Mid-Exposition Modal Contrast and Francesco Galeazzi’s “Characteristic Passage”

Rebecca Long

KEYWORDS: form, Francesco Galeazzi, eighteenth century, early Classical, Luigi Boccherini, Domenico Scarlatti, Joseph Haydn, history of theory

ABSTRACT: This article considers the merits of analyzing a compositional practice that occurs in some major-mode, mid-eighteenth-century sonata-form works using contemporaneous concepts. In these works, the post-transition part of the exposition opens in the minor-mode version of the secondary key rather than the prepared, major-mode key. This minor-mode insertion is short-lived: the movement usually shifts to the anticipated, major-mode secondary key after a phrase or two, and the exposition concludes in that key. These passages are best understood as minor-mode examples of Francesco Galeazzi’s “characteristic passage,” a medial passage that occurs in the secondary key. While they can be analyzed using modern approaches to sonata form, these approaches often dramatize this point in the exposition in a way that is inconsistent with mid-eighteenth-century style. In addition to arguing for analysis informed by contemporaneous thought, this article includes an examination of the hallmarks and use of minor-mode characteristic passages, the use of these passages in minor-mode movements from the mid-eighteenth century and beyond, and a discussion of possible historical precedents. The article’s conclusion considers analyses of two works that, from a modern perspective, use the same structure but that, from Galeazzi’s perspective, are different in both structure and implication. This suggests that, much as conflicting analyses reveal different aspects of a single work, different apparatuses—be they contemporary or contemporaneous—may reveal different aspects of style.

DOI: 10.30535/mto.30.3.3

Copyright © 2024 Society for Music Theory

Introduction

[0.1] In the introduction to Journeys through Galant Expositions, Poundie Burstein wryly observed that “almost every discussion of musical form begins with a warning to avoid shoving music into prefabricated, formal ‘jelly-moulds.’ Inevitably, this is followed by proposing a new jelly-mould into which to shove the music” (Burstein 2020, 4). The present article, for better or worse, upholds this tradition with one notable exception. I do not propose a new jelly-mold here; I revive an old one.

[0.2] This article considers some eighteenth-century expositions wherein a passage in the secondary key’s parallel minor highlights the secondary key’s arrival. These minor-mode passages frequently coincide with what one could analyze as the beginning of the secondary or subordinate theme using current analytical approaches to sonata form such as Hepokoski-Darcian Sonata Theory or Caplinian formal-function theory (Hepokoski and Darcy 2006; Caplin 1998). However, these approaches tend to dramatize this point in the exposition in a way inconsistent with the mid-eighteenth-century style. I argue that these passages can be fruitfully understood as examples of Francesco Galeazzi’s “characteristic passage,” defined as an optional passage that “is introduced for greater charm” and represents a point of merely local contrast within the larger motion to the secondary key (Galeazzi [1796] 2012, 328, emphasis mine).(1) Analysis through Galeazzi’s eighteenth-century lens allows us to better understand how these passages work within their respective movements and the style at large.

[0.3] Several recent volumes show that analysis of eighteenth-century sonata forms or sonata-form structures such as expositions benefit from a flexible approach that takes contemporaneous discussions and practices into account. Robert Gjerdingen’s Music in the Galant Style (2007) considers galant-era works through contemporaneous schemata. Burstein’s Journeys reconsiders Heinrich Christoph Koch’s understanding of form-as-journey, as opposed to form-as-container. Finally, Yoel Greenberg’s How Sonata Forms (2022) examines aspects of sonata form in a new light, using an approach borrowed from evolutionary theory to better understand how the form developed across the eighteenth century. In proposing Galeazzi’s ideas as an analytical tool, I hope to add to this conversation and suggest that using contemporaneous tools in analysis can provide a different, enlightening perspective.

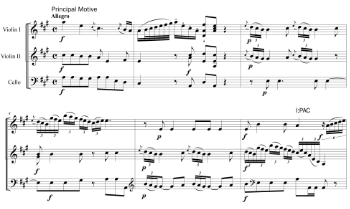

Example 1. Luigi Boccherini, String Trio in A Major, G. 79, ii, exposition

(click to enlarge, see the rest, and listen)

[0.4] Example 1 shows the exposition from the second movement of Luigi Boccherini’s String Trio in A Major, G. 79 (1760). This example includes an intermediary passage that unexpectedly shifts to the minor dominant instead of the typical major dominant. The minor-mode insertion is short-lived. The work shifts to the major-mode secondary key after a single phrase (at m. 18), and the exposition concludes in that key. This passage is not difficult to explain using current approaches: one might identify it as the first part of a two-part subordinate theme, as part of a trimodular block, or simply as a minor-mode beginning of the secondary or subordinate theme.(2)

[0.5] If current approaches provide analytical options, why reanimate a 200-year-old approach to the exposition? By using a given analytical apparatus or term, we implicitly place the music under analysis into a group. In choosing to analyze the String Trio’s passage as an example of Sonata Theory’s trimodular block, we group that work with other examples of the trimodular block such as the first movements of Franz Schubert’s String Quartet No. 14 in D Minor, D. 810, “Death and the Maiden” (1824); Ludwig van Beethoven’s Piano Sonata in F Major, op. 10, no. 2 (1796–7); and Beethoven’s Piano Sonata in C Major, op. 2, no. 3 (1794–5). We might even recognize a closer relationship between the String Trio and the last of these works, as both initiate their secondary key areas with passages in the “wrong” minor mode.(3) But neither Sonata Theory nor form-function theory were created with mid-eighteenth-century music and style in mind. Both James Hepokoski and Warren Darcy’s Elements of Sonata Theory: Norms, Types, and Deformations in the Late-Eighteenth-Century Sonata and William Caplin’s Classical Form: A Theory of Formal Functions for the Instrumental Music of Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven delineate the scope of their studies in their titles. Justin London notes that despite the deceptively large number of examples, neither work “broadly sample[s] the music of the common practice period, nor even the more specialized sub-periods and genres that are the focus of their studies” (2022, 2.5). This disconnect causes issues when analyzing mid-eighteenth-century music. The various adjustments and efforts needed to adapt an analytical apparatus built for (and from) late-eighteenth-century music to mid-eighteenth-century works create a false perception that the analysis of mid-eighteenth-century music is complicated. The problems are similar to using a flat-head screwdriver on a Phillips-head screw. The flat-head screwdriver can get the job done, but it isn’t the best option since it requires more effort and can damage the screw head (or our perceptions of a style).

