Response to Trevor de Clercq’s “Some Proposed Enhancements to the Operationalization of Prominence: Commentary on Michèle Duguay’s ‘Analyzing Vocal Placement in Recorded Virtual Space’”

Michèle Duguay

KEYWORDS: Virtual Space, Voice, Prominence, Popular Music, Gender

DOI: 10.30535/mto.30.1.3

Copyright © 2024 Society for Music Theory

[1] My 2022 article, “Analyzing Vocal Placement in Recorded Space,” outlines five parameters that affect the positioning of a voice within a virtual space: width, environment, layering, pitch, and prominence. In it, I propose that analysts use the following method to determine the prominence of a vocal track:

- Calculate the average of RMS (Root Mean Square) amplitude values in the isolated vocal track, omitting values under 0.02 to remove moments of silence or near-silence in the vocal track.

- Calculate the average of RMS amplitude values in the full mix.

- Express the prominence of the vocals as a percentage with the following formula:

[2] In his response, Trevor de Clercq proposes an alternate approach for calculating prominence:

- Determine the integrated LUFS (Loudness Units relative to Full Scale) of the isolated vocal track.

- Generate a track of the full mix minus the vocals (i.e., an instrumental track) by reversing the polarity of the isolated vocal track and mixing it with the full track.(1)

- Determine the integrated LUFS of the instrumental track.

- Express the prominence of the vocals in Loudness Units (LU) with the following formula:

[3] de Clercq’s approach departs from mine in two ways. First, de Clercq quantifies prominence with LUFS because it better captures the perceptual experience of loudness than average RMS Amplitude. Second, his methodology relies on different types of tracks than mine to determine prominence. My approach compares the isolated vocal track to the full mix and expresses the prominence of the vocals as a percentage. The resulting value represents the proportion of the full track’s average RMS Amplitude that is occupied by the vocals. de Clercq’s compares the isolated vocal track with an instrumental track that contains no vocals and expresses the prominence of the vocals in LU. The resulting value represents the difference between the loudness of the vocals and the loudness of the rest of the mix. It is important to note that de Clercq’s suggested method slightly shifts the original definition of prominence by measuring the extent to which the vocals are louder or softer than the other combined remaining sound sources in the mix. His method also implicitly suggests that the x axis be graduated according to LU in visual representations of the virtual space.

[4] There are several advantages to de Clercq’s approach. His solution is more elegant, as he explains, in that it requires less manual computation than my method. Instead of manipulating a high amount of datapoints to calculate the average RMS amplitude of two tracks, an analyst simply needs to subtract two LUFS values. His workflow adheres to the intent of my methodology by relying on user-friendly tools that do not require extensive training in audio feature analysis.(2) As de Clercq writes in paragraph 4.14, moreover, his method can be used to measure the prominence of other sound sources in a recording. This approach to prominence therefore enables more detailed ventures into the study of virtual space, potentially generating visual representations that encapsulate the placement of all sound sources in a mix.

[5] I will start by saying that I wholeheartedly welcome de Clercq’s attention to the perceptual experience of prominence. I agree that his approach provides a straightforward and intuitive means of quantifying the relative loudness of a voice against the rest of the mix. His contribution also carries the potential to inform further research into the perceptual components of virtual space. I can envision, for instance, an experiment assessing the extent to which listeners perceive minute differences in vocal prominence. Other studies could explore how one’s listening environment and audio equipment impact the perception of prominence and of the other parameters that constitute the virtual space. Such studies could be instrumental in the development of analytical tools that model the way listeners experience popular music.

[6] My response focuses on two points of discussion raised in de Clercq’s commentary. First, I contextualize his claims about the replicability of my method. de Clercq was unable to replicate my results because we used different isolated vocal tracks. For the same reason, I was also unable to replicate his prominence measurements. Ultimately, I show that these discrepancies are not caused by methodological flaws or by calculation errors, but rather by the imperfect state of source separation technologies. Second, I elaborate on the relationship between gender and vocal placement. de Clercq misrepresents my original argument by stating that I attribute differences in vocal placement to gender. The 2022 article made the opposite claim, stating that vocal placement contributes to the formation of a gendered soundscape in musical collaborations. I situate this approach within recent work on the topic, with the goal of generating further discussion on the relationship between gender and spatialization in recorded popular music.

