Three Sailors, Three Personalities: Choreomusical Analysis of the Solo Variations in Fancy Free

Rachel Short

KEYWORDS: Dance, movement, ballet, choreomusical analysis, Bernstein, Robbins, choreography, rhythm/meter, entrainment, staged characters, performances, metric dissonance, meter

ABSTRACT: A thorough understanding of how music and movement synthesize is vital for deeper exploration of multimedia artworks. In this article, I demonstrate a choreomusical analytic technique that links detailed analyses of both music and choreography from the ballet Fancy Free, a work that was the product of a close collaboration between Leonard Bernstein and Jerome Robbins. Specifically, I explore the three sailors’ solo variations, noting placement and repetition of rhythmic and choreographic phrases, elisions and metric changes, and reinterpretation of rhythmic patterns. I observe differences in grouping and accents to reveal how the changing relationships between dance and music create unique characterizations for each of the sailors. My integrated reading of music and original choreography explores the relationship between music and movement, offering a way to understand how they intertwine.

DOI: 10.30535/mto.30.3.5

Copyright © 2024 Society for Music Theory

Introduction

[0.1] A thorough understanding of how music and movement synthesize is vital for deeper exploration of a multimedia artwork. In this article, I demonstrate a choreomusical analytic technique that links detailed analyses of both music and choreography to a selection from the ballet Fancy Free. Specifically, I investigate the three solo dance variations to demonstrate how placement and repetition of rhythmic and choreographic phrases, elisions and metric changes, and reinterpretation of rhythmic patterns create unique characterizations for each of the portrayed personalities. My integrated reading of musical scores and original choreography explores the relationship between music and movement, offering a way to understand how they intertwine.

[0.2] The 1944 premiere of the ballet Fancy Free by the Ballet Theatre (now known as the American Ballet Theatre) marked the beginning of the creative collaboration between composer Leonard Bernstein and choreographer Jerome Robbins. Although there are numerous biographical accounts of Bernstein and Robbins, few scholars have focused on how their creative activities intersect. In my analysis, I consider music and dance structures both on their own and aligned together to see how they inform each other. The musical framework focuses on rhythm and meter, paying close attention to musical accents, phrase lengths, perceived and notated time signature changes, and larger formal sections. The dance framework examines the original choreography, noting how dance accents correlate with rhythmic accents and changes in meter, and looks at larger sequences of steps, which I term “choreographic phrases.” Combining the two frameworks, I explore correspondences and conflicts in grouping, hypermeter, and accents. This approach proves particularly fruitful when studying the variations in Fancy Free’s sixth movement; it furnishes insight into the characters of the three sailors who are the work’s protagonists. I show how combined creative choices in the music and choreography distinguish each sailor’s unique personality.

1. Theoretical Context: Choreomusical Analysis with a Rhythm & Meter Focus

[1.1] The theoretical framework behind this type of choreomusical analysis culls research from two disciplines: choreomusical scholarship on dance and music-theoretical scholarship concerning rhythm, meter, and embodied understanding. A focus on the experience of someone listening to the music without considering the visual or physical input can leave an analyst with only a partial picture. Incorporating the visual movement element adds a rich perspective to the separate experience of listening to music alone, especially with music created to be danced to and encountered in tandem with a staged performance.(1) Conceiving of ballet music as intended specifically for dance is important because choreography can influence an audience member’s perception of the meter. The analyses in this article proceed by exploring how the music sounds, then comparing notated with heard meter, and then adding the choreographic layer. While each individual observer will necessarily engage with music and dance differently, some generalizations are possible.(2) Exploration of the various ways music and dance can synthesize is important with music created to be danced to, whether in a social setting, or choreographed performances.

[1.2] Choreomusical studies is a burgeoning area of scholarship that examines the relationship between dance and music.(3) While literature from this field includes insightful contributions from both music and dance scholars, engaging both areas can be complicated; as a result, scholars often tend to favor one discipline over the other. Some of the problematic issues faced early on by interdisciplinary scholars combining the fields of dance research and musicology/music theory are discussed by Jordan (2011).(4) Authors have tended to look more at critical theory, performance studies, or historical musicology instead of analyses that explore music-theoretical concerns.(5) Scholars with backgrounds in dance often use methodologies that tend towards broad categorization or description in lieu of detailed musical analyses.(6) More recently, scholars have devised new tools based on known analytical methods to explore dance,(7) and recent scholars have explored various ways to notate dance and music.(8) For example, Leaman’s (2021a, 2021b, 2022) choreomusical scores visualize dance and musical elements together, showing vertical placement of the dancers’ bodies as they occur in time to explore the musical artistry of a specific choreographer.(9) Simpson-Litke’s (2021) choreographic salsa scores combine detailed footwork patterns with musical transcriptions, exploring how improvising dancers attend to various musical features.(10) My work takes a larger, character-driven focus better suited to a constructed ballet format, incorporating historic and cultural insights and showing how choreomusical analysis—particularly at the phrase-level—can explain how music and visual elements intertwine to further the creation and development of onstage characters.

[1.3] My musical analysis begins with a conceptual framework partially modeled after those of Lerdahl and Jackendoff (1983), Krebs (1999), and London (2012), who explore rhythm and meter, overlapping hierarchical layers, entrainment concerns, musical accents and phrases, and metrical dissonance.(11) I expand Krebs’s concept of different layers creating grouping and displacement “dissonances” in music to include dance groupings as well as musical groupings.(12) As such, my choreographic analyses supplement recent discussions of rhythm and meter for an embodied listener by helping to clarify metric construals and delineate formal boundaries.

[1.4] For my choreomusical analyses, I broaden the concept of entrainment—how we internalize meter in music we hear—to include ways in which the dancers’ rhythmic movements contribute to the entrainment process of an idealized observer watching a ballet performance. Cox’s (2011, 2016) explorations of the mimetic hypothesis offer a way of theorizing our embodied experiences of music, which has particular implications for analyzing meter. London (2012), van den Toorn (1987), and Gjerdingen (1989) see meter as “a mode of attending.”(13) To enhance that view, I would fold in the visual modality: I argue that watching dance can affect an attending strategy, as rhythmic movement can help to encourage a particular metric interpretation.(14) Visualizing the additional accents and groupings created by a dancer’s movements affords an observer more to attend to; this information may reinforce or obscure insights gained from a solely musical perspective. Even for an audience member sitting and watching a performance, motor aspects—the bodily activity of the dancers on stage—may influence the metric entrainment of the observer.(15)

[1.5] Choreography itself already represents a type of musical analysis by the choreographer and dancer; in this study, I place movement analysis in dialogue with traditional musical analysis, reading more deeply into how dance and music can correlate.(16) Beyond noting their correspondences, I also look at how dance and music can come into conflict, or non-alignment, and when those shifts happen. Just as metrically conflicting passages in music necessitate greater attention and can therefore elicit more excitement from audience members, sections where dance and music are in opposition can generate energy and momentum.(17) These frictions between music and choreography often produce dramatic effects; in the wake of exertion-filled sections, sudden correspondences between music and dance can then establish a combined climax or structural downbeat.(18) I explore changing levels of correlations between dance phrases and musical phrases—involving higher-level hypermetric groupings and lower levels of metrical dissonance—to clarify musical ambiguities, inform metrical and thematic elisions, amplify sections of phrase overlap, and explicate formal structures.

[1.6] Dance critics and analysts have long been fascinated with how choreographic accents and phrases correlate with musical accents.(19) Unlike their musical equivalents, dance accents can be points of emphasis that do not necessarily coincide with a step’s onset or duration; often accents occur at the apex of a jump or turn, the outermost point of a kick, or the lowest point of a bend (plié).(20) As well as accents created by visual movement, dance accents can also include moments of movement cessation, such as a held pose or a break in the dancing, and accents that create sound by physical means.(21) I define “body percussion” as choreographed movement that includes intentional and meaningful production of sound, such as claps, snaps, or hands slapping against thighs.(22) I call larger sequences of linked steps “choreographic phrases.” While individual creators’ styles vary, the boundaries of choreographic phrases are marked by salient elements including repetition and parallelism, directional shifts, and conventional step expectations within a genre. The delineation of choreographic phrase boundaries is a helpful aid for those seeking to understand choreographic structures, especially in cases when the perceived beginning of individual steps is not clear. While an observer’s metrical attending can affect their perception of dance accents, conversely, accents and phrases in choreography can affect one’s metric understanding. Dance accents can help to clarify aspects of a musical passage that are, as London would define, metrically ambiguous, or those with disrupted entrainment possibilities.(23) Leonard Bernstein’s music, as will be shown below, offers an unusual wealth of entrainment possibilities that can be confirmed or thwarted by choreography.

2. Bernstein, Robbins, and Fancy Free

[2.1] To establish the ballet Fancy Free as a case study for this style of choreomusical analysis, I next offer a brief contextual history. The account will serve to explore and relate Bernstein’s understanding of rhythm and meter and to provide critical background information about the original production and performers.

