Kaleidoscopic Topics in the Music of György Ligeti and Thomas Adès

James Donaldson

KEYWORDS: topic theory, isotopy, post-tonal music, semiotics, György Ligeti, Thomas Adès

ABSTRACT: This article applies the concept of isotopy to music to trace the dynamic appearances and interactions of topics in three works by György Ligeti and Thomas Adès. In contrast to previous applications of isotopy to music, the model I propose here is explicitly topic-centered, leading me to a complementary reconfiguring of Johanna Frymoyer’s hierarchy of topical characteristics. My theoretical adaptions are motivated by the observations that: (1) a topic’s identity is often unclear (Frymoyer 2017, Sánchez-Kisielewska 2023), an ambiguity which can be exploited compositionally; (2) the same topic can recur at different degrees of clarity in a single work, leading the listener to draw out a larger structural role for the topic (isotopy) in lieu of clear formal processes in other parameters in this repertoire (harmony, rhythm, etc.); and (3) if multiple topics are engaged, they can relate to one another in formally significant ways. Using the Chorale topic as a case study, I first demonstrate a simple closed isotopy in the second movement of Ligeti’s Violin Concerto, followed by open isotopies of the Chorale and Sound Mass topics in Ligeti’s Hamburg Concerto. Finally, in applying this approach to Thomas Adès’s Piano Quintet I demonstrate how an isotopic analysis can work in dialogue with the familiar trajectory of sonata form. This approach aims to draw out semantic aspects of Ligeti’s and Adès’s highly referential style, which is representative of late-twentieth century, semantically dense, post-collage compositions, filled with familiar topics shifting in and out of focus kaleidoscopically.

DOI: 10.30535/mto.30.2.2

Copyright © 2024 Society for Music Theory

Introduction

[1.1] In his influential 1979 text The Role of the Reader, Umberto Eco proposes the following scenario:

Mary is playing her cello. On the other hand, John is eating bananas. (Eco 1979, 25)

At first blush this passage appears nonsensical. While the phrase “on the other hand” suggests an opposition, the subjects (Mary and John), actions (playing and eating), and objects (cello and bananas) do not align as oppositions in any immediate way. Although Mary and John are separate individuals who can perhaps be contrasted, neither their actions of playing and eating nor the characteristics of bananas and cellos are poles on a semantic axis. Consequently, the scenario does not cohere and is effectively meaningless.

[1.2] What if, Eco asks, we prefaced these sentences with the following:

What the hell are those kids doing? They were supposed to have their music lessons! (Eco 1979, 25)

A clarity suddenly springs out, an “aha” moment of meaning with the concept of “music lessons” now framing John’s eating of bananas as antithetical to his lack of music practice which Mary, in contrast, is already doing. Only when the specific question is asked—and the words “music lessons” appear—is John’s lackadaisical behavior contextualized as an opposition to Mary’s diligent practice. Through the appearance of this new idea, the scenario coheres and the topic of “music lessons” links together otherwise disparate elements of the initial scenario, selecting the semantic properties that enable the reader to understand a narrative structure and create a meaningful whole.

[1.3] Compare Eco’s example to Kofi Agawu’s analysis of the opening of the first movement of Mozart’s Piano Concerto, K. 467:

these measures [mm. 1–4] assume clear topical identity only after one has heard the more explicit march in mm. 7–8. That is, by a process of retrospective deduction, the identity of mm. 7–8 is projected [retrospectively] onto that of mm. 1–4, since the former lack an explicit topical characterization when they are first heard. Their apparent neutrality is undermined as they are shown to be compatible with the march topic. (Agawu 1991, 35–36, italics mine.)

In mm. 1–4, the topic of the March is unclear as only the

[1.4] In literary theory, the term isotopy describes such a process of reading, in which the reader actively constructs narrative meaning by applying a topic to draw out a uniform interpretation of a text. Topic, in this literary context, is “an abductive schema that helps the reader to decide which semantic properties have to be actualized” (Eco 1979, 27). Though similar to musical topics, Eco’s literary topic is strongly rooted in the narrative dimension, such that, through identifying such a literary topic and its associated elements, isotopy coheres seemingly disparate material to uncover meaning. Eco’s example focuses on the sentence level, but similar abductive readings have been productively applied to larger scale narratives.(2)

[1.5] This article applies isotopy to music to trace the dynamic appearances and interactions of topics in two works of György Ligeti and one by Thomas Adès. The concept of isotopy has previously been applied to music; I adapt its principles to create a more explicitly topic-centered model. In the process, I modify Johanna Frymoyer’s (2017) hierarchy of topical characteristics, complementing her original version. I aim to draw out a property of the semantics of Ligeti’s and Adès’s highly referential style. The works I discuss below are representative of a late-twentieth century, semantically dense, post-collage compositional approach where recognizable topics shift in and out of focus kaleidoscopically. My theoretical adaptions are motivated by the following principles:

A topic’s identity is often unclear (Frymoyer 2017; Sánchez-Kisielewska 2023; Huovinen and Kaila 2015). This ambiguity can be exploited compositionally.

The recurrence of the same topic at different degrees of clarity can lead the listener to draw out a structural role for the topic (isotopy). This can be in lieu of clear formal processes in other parameters (harmony, rhythm, etc.).

If multiple topics are engaged, they can relate to one another in formally significant ways, from which narrative readings might be drawn.

[1.6] Topic theory has been increasingly applied to post-tonal music (see, for example, Everett 2012; Narum 2013; Frymoyer 2017; Schumann 2021; Johnson 2017; see also Donaldson 2023a). So what differentiates the music of Ligeti and Adès? Amy Bauer’s (2011) characterization of Ligeti’s late works as embodying a “cosmopolitan absurdity” captures the eclecticism of references in this music.(3) This perspective applies similarly to Adès’s music; indeed, studies of both composers’ music have explored various aspects of their highly referential aesthetic, often in a manner that demonstrates their recontextualizing of elements of the classical tradition.(4) These two composers themselves show concerns for broader intertextual references—Adès states that “It’s completely pretentious to imagine that you can do without other music” (cited in Massey 2020, 8) and Ligeti’s extensive use of written text or “jottings” in his sketches is well documented (Bernard 2011; see also Donaldson 2024). These semantically inflected prose notes reference a range of works and genres, from Gesualdo to jazz.

[1.7] Furthermore, topics inherited from the past with minimal critical treatment echo the objet trouvé central to the early surrealist aesthetics. Objets trouvés are pre-existing or readymade objects with symbolic associations that, in theory at least, leave little room for interpretating their meaning. Both composers’ music has been explored in terms of surrealist aesthetics (Everett 2009; Massey 2018; Moseley 2021; Donaldson 2022) and the classical surrealist attitude of highlighting objets trouvés’ “previously neglected associations” (Breton 1969, 26) resonates with the unlikely interactions when multiple topics are engaged.

Isotopy Applied to Music

[2.1] Previous applications of the term isotopy to the analysis of music similarly focus on dynamic understandings of a musical work’s semantics, although these studies tend to reflect the semiotician A. J. Greimas’s original theorizing of larger-scale narrative arcs (Tarasti 1994; Grabócz [1986] 1996; Grabócz 2009, 2020; Almén 2008). With reference to primarily nineteenth-century music, Márta Grabócz conceives isotopy within a broadly topical sphere, with her isotopies such as “Heroic,” “Mourning,” and “Macabre fight” modeling common successions of closely related topics within suitably nineteenth-century narrative trajectories. Robert Hatten (1994, 168–170) aligns his concept of expressive genres with Grabócz’s isotopy, similarly adopting larger-scale trajectories (such as “tragic-to-transcendent”). Hatten defines isotopy itself as similar to his expressive genres: “a higher-level expressive topic that dominates the interpretation of topics and entities in its domain” (Hatten 1994, 291). The predominant focus on later eighteenth- and nineteenth-century music is apt in each of these approaches, since the repertoire demonstrates influences from literary archetypes that draw upon similar broader narrative arcs.

[2.2] Agawu’s concept of structural rhythm is also applicable here, modeling the recurrence of smaller elements of meaning from a topical perspective. In noting that the abrupt juxtaposition of topics appears to contradict the clarity of the non-topical syntax, Agawu suggests that “a deeper-level, nonreferential process may be conceptualized,” with each topic containing an “essence” such as a “rhythm, a procedure, a melodic progression, and so on” (1991, 130). Agawu’s model is echoed in Stephen Rumph’s topical figurae (following Louis Hjemslev [1961]), which are “structural features, which articulate multiple topics yet do not themselves signify.” As a “syntactic level below the topical surface,” Rumph’s model similarly engages with topical characteristics that may be understood, after Hjemslev, on a more fundamental plane of “expression” (2014, 493–494).