Replicability of Prominence Measurements

[7] In paragraphs [2.11–2.13] of his response, de Clercq explains that he encountered some difficulties in replicating the prominence measurements provided in my article. The right column of his Example 2 shows the prominence values I originally calculated, while the column directly to its left displays the results that de Clercq obtained using my method. In eight out of nine cases, our prominence values differ by 6% or less. Rihanna’s first verse in “Love The Way You Lie (Part II)” is the sole exception. I calculated a prominence level of 92%, while de Clercq obtained a 74%.

[8] Given that we worked with the same methodology, he surmises that the discrepancies between our results may be due to variations in our workflow. We may have had mismatched time stamps or used different versions of software.(3) He also proposes that a miscalculation on my end might be at the root of our mismatched results. “Ultimately,” he writes, “it seems that the calculation of vocal prominence following the workflow outlined by Duguay may vary from user to user” [2.13]. His methodology is intended to provide a more consistent alternative to the measurement of prominence.

[9] I would emphasize that the discrepancies between our results are not caused by a miscalculation nor by an issue with the original method. Rather, they arose because de Clercq and I were working from different audio files. de Clercq attempted to replicate my results with isolated vocal tracks generated by Open-Unmix, but my analysis relied on tracks created with iZotope RX7’s Music Rebalance (Duguay 2022, [3.8]). Since isolated vocal tracks produced by different software vary from one another, it is natural that our results would differ. My article show two isolated vocal tracks (Audio Examples 4 and 5 in the original article) generated from the same recording to illustrate the extent to which different software can generate dissimilar results. In Audio Example 4, which was created with iZotope RX7, non-vocal sound sources bleed into the separated vocal track. In Audio Example 5, which was created with Open-Unmix, the isolated track does not capture all the reverberated images of a voice. The source separation model instead categorizes these vocal components as instrumental parts. In the verse of “Love the Way You Lie (Part II),” Rihanna’s voice is set in a highly reverberant environment. It is likely that our different software simply categorized some of the reverberated images differently, therefore creating more variation in our prominence results.

Example 1

(click to enlarge)

Audio Example 1

Audio Example 2

Audio Example 3

Audio Example 4

Audio Example 5

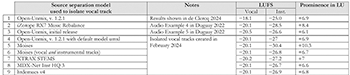

[10] It is true that de Clercq’s methodology requires only one calculation, which presents fewer opportunities for error. Importantly, this feature does not automatically guarantee replicable results between users who are working from different isolated vocal tracks. Using de Clercq’s method, I measured the prominence in LU of Rihanna’s vocals in the first chorus of “Love the Way You Lie.” With the aid of seven source separation models, I created different isolated vocal tracks of the same excerpt. The results are displayed in Example 1.(4) Row 1 reproduces de Clercq’s results as reported in his Example 8. Rows 2 and 3 measure the prominence of the two isolated vocal tracks included in my original article. The remaining rows use vocal tracks obtained with the following models:

- Open-Unmix 1.2.1’s default source separation model, umxl (Audio Example 1).

- Moises, version 1.0.49, “2 tracks” option (Audio Example 2). I measured the prominence of this vocal track twice by comparing it to 1) an instrumental track also created by Moises, and to 2) an instrumental track obtained through polarity reversal.

- Audionamix’s source separation application XTRAX STEMS, “4 Stems” option (Audio Example 3).

- MDX-Net Inst HQ3 (Audio Example 4)(5)

- htdemucs v4 (Rouard, Massa, and Défossez 2023) (Audio Example 5)(6)

[11] As Example 1 shows, de Clercq’s methodology yields varying results when applied to different isolated vocal tracks. Although I was able to replicate de Clercq’s results by using a vocal track created by the most recent version of Open-Unmix (rows 1 and 4), the prominence values I obtained for other tracks, while roughly similar, all differ from one another. The lack of replicability observed in both of our methodologies is indicative of a broader issue in the analysis of vocal placement: the imperfect state of source separation technologies. Until models yield consistent, nearly identical results, analysts will be unable to obtain matching prominence results even if they use the same methodology. Fortunately, source separation software is evolving quickly and producing increasingly accurate isolated vocal tracks. For example, when I isolated the vocal tracks for my article, the 2019 initial release of Open-Unmix (which then offered state-of-the-art technology in source separation) still yielded imperfect results. When preparing this response, I was pleased to observe that the newly created isolated files were much more accurate than the ones presented in my article.(7) We may soon reach a point where analysts can provide precise and accurate measurements of prominence with minimal variability from one isolated track to the next.(8)

Example 2

(click to enlarge)