[0.6] I begin with an overview of the exposition as described in Galeazzi’s work, using his sample Allegro movement. A more complete discussion of the minor-mode characteristic passage from Boccherini’s String Trio, G. 79 follows. Stepping backward in time, “Possible Historical Precedents” looks at some plausible roots of the minor-mode characteristic passage’s use. In the section entitled “Mid-Eighteenth-Century Practice,” I provide the reader with a list of selected movements that include these passages along with some limitations of the current study. I then consider close analyses of four normative examples. “Interpretation and Meaning” uses the expressive model of the da capo aria as a framework for considering the possible interpretations and emotional implications of minor-mode characteristic passages. In “Minor-Mode Movements and Later Vestiges,” an examination of the (rare) appearance of these passages in mid-eighteenth-century minor-mode movements leads to a consideration of late-eighteenth- and nineteenth-century uses of similar passages. These examples revive the issue of period-appropriate analysis, which leads to my conclusion in which I consider what the lens of the late-eighteenth-century clarifies and obscures in terms of our analyses of music from earlier decades.

1. Galeazzi’s Exposition

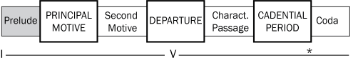

Example 2. Francesco Galeazzi’s sample Allegro

(click to enlarge)

Example 3. Diagram of Galeazzi’s exposition

(click to enlarge)

Example 4. List of Galeazzi’s exposition terminology

(click to enlarge)

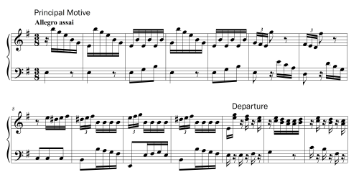

[1.1] Published in 1796, Books 3 and 4 of Galeazzi’s Elementi teorico-pratici di musica provide an introductory course in composition.(4) Galeazzi uses his own Allegro as the sole example of sonata form within the work. In addition, he points readers to two contemporary composers, Boccherini and Joseph Haydn. As we shall see, the Allegro exemplifies the mid-eighteenth-century Italianate style.(5) Example 2 shows Galeazzi’s Allegro.(6) The chart in Example 3 provides an outline of the exposition using Galeazzi’s terminology. Here, the required sections of Galeazzi’s exposition appear in large boxes while optional, additional sections appear in smaller boxes. The prelude is shown in gray, as it does not occur in Galeazzi’s example. The tonal motion of the exposition appears below the sections. An asterisk marks the point at the end of the cadential period where an authentic cadence in the dominant occurs. Example 4 provides a list of Galeazzi’s terminology. There are similarities between some sections of Galeazzi’s exposition and sections common to modern discussions of the exposition. We may be tempted to re-evaluate Galeazzi’s ideas in modern terms (e.g., “the characteristic passage is the beginning of the subordinate theme”). But there is no one-to-one correspondence here. The points of contact between these accounts of form are not fixed, but fluid. Several parts of Galeazzi’s account can feasibly map onto more than one section of the modern conception of the exposition, and some optional parts will not occur in all examples. At best, we can create cautious associations between Galeazzi’s account and modern ideas, such as: the characteristic passage, when present, frequently coincides with the beginning of the second or subordinate theme but does not have the same function or dramatic implications as that section. While I discuss the relationship between the minor-mode characteristic passage and several ideas from modern theory below, the remainder of my work avoids invoking modern terminology in order to avoid any preconceived notions, implications, or connotations thereof.

[1.2] Although my focus in this article is the characteristic passage, I will provide a brief overview of the exposition, as many will be unfamiliar with Galeazzi’s work.(7) The principal motive occurs in mm. 1–9 in Example 2. Galeazzi compares this section to the subject of a fugue or “the theme . . . of the musical discourse.” The second motive, which Galeazzi compares to the countersubject of the fugue, begins in m. 10. For Galeazzi, this section is “effectively tied together with the [principal motive].” The departure to closely related keys (hereafter “departure”) occurs after the second motive and concludes at m. 16. This section modulates to the dominant and “terminates in the fifth of the key in which one currently is” (Galeazzi [1796] 2012, 326–28). While the second motive and departure are treated separately in Galeazzi’s prose, he does not specify where the second motive ends and the departure begins in his Allegro. Burstein, however, argues that the second motive occurs in mm. 10–13 and the departure in mm. 14–16. In his view, “the secondo Motivo [second motive] serves as a sentential presentation and the Uscita [departure] as a sentential continuation” (Burstein 2020, 92).

[1.3] The characteristic passage, the focus of this article, occurs in mm. 17–20. Galeazzi describes this optional passage as “a new idea that is introduced for greater charm about halfway through the [exposition] . . . it must be gentle, expressive, and tender” (Galeazzi [1796] 2012, 326–28). The characteristic passage occurs in the secondary key, but its arrival is not the goal of the departure that precedes it (if it were, this arrival would not be optional). Rather it is the cadential period—the final required section of the exposition, which occurs immediately after the characteristic passage—that is the goal of the tonal motion in the departure. The characteristic passage merely decorates a space between these sections. Burstein suggests that “using the terminology of [Joseph] Riepel and Koch, the Passo di mezzo [characteristic passage] could be understood as an Einschiebsel or eingeschobener Satz . . . a type of parenthetic aside within an encompassing tonal drive toward the cadence” (Burstein 2020, 95).(8)

[1.4] Despite descriptions of the characteristic passage as “optional,” “decorative,” or “parenthetical,” I think most readers of this article—the majority of whom are likely to understand sonata form through modern models of the form—will find it most natural for the characteristic passage to somehow act as a beginning. If not the beginning of a secondary or subordinate theme, must it not at least be the beginning of the second part of the exposition? Burstein argues that, as in modern conceptions of sonata form, Galeazzi divides the exposition into two parts, but this division occurs at a different point. Modern conceptions bifurcate the exposition between the transition and secondary theme; Galeazzi divides his immediately following the principal motive. This division places the principal motive against the motion away from that key and confirmation of the secondary key. This “suggests that it is the transitional secondo Motivo [second motive] . . . that serves as the primary dialectical counterweight to the main theme” because it “initiates the large motion towards the formal cadences . . . in the secondary key” (Burstein 2020, 94). Galeazzi’s description of the second motive, in which he casts that section as a countersubject to the principal motive, supports this reading. In this view, the characteristic passage occurs in the middle of the second part of the exposition, not the middle of the exposition as a whole. Burstein notes that Galeazzi’s designation of the characteristic passage as optional may seem confusing to the modern reader, because current terminology and conceptions of sonata form typically construe the opening of the secondary theme (which the characteristic passage, when present, frequently corresponds to) as the aim of the transition and the foil to the primary theme. This was not the case for Galeazzi, nor for other eighteenth-century theorists. Jane R. Stevens argues that eighteenth-century theorists “did accurately perceive large-scale harmonic structure . . . but themes other than the [principal theme] seem to have been seen chiefly as a source of musical effect . . . achieved on an immediate level” (1983, 304).(9)

[1.5] The characteristic passage in the sample Allegro provides clues about its normal use. It consists of a repeated two-bar idea, just as the second motive did.(10) Galeazzi does not specify any sort of ending for this section—the next section, the cadential period, begins after the characteristic passage finishes its melodic repetition. This final required section of the exposition, should be “a display of brio and bravura” if a characteristic passage occurred. The cadential period ends with a final cadence in the secondary key, which in Galeazzi’s example occurs in mm. 21–24. A coda, here found in mm. 24–28, may follow.