[2.3] My model of isotopy engages at the level of the individual topic. Following Danuta Mirka (2014, 2), I understand topics as “musical styles and genres taken out of their proper context and used in another one.” More specifically, I assume that topics acquire a provisionally stable identity and set of characteristics which can be hierarchized into levels of specificity (following Frymoyer 2017). By adopting an explicitly semantic mode of listening (Chion 1994, 28; Tuuri and Eerola 2012), a listener follows the dynamic emergence and disintegration of topics across a

[2.4] This analytical approach relies upon one or more topics’ strong salience across a single work in this repertoire. An isotopic analysis builds a narrative rooted in topical conventions without recourse to tonal norms or narrative schema while allowing space for engagement with such theories. Such an understanding contrasts with approaches to topics’ relationship to form in common-practice repertoire, which tend to either rely on a degree of subservience to tonal syntax (Agawu 1991; Caplin 2005) or a mapping onto a larger-scale narrative schema, such as Hatten’s expressive genres (1994) and Byron Almén’s (2008) adaption of Northrop Frye’s four narrative archetypes of romance, tragedy, irony, and comedy. Indeed, a model of multiple individual guiding topics traceable over a larger scale starkly differs from the almost collage-like sequence of topics in eighteenth-century music, reflected in Ratner’s characterization of Mozart as “the greatest master at mixing and coordinating topics, often in the shortest space and with startling contrast” (1980, 27).

[2.5] Topics developing and disintegrating over long spans of time with relatively limited juxtaposition, however, is a familiar occurrence in twentieth-century music. For example, Scott Schumann traces the transformation of the French overture topic to the ombra in Stravinsky’s Apollon musagète (2021, 168–69); Amy Bauer follows the varying appearances of the Lament topic in Ligeti’s Trio for Violin, Horn, and Piano (2011, 181–185); David Hier explores different degrees of references to a broader “idealized Austro-German romantic music” (Hier 2022) in Wolfgang Rihm’s String Quartet No. 5, Ohne Titel; and in a previous article I trace the appearances of melody (akin to the “Singing Style”) in Georg Friedrich Haas’s de terrae fine (Donaldson 2021a). Broadly speaking, post-tonal music’s lack of conventional syntax and demarcating formal waypoints (such as cadences) opens a vacancy for the large-scale, dynamic appearance of topics to occupy a more significant formal role, which instead relies upon semantic convention.

[2.6] In this article, the Chorale topic acts as a connective thread across the three works I analyze, starting with a closed isotopy (i.e. single topic) in the second movement of Ligeti’s Violin Concerto. I then expand to trace isotopies of two related topics (open isotopies)(7) of the Chorale and Sound Mass in Ligeti’s Hamburg Concerto and the Chorale and Horn Call in dialogue with sonata form in the exposition of Thomas Adès’s Piano Quintet. Before turning to these examples, though, I will outline my adaption of Frymoyer’s hierarchy of topical characteristics.

Frymoyer’s Topical Hierarchy, Repurposed

[3.1] Johanna Frymoyer notes that criteria for topical identification are often left unstated (2017, 83). Her three-level weighted topical hierarchy aims to address this issue of identification. In her model, a topic’s characteristics divide into Essential features (“broad enough to encapsulate many manifestations of a topic, yet remain sufficiently narrow so as to distinguish from other dances and topics”), Frequent features (effectively a liminal category, where additional characteristics are “not essential to a topical identification…[and] help nuance its expressive content”) and Stylistically particular or idiomatic treatment (“that appear in works of a particular style, composer, or compositional circle”; Frymoyer 2017, 85). In aiming to temper the interpretive and expressive claims attributed to topical appearances, her hierarchy highlights the shifting ground of topical identification in early twentieth-century music, while simultaneously tracing the historical origin of certain topics and demonstrating how topics enjoy longevity through their adaptability. While this hierarchy captures how many twentieth-century composers adopt elements of topical material without referencing them outright—indeed, her demonstration of how an incomplete topic might signify irony is a significant analytical payoff—she does not directly address the possible synchronic application of her model (as, for example, across a single work).

[3.2] To apply this topical hierarchy synchronically, Frymoyer’s most-specific level, that concerned with the “stylistically particular or idiomatic,” requires a complementary category (2017, 96). Frymoyer’s model accounts for the historical shifting and emergence of new topics and outlines how such features can be elevated to Essential features. It applies less successfully if the topics in question show little stylistic change historically and are treated more in the manner of a late modernist objet trouvé, employed with minimal ironic intent and far from stylistically particular to the composer. For example, the Lament topic has persisted in music throughout the late twentieth century, with its central characteristics showing little change (Metzer 2009; Bauer 2011). Allowing for a provisionally stable identity, though, enables an understanding of the topic’s role in the work’s structure.

[3.3] Accordingly, I modify Frymoyer’s hierarchy slightly, offering a complementary, synchronically rooted model that reflects the formal processes in select later twentieth-century repertoire. I retain her lower two levels and general-to-specific direction, but I introduce a new, complementary category for the uppermost level to aid my differing aims. Rather than the historically oriented definition of “stylistically particular or idiomatic,” the synchronically rooted Actant (A-) level is the point at which a topic is unquestionably realized. The characteristics that constitute the Actant level may indeed be particular to a specific style, composer, or composition but, in contrast to these aspects of Frymoyer’s “stylistically particular or idiomatic” category, this level is a perceptual point of topical clarity that relates to readings of an individual work’s narrative and form.

[3.4] The term “actant,” originally coined by Greimas, is pervasive in literary narrative theory and has been previously applied to theories of musical meaning. Most significantly, as a part of his theory of musical narrative, Bryon Almén’s (2008, 74–75) adaption of James Liszka’s tripartite scheme understands the actantial level as referring to the changes in markedness and rank due to the interactions between units.(8) In effect, I propose tying agential and actantial levels together through an adaption of Frymoyer’s topical hierarchy: characteristics at the Essential and Frequent levels are akin to the agential level, whereas my Actant level aligns with Almén’s actantial level. Beyond these parallels, the interaction of multiple isotopies could be understood through Almén’s application of narrative archetypes to music. That said, although a strong degree of narrativity is inherent in the application of my conception of isotopy—or, as Michael Klein (2013, 24) puts it, “topics can get us into the musical story”—my understanding of isotopy contains no predisposition to a meaningful narrative trajectory.

[3.5] As with Frymoyer’s hierarchy, the three levels map a spectrum of meaning, such that each level’s characteristics add to the previous level to signify with increasing precision. Even if the distinctions between these three levels are occasionally fuzzy, they embody three distinct stages of perception: a passage with only Essential-level characteristics is not a topic (note that a single foundational characteristic links my examples below); a topic is suggested at the level of Frequent characteristics, but doubt remains; and only at the Actant level is the topic confirmed, akin to the introduction of “music lessons” in Eco’s example.

[3.6] To what extent does material corresponding to the Essential level signify a topic? Frymoyer (2017, 85) answers positively, writing that “These characteristics must all be present to identify a token of the topic.” In her first example, the Minuet’s Essential characteristics of triple time, a moderate tempo, and homophony (albeit maintaining a clear delineation between melody and accompaniment) “distinguish it from the slower sarabande or faster waltz, both of which have weightier second or first beats” (85). While the distinction between these three topics in isolation is immediately clear, such a restricted scope is less relevant in the expanded topical universe of the increasingly cosmopolitan later-twentieth and early-twenty-first centuries (that is, reflecting the contexts of later Ligeti and Adès rather than early- and middle-period Schoenberg). In other words, the characteristics listed above begin to point to topics beyond the Minuet in this repertoire.