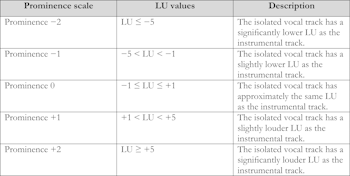

[12] In the interests of advancing this discussion toward further productive ends, I would suggest two potential solutions for ensuring more replicable prominence measurements. The first is to have analysts make their isolated vocal tracks publicly available to ensure replicability. The second is to work to acculturate analysts to expect and account for a reasonable level of variation from one analysis to the other. While the LU values in Example 1 exhibit variability, for instance, they all invite the same observation: Rihanna’s vocals in the first chorus of “Love the Way You Lie” are more prominent, by at least 6 LUs, than the instrumental track that accompanies her. To account for the variations in LUFS that arise when analyzing different isolated or instrumental tracks, analysts could rely on a generally agreed-upon system such as the five-point scale suggested in Example 2. According to this scale, for instance, all LU values in Example 1 belong to the “Prominence +2” category. The scale assumes that different isolated vocal tracks, while not identical, are similar enough to provide meaningful prominence results.(9) In this sketch of a model, the thresholds between categories remain arbitrary. Obviously, much further work would be needed to determine stricter scale criteria to allow the model to better align with the perceptual experience of prominence.

Vocal Placement and Gender

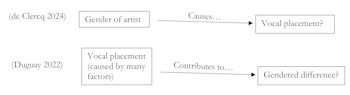

[13] My second area of concern relates to de Clercq’s representation of my argument on the potential relationship between vocal placement and gender. My 2022 article demonstrates how Rihanna’s and Eminem’s recorded voices are starkly differentiated across their four collaborations: Rihanna’s voice tends to be positioned in a more reverberated, layered, and wide space than Eminem’s voice. As a result, his vocals sound relatively centered and stable in comparison with Rihanna’s more diffuse, mobile vocal placement. I suggest that “these contrasting vocal placements perhaps contribute to the sonic construction of a gender binary, exemplifying one of the ways in which dichotomous conceptions of gender are reinforced through the sound of popular music [4.10].” In his response, de Clercq writes that “it is unclear . . . to what extent the differences in vocal prominence that Duguay identifies can be attributed to gender (as she suggests in [1.7] and [4.10]) as opposed to other factors [5.3].” He explains that other elements, such as musical form, may be the cause of variations in vocal placement.

[14] This summary misrepresents my argument: I do not suggest a causal relationship in which the gender of the artists directly impacts the way they are spatialized in a recording. I agree that many factors influence mixing practices in commercial popular music; these include genre, musical micro-trends, artists’ or producers’ preferences, personnel, vocal range and tessitura, formal conventions resulting in texturally dense choruses and thin verses, and many others. It would be misguided, in my opinion, to try and identify the “cause” of vocal placements without a detailed ethnography of mixing practices.

Example 3

(click to enlarge)

[15] Rather than claiming that differences in vocal spatialization are caused by gender, I make somewhat of the opposite argument. I suggest that vocal placement “contributes to the sonic formation of gendered difference [1.7],” and that “contrasting vocal placements. . . [exemplify] one of the ways in which dichotomous conceptions of gender are reinforced through the sound of popular music [4.10].” Gender, in other words, is not the cause of vocal placement. It is one of its results. The difference between both claims is schematically summarized in Example 3. My approach is in dialogue with recent work that explores the formative role of sound in constructing identity (Eidsheim 2019, Obadike 2005, Provenzano 2019, Reddington 2018, to only name a few.) As I have proposed elsewhere (2021), we can consider the sound of commercially successful popular music as a gendered soundscape (Järviluoma, Moisala, and Vilkko 2003, 99) that defines, reifies, and contests received notions of gender. As Christine Ehrick writes, “Although many of us have been well-trained to look for gender, I consider what it means to listen for it.” Listening for gender in this way, she argues, can shift our attention to “the ways that power, inequality and agency might be expressed in the sonic realm” (2015).

[16] In the context of popular music, I am especially interested in the politics of gendered soundscapes in musical collaborations, where the case of Rihanna and Eminem proves to be an illustrative example. In every instance that the two artists appear on a track together, they assume a vocal placement configuration that generally presents Rihanna’s voice as ornamental and diffuse and Eminem’s voice as direct and relatable. This differentiation could perhaps be attributed, as de Clercq suggests, to formal conventions, since Rihanna sings all the choruses. Mixing practices for different ranges and vocal delivery styles might also be at play.