[1.6] Other eighteenth-century authors pointed out passages analogous to Galeazzi’s characteristic passage. As reported in Stevens (1983, 301–3), Koch mentions a cantabile phrase that occurs after the half cadence in the dominant in major-mode expositions(11) and Riepel mentions a similarly placed passage in the first movement of a symphony. However, both authors discuss these briefly, in passing. Galeazzi, on the other hand, emphasizes thematic character in his description of the exposition more than other contemporaneous authors and balances this with an eighteenth-century focus on tonal trajectory. He designates those sections that do the tonal work of the exposition—establishing the home key (principal motive), moving away from that key (departure), and confirming the secondary key (cadential period)—as the three required portions of the exposition. All other sections, including the characteristic passage, are optional. That said, Galeazzi’s detailed descriptions of these optional sections encourage his reader (the amateur composer) to use them by suggesting possibilities for artistic expression.

[1.7] Still, it is tempting to understand Galeazzi’s descriptions of the character and musical hallmarks of the exposition’s sections as presaging modern ideas in a similar vein (e.g., Hepokoski and Darcy’s “energy increase” during the transition). While Galeazzi does seem to be one of the first to take up these concerns, we have to keep in mind that he wrote these descriptions not so that a twenty-first-century analyst could better understand the music of the eighteenth century, but for an eighteenth-century amateur musician. Galeazzi is not constructing an analytical method (though we may appropriate it as such).(12) Rather, like other authors of contemporaneous pedagogical texts, he is trying to preempt natural questions that arise from students writing their first works: What sort of melody should I write for the cadential period? (Answer: A display of brio and bravura that shows off the performer’s agility.) How do I come up with this much musical material? (Answer: Steal from yourself.) How elaborate should the principal motive be? (Answer: Keep it simple.) Galeazzi’s ideas are derived from contemporaneous practice, which make his work informative regarding that practice, but the purpose of the text is first and foremost practical.

2. Boccherini, String Trio in A Major, G. 79, 2nd movement

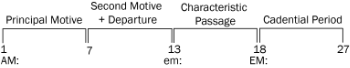

Example 5. Boccherini, G. 79, ii, exposition diagram

(click to enlarge)

[2.1] Let us look again at the second movement of Boccherini’s String Trio, G. 79 (see Example 1 above). Example 5 provides a diagram of the exposition using Galeazzi’s terminology. The work opens with a six-bar principal motive that concludes with the tonic.(13) Galeazzi’s description of sonata form suggests using material from the principal motive for both the departure and the cadential period. For shared material, Boccherini’s movement reuses a sixteenth-note triplet figure first found in mm. 3 and 5. This figure later appears during the departure (m. 12) and in the cadential period (m. 17). The second motive and departure occur in mm. 7–13, with the former flowing seamlessly into the latter. As in Galeazzi’s Allegro, the second motive here consists of a repeated idea (here a one-bar idea) while the departure continues to a conclusion on the dominant of the secondary key (V/V). The characteristic passage follows in mm. 13–18. Instead of occurring in E major, the major dominant, as would be usual at this point, the passage occurs in E minor. After three iterations of an initial two-bar canonic statement in the violins, mm. 16–17 of the passage push towards a conclusion on the dominant (V/v) at the beginning of m. 18.(14) This allows for a quick move to E major for the cadential period that occurs in mm. 18–24. The cadential period begins with the return of the triplet figure from the principal motive and concludes with the tonic of the secondary key in m. 24. A brief coda completes the exposition.

[2.2] As noted in the introduction, the characteristic passage could easily be interpreted in modern terms as part of a trimodular block from Sonata Theory, as the first part of a two-part subordinate theme using form-function theory, or as a minor-mode beginning to a secondary or subordinate theme (Hepokoski and Darcy 2006, 172–75; Caplin 1998, 117).(15) These are all viable analyses of Boccherini’s exposition. The problem lies in the late-eighteenth-century analytical baggage that these interpretations bring to the table.(16)

[2.3] Difficulties can arise when there is a mismatch between a given piece’s time period and the period for which an analytical apparatus was constructed. For example, both Sonata Theory and form-function theory place significant interpretive weight on cadential articulation, reflecting the music they use as their basis. This creates a problem when analyzing music from earlier in the eighteenth century. Analysis with Sonata Theory or form-function theory suggests that the String Trio is paradigmatic by virtue of its alignment with a known structure (be it a two-part subordinate theme or a trimodular block), when in fact the opposite is true. Though cadential articulation between all sections of an exposition may be the norm in the late eighteenth century, it is not the norm in early- and mid-century works. Compared with other movements from the same period, Boccherini’s inclusion of a half cadence dividing the secondary key area into two parts is less normative than these interpretations would suggest—indeed, it is a notable feature that a historically informed reading can elucidate. Galeazzi’s account includes cadences at the conclusion of the three required sections of the exposition: the principal motive (optional cadence), the departure, and the cadential period, but provides no specific commentary on the conclusions of the remaining sections, the second motive and characteristic passage.(17) In most of the movements examined here, the characteristic passage ends without a cadence, as in Galeazzi’s Allegro.

[2.4] A second issue arises when we consider how the minor-mode passage fits in with the rest of the exposition. Many modern approaches tend to understand the exposition as a single, long-range dramatic arc that casts the tonic and secondary keys as opposing forces. Caplin calls this the “tonal-polarity model.”(18) The tonal-polarity model imbues the beginning of the subordinate or secondary theme with a hefty dramatic weight not found in eighteenth-century descriptions of the exposition, including Galeazzi’s. This is evident in Hepokoski and Darcy’s descriptions of both the trimodular block and minor-mode onsets of the secondary theme. The authors characterize the appearance of the minor mode in Beethoven’s op. 2, no. 3, one of the trimodular block examples cited in my introduction, as “expressively ‘flawed’ . . . the dominant key having unexpected collapsed into minor (‘lights out’) at this point. This ‘flaw,’ it seems, will have to be expunged” (Hepokoski and Darcy 2006, 172). Their discussion of minor-mode beginnings to the secondary theme also suggests a theatrical drama: “Sometimes the first [secondary theme-] module within a major-mode work makes its appearance in the minor dominant (v) with the implication of tragedy, malevolence, a sudden expressive reversal, or an unexpected complication within the musical plot” (Hepokoski and Darcy 2006, 141).