[3.7] This level of generality may reflect Michael Klein’s cautionary note that, especially in music written towards the late twentieth century, “[o]ur Derridean visions of the unfixed sign pointing everywhere at once become the measure of how fragile musical meaning can be” (Klein 2005, 55). Rather than viewing “pointing everywhere” as an issue, I propose that passages corresponding to the broad Essential-level can gain—and shift—semantic significance, when understood as part of an isotopy. Following the dynamism central to isotopy, such instances can signify in two ways. In the first isolated appearance, an E-level excerpt is not topical. Frymoyer notes that the constituting characteristics of a topic are akin to Rumph’s (2014, 95–97) figurae and their “kinaesthetic-emotional experience.” Rumph’s figurae resonate with Zbikowski’s “sonic analogs” (2017, 38–41) and both echo Peircian iconic representation, where form resembles meaning in some way; as the broadest figura, then, an E-level excerpt may signify iconically. In the second instance, the same passage can be retrospectively reinterpreted as semantically significant from a topical perspective if activated as part of an isotopy. This phenomenological process is akin to the introduction of “music lessons” in Eco’s example I cited at the outset, elevating the semantic status from the isolated (potentially iconic) representation to the social and cultural (indexical) signification of a topic. Accordingly, these two modes of signification are in constant dialogue. Any reappearance of an E-level passage following the engagement with a topic is understood as synecdoche, such that the parts can represent the whole (Hatten 1994, 268).

Three Levels of a Chorale in Ligeti’s Violin Concerto

[4.1] Excerpts from the second movement of Ligeti’s Violin Concerto, titled “Aria, Hoquetus, Choral,” exemplify the three levels of the Chorale topic. The characteristics of the Chorale are relatively stable and its continued use across centuries has encouraged extended studies of the topic. Eileen Watabe and Jessica Narum trace these expressive associations through music of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, suggesting that the Chorale is relatively static in both its characteristics and expressive associations.(9) Sánchez-Kisielewska (2018) dissects the closely related Hymn topic in the eighteenth century. She notes that a foundational characteristic of both the Hymn’s and the Chorale’s liturgical role is communal singing (2018, 97); we can extrapolate that homophony is a foundational attribute of the Chorale topic, supported by Hatten (2014, 514), Eric McKee (2007, 27), and Eileen Watabe (2016, 135). This characteristic opposes complex textures and figuration, instead focusing on solemnity and unity.

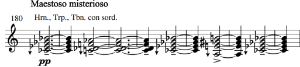

Example 1. Chorale at Actant Level, Ligeti, Violin Concerto, II mm. 180–187

(click to enlarge and listen)

[4.2] Example 1 excerpts a Chorale that appears in muted brass at the end of Ligeti’s movement. It contains many characteristics we might expect from a prototypical Chorale: four-part homophony, tertian voicings, homogeneous timbre, regular rhythm, appropriate voice-leading (primarily by tone and semitone), medium/low dynamic, and clear phrases at a regular tempo. Accordingly, this excerpt is the most fully realized version of the topic, towards which the following examples lead. Using the definitions from above, we can organize these characteristics into the following hierarchy:

CHORALE

Essential: Homophony

Frequent: Tertian voicings, regular rhythm, homogenous timbre, at least three distinct parts

Actant: Appropriate voice-leading, medium/low dynamic, clear phrases at a medium tempo, singable range and articulation, four parts

Homophony is foundational to the Chorale and therefore is the sole Essential characteristic. From a kinesthetic-emotional perspective, homophony can index a sense of togetherness (Kozak 2019, 117–120) without the cultural associations of the Chorale. At the Frequent level the coordination of the three or more parts supports the homophony, as do tertian voicings, nuancing the broader characteristic of “homophonic.” Adding multiple Actant-level (A-level) characteristics listed would confirm a Chorale, with all the A-level characteristics present further strengthening the topic.

Example 2. Stravinsky, opening of Le Tombeau de Claude Debussy for piano solo (1920), a version of which appears at the end of Symphonies of Wind Instruments

(click to enlarge and listen)

[4.3] Sánchez-Kisielewska (2018, 148) invokes specific varieties of the Hymn, such as processional or spirited Hymns. The hierarchy above centers on arguably the most common version of the Lutheran Chorale, which Sánchez-Kisielewska describes as an introspective, private chorale. Nevertheless, even within this archetypal A-level Chorale, wider historical and hermeneutic associations add further detail, reminding us to be mindful of the potential for wider historical contexts beyond my somewhat artificial, provisionally stable topic. Here, for example, Ligeti’ muted brass timbre is perhaps reminiscent of the sound of the organ swell. Furthermore, this Actant-level realization of the Chorale strongly echoes the final Chorale of Stravinsky’s Symphonies of Wind Instruments. The original piano solo version of the Chorale titled Le Tombeau de Claude Debussy (1920) is reproduced in Example 2. This reference is mentioned by Ligeti in his own article on the work(10) and, though not a direct quotation, many overlapping elements are present: the quiet brass timbre, triads with added neighboring semitones, the stepwise melodic contours, and the formal placement near the end of the movement. A Stravinskian Chorale is a “Stylistically Particular or Idiomatic” topic, akin to Frymoyer’s example of a Chopinesque Waltz. Within this context, the association of Stravinsky’s Chorale with a tribute to Debussy—the Chorale was initially written for a special edition of La Revue musicale entitled Le Tombeau de Claude Debussy—brings new funereal associations into the hermeneutic net.

Example 3. Chorale with Frequent-level characteristics, Ligeti, Violin Concerto, II,

(click to enlarge and listen)

[4.4] At the Frequent level (F-level) a topic is suggested but remains unclear. For the Chorale, F-level characteristics are tertian voicings, regular rhythm, and homogeneous timbre. Although these characteristics individually begin to point towards the Chorale—even more so in combination with each other, and alongside the Essential quality of homophony—they do not yet confirm the topic. Example 3 is an excerpt from the same movement of Ligeti’s Concerto that contains all the E-and F-level characteristics, but because of its loud dynamic, high tessitura, and parallel voice leading, is not an archetypal Chorale idiom.(11) Nevertheless, enough elements point towards “Chorale” to make it a useful description, though not without a degree of hesitation relative to the clarity of Ex. 1.(12)

Example 4. Essential-level Chorale, Ligeti, Violin Concerto II, mm. 28–31

(click to enlarge and listen)

[4.5] Example 4 is the entry of the accompanying viola to the solo violin near the opening of the movement. Through their coordination of primary attacks, they create homophony, satisfying the E-level characteristic. No F-level characteristics are satisfied, however: the voicing is not tertian (a ninth followed by two fifths) and it remains in only two parts. While the A-level attributes of the medium/low dynamic and singable range are satisfied, the lack of F-level characteristics restricts it to the E-level, as the F-level characteristics cannot be skipped. Let us now turn to the relationship between these three examples across the movement.

Closed Isotopies

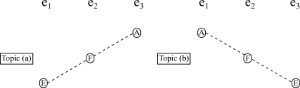

Example 5. Two abstract closed isotopies. Towards a realization of a topic (a) and a disintegration away from an initially clear appearance of topic (b)

(click to enlarge)

[5.1] Example 5 maps two abstract isotopies across three musical events (e1, e2, e3) and the three levels, in opposite directions. I conceive a musical event (e) broadly, as anything from a group of pitches to a phrase (or even material occupying a larger section) and contains one or more characteristics corresponding to the respective level. (For ease of representation, I will only include short excerpts in the following examples, although some of these may be representative of larger sections.) In Ex. 5a, the topic is increasingly realized up to Actant level by the third event, retrospectively elevating the signifying status of the E-and F-levels. In Ex. 5b the topic is immediately established early in the work and then disintegrates. Although the Actant level is defined as the point when the topic becomes active in the discourse, reaching the Actant level is not necessarily required for a topic to constitute a significant part of a work’s expressive trajectory. The Frequent level indicates that the listener begins to suspect a topic, such that topics at this level still contribute to the discourse, albeit less strongly. An Actant-level topic can appear without its respective F and E levels.

Example 6. Opening aria theme of Ligeti, Violin Concerto, II. No E- or F-level Chorale characteristics

(click to enlarge and listen)

Example 7. A closed isotopy of the Chorale topic across Ligeti, Violin Concerto, II

(click to enlarge and listen)

[5.2] Let us return to the three excerpts from Ligeti’s Violin Concerto with an isotopic framework. Ligeti’s movement opens with a legato solo violin statement of the theme, excerpted in Example 6. This opening monophonic line is clearly not a Chorale due to its lack of homophony, although characteristics of the Chorale’s higher levels are present: medium/low dynamic, clear phrases at a medium tempo, and a regular rhythm. Example 7 maps the Chorale isotopy of the three excerpts discussed above. The example is not comprehensive, as appearances of E-and F-level Chorales appear throughout, though the progression towards a realization of the Chorale topic is clear. The introduction of homophony at the first event (e1) begins this process (see Ex. 4), but little indicates a Chorale. At e2 (see Ex. 3) the ocarinas now play tertian harmonies with homogeneous timbres, though they are still too high and their overt parallelism directly opposes any clear voice leading. A Chorale can be engaged at this point, though the topic remains ambiguous. Event 1 (e1) is retrospectively reinterpreted as an anticipation of key Chorale characteristics, although “Chorale” as a rewarding lens is only cemented at e3, when the Chorale appears at Actant level (see Ex. 1). The Chorale topic gradually emerges over the movement, creating a kaleidoscopic variation on the Chorale cantata.