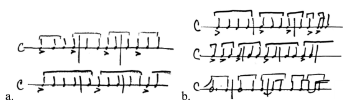

Example 1. Bernstein, beat-grouping “distortions”

(click to enlarge)

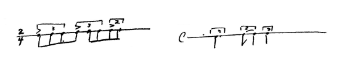

[2.2] Before music scholars developed modern models of grouping dissonances and other rhythmic and metric subjects, Bernstein explored analogous concerns in his 1939 thesis.(24) Certain aspects of Bernstein’s language and ideas are regrettably nationalistic and outdated; nevertheless, his discussion highlights rhythmic and metric principles that came to be featured prominently in his own later works, particularly rhythmic diminution, augmentation, and beat-grouping. In Example 1, Bernstein diagrams what he calls “beat-group distortions”: a) beat-groupings of three and five beats within four-beat measures and b) beat group diminution, beat group augmentation, and diminution of a rhythmic figure ([1939] 1982, 64–65).(25) Some of these rhythmic “distortions” are forerunners of what Krebs would later call grouping dissonances.

[2.3] One important implication of Bernstein’s analysis of beat-group distortions is how rhythmic elaboration and development in the music often create groupings that contradict the notated

[2.4] Bernstein, furthermore, had an intuitive understanding of what later theorists would characterize as rhythmic expectations and metric entrainment. Being interested in the ways a composer could shape rhythm to manipulate a listener’s expectations, he gave deep consideration to the listener’s perspective, both with respect to how the music “feels” and how rhythmic and metric precedents, once created, influence subsequent expectations.(29) In his discussions of highly syncopated American music, Bernstein stressed the importance of an underlying beat.(30) Bernstein’s own music frequently exhibits motivic repetition over a constant pulse, an arrangement particularly suited for playing with listener expectations. In the narrative ballet Fancy Free, this rhythmic play in the music combines with the onstage action to tell the story and to establish and develop its characters.(31)

[2.5] As a way to explore the unique characterizations resulting from music and movement working in combination, this article focuses its choreomusical analysis on the only section in Fancy Free that features individual dancers: the three solo variations for the sailors in the sixth movement. I point out personality-defining musical and choreographic moments, arguing that the combined metric and rhythmic choices in the music and choreography produce the unique characterization in each variation.

Example 2. Plot Layout for Fancy Free from Robbins to Bernstein

(click to enlarge)

[2.6] This collaboration between Robbins and Bernstein was unusually choreographer-centric.(32) While choreographers usually work with a preexisting score, for Fancy Free Robbins gave Bernstein a detailed diagram indicating what should happen at each point in the plot. Robbins’s plot outline follows a story of three sailors arriving in the city for a night on the town during one of their shore leaves. He mapped the rise of competition between the sailors in the plot layout shown in Example 2.(33) In this outline, #6, which denotes the three solo dances, occurs near the apex of the overall tension. Once Bernstein had composed a musical draft to meet these criteria, Robbins specified changes he wanted Bernstein to make to the score to fit the narrative.(34)

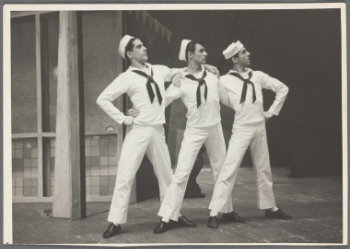

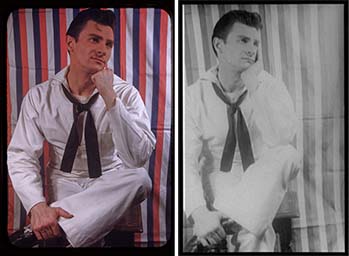

Example 3. Images of the Trio

(click to enlarge and see the rest)

[2.7] Part of the reason Fancy Free struck a chord with the American public was that it was something they could relate to, a familiar wartime scene with realistic characters. The characters portrayed likely came across as even more poignant because they were all based on Robbins’s close friends, with whom he had an established rapport (see Example 3, Fehl 1944a). Dance historian Jowitt (2004, 79) notes how “the cast members were all his friends, and he built not only on their particular dancerly strengths but on how he saw them as people.” The scenario by Robbins specifies this familiarity between the sailors, stating, “One should feel immediately that the three are good friends, used to bumming around together, used to each other’s guff

[2.8] The original cast, in turn, realized that he was working to incorporate their individual personalities into the production. Harold Lang told writer Tobi Tobias in 1980: “I think he took out of us what would be—not exploitable, but usable. Jerry himself had a good Latin feeling to him, he saw Johnny as being lyrical, kind of dreamy and sweet—a country boy, and I guess he saw me as a show-off” (quoted in Gottlieb 2008, 1147).(36) These close working relationships between the original cast members aided Robbins in choreographing robust onstage characters that resonated with the audience.

[2.9] The characters are still interesting today, even in a society with evolved views on cultural stereotypes and interactions between genders. Some now view the piece as a dated period piece, which romanticizes what likely now would be viewed as harassment and catcalling. In a recent opinion piece, Cecelia Whalen (2018) wonders, “parts of it have not stood the test of time, yet as a whole, it remains. Why? Undoubtedly, it has to do with the music. Bernstein’s score can be upbeat but also touching and Robbins’ choreography plays with every single accent.” An additional answer is provided by Boston ballet’s principal dancer, Kathleen Breen Combes, who recently noted: “Ultimately, this piece represents human relationships. Each character is very authentic and they represent hope and a celebration of a time in our history” (2018). The onstage characters, both now and at the time of their premiere, remain remarkable and memorable because of the meticulous mixture of music and dance that created them.

[2.10] At this point in the ballet, the protagonists are “On the Town” (the title of a popular 1945 Broadway musical from the same creative team, which was roughly based on the ballet’s plot), and the three sailors have already met two women, resulting in an unfavorable ratio for the hopeful suitors. To impress the ladies and increase their chances, each sailor dances a solo, the only time in the ballet where their discrete personalities are highlighted by individualized music. The singular character of each sailor comes through, in both the music and the choreography: Sailor One is an acrobatic show-off, Sailor Two is shy and unassuming, and Sailor Three is a leader who moves his hips with flair.

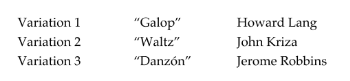

Example 4. Variation Titles; Movement VI

(click to enlarge)

[2.11] While distinct, the three variations manifest some common traits. They are all roughly ABA form, they all musically trail off at the end, and all feature a title naming a dance style that corresponds to their different personality: a Galop, a Waltz, and a Danzón (see Example 4). The overall style of movement is mixed: many steps are recognizable from the classical ballet repertoire, and Robbins incorporates elements from American vernacular dance, inserting many steps that hearken to soft-shoe and “tap” moves.

3. Musical and Choreomusical Analysis, Variation 1: “Galop”

[3.1] The character portrayed in the energetic first variation is that of an acrobatic, gregarious sailor. As Robbins describes the character in the scenario, “The first is the most bawdy, rowdy, boisterous of the three. He exploits the extrovert vulgarity of sailors, the impudence, the loudness, the get-me-how-good-I-am” (reproduced in Amberg 1949, 136–37). The animated and enthusiastic choreography interacts and combines with music to effectively convey this full sense of the character.

[3.2] The lively disposition of Sailor One is well-matched by the upbeat, steady tempo of the variation, aptly titled a “Galop.”(37) Comparatively speaking, the music is quite conventional, exhibiting a steady

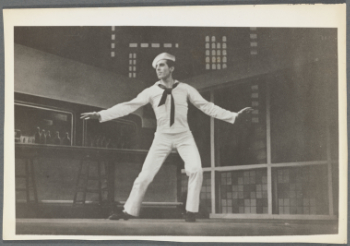

Example 5. Harold Lang (Sailor One) lands a double tour en l’air in the splits

(click to enlarge)

[3.3] Robbins’s choreography helps portray the acrobatic and gregarious Sailor One through grandiose leaps, jumps, and turning steps paired with showy gestures. As Harold Lang, the first dancer in the role, said of the character’s movements, “[Robbins] put in all the things I liked to do: pirouettes, air turns—a lot of high movements, extensions, and jumps. Jumping on the bar, things like that: it seems like I’m always on the furniture” (quoted in Gottlieb 2008, 1147). And indeed, the choreography is full of bombastic movements, such as triumphantly raised arms in a “V” for victory, gallant bows, forward rolls (somersaults), and multiple spins: the sailor turns around seven times before the first seven measures are completed. The variation starts off with a bang—a double tour en l’air (turn in the air) that lands in the splits, shown in Example 5 below ([unknown artist] 1944a).

Example 6a. Mvt. VI.1, Overall formal layout: hypermetric phrases, elisions

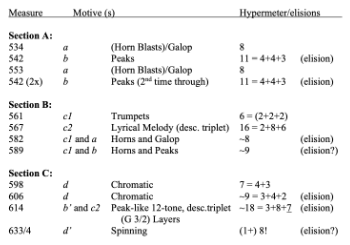

(click to enlarge)

Example 6b. Mvt. VI.1, Main motives

(click to watch)

[3.4] The variation’s music features frequent anacruses and motivic repetition within a larger three-part form that is structured as follows: A=534–60, B=561–98, and C=598–641. Example 6a outlines the formal layout of the variation, showing repetition and combination of motives a, b, c and d within a tripartite form, hypermetric lengths, and elisions between phrases.(38) Main motives are introduced early: three initial horn blasts are followed by melodic motives with constant eighth-note motion that I term a-galop and b-peaks, the latter because of the similarity of the melodic line to a range of mountain peaks (or ocean waves). To begin B (the second large section), c is divided into two parts: (c1) a simple two-bar trumpeting pattern; and (c2) a lyrical melody with triplet rhythms that includes a descending third melody familiar from earlier movements. Fragments of a and b are then interjected in combination with c’s rapping trumpets. These motives can be heard in Example 6b.