[2.5] While the structural aspects of Boccherini’s passage may be similar to a trimodular block (or a minor-mode beginning to the secondary theme), the dramatic connotations these terms carry are inappropriate to the mid-eighteenth century. Galant works “provided opportunities for acts of judging, for the making of distinctions, and for the public exercise of discernment and taste” (Gjerdingen 2007, 4). Stevens notes that composers and authors from this period focus on the idea of contrast as a central element in music instead of global dramatic trajectories. Contrast occurs at a local level and not “as the result of long-range operations” (1983, 288). Concerns with large-scale dramatic arcs are also not evident in the work of other contemporaneous authors: “even when they point out conventions of style . . . theorists seem to understand [such contrast] only in terms of immediately surrounding events, not in relationship to events widely separated in time” (304).

[2.6] While the shift to minor certainly is not normative, the implications of this shift are quite different in Galeazzi’s account than in either modern or other contemporaneous approaches. The shift to minor mode here may be readily explained as a more emphatic (or perhaps extreme) way of creating contrast between the characteristic passage and the cadential period. Ethan Haimo discusses accounts of mode from the second half of the eighteenth century and notes that by that time the major and minor modes were “palpably different in kind and affect

3. Possible Historical Precedents

[3.1] What are the historical origins of the minor-mode characteristic passage? My preliminary work in this area suggests late seventeenth- and early-eighteenth-century Italian practice as a potential antecedent. Many of the composers discussed below are connected to Italian practice in some way, and future investigations might begin with a closer examination of the Italian style. The use of the minor key as a contrasting element has precedents in high Baroque (Italian) compositional practice. Bella Brover-Lubovsky (2003) has examined the use of the parallel minor, especially the minor dominant, in Antonio Vivaldi’s works. She suggests that Vivaldi experimented with ways of creating tonal and modal contrast, including using the minor dominant where the major dominant would be expected. Brover-Lubovsky notes that “whereas lowering the third of the tonic triad is rare in [seventeenth-century] music, lowering [the third] of the dominant triad (when used as the tonic chord in the key of the dominant) is an established feature” (107). She points to a potential precedent in the “Mixolydian dominant,” a conceptualization wherein certain keys were linked to the Mixolydian rather than the Ionian mode. In a separate article, Brover-Lubovsky connects Vivaldi’s compositional practices to the emerging concept of modal dualism, arguing that “musical practice itself legitimized the variety of options available [for approaching major-minor tonality]” in the early-eighteenth century (2004, 82).

[3.2] The compositional practices of early-eighteenth-century composers form an important element for consideration. In an article discussing the music of Domenico Scarlatti, Michael Talbot (1985) provides an overview of the use of modal shifts in the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries. Talbot points out that in the 1710s, “Italians began to introduce short minor-key passages as ‘pathetic’ enclaves within a section in the parallel major key” (31). These form a precedent to Scarlatti’s use of modal shifts, including minor-mode characteristic passages. While Scarlatti uses modal shifts at various points during his expositions, Talbot notes that “a shift to the minor often introduces or follows immediately after the hiatus commonly separating the first subject or its appended bridge passage and the second subject; modal opposition helps to dramatize this important point of articulation” (Talbot 1985, 38). As Scarlatti’s works include some of the earliest uses of minor-mode characteristic passages I have documented, the historical precedents Talbot mentions for Scarlatti’s music likely extend to other, later composers as well.

[3.3] That said, the amount of influence exerted by these precedents and early adopters, like Scarlatti and Carlos Seixas, is unclear.(20) It is possible that no single-point stylistic origin for this practice exists for all composers. Some composers may have adopted the shift to minor mode because of the influence of the Italianate style.(21) This seems especially true for composers like Boccherini and Haydn who, as we shall see below, used the minor-mode characteristic passage in multiple works and were well-versed in the Italianate style. Others, however, when facing the problem of creating local contrast, may have simply understood the minor mode as a workable solution.

4. Mid-Eighteenth-Century Practice

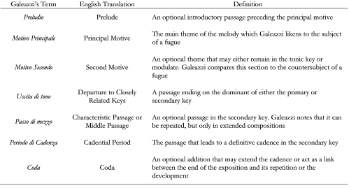

Example 6. Selected movements with minor-mode characteristic passages

(click to enlarge)

[4.1] Analyzing the exposition using Galeazzi’s terminology groups Boccherini’s String Trio with those works shown in Example 6, which contains a selected list of mid-eighteenth-century chamber works containing minor-mode characteristic passages. My study focuses on chamber music, though undoubtedly examples exist in other repertoires. The heyday of this practice was the mid-eighteenth century, particularly the 1750s and 1760s. The earliest use I have found occurs in the works of Scarlatti and Seixas. These pieces cannot be precisely dated but were written in the first half of the century. The use of a minor-mode characteristic passage does not appear to be a particularly common compositional choice, but it does occur in broad range of composers.

[4.2] The vast majority of works in Example 6 occur in major keys. The lone exception, Seixas’s Keyboard Sonata in E Minor, presents a rare case of a minor-mode characteristic passage (using ♭iii) appearing alongside a minor-mode tonic key. This movement is considered in a separate section below. The movements listed are all performed at faster tempos, but this correlation says less about tempo and more about the (usually) greater length of faster movements when compared with slower movements at this time. The optional characteristic passages are more likely to occur in longer movements.

[4.3] The effect of the minor-mode characteristic passage may be most potent when the minor mode appears only during that portion of the exposition. However, some of the movements listed in Example 6 contain brief jaunts to the minor mode before or after the characteristic passage.(22) For example, Gaetano Pugnani’s Trio Sonata in C Major includes a brief foray into the minor mode during the departure in mm. 16–18. Scarlatti’s Keyboard Sonata K. 473, on the other hand, contains a small aftershock of the minor mode during its cadential period in mm. 33–34. In both these movements, the characteristic passage retains its modal contrast with its immediate surroundings, but the presence of the minor mode is no longer unique to the characteristic passage.(23) While neither Pugnani’s Trio nor Scarlatti’s Sonata directly juxtapose the minor-mode characteristic passage with other minor-mode material at the conclusion of the departure or the beginning of the cadential period, the use of minor-mode material elsewhere in the exposition makes the minor mode’s use in the characteristic passage less marked in the context of the exposition.