Open Isotopies

[6.1] This single-topic analysis models a discrete conception of isotopy, yet few topics enact such a lonely path. Even if multiple topics exist in a work, their constituting characteristics are not always unique to each topic, instead overlapping such that one topic can easily drift into another. A topic may require only a minor change to its characteristics to gently move to another topic, introducing a new isotopic path out of the previous one. After Eco, I term this occurrence of two or more overlapping isotopies with at least one shared event open isotopies.

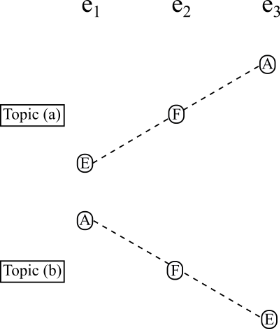

Example 8. Two isotopies in a more open relationship

(click to enlarge and listen)

[6.2] Example 8 maps an example of two abstract open isotopies. In this example and the musical examples below, all the topics are realized at A-level (but again, this is not required). The event sequence of topic (a) is the same as the closed isotopy of Ex. 5a, gradually realizing the topic up to the Actant level. In the abstract open model, though—that is, with the same three musical events—a second topic follows the reverse path, as in Ex. 5b’s disintegration of a topic from the Actant level—a form of topical liquidation. At each e, the listener re-orients themselves with respect to topics (a) and (b). To achieve this, at least one characteristic of the two topics must overlap. At e2, neither is realized: topic (a) is projected while topic (b) begins to disappear. Both are on the threshold but follow different paths, one emerging, the other disintegrating. As outlined below, given the listener dependency of a topic, perhaps only one isotopy is identified by the listener. As such, depending on their familiarity with the imported genres, one listener familiar with topic (a) might center on its successful realization towards the end, a triumphant arrival, whereas another listener focused on topic (b) may extract some tragic connotations from the dissolution of that topic. Accordingly, if only one topic is engaged with by the listener this model can account for dramatically different hermeneutic interpretations of the same music.

[6.3] Mapping the interaction of two expressively unrelated topics across a single work is close to Hatten’s concept of troping (2004; 2014). Hatten interpret merged topics as generating fresh meaning. When taking the more dynamic understanding of isotopy, repeated iterations of two topics at their respective F-levels—such as e2 in Ex. 8—embodies elements of merging and therefore troping. Accordingly, open isotopy has parallels with Almén and Hatten’s tropological narratives, where multiple strands are “juxtaposed in a way that emphasizes their similarity or difference” (2013, 71). Furthermore, one could model Hatten’s tropological axes more closely through open isotopies, such as his axis of tropological productivity (the degree to which a topic or trope is used throughout a composition, see Hatten 2014). Scott Schumann (2021, 155) frames productivity—one of Hatten’s four axes—as the one which governs global musical structures. The complementary axis referring to local musical structures is dominance, or the degree of prominence for a topic within its musical environment. This category is the most relevant here. In my abstract open isotopy of Ex. 8, topic (a) has a high degree of dominance over topic (b) at e3. By e3 topic (b) is retrospectively understood to have had a high degree of dominance over topic (a) at e1. More broadly, such trajectories can be aligned with Almén’s narrative archetypes, especially the victory/defeat paradigm (2008, 65–66). Open isotopies can trace these processes in action on a more granular level.

[6.4] As an example of such an interaction, Ligeti’s Hamburg Concerto (1998–1999, rev. 2003) contains prominent topics of the Sound Mass and the Chorale. The interaction of these two topics is a striking example of open isotopies as their poetic associations differ distinctly, but they share multiple characteristics. The markedly different expressive associations—the Chorale tapping into a long history of religious communal singing, in contrast to the Sound Mass’s association with postwar high modernism(13)—point to dramatically juxtaposed connotations. This contrasts contrast in the topics’ social contexts and functions is particularly striking given their multiple common musical characteristics.

[6.5] Topicalizing the Sound Mass in Ligeti’s music has been suggested previously by Yayoi Uno Everett (2009, 29) and Robert Hatten (2018, 280). Outside of topic theory, Jason Noble et al. (2020) have explored mappings between the perceptual and semantic domains. Combining perceptual research and acoustic analysis, they identify consistent musical characteristics and semantic associations across a range of listeners, often related to associations of the Sound Mass in film and television music, highly suggestive of an emerging topical use. Indeed, the Sound Mass utilized as a conventionalized imported genre surrounded by unrelated material—drawing upon associations from the original contexts of both film/television music and concert works—occurs increasingly frequently. This topical treatment is distinct from Sound Mass textures used as a singular structural device—a shift particularly evident in Ligeti’s stylistic change in later works. His works written in the late 1950s and 60s—such as Apparitions (1959), Atmosphères (1961), Ramifications (1968–69), and the Requiem (1963–65)—eschew a clear sense of pitch, exploring other elements rooted in his experience in the West German Radio (WDR). His later use of Sound Mass as a conventionalized imported genre fundamentally changes the topic’s role in Ligeti’s compositional topical aesthetic.

[6.6] My understanding of the conventionalized coded characteristics of the Sound Mass is rooted in Douglas et al.’s definition:

Sound mass exists when the individual identities of multiple sound events or components are attenuated and subsumed into a perceptual whole, which nevertheless retains an impression of multiplicity. Typically this involves one or more parameters of sound—for example, rhythmic activity, pitch organization, or spectral content—attaining a degree of density, complexity, and/or homogeneity that is perceived as saturation. (Douglas, Noble, and McAdams 2016, 287)

Crucially, relative to the Chorale topic, the pitches of the Sound Mass are not perceived as individuals. Likewise, Sound Mass obscures the Chorale’s regular rhythm. Noble later adds to this definition, focusing on perceptual issues:

A perceptually dense and homogeneous auditory unit integrating multiple sound events or components while retaining an impression of multiplicity. Although their acoustical correlates may be highly complex, sound masses are perceptually simple because they resist perceptual segmentation in one or more parameters (e.g., pitch, rhythm, timbre). (Noble 2018, 8)

That a Sound Mass is “perceptually simple” is significant in relation to other topics, as it subsumes other parameters—and consequently other topics’ characteristics—into one perceptual element.

[6.7] Nevertheless, from these clear characteristics in multiple parameters we can hierarchize the topic:

SOUND MASS

E: Slow-moving/near-static texture with unclear meter

F: Several distinct layers of pitches (more than a simple chord), rhythms, or timbres, often closely spaced (metrically or in register) or multiple simultaneous (yet separate) groups(14)

A: Sound events subsumed into a perceptual whole through the combination of many layers of pitch, rhythm, or timbre

The topics of the Chorale and Sound Mass share the characteristic of multiple independent lines, but, unlike the Chorale, the Sound Mass subsumes the voices into a perceptual whole with imperceptible voice-leading. Similarly, while the Chorale has a clear meter—even phrases at the A-level— the Sound Mass’s E-level characteristic is a slow-moving texture with an unclear meter.

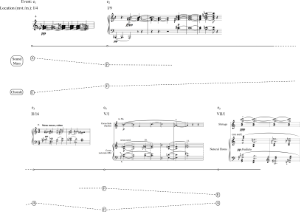

Example 9. The interaction between the Sound Mass and Chorale topics across movements in Ligeti, Hamburg Concerto

(click to enlarge and listen)

[6.8] Example 9 maps open isotopies of the two topics in Ligeti’s Hamburg Concerto.(15) The work opens with a clear Sound Mass topic, after which the Chorale gains prominence over the course of work. Event 1 (e1) (I/4) expresses the Sound Mass at Actant level; its peak at seven pitches effectively becomes a perceptual whole. This layering of many pitches is homophonic, an Essential-level characteristic of the Chorale. The Chorale, however, is not notably in effect. The harmonies open out in e2 (the solo horn line is missing from this excerpt), from an E-

[6.9] Event 3 (e3) is a clear Actant-level Chorale, with no suggestions of the Sound Mass topic. The Chorale topic is now unambiguously engaged and e1 is retrospectively reinterpreted as contributing part of a Chorale. Event 4 (e4, the opening of the fifth movement “Spectra”) elides the two topics differently to e2: the established rhythm is more regular, but the tertian harmonies of the obbligato horns are undermined by the solo horn’s pitches, suggestive of the Sound Mass. Event 5 (e5) excerpts the opening of the seventh movement, Hymnus, which, perhaps unsurprisingly returns to the A-level Chorale, although now the ppp flutter-tonguing creates a strained effect. Although the Chorale characteristics are at the forefront, a listener may engage the Sound Mass through synecdoche.