[17] The sung vocal hook/rapped verse(s) structure encountered in Rihanna’s and Eminem’s collaborations, however, is extremely common in commercial popular music collaborations. To examine this phenomenon, I previously assembled a corpus containing the 113 songs that featured at least one man and at least one woman on the 2008–18 Billboard Year-end “Hot 100.” Within the corpus, the most common type of collaboration features men rapping and women singing (45 songs). The reverse configuration, in which a woman raps and a man sings, is much rarer (5 songs). Through an analysis of vocal placement, I concluded that, throughout the corpus, In the soundscape of the corpus—and of chart-topping collaborations between 2008–18—one is more likely hear a collaboration between a man and a woman that is spatialized along the same lines as Rihanna and Eminem. Within this collaboration, the woman is much more likely to perform a repeated chorus, while men advance the narrative through verses. The opposite configuration, heard, for instance, in Justin Bieber’s 2012 hit “Beauty and a Beat,” ft. Nicki Minaj, is far less common.

[18] Kate Mancey, Johanna Devaney, and I have recently expanded on this work by assembling and analyzing the Collaborative Song Dataset (CoSoD) (2023). CoSoD is a 331-song dataset of all multi-artist collaborations on the 2010–2019 Billboard “Hot 100” year-end charts. The dataset includes Billboard rankings, year, title, collaboration type, gender of artists, and other relevant metadata for each track. We also created analytical files that contain, among other features, vocal placement data on Layering, Environment, and Width. In the same paper, we present an experiment examining the relationship between the gender of a performer and their vocal placement.(10) Our analysis of a subset of the corpus (574 verses and choruses) reveals a statistically significant difference between the ways in which men’s and women’s voices are treated in terms of Width and Environment. Women’s voices are more likely to be set in reverberant environments and occupy a wider space than men’s voices, echoing the trend found in Rihanna’s and Eminem’s collaborations.

[19] The studies described above do not pinpoint the causation of different vocal placements. They instead underscore how multiple factors coalesce to sonically differentiate men’s and women’s voices in the popular music soundscape. My goal is to identify these trends and interrogate their broader cultural implications. How, when, and why did musical collaborations settle into this sonic and formal trope? What kinds of gendered stereotypes are reproduced when voices are spatialized according to certain conventions? How is the gender binary reinforced through these aesthetic practices? Could we imagine an alternate 2010s pop soundscape filled with collaborations in which men sing hooks while women rap verses? What might such a gendered soundscape imply? How have certain artists pushed back, been subsumed into, or reinvented gendered sonic trends? By presenting detailed data on vocal placement, CoSoD also allows for further inquiry into these questions. It also opens the way for further experiment on the way form, vocal delivery style, year of release correlate with gender, vocal placement, and other musical features. One could for instance set up a counter-study that observes vocal placement in collaborations where two men collaborate.

[20] The current version of CoSoD does not provide data on prominence. We opted to withhold this measurement at this stage, given the imperfect state of source separation technology. Thanks to recent improvements in source separation technology and to de Clercq’s more perceptually-relevant workflow, this data could now potentially be added. For this reason, I am grateful for de Clercq’s modification to my methodology. I anticipate that it will be instrumental to analysts as they continue to study gendered soundscapes and spatialization conventions in recorded popular music.

Michèle Duguay

Harvard University

3 Oxford Street, 305N

Cambridge, MA 02138

mduguay@fas.harvard.edu

Works Cited

Anjok07. 2023. “ultimatevocalremovergui.” GitHub Repository. https://github.com/Anjok07/ultimatevocalremovergui.

Duguay, Michèle. 2021. “Gendering the Virtual Space: Sonic Femininities and Masculinities in Contemporary Top 40 Music.” PhD diss., The Graduate Center, CUNY.

—————. 2022. “Analyzing Vocal Placement in Recorded Virtual Space,” Music Theory Online 28 no. 4. https://mtosmt.org/issues/mto.22.28.4/mto.22.28.4.duguay.html

Duguay, Michèle, Johanna Devaney, and Kate Mancey. 2023. “Collaborative Song Dataset (CoSoD): An Annotated Dataset of Multi-Artist Collaborations in Popular Music.” In Proceedings of the 24th International Society for Music Information Retrieval Conference (ISMIR), Milan, Italy, Nov. 5–9.

Ehrick, Christine. 2015. “Vocal Gender and the Gendered Soundscape: At the Intersection of Gender Studies and Sound Studies.” Sounding Out! Blog, February 2. https://soundstudiesblog.com/2015/02/02/vocal-gender-and-the-gendered-soundscape-at-the-intersection-of-gender-studies-and-sound-studies/.

Eidsheim, Nina Sun. 2019. The Race of Sound: Listening, Timbre, and Vocality in African American Music. Durham: Duke University Press.