5. Structure and Organization

[5.1] The characteristic passage from Galeazzi’s Allegro consists of a repeated two-bar idea. In most works listed in Example 6, the characteristic passage occurs or at least begins similarly to Galeazzi’s example, though the length of the idea, number of repetitions, and whether the characteristic passage includes other material remain flexible. Minor-mode characteristic passages overwhelmingly conclude with the secondary key’s dominant, which facilitates a shift to the major mode. The strength of these conclusions varies. In many cases, nothing within the characteristic passage itself signals the impending conclusion. As in the characteristic passage in Galeazzi’s Allegro, the beginning of the cadential period signals the end of the characteristic passage (see the examples by Scarlatti and Georg Benda below). Other passages feature a brief pause between the characteristic passage and the cadential period in the form of a rest or held note (see the examples by Haydn and Seixas below). Using a clear cadence to conclude a minor-mode characteristic passage is less common. Boccherini’s G. 79 (see Example 1) is an exception in this respect. Indeed, Boccherini’s works are notable among the examples listed in Example 6 for using a clearer concluding cadence at the end of the characteristic passage.(24)

[5.2] The next four examples show expositions by Scarlatti, Haydn, Benda, and Seixas that contain characteristic passages. These provide a general idea of the variety of strategies used in the movements listed in Example 6. The paragraphs below examine each example in turn, focusing primarily on the harmonic and formal characteristics of these passages. A further section below considers their interpretation and meaning.

Example 7. Domenico Scarlatti, Keyboard Sonata in B-Flat Major, K. 473, exposition

(click to enlarge, see the rest, and listen)

[5.3] Example 7 comes from Scarlatti’s Keyboard Sonata in B-flat Major, K. 473. The principal motive introduces a figure in m. 4 that can be understood as the primary source of the exposition’s remaining material. Compare this example to similar material from the second motive (mm. 9–10 and 15–17), the departure (mm. 19–20), the characteristic passage (mm. 24–26), and the cadential period (mm. 28–29). The only portion of the exposition untouched by this material or its variants is the coda (mm. 48–54).

[5.4] The characteristic passage, mm. 24–28, comprises a two-bar idea and its repetition, similar to the characteristic passage from Galeazzi’s Allegro. The harmonic progression here is simple and repetitive. The repeated idea moves from the tonic to the dominant each time it occurs. The bass part moves sequentially from F, to G, to

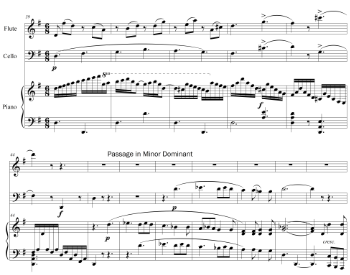

Example 8. Example 8. Joseph Haydn, String Quartet in E-Flat Major, op. 1, no. 2, v, exposition

(click to enlarge, see the rest, and listen)

[5.5] The finale of Haydn’s String Quartet in E-flat Major, op. 1, no. 2, shown in Example 8, also contains significant melodic repetition. Here, multiple elements create the strong sense of contrast that occurs between the characteristic passage and the sections that surround it. The shift to the minor mode is combined with changes to melodic material, dynamics, and orchestration to create a greater impact than the change in mode would on its own. The characteristic passage, mm. 16–22, features a two-measure idea that occurs three times in total (statement plus two repetitions). The passage’s melodic material—a four-note, syncopated, lamenting descent in thirds—represents a dramatic shift away from the material heard in previous sections. The principal motive, departure, and cadential period share an emphasis on arpeggiations performed in eighth notes. Furthermore, the departure and cadential period overlap to an extent in material. Compare mm. 13–16 of the departure (bracketed in the example) to the cadential period in mm. 23–28. The latter feels like a variation and extension of the former. The similarity between the departure and cadential period, which surround the characteristic passage, augments that section’s ability to create striking local contrast.

[5.6] The characteristic passage also features changes in dynamics and orchestration. The passage, marked piano, is the only portion of the exposition not performed at forte. And in the principal motive, departure, and cadential period, the first violin dominates the ensemble as the primary melodic voice, with the other instruments frequently playing supporting roles, often in rhythmic unison. At times, the full ensemble plays in melodic and rhythmic unison, as in mm. 3, 15–16, and 25–28. In the characteristic passage, the second violin and viola perform the main melodic material, the first violin provides a repetitive stream of sixteenth notes on F, and the cello performs quarter notes on the beat that accentuate the melody’s syncopation. The passage comes to a halt at m. 22, where a brief rest precedes the onset of the cadential period.

Example 9. Georg Benda, Sonata no. 10 in C Major, iii, exposition

(click to enlarge, see the rest, and listen)

[5.7] Example 9 provides the exposition to the third movement of Benda’s Keyboard Sonata no. 10 in C Major. The principal motive (mm. 1–10), departure (11–18), cadential period (mm. 27–41) and coda (mm. 41–48) are each unique in their material but use similar rhythms, relying primarily on near-continuous groups of eighth notes in the work’s

[5.8] This melody touches on the most prominent tones of the minor dominant key, G minor. The statement (m. 19) begins with a held D in the right hand, harmonized by an inverted minor tonic in the left hand; the sixteenth-note descent passes through the lowered third,

Example 10. Carlos Seixas, Keyboard Sonata no. 10 in C Major, exposition

(click to enlarge, see the rest, and listen)

[5.9] So far, the characteristic passages we’ve examined in this section have consisted of a brief, two- to four-bar statement and its repetition(s). The first movement of Seixas’s Keyboard Sonata no. 10 in E Major, shown in Example 10, provides an example of a characteristic passage that begins with a statement and repetition, but then continues to different material. The characteristic passage occurs in mm. 12–19 in B minor, the minor dominant. At m. 20 the cadential period begins with a prolongation of B major, the major dominant. The characteristic passage begins with a repeated two-bar idea in mm. 12–13 and 14–15 whose melody outlines the minor third B–D, emphasizing the shift to the minor dominant. It then continues to a prolongation of the (local) dominant,

[5.10] If one’s analytical intuitions are grounded in late-eighteenth-century Classical music, then it is entirely reasonable to predict a sentential structure for the characteristic passage from the description thus far. This turns out not to be the case here. The characteristic passage effectively ends at m. 19, but we only recognize this ending because of the onset of the cadential period (and the arrival of the major tonic) at m. 20. The boundary between characteristic passage and cadential period is once again created by change in mode and material, but not by cadence—even though a sentential preparation appears to occur. Indeed, Seixas’s characteristic passage eschews the (implied or actual) resting point that occurs in the other works discussed thus far. While dominant-to-tonic motion occurs at the boundary point, it is merely local-level harmonic motion. The main signal of the cadential period’s onset occurs in the right hand’s change in register as well as the ostentatious sixteenth-note arpeggios at m. 21. The key-confirming, cadential period–ending authentic cadence occurs soon after, at m. 26, and is followed by a brief coda.