[3.5] Especially when hearing this opening music without a score, a listener is likely to experience confusion about where the downbeat (or emphatic “1” accent) is; that is, how the two beats fall within each

Example 7. Mvt. VI.1, mm. 534–554, showing hypermetric ambiguity

(click to enlarge and listen)

[3.6] Example 7 shows Bernstein’s motivic use of anacruses and hypermetric ambiguity at the beginning of the movement, as repeating motives vary their positions in terms of upbeat/downbeat (DB) placement. Integers between staves show the underlying hypermeter. The primary arrangement of two-bar pairs of strong/weak measures is sometimes obscured due to the placement of the horn’s melodic fragments. The first group of three horn blasts begins on beat one of m. 534 and spans one and a half measures, which equals “1+2” on the next hypermetric level up; the galop motive then confirms this hypermetric understanding. Four bars later (m. 537), two similar horn bleats begin on beat two, or the “+” of the next hypermetric level. This may confuse a listener who expects an accented attack on “1+2” as before, because this time the attacks begin on the “+.” The last three horn blasts may be heard either as an anacrusis on “+1+,” or as 1+2, like the beginning. Either the strong-weak hypermeter is interrupted, or the motivic fragments are displaced.

[3.7] The elisions in Variation 1 mostly affect the hypermeter; an early example of hypermetric elision is seen in the last bar of the passage shown in Example 7. Starting at m. 542, analytical blue slurs show the two-bar subphrases. A vertical line between mm. 552–53 marks where a two-bar subphrase is only halfway completed when another begins: the three strong chord blasts from a result in an elision that interacts with the previous downbeat/upbeat confusion. Occasionally, abrupt changes in orchestration seemingly create potential elisions, but in actuality the two-bar subphrases continue (for example, at mm. 596 and 633).

[3.8] The choreography interacts in various ways with larger musical phrases. Often, steps are organized into four- and eight-bar phrases, but these do not always align with the musical phases. The choreography can help an observer understand hypermetric confusions and elisions, and some musical additions seem to be added to support longer dance phrases. Yet sometimes the dance steps further confuse the notated meter, and there are some contradictions: grouping dissonances between musical and movement phrases create additional tension towards the end of the variation.

Example 8. Mvt. VI.1 mm. 534–554, choreomusical analysis, motives a and b

(click to enlarge and watch in new tab)

[3.9] As shown in Example 8, at the beginning of the variation the choreographic phrase confirms the larger musical hypermetric eight-bar phrase, smoothing out its irregular partitions this is indicated with a dotted orange bracket). The dancer begins in silence broken by a drumroll. He anticipates the orchestral downbeat by circling each foot behind his standing leg, letting the power build as he prepares to show what he is made of. A brief plié prepares him for a high jump with multiple turns in the air (tour en l’air), until he lands in the splits to correspond with the orchestral hits that begin the music. Sailor One’s plié preparation for more pirouettes happens on the notated downbeat of m. 538; while this movement could confirm a downbeat there, its occurrence with the second of two orchestral hits may further confound the listener. Sailor One completes the pirouettes with his legs apart to highlight the musical accents over the barline (mm. 540–41), clasping his hands above his head to pump them twice high in the air in a “victory” gesture (V!). This motion serves as a seam between the irregular musical subphrases assembling the first eight bars.

[3.10] Measure 542 begins a repeated sequence of dance steps. In the examples, solid orange slurs indicate choreographic phrases. Here, these phrases are delineated by a parallel sequence of well-defined movements that are clearly repeated in a different direction. The traveling sequence is repeated two full times, towards the group at the table then back towards the center. A third sequence is initiated but cut short by a modified ending: a similar jump from the initial drum roll, which once again lands in the splits on the downbeat. This shift turns beat two of the two-bar hypermeter into an understood downbeat after the elision: after the musical repeat, m. 553 ≈ m. 534. The rhythmic confusion caused by irregular motivic placement in the first eight measures of music is heightened by the dancers’ phrasing, which strengthens the effect of the elision.

Example 9. Mvt. VI.1, mm. 559–562, choreomusical analysis, second time through

(click to enlarge and watch in new tab)

[3.11] After Sailor One’s second land in the splits, the initial choreography is replicated during the repeat of the motive a music (mm. 553–60). But the second time through, motive b is accompanied by new choreography featuring accents that modify the felt downbeat placement (see Example 9, mm. 559–62). Robbins could easily have opted for an exact repetition of the choreography on the same beats; the decision to make it offset provides a more boisterous characterization for the charismatic sailor. Initially, the choreography for the first phase (the repeat of mm. 542–45, shown with a dotted orange slur) has a downward preparation (plié) on the anacrusis (d) and a kick up (U) on the downbeat (upper-case letters denote downbeat placement); during the second choreographic sequence, the lowering plié happens directly on the downbeat (D) with the kick on the second beat (u). The slightly different rhythmic placements of the physical movements strongly impact the way the meter is felt, a sensation that resembles the changes in how downbeats are felt throughout the movement.

Example 10. Mvt. VI.1, mm. 614–633, G 3/2 layers of grouping dissonance

(click to enlarge and listen)

[3.12] The music heard and seen in Example 10 from Section C shows an example of how various orchestral levels interact to generate a phrase-level 3/2 grouping dissonance, with a final orchestral elision at m. 633.(40) Higher woodwinds, strings, and piano repeat a chromatic leaping pattern that amasses a twelve-tone series every three-measures: E–C#–D–G C–B–Bb–F F#–A–Eb–Ab, or 4127 0ET5 6938. The row repeats five times and begins a sixth time before it dissolves. This causes a grouping dissonance with the familiar descending triplet melody—heard this time in the trombones instead of the trumpets—which continues a previously established symmetrical pattern: four-bar phrases made up of two-bar groups, including the anacrustic pickups common in the variation. An asterisk marks the place where the series breaks off, and the dotted slur and line show the disintegration of the three-bar phrase. Layered grouping dissonances between melody and orchestral accompaniment add excitement as the variation nears its climax.

[3.13] Within this atmosphere of hypermetric play at both larger and smaller levels, “standard” eight- and sixteen-bar phrases are thrown into relief. The most striking instance of this is in section B (see Example 6a), where two clear eight-bar phrases combine to form a larger group of sixteen. Another notable symmetry is found toward the end of the movement (d’, mm. 634–41), where a variant of the three-note chromatic rise from d repeats six times until continuing up to the tonic to close the eight-bar phrase. These symmetrical phrases signal closing function, highlight the final acrobatic spinning sequence in the choreography, and gather up hypermetric loose ends in the variation for a robust finish.

Example 11. Mvt. VI.1, mm. 582–590, choreographic support of motives

(click to enlarge and watch in new tab)

[3.14] While the limited symmetrical music in the movement is matched with symmetrical choreography (notably, the four-bar phrases in mm. 567–81), much of the music is not symmetrical, and the choreography does not always clarify the musical grouping and phrasing. Often, the choreography heightens metric tension, as the steps correspond with and bring out the shorter musical fragments at the expense of the notated barlines. A case in point is mm. 582–90 (horns and gallop motives). As shown in Example 11, the music in this section is metrically unclear, as the interjected melodic fragments of horn blasts and melodic peaks are metrically displaced upon repetition (blue slur lines under the staff show how the implied two-bar phrases overlap, blue brackets show motivic placement). This is a metrical conundrum that the choreography clarifies (orange brackets). On the third horn blast, the dancer’s arms extend in a pose of “V for victory,” then he bows during the b-peaks. At the end of the larger phrase, the overhead arm pump with clasped hands gesture returns from the beginning of the movement as filler during the elision until the next phrase begins at m. 591 (shown with asterisks). The choreographic phrases correspond with motivic fragments, not with notated downbeats, and the constantly changing metric feel establishes the energetic character of the sailor.

[3.15] As the first variation nears its end, the sailor jauntily tightens his hat and prepares for a large circle of leaps and turns known as a “manège en tournant.” A manège circle was a conventional climax of male variations in many classical ballets, especially the Russian ballets that the American Ballet Theatre had recently been performing. In this setting, Robbins brings his distinct “American” perspective to it. The sailor starts by traveling clockwise with traditional energetic leaping and turning steps (known as sauté and coupé, respectively). To complete the traditional sequence, a straight-leg split leap (or grand jeté) is expected next (the entire sequence is known as jetés en manège or coupé jeté en tournant). Instead of the traditional straight-leg split leap, Robbins has the dancer bend both legs and bring them in front, slapping his knees with his hands while turning in the air. This modified leap is closer to a barrel roll—a colloquial musical theatre step—than the classical grand jeté. The body percussion of hands slapping thighs also is different from a traditional manège, where the only sounds would be those of the dancer’s feet as they land on the floor (though note: professional ballet dancers often attempt to minimize these sounds).