Fabbro, Giorgio, Stefan Uhlich, Chieh-Hsin Lai, Woosung Choi, Marco Martínez-Ramírez, Weihsiang Liao, Igor Gadelha, et al. 2024.“The Sound Demixing Challenge 2023 – Music Demixing Track.” arXiv, 2024. http://arxiv.org/abs/2308.06979.

Jäviluoma, Helmi, Pirkko Moisala, and Anni Vilkko. 2003. Gender and Qualitative Methods. SAGE Publications.

Morrison, Matthew D. 2019. “Race, Blacksound, and the (Re)Making of Musicological Discourse.&rdquo Journal of the American Musicological Society 72 (3): 781–823. https://doi.org/10.1525/jams.2019.72.3.781.

Obadike, Mendi Dessalines Shirley Lewis Townsend. 2005. “Low Fidelity: Stereotyped Blackness in the Field of Sound.” Ph.D. diss., Duke University.

Provenzano, Catherine. 2019. “Making Voices: The Gendering of Pitch Correction and the Auto Tune Effect in Contemporary Pop Music.” Journal of Popular Music Studies 31 (2): 63–84.

Reddington, Helen. 2018. “Gender Ventriloquism in Studio Production.” IASPM Journal 8 (1): 59–73.

Rouard, Simon, Francisco Massa, and Alexandre Défossez. 2023. “Hybrid Transformers for Music Source Separation.” IC 2023 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech, and Signal Processing (ICASSP 2023), Rhodes, Greece, June 4–10. https://arxiv.org/abs/2211.08553.

Footnotes

1. The polarity of a track can be reversed in Audacity with Effect > Invert.

Return to text

2. de Clercq recommends the Youlean Loudness Meter, which—despite being available in a free version—requires the Pro version (priced at 39.99 USD as of this writing) to calculate the integrated LUFS of an audio file. The free audio editing software Audacity, already familiar to many music analysts, can be used to generate the instrumental mix.

Return to text

3. De Clercq and I used v4 of Jamie Bullock’s LibXtract Library to determine the RMS Amplitude of audio files. We used different versions of the Open-Unmix software to isolate vocal tracks. De Clercq used Open-Unmix 1.2.1, which was made available on July 23, 2021. I used the initial release of Open-Unmix, which was available in throughout 2020, to isolate the vocal tracks analyzed in my 2022 article.

Return to text

4. Unless indicated otherwise, all instrumental tracks were generated on Audacity through polarity reversal.

Return to text

5. This source separation model was trained by the developers of Ultimate Vocal Remover Anjok07 2023.

Return to text

6. I used Version 5.6 of Ultimate Vocal Remover GUI.

Return to text

7. I have not tested more recent versions of iZotope’s Music Rebalance tool.

Return to text

8. Researchers in academia and industry frequently release updates and new versions of existing models. For an overview of recent developments in source separation models as they apply to music, see Fabbro et al. (2023).

Return to text

9. Since LU are a continuous data, a sliding scale would offer the best solution.

Return to text

10. As explained in the article, we opted not to consider the artists’ race in this study to account for the dynamics of Blacksound, as formulated by Matthew D. Morrison (2019). More work is necessary to understand how to best address these issues in datasets, corpus studies, and other large-scale music analytical projects.

Return to text

Copyright Statement

Copyright © 2024 by the Society for Music Theory. All rights reserved.

[1] Copyrights for individual items published in Music Theory Online (MTO) are held by their authors. Items appearing in MTO may be saved and stored in electronic or paper form, and may be shared among individuals for purposes of scholarly research or discussion, but may not be republished in any form, electronic or print, without prior, written permission from the author(s), and advance notification of the editors of MTO.

[2] Any redistributed form of items published in MTO must include the following information in a form appropriate to the medium in which the items are to appear:

This item appeared in Music Theory Online in [VOLUME #, ISSUE #] on [DAY/MONTH/YEAR]. It was authored by [FULL NAME, EMAIL ADDRESS], with whose written permission it is reprinted here.

[3] Libraries may archive issues of MTO in electronic or paper form for public access so long as each issue is stored in its entirety, and no access fee is charged. Exceptions to these requirements must be approved in writing by the editors of MTO, who will act in accordance with the decisions of the Society for Music Theory.

This document and all portions thereof are protected by U.S. and international copyright laws. Material contained herein may be copied and/or distributed for research purposes only.

Prepared by Andrew Blake, Editorial Assistant

Number of visits:

3057