[6.10] To identify this slight shifting between abstract musical material without engaging an isotopic framework would overlook the striking interactions between these topics. Instead, such an analysis might conclude the effect of shifting between clear, four-part tertian harmony and a dense layering of pitches as minimal. Applying an isotopic lens, though, reframes this shift as a kaleidoscopic effect between the diverging expressive associations of the Chorale and the Sound Mass. Tracing these topics—or even simply identifying one rather than both—depends on the different levels of listener experience with Chorales and Sound Mass music, which could be affected by an external force of the generic framing or the wider reception of the work. To use a somewhat simplified hypothetical: placing the Hamburg Concerto in a concert alongside works of Penderecki and Xenakis would likely motivate listeners to prioritize the Sound Mass elements, whereas framing the Concerto in a concert alongside works with significant chorales, even themed as such (perhaps Berg’s Violin Concerto or Stravinsky’s Symphonies of Wind Instruments) would encourage listeners primarily to home in on the Chorale characteristics. Applying the concept of open isotopy melds these multiple simultaneous hermeneutic perspectives, each with its own trajectories in the work.

Thomas Adès’s Piano Quintet: Open Isotopies and Sonata Form

[7.1] The resulting trajectories from these isotopies can resemble elements of familiar narrative schemata, such as Hatten’s tragic-to-transcendent or Almén’s narrative archetypes. My approach arrives at such conclusions by building systematically upwards from small-scale observations. This method can construct isotopies that map onto temporal schemata that are perhaps less explicitly motivated by narrativity, such as sonata form.(16)

[7.2] In his interviews and program notes, Adès describes elements of sonata form in his Chamber Symphony (1990),

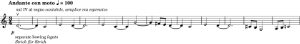

[7.3] Before turning to the Quintet, let us establish the Horn Call’s hierarchy of characteristics. Raymond Monelle identifies Siegfried’s horn call as enshrining “all the features of the topic, except that its call is a monody” (2006, 95). Wagner’s call, and all of Monelle’s other examples, contain prominent rising gestures, which are suitable as an E-level characteristic. As Monelle considers Wagner’s example as a Horn Call, we cannot consider homophony as an E-level characteristic. Homophony is better reserved for the F level, to which I add prominent vertical intervals of fourths or fifths (requiring homophony). A medium tempo and medium tessitura (Monelle specifies the third register of the horn as idiomatic) bring the topic closer to the A-level. The Actant characteristics of horn dyads and triads at a loud dynamic confirm the topic. Clear phrases demarcated through sustained pitches or silence and a sense of triple meter (echoing a primary characteristic of the Hunt topic; the majority of Monelle’s examples are in compound meter) are less central, but when present further solidify a Horn Call topic.

HORN CALL

E: Prominent ascending motion(19)

F: medium-loud dynamic,(20) prominent vertical intervals of fourths or fifths in homophony, medium tempo, mid tessitura

A: horn dyads/triads, clear end of phrase (through sustained pitch(es) or silence), sense of triple meter

Example 10. The Exposition of Adès, Piano Quintet, showing two interacting isotopies of the Horn Call and Chorale

(click to watch video in new tab)

[7.4] Example 10 maps these two topics’ isotopies across the Quintet’s Exposition.(21) As with the previous examples, the excerpts are only a selection of the most prominent topic-engaging moments, with some instances containing both topics and others only one. The opening of the Quintet provides an example of a tonal Horn Call in a post-tonal soundworld. The opening two G major and C major triads—albeit disrupted in the third chord—are even strong enough to suggest a key.(22) This opening satisfies the Actant level of the Horn Call. Despite the clarity of topic at the opening, the three chords are also homophonic, tertian voicings, a homogenous timbre, and regular rhythm—thus satisfying the Frequent-level characteristics of the Chorale. The slightly awkward voice-leading (including the rising major thirds in the lowest voice) and clear phrases restrict the opening to the Frequent level and the identification as a Horn Call overshadows any engagement with the Chorale for now, a form of tropological dominance.

[7.5] The lower line of Example 10 maps the key formal points of the Exposition. The Horn Call topic is central to the Main Theme, appearing clearly at the Actant level (e1).(23) As Stoecker notes, this opening Horn Call is an aligned cycle of ⟨ 2, 3, 4 ⟩. In an aligned cycle, each voice rises by a consistent interval, read from top to bottom, such that ⟨ 2, 3, 4 ⟩ is three parallel interval cycles of a tone, minor third, and major third (2014, 32). Chorale characteristics are in the shadow of the Horn Call throughout the Main Theme, only retrospectively becoming important later in the

[7.6] As the movement progresses into the transition section, the A-level characteristics of the Horn Call begin to disappear, replaced by a burgeoning Chorale. At e3 the aligned-cycle Horn Call pattern appears in dialogue across the ensemble, extending beyond the opening three-chord Horn Call and, crucially, shifting to the Chorale’s characteristic of a clear phrase. This liquidation of the Horn Call continues into e4: the rising pattern in the first violin maintains the topic’s E-level characteristic, as does (more loosely) the rising C-

[7.7] This confirmation of the Chorale signals the beginning of the Subordinate Theme area, helping listeners retrospectively to understand the previous instances of Chorale characteristics as emerging from the tropological dominance of the Horn Call. These Chorale elements continue to pervade the ST, although a similar liquidation of topical characteristics occurs, with new Horn Call characteristics beginning to undermine the Chorale’s clarity. At e6, the topic lowers to the Frequent level, with the fff, parallel chords similar to the ocarina Chorale in Ligeti’s Violin Concerto in Ex. 3. A more clearly aligned cycle of ⟨1, 2, 1, 2⟩ returns here, although it is disrupted in the final two sonorities. At e7 a markedly different idea appears, enacting a

[7.8] The fff rising pattern first appearing at e4 returns extensively at e9, with a sudden outburst of Horn Call characteristics at e10: the music is loud, ascending, homophonic, and loosely triadic, all in a mid tessitura. All the A-level characteristics are lacking, however, and this fleeting return to the Horn Call topic is soon interrupted with a prominent return to full Chorale at e11. Although extremely high and ppp, all the Chorale characteristics are satisfied, even ending the four-bar phrase with a cadential gesture. As the energy dissipates, so does the Chorale, with the final rolling dialogue of F-C and

[7.9] In sum, rather than considering the Horn Call and Chorale in isolation, tracing their constituent characteristics across the exposition draws out a more entwined, kaleidoscopic interaction that reflects the familiar arc of a sonata exposition, with topical clarity in place of familiar tonal landmarks. Accordingly, Adès’s comment that his music is “naturally always transitioning, always slipping” resonates only to an extent in the topical sphere (Adès and Service 2012, 75; see also Rupprecht 2021), since the “slippery” topics settle at key moments in the form. The homophony inherent in the aligned cycles that pervade the work acquires a hermeneutic role besides controlling the harmony, such that the cycles interact with other parameters to bring the Horn Call and Chorale in and out of focus at key points. While the aligned cycle technique is central to the Quintet’s harmonic language, tracing the isotopies of these two topics across the two themes of the sonata exposition simultaneously demonstrates variation within coherence, with the same harmonic process a foundational characteristic of two markedly different expressive directions.

Conclusion

[8.1] “Proust,” Eco writes in a later reflection on the analytical application of isotopy, “could read a railroad timetable and find in the names of the Valois region sweet, labyrinthian echoes of the Nervalian voyage in search of Sylvie” (1980, 155). There may always be one reader who can squeeze a gripping story out of something as seemingly narratively bland as a list of place names and train departure times. This example reminds us of the perceiver’s role in creating meaning and that given the range of musical characteristics that contribute to each topic across the topical universe, an isotopy of many topics may be extracted from the webs of semantically rich works. And, following Proust’s lead, perhaps a listener could trace such isotopies from seemingly abstract music.

[8.2] My analytical application of isotopy, however, leans heavily on stable topical convention to temper such a hyper-plurality. Although different readers or listeners could theoretically bring different topical lenses to form strikingly different understandings of a basic invariant text to the degree of Proust’s reading of train timetables, a topic’s convention is necessary to maintain intersubjective communication. Accordingly, as conventionalized coded signs rooted in a canon, familiar to both composer and listener, identifying a work’s isotopy can recapture a similar effect to the topic of “music lesson” in Eco’s example I cited at the outset, cohering semantically what may, from the perspective of other analytical methods, appear disparate.