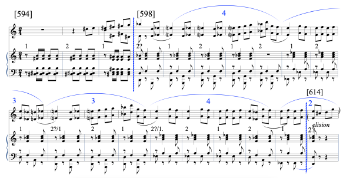

Example 12a. Mvt. VI.1, mm. 594–614, elisions and hypermetric play

(click to enlarge and listen)

[3.16] Building on prior metric uncertainty, the music for the manège circle illustrates Bernstein’s hypermetric play with larger phrase groups (see Example 12a). At mm. 596–97, abrupt changes in orchestral accompaniment in the middle of an established two-bar pattern seemingly create an elision, yet the melodic phrases quickly assure the two-bar hypermeter is still in place. Further hypermetric play begins at m. 598, which starts a chromatic melody d in call-and-response style with an ascending antecedent and descending consequent. A three-note chromatic motive is repeated three times during the phrase’s initial ascent and only twice on its initial descent, which creates uneven hypermetric phrases of four and three bars. On its repeat, the pattern is reversed, resulting in an overall <4334> arrangement before a short, two-bar “outro” transitions into the next section. At m. 614, the hypermetrically strong measure of the next phrase of d begins on the weak measure of the last phrase.

Example 12b. Mvt. VI.1, mm. 598–614, grouping dissonance

(click to enlarge and watch)

[3.17] Tension in the large manège circle mounts through the combined impact of the dancer’s continued energetic leaps, the inherent drive of the traveling manège, and a grouping dissonance that pits the irregular layers in the music against layers of four in the dance, as shown in Example 12b. The dancer repeats a four-bar sequence four times (orange slurs), counted “1-2-3-4-5-6-7-8,” with the step sequence sauté, coupé, “jump-with-knees-in-the-air.” This creates a grouping dissonance when layered against the irregular melodic phrases (blue slurs: <4334> plus the added two bars at the end). The strongest grouping dissonance occurs at the end of the second eight-beat choreographic sequence of steps, as indicated with two exclamation points. The choreographic phrasing also explains the extra two-bar phrase. Though musically extraneous, it is required so that the musical section ends with the dance sequences (4+3+3+4+2=16=4*4). The video excerpt accompanying Example 12b illustrates how metric correspondences and conflicts between music and dance in the manège circle create a uniquely energetic character for Sailor One.

[3.18] Robbins ends the sequence by positioning the sailor in a challenging, angled balance, left leg high to the side, foot flexed, and hands clasped above head as he winks and smiles triumphantly at the ladies. This choreographic choice ends the variation as rambunctiously as it began. For spectators, the choreographed dance steps during the cocky variation alternately aid and complicate their navigation of the music’s metric confusions. Sometimes, dance phrases explain musical elisions and clarify musical additions. At other times, the grouping dissonance produced by layering choreographic phrases onto musical phrases—such as the big turning and jumping manège circle close to the final climax—creates energy and forward momentum. The amalgamation of these creative choices presents the sailor’s character as a force to be reckoned with, a challenge to the other two sailors.

4. Musical and Choreomusical Analysis, Variation 2: “Waltz”

[4.1] In a striking contrast, Sailor Two in the second variation is depicted as lyrical, dreamy, and playful. This portrayal is achieved through a combination of gracefully curving, elegant steps along with sweet and fluid music. Entitled “Waltz” by Bernstein, the majority of the variation has a waltz feel, despite the relative rarity of music notated in steady

Example 13. John Kriza (Sailor Two): “kind of dreamy and sweet”

(click to enlarge)

[4.2] John Kriza, shown in Example 13 (Van Vechten 1949a and 1949b), originated the role of Sailor Two. Kriza was described by his friends as “lyrical, kind of dreamy and sweet—a country boy,” a far cry from the boisterous energy of the first sailor (Gottlieb 2008, 1146). Muriel Bentley reminisced how “Jerry really caught Johnny in that role

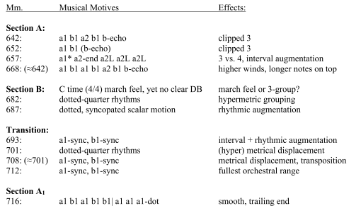

Example 14. Mvt VI.2, overall formal layout: motives, rhythmic effects

(click to enlarge)

[4.3] Bernstein uses a variety of rhythmic effects to increase metrical interest, including shortened or clipped beats, frequently switching meters, and waltz-like grouping effects that belie the notated meter. These rhythmic effects help to create motivic development, so that this seemingly simple and repetitive piece is full of development and change. Example 14 provides a formal summary of musical motives, rhythmic effects, and the larger ternary form of A–B–(transition)–A. Bernstein develops familiar motives in various ways: adding and changing instruments, inserting smaller motives to enlarge familiar motive chains, and combining neighboring motive pairs into novel sequences.(42) The nominal tonal center of G major is constantly in flux. Clear-cut cadences are limited, as most sections transform and transition into succeeding ones with elided melodic phrases. Tension builds to a central apex, then releases going into the final section. While all three variations are in tripartite form, with both the second and third in rough ABA form that musically trails off at the end, the sizable transition section between the B and final A sections in the second variation is distinct in the way it layers and interjects echoes of familiar motives. Due to these echoes, the delineation between sectional breaks during the musical transition is somewhat blurry, allowing the choreography to provide section-parsing clues.

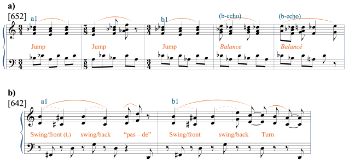

[4.4] The relationship between Bernstein’s music and the waltz topic is complex. The notated meter often does not match the felt, or entrained, meter, and the three-beat waltz is often cut short, a rhythmic effect I term “clipped” rhythm.(43) Example 15a shows this metric play, as the music is not always felt or heard as one might expect from the meter as notated. As I indicate with blue slurs, the repeated “waltz” motives are heard in roughly three-beat groups, although some overlap the notated barlines. The slur line over the

[4.5] In the first three measures, the choreography playfully corresponds to music at some, but not all, of the musical levels. The larger, two-bar musical phrase that reaches over the barline is confirmed by the dancing, while the smaller, internal waltz topic is not. The second sailor’s movement is quite repetitive; the first four dance phrases begin with the same steps. These steps confirm larger musical phrases that keep increasing in length, yet the smaller “waltz” three-groupings (including clipped rhythms) are not always corroborated by the movements. Example 15b redraws the barlines to reveal the chorographic phrases, each consecutive one growing in length: observe the eighth-note groups of 11, 12, 15, and 18.(44) Solid orange slurs show middle-level choreographic subphrases, and dotted orange slurs show smaller groups of steps. Note also how ascending and descending contours in the bass line support the first two phrase groups, before fragmentation increases the intensity.

Example 15a. Mvt. VI.2, mm. 642–652 meter as notated (click to enlarge and listen) | Example 15b. Mvt. VI.2, mm. 642–652, barlines redrawn to explicate choreographic phrases (click to enlarge) |

[4.6] The first three choreographic phrases (a1–b1–a2) feature steps grouped in two-quarter-beat pairs that contradict the musical “waltz” idea—which is not confirmed until the b-echoes. The pendulum motions of the sailor’s front to back leg-swings gently accent groupings of two quarter-notes. The phrases end with either a common back-side-front ballet step called a pas de bourrée or an outside turn. The fourth phrase, three b-echoes in

Example 16. Mvt. VI.2, a1 at m. 652 compared to m. 642, groups of 3 or 2

(click to enlarge and watch in new tab)

[4.7] In the next section, although the music repeats, the choreography is completely different; this time it does contribute to a “waltz” feel.(46) As shown in Example 16a, the first quarter note of each roughly three-beat grouping coincides with the apex of a leap or the beginning of a typical three-step waltz movement (termed a balancé, with down-up-down motions). Even during the clipped rhythm of the

[4.8] The majority of the second variation features elegant steps that are seamlessly linked together, matching how the musical phrases are elided into each other. The dancer’s body is open, and his limbs sweep the air with many slow and long extensions (developés). The frequent choreographic repetition throughout the number makes the times when the steps are changed stand out all the more. Even in the

[4.9] During the last A section (mm. 716–36), the music’s final repeat features a more elongated feel, which is matched by languid, fluid dancing from the sailor. Many steps are similar to the second time through (mm. 668–81), but with wider lunges, expanded arm reaches, and curving turns to emphasize musical curlicues and high notes. The musical phrasing is complemented by flowing dancing without sharp accents. These dance steps include smooth turns with gently bent legs, an unusual off-kilter turn, gently sauntering strides over to the females at the table, and a final graceful slide as he unfurls down to the ground. Even the sailor’s last pose is reserved and sweet: as he ends on the ground in a small arabesque push-up, he gazes and smiles at the females with his head resting on his hands.(47)

[4.10] Overall, in the second variation the music and choreography together establish the character of a cool, easygoing man, who can perform complicated steps to changing musical meters in an effortless manner. The choreography puckishly brings out different elements in the highly repetitive music as different step sequences alternately highlight either the musical motives or the notated meter. The easygoing and romantic waltz topic, while often clipped musically, is “felt” in the music and confirmed by the choreography as the dancer’s moves smooth over the shifts of the notated meter.(48) Taken together, the unbroken chain of rolling turns and mellifluous steps that supplely merge one onto the other interlace with the almost “waltz” meter in the music to create the sweet and playful characterization of the second sailor.

