Review of Violetta Kostka, Paulo F. de Castro, and William A. Everett, eds., Intertextuality in Music: Dialogic Composition (Routledge, 2021)

Cristina González Rojo

DOI: 10.30535/mto.30.1.10

Copyright © 2024 Society for Music Theory

[1] Intertextuality in Music: Dialogic Composition, published in 2021 by Routledge, is a collection of essays edited by Violetta Kostka, Paulo F. de Castro, and William A. Everett. The main purpose of the volume is to reexamine existing theoretical approaches to intertextuality(1) and to propose a renewed dialogue with “traditional and less traditional subdisciplines of musicology, such as history, analysis, aesthetics, hermeneutics and performance studies” (6). The editorial goals are met on both counts, first, as several authors reflect on the methodological ins and outs of extant intertextual approaches and their use in musical analysis, such as those of Julia Kristeva (Chapters 1, and 3), Gérard Genette (Chapters 8–11), and Michael Riffaterre and Ryszard Nycz (Chapter 5), and second, as the aforementioned subdisciplines of musicology are explored through a wide range of repertoires and genres. Intertextuality in Music’s focus on twentieth- and twenty-first-century works, as well as its inclusion of various chapters on musical theater, makes it a noteworthy contribution to the field.

[2] Since the 1980s, theories of intertextuality have been increasingly applied to music. The topic of musical borrowing—the use of preexisting music in another work—initiated this trend, with near simultaneous contributions from Vladimír Karbusický (1983)(2) and J. Peter Burkholder (1983).(3) While at first the focus was on musical borrowing, the network of connections soon expanded, with scholars studying the links between a musical piece and earlier styles of composition referenced in it. Robert Hatten’s 1985 article, “The Place of Intertextuality in Music Studies,” pioneered this broader conception of intertextuality. To cite one example, Hatten (1985, 71) explains that the polyphonic vocal style of the High Renaissance became the stile antico of the Baroque and that it retained serious and solemn connotations for Baroque listeners when they encountered a reference to it in the music of their time. The study of intertextuality then continued to grow: the 1990s saw seminal works by Joseph Straus (1990) and Kevin Korsyn (1991), while Michael L. Klein published his influential study Intertextuality in Western Art Music in 2005. Since that time, several scholars from different musical fields have published monographs and essay collections, particularly in popular music studies, notably The Pop Palimpsest (2018) by Lori Burns and Serge Lacasse.

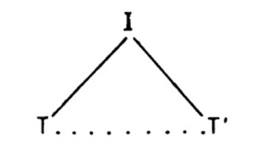

Example 1. Interpretant (I), intertext (T), and text (T’) in a semiotic triangle by Riffaterre (Krawczyk 2020, 263)

(click to enlarge)

[3] Even as the field of intertextuality is well established and now flourishing, there are still unresolved issues that this volume seeks to address. The first one concerns methodological consensus. Two different models have been adapted from literary theory and are currently being used for music analysis; one is from Michael Riffaterre (1979) and the other is from Gérard Genette (1982). Riffaterre defines the concept of intertext as a set of texts that arises in the memory of a recipient while reading. This reading process is understood as a Peircean semiotic triangle formed by the text read, the intertext, and the interpretant (see Example 1). According to this model, the whole act of intertextual reading depends on the interpretant, which functions as a third mediating text (Krawczyk 2020, 263). While Riffaterre’s system has “clear pragmatic and hermeneutic assumptions” (Castro, Kostka, and Everrett 2021, 3), Genette’s “quasi-structuralist” model establishes a five-part categorization of “transtextual relations.”(4) While the editors do not promote one approach over the other, Riffaterre’s method, with its hermeneutic trend, is dealt with extensively within the volume.

[4] A further methodological challenge facing scholars in this field is its increasing tendency towards isolation. In the last twenty years, most of the publications dealing with intertextuality concentrates on specific repertoires, such as jazz (Monson 1996, 97–132), Western art music (Klein 2005), Stephen Sondheim’s musicals (Gordon 2014), and popular music (Burns and Lacasse 2018). Alongside discussions on methodology, there are some terminological disagreements that this volume seeks to address. While some authors limit intertextuality to direct quotations and allusions, others use it in a broader sense, referring to all kinds of transtextual relations, as, for example, in the title of this volume.

[5] Intertextuality in Music in many ways represents a communal response to several longstanding issues in the field. And rather than present one large, self-contained publication, this work brings different repertoires together, with a focus on twentieth and twenty-first-century academic music. In the process, the volume broadens the traditional concept of intertextuality, previously limited to quotations and allusions, to include other features, such as topical references. As this occurs, the book’s various contributors provide the bases through which a wide array of analyses can benefit from intertextual tools.

