a child I played with the radio, it was an electronic sound generator, rudimentary but quite rich. The broadcasts were very noisy. What a melancholy, when the modern is so poured out on our backs. But the composition also appears ironic. Where is the irony? In the awareness that the imitation of reality is illusory.” (Sciarrino 1998, 118, “effettua una ricognizione sul repertorio delle trasmissioni radio in Italia, tra il 1951 e il ’54 circa

Return to text

13. The quoted titles include “Second Hand Rose” (1921; music: James F. Hanley, lyrics: Clarke Grant, mm. 132–42), “It had to be you” (1924; music: Isham Jones, lyrics: Gus Kahn, mm. 15–16, 175–76), and a fragment of “Les Bijoux” (Drees 2013, 342).

Return to text

14. One part of Stockhausen’s work also exists in a version for electronics and orchestra (Hymnen (dritte Region), 1969). However, Sciarrino refers to the beginning of Stockhausen’s electronic version (1966–67) in his book Le figure della musica (1998, 117–18) and connects this discussion with his Efebo con radio. He emphasizes that (in contrast to his Efebo) “Stockhausen captures the reality of his time with disused devices. I find this contradiction is genuinely tasty and in keeping with our theme, the space-time discontinuity.” (Ibid., 118; “Stockhausen capta la realtà del suo tempo con apparecchi in disuso. Trovo sinceramente gustosa tale contraddizione e consona al nostro tema, la discontinuità spazio-temporale.”)

Return to text

15. “Ma anzitutto la contiguità dei blocchi produce salti immensi d’ambiente: è una ricchezza d’informazione persino traumatica, nel brusco passaggio da un mondo sonoro all’altro. Inoltre, i blocchi imparentati e non contigui si collegano nella memoria, creano attraverso l’intermittenza una polifonia di relazioni

Return to text

16. “di un titolo figurativo, a dispetto di chi pretende che la musica non sia descrittiva, o di chi, al contrario, vorrebbe descritte in musica solo le proprie fantasticherie, proprio quelle che in apparenza rendono tranquilli i rapporti fra se stessi e il mondo. Un titolo ha sempre un legame stretis—” (“of a figurative title, in spite of those who claim that music is not descriptive, or of those who, on the contrary, would like to describe in music only their own fantasies, precisely those who apparently make the relations between themselves and the world peaceful. A title always has a strong bond—”)

Return to text

17. These durations refer to the recording Sciarrino 2008 (recorded in 2005).

Return to text

18. Of course, this again implies a certain amount of irony, given that the implicit (possibly “disinterested”) listener switches off the “radio” somewhat prematurely during the announcement of the work’s title.

Return to text

19. “Klagelied kaum je gestillter Sehnsucht.”

Return to text

20. In the available live recording (Sciarrino 2006), scene 30 begins at 42:10, i.e., after about 39% of the total duration (107:44).

Return to text

21. “A story without a story, devoid of shocking events as, in a close perspective, it is the daily life of each of us. A false stillness, woven of indecision, subterfuge, sadness, and the instability of those who do not know where to hide. Leaving the house together becomes a traumatic event; changing abode becomes an epochal outcome and the beginning, perhaps, of a new uncertainty. We look forward to conflicts that seem on the verge of coming.” (Sciarrino 2006, “Una storia senza storia, priva di avvenimenti sconvolgenti come, in una prospettiva ravvicinata, è il quotidiano di ciascuno di noi. Una falsa quiete, tessuta di indecisione, sotterfugi, tristezza, e dell’instabilità di chi non sa dove nascondersi. Uscire di casa insieme diviene un evento traumatico; cambiare dimora diviene un esito epocale e l’inizio, forse, di una nuova incertezza. Restiamo in attesa di conflitti che sembrano sul punto di giungere.”)

Return to text

Copyright Statement

Copyright © 2023 by the Society for Music Theory. All rights reserved.

[1] Copyrights for individual items published in Music Theory Online (MTO) are held by their authors. Items appearing in MTO may be saved and stored in electronic or paper form, and may be shared among individuals for purposes of scholarly research or discussion, but may not be republished in any form, electronic or print, without prior, written permission from the author(s), and advance notification of the editors of MTO.

[2] Any redistributed form of items published in MTO must include the following information in a form appropriate to the medium in which the items are to appear:

This item appeared in Music Theory Online in [VOLUME #, ISSUE #] on [DAY/MONTH/YEAR]. It was authored by [FULL NAME, EMAIL ADDRESS], with whose written permission it is reprinted here.

[3] Libraries may archive issues of MTO in electronic or paper form for public access so long as each issue is stored in its entirety, and no access fee is charged. Exceptions to these requirements must be approved in writing by the editors of MTO, who will act in accordance with the decisions of the Society for Music Theory.

This document and all portions thereof are protected by U.S. and international copyright laws. Material contained herein may be copied and/or distributed for research purposes only.

Prepared by Andrew Eason, Editorial Assistant

Number of visits:

5719