[8.3] Although this analytical method could be applied beyond my current narrow repertoire choices, my interpretation of these works through an isotopic framework brings into focus elements of style. These three works represent music composed in recent decades that draws upon topics and topic-like references, such as by Sofia Gubaidulina, John Adams, Kaija Saariaho, and Wolfgang Rihm. Such music embodies an aesthetic of textuality somewhat distinct from the collage-based experiments common in the 1960s. Rather than juxtapose overt references to other music, central to such an aesthetic are more subtle footprints of the past, from the near-timelessness of Hymns and Chorales to the more recent Sound Mass and its associations with high modernism or, indeed, the natural world (e.g., clouds). Rather than being quoted, these topics are often woven in as an integral part of the work’s form and expression, skirting an overtness of reference without recourse to irony or satire. This topical treatment contrasts with the aesthetic motivations for Frymoyer’s and Schumann’s modeling of topics in post-tonal music, with the former focusing on the role of irony in relatively demarcated topics in Schoenberg and the latter viewing characteristically Stravinskian juxtapositions from a topical standpoint. In other words, along with Frymoyer’s and Schumann’s writings, this article demonstrates not only the continued vitality of topics in twentieth-century music, but adds another perspective on how composers in the twentieth century drew upon such familiar material as a central communicative principal.

James Donaldson

Faculty of Music

University of Oxford

St. Aldate’s

Oxford, OX1 1DB

james.donaldson@magd.ox.ac.uk

Works Cited

Adès, Thomas, and Tom Service. 2012. Full of Noises: Conversations with Tom Service. Faber.

Agawu, Kofi. 1991. Playing with Signs: A Semiotic Interpretation of Classic Music. Princeton University Press. https://doi.org/10.1515/9781400861835.

Almén, Byron. 2008. Theory of Musical Narrative. Indiana University Press.

—————. 2013. “Narrative Engagement in Twentieth-Century Music.” In Music and Narrative since 1900, ed. Michael Klein and Nicholas Reyland, 59–85. Indiana University Press.

Barthes, Roland. 1974. S/Z. Translated by Richard Miller. Hill and Wang.

Bauer, Amy. 2011. Ligeti's Laments: Nostalgia, Exoticism, and the Absolute. Ashgate.

Bernard, Jonathan. 2011. “Rules and Regulations: Lessons from Ligeti's Compositional Sketches.” In György Ligeti: Of Foreign Lands and Strange Sounds, ed. Louise Duchesneau and Wolfgang Marx, 149–68. Boydell Press.

Bouliane, Denys, and Anouk Lang. 2006. “Ligeti's Six ‘Etudes Pour Piano’: The Fine Art of Composing Using Cultural Referents.” Theory and Practice 31: 159–207.

Breton, André. 1969. Manifestoes of Surrealism. Translated by Richard Seaver and Helen R. Lane. University of Michigan Press. https://doi.org/10.3998/mpub.7558.

Callender, Clifton. 2007. “Interactions of the Lamento Motif and Jazz Harmonies in György Ligeti’s Arc-en-ciel.” Intégral 21: 41–77.

Caplin, William. 2005. “On the Relation of Musical Topoi to Formal Function.” Eighteenth Century Music 2 (1): 113–24. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1478570605000278.

Chion, Michel. 1994. Audio-Vision: Sound on Screen. Translated by Claudia Gorbman. Columbia University Press.

Donaldson, James. 2021a. “Melody on the Threshold in Spectral Music.” Music Theory Online 27 (2). https://doi.org/10.30535/mto.27.2.9.

—————. 2021b. “Topics, Double Coding, and Form Functionality in Thomas Adès’s Piano Quintet.” Tempo 75 (298): 41–51. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0040298221000383.

—————. 2021c. “Topics, Form, and Expression in the Music of György Ligeti and Thomas Adès.” PhD diss., McGill University.

—————. 2022. “Living Toys in Thomas Adès's Living Toys: Transforming the Post-Tonal Topic.” Music Theory Spectrum 44 (2): 155–72. https://doi.org/10.1093/mts/mtab011.

—————. 2023a. “Second-Order Topics and Prokofiev's String Quartets.” Music Analysis 42 (2): 227–61. https://doi.org/10.1111/musa.12218.

—————. 2023b. “Sketching between the Chorale and the Sound Mass in Ligeti's Hamburg Concerto.” Mitteilungen der Paul Sacher Stiftung 36: 38–43.

—————. 2024. “Sketching Musical Meaning? Case Studies from Ligeti's Late Works.” Journal of Musicology 41 (3).

Douglas, Chelsea, Jason Noble, and Stephen McAdams. 2016. “Auditory Scene Analysis and the Perception of Sound Mass in Ligeti’s Continuum.” Music Perception 33 (3): 287–305. https://doi.org/10.1525/mp.2016.33.3.287.

Eco, Umberto. 1979. The Role of the Reader: Explorations in the Semiotics of Texts. Indiana University Press.

—————. 1980. “Two Problems in Textual Interpretation.” Poetics Today 2 (1a): 145–61. https://doi.org/10.2307/1772358.

—————. [1962] 1989. The Open Work. Harvard University Press.

Everett, Yayoi Uno. 2009. “Signification of Parody and the Grotesque in György Ligeti’s Le Grand Macabre.” Music Theory Spectrum 31 (1): 26–56. https://doi.org/10.1525/mts.2009.31.1.26.

—————. 2012. “ ‘Counting Down’ Time: Musical Topics in John Adams’ Doctor Atomic.” In Music Semiotics: A Network of Significations, ed. Esti Sheinberg, 263–73. Ashgate.

Frymoyer, Johanna. 2017. “The Musical Topic in the Twentieth Century: A Case Study of Schoenberg’s Ironic Waltzes.” Music Theory Spectrum 39 (1): 83–108. https://doi.org/10.1093/mts/mtx004.

Gallon, Emma. 2013. “Narrativities in the Music of Thomas Adès: The Piano Quintet and Brahms.” In Music and Narrative since 1900, ed. Michael Klein and Nicholas Reyland, 216–33. Indiana University Press.

Grabócz, Márta. [1986] 1996. Morphologie des oeuvres pour piano de Liszt: influence du programme sur l'évolution des formes instrumentales. Editions Kimé.

—————. 2009. Musique, narrativité, signification. L'Harmattan.

—————. 2020. “From Music Signification to Musical Narrativity.” In The Routledge Handbook of Music Signification, ed. Esti Sheinberg and William P. Dougherty, 197–206. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781351237536-17.

Greimas, Algirdas Julien. [1976] 1988. Maupassant: Practical Exercises. Translated by Paul Perron. John Benjamins Publishing Company.

Hatten, Robert. 1994. Musical Meaning in Beethoven: Markedness, Correlation, and Interpretation. Indiana University Press.

—————. 2004. Interpreting Musical Gestures, Topics, and Tropes: Mozart, Beethoven, Schubert. Indiana University Press.

—————. 2014. “The Troping of Topics in Mozart’s Instrumental Works.” In The Oxford Handbook of Topic Theory, ed. Danuta Mirka, 514–36. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199841578.013.0020.

—————. 2018. A Theory of Virtual Agency for Western Art Music. Indiana University Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv512trj.

Hentschel, Frank, and Gunter Kreutz. 2021. “The Perception of Musical Expression in the Nineteenth Century: The Case of the Glorifying Hymnic.” Music & Science 4: 1–28. https://doi.org/10.1177/20592043211012396.

Hepokoski, James, and Warren Darcy. 2006. Elements of Sonata Theory: Norms, Types, and Deformations in the Late Eighteenth-Century Sonata. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195146400.001.0001.

Hier, David. 2022. “Becoming and Disintegration in Wolfgang Rihm’s Fifth String Quartet, Ohne Titel.” Music Theory Online 28 (2). https://doi.org/10.30535/mto.28.2.3.

Hjelmslev, Louis. 1961. Prolegomena to a Theory of Language. Translated by Francis J. Whitfield. University of Wisconsin Press.

Huovinen, Erkki, and Anna-Kaisa Kaila. 2015. “The Semantics of Musical Topoi: An Empirical Approach.” Music Perception 33 (2): 217–43. https://doi.org/10.1525/mp.2015.33.2.217.