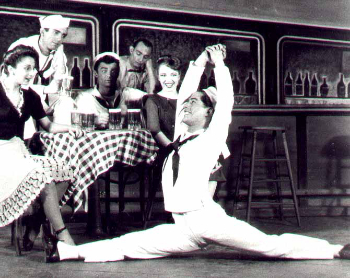

5. Musical and Choreomusical Analysis, Variation 3: “Danzon”

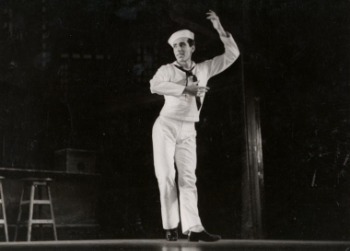

Example 17. Jerome Robbins (Sailor Three) in Fancy Free

(click to enlarge and see the rest)

[5.1] Turning now to the third and last variation, we find a portrayal of the group’s suave leader. This solo number exhibits the strongest corroboration between music and steps in the three variations—the choreography accents the Latin-inspired rhythms in the music, and together they project a compelling and confident character. Sailor Three was originally danced by Robbins himself and he can be seen doing so in archival footage at the New York Public Library. Example 17 shows poses from a signature, hip-accentuating move (Fehl 1944c and 1944d). This “Danzon” was an initial foray into the Latin rhythms for which both Bernstein and Robbins would become very well known, most notably in the next decade when adapted to great success in the musical West Side Story.(49) The third variation has an important place in the ballet, as it is the last of the three solos and leads to the ballet’s climatic ending. It excels in its own way, in part because of the seamless way the music and the choreography work together.

Example 18. Bernstein, “rhumba with a small r”

(click to enlarge)

[5.2] While Jowitt (2004, 85) calls the variation the most “rhythmically sophisticated” of the three, on the surface it is the most metrically simple: it has

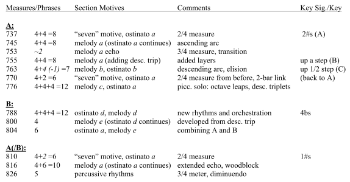

Example 19. Mvt. VI.3, overall formal layout: phrases, repeating themes

(click to enlarge and listen)

[5.3] The overall formal layout of the variation shown in Example 19 indicates phrase lengths, hypermetric groupings, and comments on the motivic material. The variation creates momentum by developing and overlapping familiar rhythms and melodic themes. These include what I call the “seven” motive, because of its elided seven half-note beats; rhythmic ostinatos a and d; and the melodic themes a (ascending melodic arc), b (descending melodic arc), c (octave leaps and descending triplets), d (squarely in

Example 20. Mvt VI.3, mm. 763–767, melody b over syncopated 332 ostinato a

(click to enlarge and listen)

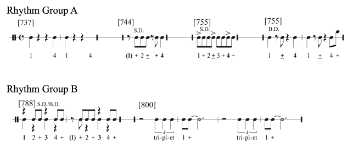

Example 21. Rhythmic Motives: Group A vs. Group B

(click to enlarge and listen)

[5.4] The musical excerpt heard and shown in Example 20 is an illustration of internal syncopated rhythms: a 3-3-2 ostinato a in the bassoon bubbles underneath the more square melodic phrases on top (melody b). This type of syncopated rhythmic pattern—often accompanied with an initial focus on beats one and four—underlies much of the variation. Example 21 shows how the rhythmic feel varies in the different larger sections. The first part of the example, Rhythm Group A, encapsulates the main rhythms in the outer A sections. The common 3-3-2 rumba division often causes a syncopated accent on the “+” of beat two (shown underlined). Later variants in the snare drum and bass drum (S.D./B.D.) also accent similar rhythms. Bernstein uses contrasting, less syncopated rhythms to underlie the middle B section, accompanied with a strong change in orchestration.(51) Shown as Rhythmic Group B, the core ostinato places strong, square accents on beats one and three, while the second and fourth beats are evenly divided (1 2+ 3 4+). In the transition to the final A section, rhythmic groups A & B are layered simultaneously. These add rhythmic complexities into the simple metric context, intricacies that are substantiated by choreographic details.

[5.5] Robbins displays an acute musical sensibility in this variation in the way he fits his smooth choreography to the main rhythmic motives. Not merely matching dance steps to musical notes, Robbins thematically links choreographic space to Bernstein’s musical space. At certain times, physical pauses coincide with musical rests and silence; at other times, music and dance separately generate areas of space, a concept they both share. Musical space offers the dancer places to fill with physical manifestations of the sailor’s character, be they smiles, winks, or seductive poses.

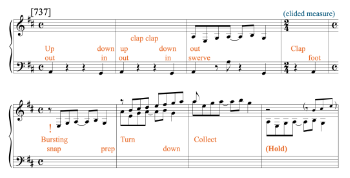

Example 22. Mvt. VI.3, mm. 737–744, choreography for “seven motive”

(click to enlarge and watch)

[5.6] The third variation also features the greatest use of body percussion, a movement style embedded in the motivic sequence of steps that repeats along with the “seven motive” three times; the first presentation begins the variation (mm.737–44). The first few notes of Example 22 show this sequence of quarter notes and rests and the choreography that corresponds with them. The onset of the first musical accent is accompanied with a choreographic accent; the sailor’s legs and arms sharply slide wide apart with palms facing to the back. His feet then go together for a preparatory knee bend (plié); then the legs again accent “out” while his arms reach up high above his head. The musical space of quarter rests in the second measure is accented with postured claps (a body percussion reminiscent of some Flamenco dances). The wavy eighth-note melodic motion in m. 739 is complemented by an undulating physical motion: the sailor’s feet are stationary as his bent knees swerve from one side to the other.

[5.7] The most striking marriage of music and dance occurs on beat one of the motivically elided

[5.8] Example 22 provides a case of choreographic space that contrasts with steady musical motion. In the last two measures shown, the dancer takes four beats to straighten up and collect his arms into his center; this is followed by four beats of movement cessation as he holds, breathes, and lies in wait for his upcoming hip-swivel section. This pose is seemingly motionless, yet holds the latent power of imminent, expected movement. As musical rests can provide space for dance, here, dance, in return, allows space for music. The clip of this excerpt allows one to see how the choreography matches the notes and rests, the music and dance entwining and giving each other space as together they create a unique portrayal of the sailors’ confident leader.

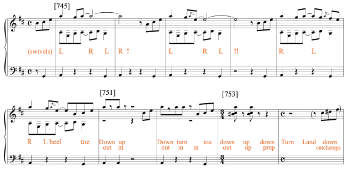

Example 23. Mvt. VI,3, mm. 745–754, swivel section, down/out accents

(click to enlarge and watch)

[5.9] The section that follows explores its own version of choreographic space as it matches the music by alternating choreographed motion and pauses. The two flutes’ sinuous melody evokes swiveling hips from the sailor (Example 23). The dancer’s movements create accents with left and right hip swivels (L, R) that match the syncopated accents in the clarinet and bassoon pitches, and subsequent suspensions of movement match the musical rests. In the first phrase, swivels to the L - R, L, R! are followed by three beats of movement cessation (!). The second phrase begins the same way, but the pausing rest begins earlier with a full beat of choreographic holds: the movements occur on beats 1-34 1--- |1-34 ----| (the video portion of Example 23 includes both examples shown in this section; the beginning “seven motive”; the

Example 24. Mvt. VI.3, mm. 820–830, with final Body Percussion

(click to enlarge and watch)

[5.10] While including some familiar movements, the choreography of the final section further develops these recognizable steps and features the most pronounced use of body percussion. Instead of big leaps or traveling around the stage as in a typical finale section, the ending choreography highlights isolated and controlled movements. As seen in Example 24, the body percussion leads to the climax to emphasize the coolly confident character of the third sailor. He taps on stools with alternating hands, then sits on a barstool (on the downbeat) to tap on the bar with his upstage hand. He next climbs up on the stool and slaps his thighs. The second foot joins on the stool so he can stand up on top; with head lifted slightly back, he pounds proudly on his chest. For the climax, he leaps high off the barstool, clapping in mid-air before he lands on the ground for his final pose on one knee.

Example 25. Jerome Robbins in Fancy Free

(click to enlarge)

[5.11] The rhythmic motions provide an exciting close to the character-filled variation. Indeed, it seems the females watching from the table appreciate this sailor’s solo the most. Set to Robbins’s individual strengths as a dancer as well as choreographer, the third sailor’s musicality and use of space combine with sultry and rhythmic music to create a strong character for the group’s leader (Example 25, [unknown artist] 1944b).