[6] Intertextuality in Music is structured in four parts, each composed of essays that both stand alone and work in dialogue with each other. The first part, which lays the theoretical framework and seeks to provide refreshing ideas for musicology in a broader sense, is composed of four chapters written by internationally renowned scholars in the field: Lawrence Kramer, Nicholas Cook, Michael L. Klein, and J. Peter Burkholder. Kramer (Chapter 1) presents his view of heterogeneity as definitive of the entire experience of communication, representation, and expression. Cook (Chapter 2) proposes a new contemporary conception of the classical tradition, with creative insights on intertextual connections in serial music. As Cook argues, a detachment can be observed between the intellectual discourse on music and the listening and performative practices. The “ideology of musical autonomy” (48–49), in his words, is one example of how an overstated conception of autonomy dominating culture in the nineteenth century has had an influence on postmodern ways of listening. Nonetheless, Cook reflects on how some of the premodern ways of listening—such as mimetic listening—continue to exist today in film and opera.

[7] Klein (Chapter 3) reflects on two conceptions of intertextuality, one that involves searching for allusions and quotations and another that involves studying the text’s typology (the types of writing it includes) and the social/historical context within which the text operates. The search for musical topoi within a given musical work can itself be studied as an intertextual practice. Burkholder (Chapter 4) presents intertextuality as one method that allows us to make new music out of old, together with other practices such as performance, arranging, borrowing, schemata, and topoi.

[8] The second part of Intertextuality in Music is given over to providing further analysis and practical examples. It includes intertextual analyses of works by two Polish contemporary composers, Pawel Szymański and Dariusz Przybylski, as well as of the British contemporary composers Peter Maxwell Davies and Harrison Birtwistle. Violetta Kostka (Chapter 5), relying on Ryszard Nycz’s theory of intertextual poetics, describes intertextuality in Szymański’s work as “structural in nature” (93), running from the beginning to the end of his œuvre. Katarzina Szymańska-Stulka (Chapter 6) starts by applying Barbara Skarga’s concepts of “trace and presence” to her intertextual analysis of Przybylski’s Schübler Choräle for organ, Op. 48; from there, she reflects on how the presence of musical motives from earlier periods in the works—such as traces of the Lutheran hymn “Wachet auf, ruft uns die Stimme”—invites listeners to engage in intertextual dialogue, defying historical frameworks. Alexander Kolassa (Chapter 7) studies the role of modernist Medievalism in Britain, specifically in Birtwistle’s and Davies’s music, and proposes an intertextual study that brings new understandings to modernism and its presumed idea of linear temporalities and progress.

[9] The third part of the book, which is dedicated to Genette’s transtextuality model, includes chapters by Paulo F. de Castro (Chapter 8), William A. Everett (Chapter 9), and Nils Grosch (Chapter 10). De Castro’s chapter adapts Genette’s literary theory for musical analysis, including musical examples from different styles and periods for each of Genette’s five categories. Everett and Grosch’s chapters focus on musical theater and its role as a place for transtextuality. Everett’s chapter starts by reflecting on the role of intertextuality as a means for engaging audiences in the theater. The Geisha, premiered in 1896, works as a hypotext in several media, such as literature and opera. Everett suggests that it might have influenced Puccini’s Madama Butterfly (1904) and left an imprint in Joyce’s Ulysses. Critically, he does not limit his claims to hypotextuality alone; he continues by arguing that The Geisha’s variety of transtextual relationships (hypertextuality, architextuality, and paratextuality) make it a worthwhile case study. Grosch’s chapter, which similarly applies Genette’s theory but in a novel way, deals with pastiche as a fundamental technique for the construction of the musical dramaturgy in the theater.

[10] The final part of Intertextuality in Music seeks to further expand past approaches to the question of musical meaning. In keeping with this goal, it scrutinizes a diverse array of music using four different intertextual approaches. Tijana Popović Mladjenović and Leon Stefanija (Chapter 11) propose the idea of a “polyphonic trace of otherness” (171) as a metaphor for the web of indexical and symbolic allusions coexisting in a musical work. In a similar fashion, the chapter by Mark Hutchinson (Chapter 12) that immediately succeeds theirs offers an analysis of Stele (ΣΤΉΛΗ), Op. 33 by György Kurtág and explores “the varied ways in which text of every kind (literary, poetic, philosophical, musical) can create connections across history” (199). Francesca Placanica and Edward Venn offer separate intertextual analyses: Placanica’s entry concentrates on Luciano Berio’s Recital I (for Cathy), taking into account its performance as an additional layer of intertextuality, while Venn’s examines Thomas Adés’s Powder Her Face, untangling several allusions and borrowings that affect its message.