Iverson, Jennifer. 2010. “The Emergence of Timbre: Ligeti's Synthesis of Electronic and Acoustic Music in Atmosphères.” Twentieth-Century Music 7 (1): 61–89. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1478572211000053.

Johnson, Thomas. 2017. “Tonality as Topic: Opening A World of Analysis for Early Twentieth-Century Modernist Music.” Music Theory Online 23 (4). https://doi.org/10.30535/mto.23.4.7.

Klein, Michael. 2005. Intertextuality in Western Art Music. Indiana University Press.

—————. 2013. “Musical Story.” In Music and Narrative since 1900, ed. Michael Klein and Nicholas Reyland, 3–28. Indiana University Press.

Kozak, Mariusz. 2019. Enacting Musical Time: The Bodily Experience of New Music. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780190080204.001.0001.

Levy, Benjamin R. 2017. Metamorphosis in Music: The Compositions of György Ligeti in the 1950s and 1960s. Oxford University Press.

Ligeti, György. 1993. “Rhapsodische, unausgewogene Gedanken über Musik, besonders über meine eigenen Kompositionen.” Neue Zeitschrift für Musik 153 (1): 20–29.

—————. [1992] 2007. “Concerto pour Violin.” In György Ligeti: L’atelier du Compositeur. Edited by Philippe Albèra, Catherine Fourcassié, and Pierre Michel, 303–306. Contrechamps.

Massey, Drew. 2018. “Thomas Adès and the Dilemmas of Musical Surrealism.” Gli spazi della musica 7.

—————. 2020. Thomas Adès in Five Essays. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780199374960.001.0001.

McKee, Eric. 2007. “The Topic of the Sacred Hymn in Beethoven’s Instrumental Music.” College Music Symposium 47: 23–52.

Metzer, David. 2009. Musical Modernism at the Turn of the Twenty-First Century. Cambridge University Press.

Mirka, Danuta. 2014. “Introduction.” In The Oxford Handbook of Topic Theory, ed. Danuta Mirka, 1–47. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199841578.013.002.

Monelle, Raymond. 2006. The Musical Topic: Hunt, Military, and Pastoral. Indiana University Press.

Moseley, Brian. 2021. “Musique automatique? Adèsian Automata and the Logic of Disjuncture.” In Thomas Adès Studies, ed. Edward Venn and Philip Stoecker, 163–87. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108761451.009.

Narum, Jessica. 2013. “Sound and Semantics: Topics in the Music of Arnold Schoenberg.” PhD diss., University of Minnesota.

Nattiez, Jean Jacques. [1975] 1990. Music and Discourse: Toward a Semiology of Music. Princeton University Press.

Noble, Jason. 2018. “Perceptual and Semantic Dimensions of Sound Mass.” PhD diss., McGill University.

Noble, Jason, Etienne Thoret, Max Henry, and Stephen McAdams. 2020. &ldquoSemantic Dimensions of Sound Mass Music: Mappings between Perceptual and Acoustic Domains.” Music Perception 38 (2): 214–42. < a href='https://doi.org/10.1525/mp.2020.38.2.214'>https://doi.org/10.1525/mp.2020.38.2.214.

Rastier, François. 1972. “Systématique des isotopies.” In Essais de sémiotique poétique, ed. A. J. Greimas, 80–106. Larousse.

Ratner, Leonard. 1980. Classic Music: Expression, Form and Style. Schirmer Books.

Rumph, Stephen. 2014. “Topical Figurae: The Double Articulation of Topics.” In The Oxford Handbook of Topic Theory, ed. Danuta Mirka, 493–513. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199841578.013.019.

Rupprecht, Philip. 2021. “‘Chronically Volatile’: Gesture in Adès’s Living Toys and America: A Prophecy.” In Thomas Adès Studies, ed. Edward Venn and Philip Stoecker, 1–26. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108761451.002.

Sánchez-Kisielewska, Olga. 2018. “The Hymn as a Musical Topic in the Age of Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven.” PhD diss., Northwestern University.

—————. 2023. “On Figaro’s Alleged Minuet and Some Challenges and Opportunities of Topic Theory.” Music Theory Spectrum 45 (1): 89–99. https://doi.org/10.1093/mts/mtac027.

Schumann, Scott C. 2021. “Tropological Interaction and Expressive Interpretation in Stravinsky’s Neoclassical Works.” Music Theory Spectrum 43 (1): 153–71. https://doi.org/10.1093/mts/mtaa015.

Searby, Michael D. 2010. Ligeti’s Stylistic Crisis: Transformation in his Musical Style, 1974–1985. Scarecrow Press.

Searby, Mike. 2012. “To the Future or the Past? Ligeti’s Stylistic Eclecticism in His Hamburg Concerto.” Contemporary Music Review 31 (2–3): 239–46. https://doi.org/10.1080/07494467.2012.717365.

Sonesson, Göran. 2017. “Greimasean Phenomenology and Beyond: From Isotopy to Time Consciousness.” Semiotica 2017 (219): 93–113. https://doi.org/10.1515/sem-2017-0084.

Stoecker, Philip. 2014. “Aligned Cycles in Thomas Adès's Piano Quintet.” Music Analysis 33 (1): 32–64. https://doi.org/10.1111/musa.12019.

Tarasti, Eero. 1994. A Theory of Musical Semiotics. Indiana University Press.

Tuuri, Kai, and Tuomas Eerola. 2012. “Formulating a Revised Taxonomy for Modes of Listening.” Journal of New Music Research 41 (2): 137–52. https://doi.org/10.1080/09298215.2011.614951.

Venn, Edward. 2014. “Thomas Adès’s ‘Freaky Funky Rave.’” Music Analysis 33 (1): 65–97. https://doi.org/10.1111/musa.12020.

—————. 2015. “Thomas Adès and the Spectres of Brahms.” Journal of the Royal Musical Association 140 (1): 163–212. https://doi.org/10.1080/02690403.2015.1008867.

—————. 2021a. “Adès and Sonata Forms.” Tempo 75 (298). https://doi.org/10.1017/S0040298221000371.

—————. 2021b. “Findings, Keepings, and Borrowings: Uncanny Intertextuality in Thomas Adès’s Powder Her Face.” In Intertextuality in Music: Dialogic Composition, ed. Violetta Kostka, Paulo F. de Castro, and William A. Everett, 217–228. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003092834-19.

Watabe, Eileen. 2015. “Chorale Topic from Haydn to Brahms: Chorale in Secular Contexts of the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries.” DMA diss., University of Northern Colorado.

—————. 2016. “Chorale for One: Personal Expression in Nineteenth-Century Chorale Topic.rdquo; Yale Journal of Music & Religion 2 (1): 135–70. https://doi.org/10.17132/2377-231X.1036.

Wörner, Felix. 2017. “Tonality as “Irrationality Functional Harmony”: Thomas Adès’s Piano Quintet.” In Tonality Since 1950, ed. Felix Wörner, Ullrich Scheideler, and Philip Rupprecht. Franz Steiner Verlag, 295–311. https://doi.org/10.25162/9783515115896.

Zbikowski, Lawrence. 2017. Foundations of Musical Grammar. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780190653637.001.0001.

Discography

Discography

Adès, Thomas, and the Arditti Quartet. 2005. “Piano Quintet: 1” in Adès: Piano Quintet & Schubert: Trout Quintet. EMI Classics.

Gawriloff, Saschko, Pierre Boulez, and Ensemble Intercontemporain. 1994. “Violin Concerto (1992): II. Aria, Hoquetus, Choral” in Boulez Conducts Ligeti: Concertos for Cello, Violin, Piano. Deutsche Grammophon.

Neunecker, Marie Luise, Reinbert de Leeuw, and the AKSO Ensemble. 2003. “Ligeti, Hamburg Concerto” in The Ligeti Project: IV. Teldec Classics.

Salonen, Esa-Pekka, and the London Sinfonietta. 1989. Esa-Pekka Salonen Conducts Stravinsky. Sony Music Entertainment.

Footnotes

1. Of course, the parallel between these examples is not exact, since Eco’s interjection of the idea of “music lessons” makes sense out of a seemingly nonsensical conversation that has begun in media res, and Agawu’s application of the March topic is a subtler effect, adding meaning to a more neutral (but otherwise coherent) beginning. Nevertheless, it is significant that both introduce a new concept to semantically reframe the material in retrospect.

Return to text

2. For longer literary analyses drawing upon isotopy, see Greimas’s ([1976] 1988) analysis of Guy de Maupassant’s Deux Amis (1882), Eco’s (1979, 200–260) analysis of Alphonse Allais’s “Un drame bien parisien”, and François Rastier’s (1972) analysis of Mallarmé’s poem “Salut”. The five “codes” Roland Barthes’s (1974) traces through Balzac’s “Sarrasine” in his influential S/Z have similarities to Greimas’s concept.