Closing

[6.1] In each of the three solo variations, the music and choreography combine to create a distinct personality for each dancing sailor: acrobatic and flashy for Sailor One, coy and playful for Sailor Two, and suave and controlled for Sailor Three. The individual characterizations in the variations, emerging directly out of the matchless way the dance and music work together, likely helped make Fancy Free the hit that it became. Reviews from the initial production indicate that the three solos were the highlight of the entire ballet. New York Times critic John Martin described the variations this way:

The kids who dance it dance it like mad. Robbins has devised a solo for Harold Lang in which he is called upon to do everything but climb the asbestos curtain. At this point some of us wiseacres began to shake our heads. This was only the first of three solos, and it seemed impossible for the other two boys to do anything that would not look sick by comparison. But Robbins knew what he was about. For John Kriza and himself he designed dances that leaned not on technical stunts but made their points on characterization and individuality of style. (Martin 1944a)

[6.2] Other reviewers agreed with Martin, noting the variations as particularly effective standout moments.(52) Later that year, Martin recognized Robbins as the year’s most outstanding debutante, noting how in Robbins’s choreography, “his people emerge with lives and wills of their own” (1944b, 172). In doing so, Martin again highlighted the individual characters provided by the choreography in the variations. I have shown in detail how the highly individualized music and choreography work together in different ways for each of the three variations.

[6.3] As this article demonstrates, choreomusical analysis helps show how the intertwining of music and dance can create different characterizations. It is not only through correspondence of music and dance, but also by conflict and counterpoint between them, that the characterizations emerge. These nuanced observations are made possible by taking each art form as a subject for detailed investigation—both independently and together. Choreomusical analysis provides a lens through which we can explore the essential and expressive relationship between music and dance and is essential for a thorough understanding of entrainment of movement designed for specific music. While particularly appropriate to the metric dissonance in Bernstein’s musical language,(53) this approach has further applications outside of ballet: film music and staged operas, music videos and TikTok choreography, and synchronized rhythmically flashing lights at a concert (see Lucas 2021). Other musical experiences merge auditory events with visual movement that is not carefully crafted and prescribed, and modified analytical methods can help explore those situations. Our bodies are involved in encountering music, particularly as we experience rhythm and meter, and multifaceted analyses can help us understand how.

Rachel Short

Shenandoah University

1460 University Drive

Winchester, VA 22601

rshort@su.edu

Works Cited

Abrahams, Rosa. 2020. “Mimicry as Movement Analysis.” Analytical Approaches to World Music 7 (2).

Alm, Irene. 1989. “Stravinsky, Balanchine, and Agon: An Analysis Based on the Collaborative Process.” The Journal of Musicology 7 (2): 254–69. https://doi.org/10.2307/763771.

Amberg, George. 1949. Ballet in America, the Emergence of an American Art. Duell, Sloan and Pearce.

Baber, Katherine A. 2019. Leonard Bernstein and the Language of Jazz. University of Illinois Press. https://doi.org/10.5622/illinois/9780252042379.001.0001.

Banes, Sally. 1998. Dancing Women: Female Bodies Onstage. Routledge.

Bell, Matthew. 2021. “Danses Fantastiques: Metrical Dissonance in the Ballet Music of P. I. Tchaikovsky.” Journal of Music Theory 65 (1): 107–37. https://doi.org/10.1215/00222909-9124750.

Bernstein, Leonard. [1939] 1982. “The absorption of race elements into American music” [Harvard bachelor’s thesis], in Findings. 1st ed. Simon & Schuster, pp. 36–99.

—————. 1968. Fancy Free: Ballet. Amberson Enterprises; G. Schirmer.

Biamonte, Nicole. 2014. “Formal Functions of Metric Dissonance in Rock Music.” Music Theory Online 20 (2). https://doi.org/10.30535/mto.20.2.1.

—————. 2008. “Bernstein’s Senior Thesis At Harvard: The Roots of a Lifelong Search to Discover an American Identity.” College Music Symposium 48 (October): 52–68. https://symposium.music.org/48/item/2247-bernsteins-senior-thesis-at-harvard-the-roots-of-a-lifelong-search-to-discover-an-american-identity.html.

Block, Geoffrey. 2009. Enchanted Evenings: The Broadway Musical from Show Boat to Sondheim. 2nd ed. Oxford University Press.

Brower, Candace. 1993. “Memory and the Perception of Rhythm.” Music Theory Spectrum 15 (1): 19–35. https://doi.org/10.2307/745907.

Butler, Mark J. 2001. “Turning the Beat Around: Reinterpretation, Metrical Dissonance, and Asymmetry in Electronic Dance Music.” Music Theory Online 7 (6). https://doi.org/10.30535/mto.7.6.1.

—————. 2006. Unlocking the Groove: Rhythm, Meter, and Musical Design in Electronic Dance Music. Indiana University Press.

Cassidy, Claudia. 1944. “Ballet Is Off to Fast Start on ‘Fancy Free.’” Chicago Daily Tribune (1923–1963), November 25, 1944.

Cohn, Richard. 2021. “Prefatory Note: How Music Theorists Model Time.” Journal of Music Theory 65 (1): 11–16. https://doi.org/10.1215/00222909-9124702.

Combes, Kathleen Breen, dir. 2018. DANCER INSIGHT | Kathleen Breen Combes on Fancy Free. YouTube video, 01:49. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nTWB24xMDOQ.

Cone, Edward T. 1968. Musical Form and Musical Performance. W. W. Norton.

Conrad, Christine. 2000. Jerome Robbins: That Broadway Man, That Ballet Man. Booth-Clibborn Editions.

Cook, Nicholas. 1998. Analysing Musical Multimedia. Clarendon Press; Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780198165897.001.0001.

Cooper, Grosvenor, and Leonard B. Meyer. 1960. The Rhythmic Structure of Music. University of Chicago Press.

Cox, Arnie. 2011. “Embodying Music: Principles of the Mimetic Hypothesis.” Music Theory Online 17 (2). https://doi.org/10.30535/mto.17.2.1.

—————. 2016. Music and Embodied Cognition: Listening, Moving, Feeling, and Thinking. Indiana University Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt200610s.

Damsholt, Inger. 2006. “Mark Morris, Mickey Mouse, and Choreomusical Polemic.” The Opera Quarterly 22 (1): 4–21. https://doi.org/10.1093/oq/kbi119.

Davison, Annette. 2003. “Music and Multimedia: Theory and History.” Music Analysis 22 (3): 341–65. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0262-5245.2003.00189.x.

Denby, Edwin. 1986. Dance Writings. 1st ed. Knopf.

—————. 1998. Dance Writings and Poetry. Edited by Robert Cornfield. Yale University Press.

Eitan, Zohar, and Roni Y. Granot. 2006. “How Music Moves: Musical Parameters and Listeners’ Images of Motion.” Music Perception 23 (3): 221–48. https://doi.org/10.1525/mp.2006.23.3.221.

Foster, Susan Leigh. 1988. Reading Dancing: Bodies and Subjects in Contemporary American Dance. University of California Press. https://doi.org/10.1525/9780520908802.

—————. 1996. Choreography & Narrative: Ballet’s Staging of Story and Desire. Indiana University Press.

Garcia, David F. 2017. Listening for Africa: Freedom, Modernity, and the Logic of Black Music’s African Origins. Duke University Press. https://doi.org/10.1515/9780822373117.

Gjerdingen, Robert. 1989. “Meter as a Mode of Attending: A Network Simulation of Attentional Rhythmicity in Music.” Intégral 3: 67–91.

Gottlieb, Robert, ed. 2008. Reading Dance: A Gathering of Memoirs, Reportage, Criticism, Profiles, Interviews, and Some Uncategorizable Extras. New York: Pantheon.

Gradante, William, and Deane L. Root. 2001. “Rumba.” In Grove Music Online. https://doi.org/10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.24135.

Gradante, William, and Jan Fairley. 2001. “Danzón.” In Grove Music Online. https://doi.org/10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.07204.

Guttman, Sharon E., Lee A. Gilroy, and Randolph Blake. 2005. “Hearing What the Eyes See: Auditory Encoding of Visual Temporal Sequences.” Psychological Science 16 (3): 228–35. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0956-7976.2005.00808.x.

Hasty, Christopher. 1997. Meter As Rhythm. Oxford University Press.

—————. 1999. “Just in Time for More Dichotomies—A Hasty Response.” Music Theory Spectrum 21 (2): 275–93. https://doi.org/10.2307/745865.

Hodgins, Paul. 1991. “Making Sense of the Dance-Music Partnership: A Paradigm for Choreomusical Analysis.” International Guild of Musicians in Dance Journal 1: 38–41.

—————. 1992. Relationships between Score and Choreography in Twentieth-Century Dance: Music, Movement, and Metaphor. E. Mellen Press.

Homans, Jennifer. 2011. Apollo’s Angels: A History of Ballet. New York: Random House.

Horlacher, Gretchen. 2001. “Bartók’s ‘Change of Time’: Coming Unfixed.” Music Theory Online 7 (1). https://doi.org/10.30535/mto.7.1.1.

—————. 2011. Building Blocks: Repetition and Continuity in the Music of Stravinsky. Oxford University Press.

—————. 2018. “Stepping Out: Hearing Balanchine.” Music Theory Online 24 (1). https://doi.org/10.30535/mto.24.1.5.

Jordan, Stephanie. 1993a. “Agon: A Musical/Choreographic Analysis.” Dance Research Journal 25 (2): 1ndash;12. https://doi.org/10.2307/1478549.

—————. 1993b. “Music Puts a Time Corset on the Dance.” Dance Chronicle 16 (3): 295–321. https://doi.org/10.1080/01472529308569137.

—————. 1996. “Musical/Choreographic Discourse: Method, Music Theory, and Meaning.” In Moving Words: Re-Writing Dance, ed. Gay Morris, 15–28. Routledge.