6. Interpretation and Meaning

[6.1] Although different in terms of form, the minor-mode characteristic passage plays an expressive role similar to that of a da capo aria’s central section. Paul Sherrill has argued that da capo arias “either [present] two emotions in stark contrast or two perspectives on one dominant feeling” (2016, 12). A similar set of options seems to exist for the minor-mode characteristic passage: the shift to the minor mode coincides with a similar, equally temporary change in emotions, but the gravity or magnitude of that change results from a combination of factors, not merely the change in key.

[6.2] Let’s reconsider the emotional trajectory and potential meaning behind two of the examples above. The characteristic passage in Haydn’s String Quartet (Example 8) might be understood as a momentary lament because of its descending, repetitive scalar melody. The sharp contrast between the melodic content of the characteristic passage and the more jocular, lively material from the principal motive, departure, and cadential period heightens the emotional impact of the former. Compare this to the characteristic passage from Scarlatti’s Keyboard Sonata (Example 7). The shared material between all sections of the exposition except the coda, seems to indicate an emotional shift of lesser magnitude. The motion to minor still carries an impact, but melodically, the piece continues much in the same way as before. Instead of swinging from joy to lament, the Keyboard Sonata quietly shifts between two more closely related emotions, perhaps excitement and anxiety—although admittedly, the emotional direction these expositions take is less defined than in their operatic counterparts.(25)

7. Minor-Mode Movements and Later Vestiges

Example 11. Seixas, Keyboard Sonata in E Minor, exposition

(click to enlarge, see the rest, and listen)

[7.1] Minor-mode characteristic passages in minor-mode movements are exceptionally rare. Such expositions begin in the minor tonic (i), use the minor mediant (

Example 12. Ludwig van Beethoven, Piano Sonata in C Minor, op. 13, i, exposition, mm. 42–94

(click to enlarge, see the rest, and listen)

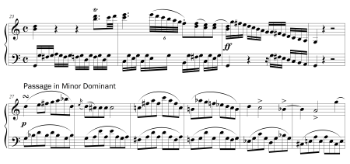

Example 13. Louise Farrenc, Trio for Piano, Flute, and Cello, op. 45, i, exposition, mm. 39–59

(click to enlarge, see the rest, and listen)

[7.2] In later works, the use of the mediant’s parallel minor (

[7.3] In my introduction, I discussed how linking Boccherini’s String Trio G. 79 with works featuring a trimodular block inherently, and anachronistically, attached Boccherini’s work to late-eighteenth-century formal ideas. Linking Beethoven’s Sonata and Farrenc’s Trio with Galeazzi’s ideas attaches these later pieces to a mid-eighteenth-century emphasis on local contrast inappropriate to their time of composition. However, the situation at hand is slightly different. Both Beethoven and Farrenc were likely aware of some of the works discussed above. It would be surprising if Beethoven, a student of Haydn, were unaware of the works by that composer listed here. Farrenc, meanwhile, edited the 22-volume work Le Trésor des pianistes along with her husband Aristide, which included several of the works listed in Example 6 as well as Beethoven’s op. 13.(26) It is possible that the influence of mid-eighteenth-century practice was among the reasons Beethoven and Farrenc used their minor-mode passages where they did.

Conclusion

Example 14. Beethoven, Piano Sonata in C Major, op. 2, no. 3, i, exposition, mm. 23–47

(click to enlarge, see the rest, and listen)

[8.1] Although one can interpret minor-mode characteristic passages using modern conceptions of sonata form, adopting Galeazzi’s contemporaneous approach provides insight into their function within the exposition. Earlier in this article, I briefly examined several possible interpretations of Boccherini’s String Trio, G. 79 using modern terminology. In that discussion, I drew a link between the String Trio and the first movement of Beethoven’s Piano Sonata in C Major, op. 2, no. 3 (composed in 1794–95), one of Hepokoski and Darcy’s primary examples of the trimodular block. Burstein (2021) discusses a Galeazzian interpretation of the Piano Sonata that provides a final demonstration of the various interactions between Galeazzi’s conception of sonata form and modern interpretations.(27) A minor-mode passage occurs in mm. 27–45 of the Piano Sonata, following a half cadence in tonic at m. 26 (see Example 14). Like the examples above, this passage represents the only use of the minor mode in the exposition and, like the String Trio, ends with a half cadence to facilitate the shift to the major mode. The passage is not, however, a minor-mode characteristic passage (or a descendant thereof). As Burstein argues, the passage is best understood as a second motive that occurs in the minor dominant.(28) Burstein understands mm. 1–26 as the principal motive and mm. 27–46 as the second motive that leads seamlessly into the departure (similar to what occurs in Galeazzi’s sample movement). Measures 47–77 form the characteristic passage and cadential period; a coda concludes the exposition in mm. 77–90.

[8.2] Taken together, my analyses of minor-mode characteristic passages and Burstein’s analysis of the minor-mode second motive in Beethoven’s Piano Sonata raise several questions regarding the analysis of eighteenth-century works. To modern listeners and analysts, the minor-mode passages in Beethoven’s Piano Sonata and Boccherini’s String Trio may seem like two instances of the same phenomenon: a secondary theme (subordinate theme, trimodular block) that unexpectedly begins in the minor mode. But when comparing these movements through the lens of Galeazzi’s ideas, we see the passages are quite different in function: Beethoven’s acts as a foil or countersubject to the principal motive, while Boccherini’s creates local contrast following the departure. This suggests that certain nuances of the eighteenth-century style may not be immediately apparent, depending on one’s analytical apparatus and its epistemological foundations. Much as conflicting analyses reveal various aspects of a single work, different apparatuses—be they contemporary or contemporaneous—may reveal distinctive aspects of style.

Rebecca Long

University of Louisville School of Music

Louisville, KY 40292

Rebecca.Long@louisville.edu

Works Cited

Brover-Lubovsky, Bella. 2003. “‘Die Schwarze Gredel,’ or the Parallel Minor Key in Vivaldi’s Instrumental Music.” Studi Vivaldiani: Rivista Annuale Dell’Istituto Antonio Vivaldi Della Fondazione Giorgio Cini 3: 105–32.

—————. 2004. “When the Dominant Doesn’t Dominate: Tonal Structures in Vivaldi’s Concertos.” Ad Parnassum: A Journal of Eighteenth- and Nineteenth-Century Instrumental Music 2 (4): 131–51.

Burstein, L. Poundie. 2020. Journeys Through Galant Expositions. Oxford University Press.