Return to text

3. For an example of Ligeti discussing some of his own influences and possible references, see Ligeti 1993.

Return to text

4. On Ligeti, see Bouliane and Lang 2006; Callender 2007; Everett 2009; Searby 2010; Bauer 2011; Searby 2012; Donaldson 2024. On Adès, see, Venn 2014, 2015, 2021a, 2021b; Massey 2020; Donaldson 2022. On both composers, see Donaldson 2021c.

Return to text

5. On the phenomenological underpinnings of Greimas’s understanding of isotopy, see Sonesson 2017.

Return to text

6. This fundamentally opposes Jean-Jacques Nattiez’s paradigmatic analysis ([1975] 1990), which focuses on the similarity of material in an essentially motivic manner.

Return to text

7. The distinction between open and closed isotopies is taken from Umberto Eco (1979, 33–34 and, more generally, [1962] 1989).

Return to text

8. Notably, within his theory of virtual agency, Robert Hatten defines an Actant as an unspecified source of energy without constructing a particular or individual agency (Hatten 2018, 31). Although neither an Actor (a role in the dramatic trajectory) or an Agent (with human characteristics), the Actant nevertheless contains meaning. My conception of the Actant level of a topic dovetails, as Almén’s work, with Hatten’s conception, with the lower levels effectively acting as a pre–Actant level.

Return to text

9. Watabe (2015, 2016) traces the increasingly common appearance of the Chorale in secular music across the nineteenth century, due to its association with certain Romantic ideals, while Narum (2013) identifies several prominent Chorales in the music of Schoenberg. More specifically, McKee 2007 traces the Sacred Hymn topic in Beethoven’s instrumental music, similarly providing an orbit of the topic’s characteristics.

Return to text

10. Ligeti [1992] 2007, 306. Schumann describes Stravinsky’s Chorale as a “creative” trope of the Hymn and Ombra topics. While there is little to distinguish the Hymn and Chorale topics, Schumann explains the Ombra infusion: as the “dissonant sonorities of the repeated opening chord (G major over a D-diminished triad) and frequent rests convey an unsettled expressive state connected to the ombra topic” (2021, 10). Schumann’s eighteenth-century subject position identifies these dissonances as transgressive to the archetypal tonal Chorale, whereas my predominantly post-tonal lens from a vantage point of Ligeti’s and Adès’s harmonic vocabulary frames Stravinsky’s triadic-rooted harmony as relatively consonant.

Return to text

11. Any significantly marked reversal of Actant-level characteristics may encourage a further expressive interpretation or point to a different topic. For example, the ff dynamics of Ex. 3 could be interpreted as a form of parody, if we understand parody as a marked manipulation of borrowed material (Everett 2009). Alternatively, this passage may evoke the tradition of loud instrumental hymns common in nineteenth-century music, which Hentschel and Kreutz (2021) term the Glorifying Hymnic. Sánchez-Kisielewska notes that these “often have a patriotic rather than religious connotation and flourish with the rise of nationalisms in nineteenth-century Europe” (2018, 127).

Return to text

12. Although I propose viewing this excerpt’s parallel voice-leading through the context of the Chorale topic’s ideal voice-leading, the ocarina’s timbre and parallelism may evoke a folk topos.

Return to text

13. Beyond this general association, composers’ own writings and interviews point to a variety of imagery. For example, Ligeti associated the Sound Mass with clouds, Xenakis with clouds and galaxies, Barry Truax with swarms and water. For a substantial discussion of the characteristics, associative metaphors, and their possible role in the perception of Sound Masses, see Douglas, Noble and McAdams Douglas, Noble, and McAdams 2016; Noble Noble 2018; Noble, Thoret, Henry and McAdams Noble et al. 2020.

Return to text

14. This characteristic directly reflects Douglas, Noble and McAdams (2016, 295): “an intermediate rating would represent situations in which some but not all of the sounds were integrated into a sound mass, or in which multiple simultaneous masses were perceived, or in which sounds were partially integrated but still retained distinct individual identities.”

Return to text

15. Elements of Ligeti’s conception of a close relationship between the Sound Mass and the Chorale are traceable in Ligeti’s sketches for the Hamburg Concerto; see Donaldson 2023b.

Return to text

16. Although not explicitly motivated by narrativity, Hepokoski and Darcy’s (2006) approach to sonata form analysis leans on a (sometimes topic-inflected) narrative language in a manner that similarly may permit a less overt reliance on the specifics of harmonic processes.

Return to text

17. For a detailed discussion of Adès and the sonata, see Venn 2021a. Gallon (2013) explores the Quintet’s complex temporalities and their relationship with sonata form.

Return to text

18. Stoecker’s tracing of aligned cycles in Adès’s “Chori” from Traced Overhead (2014) captures a similar rooting of the Chorale topic in the homophony of aligned cycles. The Chorale in this movement remains at the F level according to the hierarchy below, continually in an emergent state as, although it frequently satisfies the tertian voicings and three or more parts, the Actant-level characteristics of clear phrases at a medium tempo in a singable range with appropriate voice-leading are not present. As it is at a medium-low dynamic throughout (another A-level characteristic), the Actant level remains close. From a different perspective, I explore the role of aligned cycles as controlling harmony associated with various topics in Adès’s Living Toys in Donaldson 2022.

Return to text

19. The descending three chords which open the first movement of Beethoven’s “Les Adieux” op. 81a might suggest that contour is not a foundational characteristic of the Horn Call. As Caplin (2005, 122) notes, though, this descent in Beethoven’s example—a characteristic of cadential closure—brings “a distinct sense of dissonance” relative to prevailing convention. Indeed, as I suggest elsewhere (Donaldson 2021b), depending on the intertexts engaged—including the distorted horn call opening Ligeti’s own Horn Trio—the opening of Adès’s Quintet might be considered a double reversal of contour, reverting to the ascending Horn Call common in eighteenth-century music.

Return to text

20. One might question whether a loud dynamic is central to the Horn Call and therefore an E-level characteristic. After all, should a Horn Call not be clearly audible? Siegfried’s call, however, is at times piano. Combined with the limited analytical benefit of tracing “loudness” across a work as contributing to a Horn Call isotopy (compared with tracing prominent rising motions), a loud dynamic is of limited use at the E-level.

Return to text

21. Adès’s use of multiple simultaneous time signatures complicates bar numbering. For excerpts between the figures in Video Ex. 1/Ex. 10 (such as e3’s Fig. 2+7), I count the largest notated bar length as the unit of measurement.

Return to text

22. See Wörner (, 302) for a detailed discussion of the opening’s tonal implications.

Return to text

23. Note that the Exposition does not repeat to the beginning (and back to the A–level Horn Call) but only to e2, thereby skipping over a reprise of the clear Horn Call and keeping the Horn Call in a relatively emergent state after its opening clarity.

Return to text

24. Although I focus on the ascending Horn Call, repeated instances of its retrograde, i.e. descending horn fifths, occur. As these do not embody E-level characteristic and often occur close to their ascending version, they do not affect the isotopies outlined here.

Return to text

25. Stoecker (2014, 46) likewise calls this the secondary theme.

Return to text

Copyright Statement

Copyright © 2024 by the Society for Music Theory. All rights reserved.

[1] Copyrights for individual items published in Music Theory Online (MTO) are held by their authors. Items appearing in MTO may be saved and stored in electronic or paper form, and may be shared among individuals for purposes of scholarly research or discussion, but may not be republished in any form, electronic or print, without prior, written permission from the author(s), and advance notification of the editors of MTO.

[2] Any redistributed form of items published in MTO must include the following information in a form appropriate to the medium in which the items are to appear:

This item appeared in Music Theory Online in [VOLUME #, ISSUE #] on [DAY/MONTH/YEAR]. It was authored by [FULL NAME, EMAIL ADDRESS], with whose written permission it is reprinted here.

[3] Libraries may archive issues of MTO in electronic or paper form for public access so long as each issue is stored in its entirety, and no access fee is charged. Exceptions to these requirements must be approved in writing by the editors of MTO, who will act in accordance with the decisions of the Society for Music Theory.

This document and all portions thereof are protected by U.S. and international copyright laws. Material contained herein may be copied and/or distributed for research purposes only.

Prepared by Aidan Brych, Editorial Assistant

Number of visits:

6171