[11] The stated goal of Intertextuality in Music is to put in dialogue the different existing theoretical approaches to intertextuality in music. The volume, rather than promoting one method as paradigmatic, aims to show useful analytical applications of existing approaches. (The four sections of the book, which engage in myriad cross-references among sections and chapters, fortuitously exhibits an intertextual practice that gives textual and aesthetic cohesion to the whole.) As to the question of whether one or more models will eventually prevail, this volume does not offer a firm answer. Perhaps because of the developing status of this discipline, rather than privileging one method over the other, the book pursues a simpler—but no less necessary—goal of proposing a renewed, multivoiced, and relational dialogue between methodologies.

[12] Further supplementing Klein’s (2005) landmark volume, which extended only to Witold Lutosławski, the present volume covers even more recent composers, such as Thomas Adès and Pawel Szymański. The intertextual analysis of this more recent repertoire provides at least two benefits. First, it proposes new ways of hearing these works and connects the readership with the music of our time. Second, studying intertextuality in contemporary music entails covering the earlier composers and styles with which contemporary works form intertexts. Also, in regards to the editors’ intended diversity of thematic scope, it was certainly a fitting move to include two chapters in this section that analyze musical theater, since in that genre, intertextuality stands out as a powerful tool for constructing meaning and engaging with contemporary audiences. Already in 2014, The Oxford Handbook of Sondheim Studies included five chapters on the topic of intertextuality and authorship. In a fruitful exchange, this volume gives back with its own set of methodologies for the analysis of musical theater, offering valuable insights in terms of audience-author dynamics and the role of intertextuality in constructing up-to-date meanings.

[13] In contrast to the specificity of other collective volumes on intertextuality, both in terms of methodologies and repertoires, the authors of this collection have put together a heterogenous artifact, inviting perspectives from different positionalities and academic traditions. A further strength of the volume is that it explicitly incorporates subdisciplines that have contributed to the understanding of intertextuality, even under other names. This is the case, for example, with topic theory, which is recognized as intertextual by several chapters in this volume. Already in 1986, Wye Jamison Allanbrook analyzed Mozart’s operas as intertexts, arguing that the musical topics featured in Mozart’s operas constituted an expressive vocabulary that was well known to their listeners and that provided relevant input beyond plot to the audience. Following Allanbrook, Kofi Agawu in Playing with Signs (1991) remarked on the intertextual character of musical discourse, in which referentiality plays a major role pointing to the expressive meanings of the work. Finally, after several decades of cursory treatment of intertextuality in topic theory analyses, this volume offers substantial theoretical reflections on the relationship between intertextuality and topic theory. Building on Genette’s model, de Castro explains topic theory as “architextual,” one of Genette’s five categories that includes “those overarching categories shaping the reader’s expectations: canons, genres, types and topics of discourse” (134). Klein (Chapter 3) also identifies topics as a type of intertextuality, building on Julia Kristeva’s theory, concluding that topical gestures derive their denotative power from their functional origin. A genealogical study of topics, Klein argues, tends to reveal a background in some kind of functional music, such as military, ball room, sacred, and theatre music, as well as lyrical poetry. All of these topical fields, with their associated meanings, interact within a musical piece in an intertextual manner.

[14] Intertextuality in Music emerges at a time when musicology embraces heterogeneity as a virtue, leaving behind the idea of the autonomous musical work and incorporating listener-centered approaches. The volume’s contributions are extremely timely, as theories of intertextuality encompass the study of musical signification, including topic theory, studies on rhetoric, temporalities, and narrativity, among others. The book thus provides its field with a more robust methodological scaffold. This volume also recognizes that several contexts interact with a musical work, and thus reconciles the historical-genealogical and sociocultural approaches to musical meaning. The negotiation of meaning (the relationship between the musical text and its intertexts) is thus not merely arbitrary, nor is it scientifically objective: it is intersubjective, inscribed in a community of listeners that share meanings and cultural referents.