—————. 2021. “The Many Themes of Beethoven’s Op. 2, No. 3, and Their Stylistic Context.” Res Musica 13: 23–44.

Caplin, William E. 1998. Classical Form: A Theory of Formal Functions for the Instrumental Music of Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven. Oxford University Press.

Churgin, Bathia. 1968. “Francesco Galeazzi’s Description (1796) of Sonata Form.” Journal of the American Musicological Society 21 (2): 181–99.

Feder, Georg and James Webster. 2024. “Haydn, (Franz) Joseph.” Grove Music Online.

Galeazzi, Francesco. (1796) 2012. Theoretical-Practical Elements of Music, Parts III and IV. Translated by Deborah Burton and Gregory W. Harwood. University of Illinois Press.

Gjerdingen, Robert O. 2007. Music in the Galant Style. Oxford University Press.

Greenberg, Yoel. 2022. How Sonata Forms: A Bottom-Up Approach to Musical Form. Oxford University Press.

Haimo, Ethan. 2005. “Parallel Minor as a Destabilizing Force in the Abstract Music of Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven.” Tijdschrift Voor Muziektheorie 10 (2): 190–200.

Hepokoski, James, and Warren Darcy. 2006. Elements of Sonata Theory: Norms, Types, and Deformations in the Late-Eighteenth-Century Sonata. Oxford University Press.

Kirnberger, Johann Philipp. (1771/1776) 1982. The Art of Strict Musical Composition. Translated by David Beach and Jurgen Thym. Yale University Press.

London, Justin. 2022. “A Bevy of Biases: How Music Theory’s Methodological Problems Hinder Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion.” Music Theory Online 28 (1).

Longyear, Rey M. 1971. “The Minor Mode in Eighteenth-Century Sonata Form.” Journal of Music Theory 15 (1/2): 182–229.

Martin, Nathan John. 2015. “Mozart’s Sonata-Form Arias.” In Formal Functions in Perspective: Essays on Musical Form from Haydn to Adorno, ed. Steven Vande Moortele, Julie Pedneault-Deslauriers, and Nathan John Martin, 37–73. University of Rochester Press.

Rosen, Charles. 1980. Sonata Forms. W. W. Norton.

Schmalfeldt, Janet. 2011. In the Process of Becoming: Analytic and Philosophical Perspectives on Form in Early Nineteenth-Century Music. Oxford University Press.

Sherrill, Paul. 2016. “The Metastasian Da Capo Aria: Moral Philosophy, Characteristic Actions, and Dialogic Form.” PhD diss., Indiana University.

Stevens, Jane R. 1983. “Georg Joseph Vogler and the ‘Second Theme’ in Sonata Form: Some 18th-Century Perceptions of Musical Contrast.” The Journal of Musicology 2 (3): 278–304.

Talbot, Michael. 1985. “Modal Shifts in the Sonatas of Domenico Scarlatti.” Chigiana: Rassegna Annuale Di Studi Musicologi 40 (20): 25–43.

Footnotes

1. Throughout this article, I use the English translations of Galeazzi’s terminology as translated by Deborah Burton and Gregory W. Harwood (Galeazzi [1796] 2012). Galeazzi uses “Passo Caratteristico” and “Passo di mezzo” interchangeably. Burton and Harwood use the former, translated to “characteristic passage.”

Return to text

2. These possibilities will be examined in greater detail in the section entitled “Boccherini, String Trio in A Major, G. 79, 2nd Movement” below.

Return to text

3. In the conclusion of this article, my analysis of Boccherini’s String Trio (below) will be compared to Burstein’s analysis of Beethoven’s Sonata. This comparison strongly suggests that, as far as Galeazzi is concerned, this apparent similarity is a false one.

Return to text

4. Galeazzi’s treatise has been widely examined by recent authors. Bathia Churgin (Churgin 1968) initiated the re-discovery of this work in her 1968 article discussing the composer’s description of sonata form. Gjerdingen (2007, 415–32) includes an entire chapter on this work that contains a version of the Allegro discussed below, adding a bass line clarifying the harmonic motion. In 2012, Deborah Burton and Gregory W. Harwood published the translation of Books 3 and 4 of Galeazzi’s work (this translation forms the basis of my own work). Last, Burstein 2022 includes a discussion of Galeazzi’s work, along with the work of other contemporaneous authors, in his Journeys through Galant Expositions.

Return to text

5. The date of Galeazzi’s publication (1796) and the style exemplified by the sample Allegro seem mismatched, but this is not necessarily the case. The pedagogical intent of this treatise is paramount to understanding the Galeazzi’s materials. Galeazzi plans his materials meticulously, keeping his reader, the amateur musician, in mind. He suggests further study using the compositions of Haydn and Boccherini—both well-established, living composers whose works were widely available. When demonstrating his ideas about musical form, he opts for a short, tailor-made Allegro that will not overwhelm or distract his reader. Furthermore, the ideas that Galeazzi presents about musical form work well for mid- and late-century compositions. In this article, I emphasize their application to the former. Burstein’s Galeazzian analysis of the first movement of Beethoven’s Piano Sonata in C Major, op. 2, no. 3, discussed in the conclusion, demonstrates their efficacy in the analysis of late eighteenth century works.

Return to text

6. Galeazzi does not specifically mention unexpected minor-mode passages in the exposition. Again, the pedagogical nature of the treatise provides an explanation. Galeazzi’s work is for interested amateur musicians, and not for professionals. His explanation of composition and musical form focuses on basic, normative compositional practices. The successful use of these minor-mode passages in the exposition is beyond the scope of that work.

Return to text

7. My overview here is drawn primarily from Galeazzi’s example, which itself is similar to what occurs in my examples below. Galeazzi’s discussion of the exposition includes far more possibilities than this (2012, 324–29). My interpretation frequently overlaps with and draws on Burstein’s interpretation of Galeazzi’s ideas. This is especially true of the discussion of the bipartite division of Galeazzi’s exposition compared with modern models (2020, 91–95).

Return to text

8. Those interested in comparing Galeazzi’s ideas with those of other eighteenth-century theorists should explore Chapters 4 and 5 of Burstein’s Journeys. These chapters provide an overview of the work of Koch, Galeazzi, Riepel, August Friedrich Christoph Kollmann, and Franz Christoph Neubauer, along with some points of contact between the theories.

Return to text

9. Stevens’s work from 1983 predates the “new Formenlehre” that has come to dominate the discourse in the past thirty years. Her work is perhaps best understood in the context of Leonard Ratner’s work on Classical form.

Return to text

10. Burstein also invokes the idea of a sentential presentation phrase (the characteristic passage) followed by a continuation (cadential period) in his analysis of these sections (2020, 92–93). While organization similar to this occurs frequently in the examples below, the results are not always a clear sentence occurring across the characteristic passage and cadential period.