—————. 2000. Moving Music: Dialogues with Music in Twentieth-Century Ballet. Dance Books.

—————. 2007. Stravinsky Dances: Re-Visions across a Century. Dance Books.

—————. 2010. Music Dances: Balanchine Choreographs Stravinsky. George Balanchine Foundation.

—————. 2011. “Choreomusical Conversations: Facing a Double Challenge.” Dance Research Journal 43 (1): 43–64. https://doi.org/10.5406/danceresearchj.43.1.0043.

—————. 2015. Mark Morris: Musician-Choreographer. Alton: Dance Books.

—————. 2021. Introduction. Journal of Music Theory, 65(1), 3–9. https://doi.org/10.1215/00222909-9124690.

Jowitt, Deborah. 2004. Jerome Robbins: His Life, His Theater, His Dance. Simon & Schuster.

Juchniewicz, Jay. 2008. “The Influence of Physical Movement on the Perception of Musical Performance.” Psychology of Music 36 (4): 417–27. https://doi.org/10.1177/0305735607086046.

Knowles, Kristina. 2020. “’No Doubt They Are Dream-Images’: Meter and Memory in George Crumb’s Dream Images from Makrokosmos Volume 1.” GMTH Proceedings 2015, ed. Marcus Aydintan, Florian Edler, Roger Graybill, and Laura Krämer. Hildesheim, Zürich, New York: Georg Olms Verlag, 238–48. https://doi.org/10.31751/p.187.

—————. 2022. “Metric Ambiguity and Rhythmic Gesture in the Works of George Crumb.” Contemporary Music Review 41 (1): 30–54. https://doi.org/10.1080/07494467.2022.2033569.

Krebs, Harald. 1999. Fantasy Pieces: Metrical Dissonance in the Music of Robert Schumann. 1st ed. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195116236.001.0001.

Lamb, Andrew. 2015. “Galop.” Grove Music Online. https://doi.org/10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.10589.

Leaman, Kara Yoo. 2021a. “Dance as Music in George Balanchine’s Concerto Barocco.” SMT-V 7.2. https://doi.org/10.30535/smtv.7.2.

—————. 2021b. “Musical Techniques in Balanchine’s Jazzy Bach Ballet.” Journal of Music Theory 65 (1): 139–69. https://doi.org/10.1215/00222909-9124762.

—————. 2022. “George Balanchine’s Art of Choreographic Musicality in Tschaikovsky Pas de Deux.” Music Theory Spectrum 44 (2): 340–69. https://doi.org/10.1093/mts/mtac007.

Lehman, Frank. 2013. “Hollywood Cadences: Music and the Structure of Cinematic Expectation.” Music Theory Online 19 (4). https://doi.org/10.30535/mto.19.4.2.

Lerdahl, Fred, and Ray S. Jackendoff. 1983. A Generative Theory of Tonal Music. The MIT Press.

Lester, Joel. 1986. The Rhythms of Tonal Music. Southern Illinois University Press.

London, Justin. 1993. “Loud Rests and Other Strange Metric Phenomena (or, Meter as Heard).” Music Theory Online 0 (2). https://doi.org/10.30535/mto.0.2.1.

—————. 1999. “Hasty’s Dichotomy.” Music Theory Spectrum 21 (2): 260–74. https://doi.org/10.2307/745864.

—————. 2010. “Stravinsky’s Hiccups: Cognitive and Aesthetic Aspects of Metrical Ambiguity.” Colloquium talk given at Michigan State University, February 2010.

—————. 2012. Hearing in Time: Psychological Aspects of Musical Meter. 2nd ed. New York: Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199744374.001.0001.

London, Justin, Birgitta Burger, Marc Thompson, and Petri Toiviainen. 2016. “Speed on the Dance Floor: Auditory and Visual Cues for Musical Tempo.” Acta Psychologica 164 (February): 70–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actpsy.2015.12.005.

London, Justin, Tommi Himberg, and Ian Cross. 2009. “The Effect of Structural and Performance Factors in the Perception of Anacruses.” Music Perception 27 (2): 103–20. https://doi.org/10.1525/mp.2009.27.2.103.

Lucas, Olivia R. 2021. “Performing Analysis, Performing Metal: Meshuggah, Edvard Hansson, and the Analytical Light Show.” Music Theory Online 27 (4). https://mtosmt.org/issues/mto.21.27.4/mto.21.27.4.lucas.html.

Malin, Yonatan. 2008. “Metric Analysis and the Metaphor of Energy: A Way into Selected Songs by Wolf and Schoenberg.” Music Theory Spectrum 30 (1): 61–87. https://doi.org/10.1525/mts.2008.30.1.61.

Martin, John. 1944a. “The Dance: ‘Fancy Free’ Does It.” New York Times, April 23, 1944, sec. Drama Recreation News.

—————. 1944b. “Award No. 2: In Recognition of the Year’s Outstanding Debutante—Notes From the Field.” New York Times, June 11, 1944, sec. Drama Recreation News.

Mason, Paul H. 2012. “Music, Dance and the Total Art Work: Choreomusicology in Theory and Practice.” Research in Dance Education 13 (1): 5–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/14647893.2011.651116.

McDonald, Matthew. 2010. “Jeux de Nombres: Automated Rhythm in The Rite of Spring.” Journal of the American Musicological Society 63 (3): 499–551. https://doi.org/10.1525/jams.2010.63.3.499.

McMains, Juliet, and Ben Thomas. 2013. “Translating from Pitch to Plié: Music Theory for Dance Scholars and Close Movement Analysis for Music Scholars.” Dance Chronicle 36 (2): 196–217. https://doi.org/10.1080/01472526.2013.792714.

McMillin, Scott. 2006. The Musical as Drama: A Study of the Principles and Conventions Behind Musical Shows from Kern to Sondheim. Princeton University Press.

Mirka, Danuta. 2009. Metric Manipulations in Haydn and Mozart: Chamber Music for Strings, 1787–1791. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press.

Morris, Gay, ed. 1996. Moving Words: Re-Writing Dance. Routledge.

Pasler, Jann. 1982. “Debussy, ‘Jeux’: Playing with Time and Form.” 19th-Century Music 6 (1): 60–75. https://doi.org/10.2307/746232.

—————. 1986. “Music and Spectacle in Petrushka and The Rite of Spring.” In Confronting Stravinsky: Man, Musician, and Modernist, 53–81. University of California Press. https://doi.org/10.1525/9780520332461-006.

Patty, Austin T. 2009. “Pacing Scenarios: How Harmonic Rhythm and Melodic Pacing Influence Our Experience of Musical Climax.” Music Theory Spectrum 31 (2): 325–67. https://doi.org/10.1525/mts.2009.31.2.325.

Peñalosa, David, and Peter Greenwood. 2009. The Clave Matrix: Afro-Cuban Rhythm: Its Principles and African Origins. Vol. 1 of Unlocking Clave Series. Bembe Books.

Phillips-Silver, Jessica, and Laurel J. Trainor. 2007. “Hearing What the Body Feels: Auditory Encoding of Rhythmic Movement.” Cognition 105 (3): 533–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cognition.2006.11.006.

Read, Jo. 2020. “Animating the Real: Illusions, Musicality and the Live Dancing Body.” The International Journal of Screendance 11 (October). https://doi.org/10.18061/ijsd.v11i0.7100.

Redfern, Sophie. 2021. Bernstein and Robbins: The Early Ballets. Eastman Studies in Music, v. 173. Rochester, NY: University of Rochester Press.

Robbins, Jerome. n.d. “The Jerome Robbins Personal Papers, (S)*MGZMD 182.” Jerome Robbins Dance Division. The New York Public Library for the Performing Arts. Accessed August 14, 2013. https://archives.nypl.org/dan/19855.

Rothstein, William Nathan. 1990. Phrase Rhythm in Tonal Music. New York: Schirmer Books.

Schachter, Carl. 1998. Unfoldings: Essays in Schenkerian Theory and Analysis. Edited by Joseph N. Straus. 1st ed. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780195120134.001.0001.

Short, Rachel. 2023. “Interactions Between Music and Dance in Two Musical Theatre Tap Breaks.” SMT-V 9.3. https://vimeo.com/societymusictheory/smtv093short. http://doi.org/10.30535/smtv.9.3.

Simpson-Litke, Rebecca. 2021. “Flipped, Broken, and Paused Clave: Dancing through Metric Ambiguities in Salsa Music.” Journal of Music Theory 65 (1): 39–80. https://doi.org/10.1215/00222909-9124726.

Simpson-Litke, Rebecca, and Chris Stover. 2019. “Theorizing Fundamental Music/Dance Interactions in Salsa.” Music Theory Spectrum 41 (1): 74–103. https://doi.org/10.1093/mts/mty033.

Sterbenz, Maeve. 2017. “Movement, Music, Feminism: An Analysis of Movement-Music Interactions and the Articulation of Masculinity in Tyler, the Creator’s ‘Yonkers’ Music Video.” Music Theory Online 23 (2). https://doi.org/10.30535/mto.23.2.6.

Stevens, Alison. 2021. “Music in the Body: The Eighteenth-Century Contredanse and Hypermetrical Hearing.” Journal of Music Theory 65 (1): 81–106. https://doi.org/10.1215/00222909-9124738.