Cristina González Rojo

Columbia University

Department of Music

621 Dodge Hall

2960 Broadway

New York, NY 10027

c.gonzalezrojo@columbia.edu

Works Cited

Agawu, Victor Kofi. 1991. Playing with Signs: A Semiotic Interpretation of Classic Music. Princeton Legacy Library. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

Allanbrook, Wye Jamison. 1986. Rhythmic Gesture in Mozart: Le Nozze Di Figaro e Don Giovanni. The University of Chicago Press.

Burkholder, J. Peter. 1983. “The Evolution of Charles Ives’s Music: Aesthetics, Quotation, Technique.” PhD diss., The University of Chicago.

—————. 2013. “Intertextuality.” In Grove Music Online, ed. Deane Root. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.A2241764.

Burns, Lori, and Serge Lacasse, eds. 2018. The Pop Palimpsest: Intertextuality in Recorded Popular Music. University of Michigan Press. https://doi.org/10.3998/mpub.9755813.

Genette, Gérard. 1982. Palimpsestes. La Littérature au second degré. Seuil. Translated by Channa Newman and Claude Doubinsky 1997 as Palimpsests: Literature in the Second Degree. University of Nebraska Press.

Gordon, Robert, ed. 2014. The Oxford Handbook of Sondheim Studies. Vol. 1. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780195391374.001.0001.

Hatten, Robert S. 1985. “The Place of Intertextuality in Music Studies.” American Journal of Semiotics 3 (4): 69–82. https://doi.org/10.5840/ajs1985345.

Karbusický, Vladimír. 1983. “Intertextualität in der Musik.” In Dialog der Texte. Hamburger Kolloquium zur Intertextualität [Wiener Slawistischer Almanach, Sonderband 11], ed. Wolf Schmid and Wolf-Dieter Stempel, 361–98. Institut für Slawistik der Universität Wien.

Klein, Michael L. 2005. Intertextuality in Western Art Music. Indiana University Press.

Korsyn, Kevin. 1991. “Towards a New Poetics of Musical Influence.” Music Analysis 10 (1–2): 3–72. https://doi.org/10.2307/853998.

Krawczyk, Mateusz Andrzej. 2020. “Michael Riffaterre’s ‘Interpretant’ Reinterpreted.” The Biblical Annals 10 (2): 261–77. https://doi.org/10.31743/biban.5139.

Monson, Ingrid. 1996. Saying Something: Jazz Improvisation and Interaction. The University of Chicago Press. https://doi.org/10.7208/chicago/9780226534794.001.0001.

Riffaterre, Michael. 1979. La Production du texte. Seuil. Translated by Terese Lyons 1983 as Text Production. Columbia University Press.

Straus, Joseph N. 1990. Remaking the Past: Musical Modernism and the Influence of the Tonal Tradition. Harvard University Press. https://doi.org/10.4159/harvard.9780674436336.

Footnotes

1. Intertextuality in music addresses “the entire range of ways a musical work refers to or draws on other musical works” (Burkholder 2013).

Return to text

2. Karbusický presented a paper titled “Intertextualität in der Musik” in the Hamburger Kolloquium zur Intertextualität.

Return to text

3. Burkholder defended his dissertation on musical borrowing in the works of Charles Ives.

Return to text

4. Intertextuality (allusion, quotation, plagiarism . . .), paratextuality (title, subtitle, preface . . . ), metatextuality (commentary), hypertextuality (parody, travesty, pastiche), and architextuality (types of discourse, genres).

Return to text

Copyright Statement

Copyright © 2024 by the Society for Music Theory. All rights reserved.

[1] Copyrights for individual items published in Music Theory Online (MTO) are held by their authors. Items appearing in MTO may be saved and stored in electronic or paper form, and may be shared among individuals for purposes of scholarly research or discussion, but may not be republished in any form, electronic or print, without prior, written permission from the author(s), and advance notification of the editors of MTO.

[2] Any redistributed form of items published in MTO must include the following information in a form appropriate to the medium in which the items are to appear:

This item appeared in Music Theory Online in [VOLUME #, ISSUE #] on [DAY/MONTH/YEAR]. It was authored by [FULL NAME, EMAIL ADDRESS], with whose written permission it is reprinted here.

[3] Libraries may archive issues of MTO in electronic or paper form for public access so long as each issue is stored in its entirety, and no access fee is charged. Exceptions to these requirements must be approved in writing by the editors of MTO, who will act in accordance with the decisions of the Society for Music Theory.

This document and all portions thereof are protected by U.S. and international copyright laws. Material contained herein may be copied and/or distributed for research purposes only.

Prepared by Brent Yorgason, Managing Editor

Number of visits:

4689