Return to text

11. Burstein specifically discusses this passage and its relationship to Galeazzi’s characteristic passage as well as the idea of “secondary theme” in his book (Burstein 2020, 110–112).

Return to text

12. Naturally, there are dangers that come with such an appropriation. Although we know the purpose of Galeazzi’s work, much of the original context is lost. Even if we delved into the philosophical, geo-political, and cultural underpinnings of these ideas, we are still examining them from a point of remove and from the basis of the limited number of extant works and writings by Galeazzi.

Return to text

13. Conclusions of the various formal sections will be identified by the harmony on which they conclude. In the case of characteristic passages, I focus on the rhetorical strength of the passage’s conclusion, but designating these endings as cadences vs. resting points—or, more frequently, something in between—is not particularly helpful in this context.

Return to text

14. Those familiar with Koch’s work may find the repetition of the V/V resting point at the conclusions of the departure and the characteristic passage interesting, as it seemingly violates Koch’s “rule” against repeated Absätze. The departure and characteristic passage, however, may best be understood as an example of Koch’s pairing of rauschende and cantabile Quintabsätze (2020, 61–63).

Return to text

15. The passage in the String Trio might best be understood as a single passage fusing the TM1 and TM2 portions of the trimodular block (Hepokoski and Darcy 2006, 172–75). Both Rey M. Longyear and Charles Rosen discuss minor-mode beginnings to the secondary key area as characteristic of the mid-eighteenth-century style. Longyear (2020, 204) calls these instances one of the “hallmarks of the pre- and early-Classical sonata form,” while Rosen (1980, 146) characterizes them as a “mid-[eighteenth] century stereotype.”

Return to text

16. This is true even of Longyear and Rosen’s discussions cited above. Although the authors discuss these in the context of mid-eighteenth-century sonata form, that context is provided by a comparison to perceived late-eighteenth-century norms.

Return to text

17. The two optional bookend sections—the prelude and the coda—are also said to typically conclude with cadences. The prelude’s cadence is “either expressed or implied, at the moment when the [principal] motive starts” while the coda merely extends, prolongs, or reiterates the cadential period’s cadence (Galeazzi [1796] 2012, 326). Most eighteenth-century authors recognized a cadence at the conclusion of what Galeazzi calls the cadential period. Koch, for example, describes a series of “resting points” that lead to a cadence in the secondary key. Galeazzi’s inclusion of the cadence at the end of the departure is of particular interest. It would seem to reflect increased use of a cadence at that point by the time Galeazzi is writing (1796).

Return to text

18. Caplin (1998, 195–96) discusses some of the deficiencies of this model as well as those of a second, “tour of keys” model in his chapter on sonata form.

Return to text

19. Galeazzi’s description of keys includes a limited number of parallel major and minor pairs (often because the minor key is “proscribed from music of good taste” or similar). His description of A major and A minor provide a useful example. A major is “extremely harmonious, expressive, affectionate, playful” and so forth, while A minor is “lugubrious and dark

Return to text

20. Scarlatti’s works received limited publication until the twentieth century; what remains of Seixas’s work (the majority was destroyed in Lisbon in 1755) was also primarily published during the twentieth century.

Return to text

21. Boccherini was Italian and Haydn, though Austrian, worked closely with the Italian composer Nicola Porpora (Feder and Webster 2024).

Return to text

22. Works where a significant portion of the secondary key area or of the exposition occur in an unexpected mode present a separate analytical situation. The use of the minor mode in such movements goes well beyond temporary, local contrast.

Return to text

23. Indeed, motion to the parallel minor is possible at any point in the exposition. My focus on the characteristic passage here stems in part from the stark differences in how these passages are treated. From Galeazzi’s perspective, they are a passing point of contrast outside of the main action of the tonal trajectory, while from modern perspectives, they may be considered a dramatic event at an important point within that tonal trajectory.

Return to text

24. The first movements of the String Trio in F Major, G. 77 and the Cello Sonata in F Major, G. 1 also feature half cadences at the end of their respective characteristic passages.

Return to text

25. Janet Schmalfeldt discusses the dramatic implication of a minor-mode passage in the Act I trio, “Cosa sento!,” from Mozart’s Le Nozze di Figaro. The passage’s gradual accrual of minor-mode traits coincides with Susanna’s growing anxiety in the scene (Schmalfeldt 2011, 80–86). Nathan John Martin analyzed a similar situation in Belmonte’s aria, “O wie ängstlich,” from the first act of Mozart’s Die Entführung aus dem Serail. Again, the emotional shift portrayed by the minor mode is anxiety—here, Belmonte’s anxiety at seeing Konstanze again (2015, 42n17).

Return to text

26. Specifically, Le Trésor des pianistes includes Benda’s Keyboard Sonata in F Major, Paradies’s Keyboard Sonatas Nos. 6 and 7, and Scarlatti’s Keyboard Sonatas K. 6 and K. 211. It also includes many other works that feature turns to the minor mode at other points during the exposition.

Return to text

27. This article not only provides Burstein’s analysis, but also neatly summarizes the various, disparate analyses of this exposition that have been previously published.

Return to text

28. The interpretation of a passage beginning in anything but the tonic as the second motive may strike contemporary readers as odd, because we tend to think of the secondary key’s onset as occurring later in the form. But in Galeazzi’s discussion of sonata form, he includes the possibility of the second motive beginning in the dominant (though, admittedly, not the minor dominant).

Return to text

Copyright Statement

Copyright © 2024 by the Society for Music Theory. All rights reserved.

[1] Copyrights for individual items published in Music Theory Online (MTO) are held by their authors. Items appearing in MTO may be saved and stored in electronic or paper form, and may be shared among individuals for purposes of scholarly research or discussion, but may not be republished in any form, electronic or print, without prior, written permission from the author(s), and advance notification of the editors of MTO.

[2] Any redistributed form of items published in MTO must include the following information in a form appropriate to the medium in which the items are to appear:

This item appeared in Music Theory Online in [VOLUME #, ISSUE #] on [DAY/MONTH/YEAR]. It was authored by [FULL NAME, EMAIL ADDRESS], with whose written permission it is reprinted here.

[3] Libraries may archive issues of MTO in electronic or paper form for public access so long as each issue is stored in its entirety, and no access fee is charged. Exceptions to these requirements must be approved in writing by the editors of MTO, who will act in accordance with the decisions of the Society for Music Theory.

This document and all portions thereof are protected by U.S. and international copyright laws. Material contained herein may be copied and/or distributed for research purposes only.

Prepared by Aidan Brych, Editorial Assisstant

Number of visits:

4178