Still, Jonathan. 2015. “How Down Is a Downbeat? Feeling Meter and Gravity in Music and Dance.” Empirical Musicology Review 10 (1-2): 121–34. https://doi.org/10.18061/emr.v10i1-2.4577.

Temperley, David. 2008. “Hypermetrical Transitions.” Music Theory Spectrum 30 (2): 305–25. https://doi.org/10.1525/mts.2008.30.2.305.

Tobias, Tobi. 2008. “Bringing Back Robbins’s ‘Fancy.’” In Reading Dance: A Gathering of Memoirs, Reportage, Criticism, Profiles, Interviews, and Some Uncategorizable Extras, ed. Robert Gottlieb, 1141–56. Pantheon.

van den Toorn, Pieter C. 1987. Stravinsky and The Rite of Spring: The Beginnings of a Musical Language. University of California Press.

Vuoskoski, Jonna K., Marc R. Thompson, Charles Spence, and Eric F. Clarke. 2016. “Interaction of Sight and Sound in the Perception and Experience of Musical Performance.” Music Perception 33 (4): 457–71. https://doi.org/10.1525/mp.2016.33.4.457.

Whalen, Cecilia. 2018. “Why We Still Watch ‘Fancy Free.’” Ninertimes, October 17, 2018. https://www.ninertimes.com/arts_and_culture/why-we-still-watch-fancy-free/article_28fcdfed-58a1-5f61-a167-c838e82b1645.html.

White, Barbara. 2006. “‘As If They Didn’t Hear the Music,’ Or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love Mickey Mouse.” The Opera Quarterly 22 (1): 65–89. https://doi.org/10.1093/oq/kbi108.

Yust, Jason. 2018. Organized Time: Rhythm, Tonality, and Form. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780190696481.001.0001.

Zbikowski, Lawrence M. 1998. “Metaphor and Music Theory: Reflections from Cognitive Science.” Music Theory Online 4 (1). https://doi.org/10.30535/mto.4.1.1.

—————. 2005. Conceptualizing Music: Cognitive Structure, Theory, and Analysis. Oxford University Press.

—————. 2009. “Music, Language, and Multimodal Metaphor.” In Multimodal Metaphor, ed. Charles Forceville and Eduardo Urios-Aparisi. Moulton de Gruyter. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110215366.6.359.

Zolotow, Sam. 1945. “Ballet Sets a Record: Robbins7rsquo; ‘Fancy Free’ Performed for 162d Time in a Year.” New York Times, April 19, 1945. https://www.nytimes.com/1945/04/19/archives/ballet-sets-a-record-robbins-fancy-free-performed-for-162d-time-in.html.

Images/Videos Cited

Images/Videos Cited

[unknown artist]. 1944a. “[Portrait of Harold Land, in Fancy Free].” still image. Photograph. Harold Lang Memorial Website. http://harold-lang.com/index.htm, (a href='http://harold-lang.com/ABT_1943_HL/ABT-FF.jpg'>http://harold-lang.com/ABT_1943_HL/ABT-FF.jpg).

[unknown artist]. 1944b. Jerome Robbins in Fancy Free. Still image. Jerome Robbins Dance Division. New York Public Library Digital Collections. https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/fbc73c00-09f0-0136-5872-0f7d9fc6093f.

Bernstein, Leonard. 1986. Fancy Free. With Jerome Robbins, Joseph Duell, Jean-Pierre Frohlich, Kipling Houston, and the New York City Ballet. Video recording on YouTube. TheBalletTapes. https://youtu.be/3Ou-O9Awkzo?si=xyq_7jdpQM0yUtBf&t=1.

Fehl, Fred. 1944a. Harold Lang, John Kriza, and Jerome Robbins in Fancy Free, no 28. Still image. Jerome Robbins Dance Division. New York Public Library Digital Collections. https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/f02a2e80-09f0-0136-59b9-4d929cc1a01e.

—————. 1944b. Harold Lang, John Kriza, and Jerome Robbins in Fancy Free, no 37. Still image. Jerome Robbins Dance Division. New York Public Library Digital Collections. https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/2ffd9190-14e2-0131-c404-58d385a7b928.

—————. 1944c. Jerome Robbins. Still image. Jerome Robbins Dance Division. New York Public Library Digital Collections. https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/044eb0b0-dc84-0136-8709-0549e38c3133.

—————. 1944d. Jerome Robbins, in front of skyline backdrop, no. 207. Still image. Jerome Robbins Dance Division. New York Public Library Digital Collections. https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/8a948900-45a3-0136-8b88-06920feec65c.

Van Vechten, Carl. 1949a. [Portrait of John Kriza, in Fancy Free]. Still image. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs. a href='https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2004663147/'>https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2004663147/.

—————. 1949b. [Portrait of John Kriza, in Fancy Free, Colorized]. Still image. Still image. Jerome Robbins Dance Division. New York Public Library Digital Collections. https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/b580e1f0-e281-0135-d0e8-5f6665417a30.

Footnotes

1. Cook 1998 uses ballet as an example of interaction between two separate elements, music and dance, “and the aesthetic effect of ballet emerges from the interaction between the two.” In addition, McMains and Thomas (2013) explain how related arts can act in amplification of each other. As an example of past scholarship, music theorists have written at length on rhythmic matters in the first few measures of the Rite of Spring; however, they often overlook potential insights provided by broadening the analyses to choreographic aspects of the ballet (see McDonald 2010, van den Toorn 1987, and Pasler 1986). As Pasler describes, the creators of the Rite all worked together in a collaborative process to create a total artwork. While the ballet aspect was disowned by Stravinsky for a time, it was initially written for ballet, as a collaboration between the arts, or synchronization between the senses.

Return to text

2. See Leaman 2021b for an example of “sketch-dancing,” following Jordan’s (2015) “sketch-learning” analyses that invite readers to consider moving along with the choreography. Phillips-Silver and Trainor 2007 explores how rhythmic movement can affect auditory encoding. Sterbenz’s 2017 analytical discoveries hinge on her embodied experiences as she considered “what it might feel like to move as Tyler moves” [46].

Return to text

3. I use the term “choreomusical studies” to refer to the variety of ways scholars approach music and dance, and “choreomusical analysis” to describe a methodology that 1) integrates dance analysis with rhythmic and metric analysis and 2) is based in part on music-theoretical concerns.

Return to text

4. Among the issues Jordan raises is the “fundamental differences in practice and conceptual frameworks” between the disciplines of music and dance (2011, 43). See also McMains and Thomas 2013 for further discussion of the disparity between disciplines.

Return to text

5. For example, Foster (1988; 1996) and Banes (1998) discuss the desire inherent in ballet’s narratives and how onstage female dancing bodies are viewed through the male gaze. Morris (1996) provides further examples of other interests combined with dance scholarship; these include postmodernism and poststructrualism, a focus on the gendered, racialized body, class, and cross-cultural exchanges. As Jordan notes in 2011, “There are relatively few analyses of dances

Return to text

6. Dance researcher Hodgins (1991, 1992) delineates two broad categories of “choreomusical relationships”—intrinsic and extrinsic—and fits sections of ballets into those lists. For him, rhythmic and structural elements fall under the intrinsic relationship category.

Return to text

7. An early example of this is Pasler 1982, which discusses how the dance scenario for the ballet Jeux inspired the rhythmic motives and temporal elements that create formal coherence in Debussy’s music.

Return to text

8. Jordan (1996, 17) argues that dance scholars should include formal analytical structures from music research, because the “particular power of musicology for dance scholars” is a “formalist tradition of analysis to be used or unmasked.” Specifically, Jordan analyzes Humphrey’s Passacaglia and Fugue in C minor, looking at rhythmic counterpoint and hypermetrical incongruence between music and dance, as well as “music visualization” (Humphrey’s term), which she calls “concurrence.”

Return to text

9. In her case studies on Balanchine ballets set to Stravinsky’s music, Leaman’s method is historically grounded in Balanchine’s own aesthetic view. Other scholars have also focused their analytical tools on the Balanchine and Stravinsky partnership, including Jordan (2007), whose close analyses are concerned with the “musical/choreographic connections” that occur when Balanchine’s choreography mirrors Stravinsky’s music. Irene Alm’s 1989 analysis of Agon uses archival evidence to explore the collaborative process between Balanchine and Stravinsky as a way to understand its structure and cohesive unity. See also Horlacher 2018, Jordan 1993a and 1993b, and Jordan 2000.

Return to text

10. See also Simpson-Litke and Stover 2019, which looks at the basic structural connections between salsa music and footwork patterns, using overlaid musical scores to analyze social dance interactions.

Return to text

11. Other potential systems include the flexibility of processual methodologies, as discussed by Horlacher (2001) and Hasty (1997). While Yust (2018) also has a processual exploration of temporal structures, his tonal focus with Schenkerian underpinnings and the related complex hierarchical networks do not align with the aims of this project.

Return to text

12. “Dissonance” refers not to traditional musical dissonances, but conflicts or non-alignments in rhythm and metric patterns. Recent dance scholars who explore similar concepts include Bell 2021, Leaman 2022, and Simpson-Litke 2021.

Return to text

13. London (2012, 22) presumes “that listeners do not normally have access to other, nonauditory information.” While this is true for a general musical listening, the audience of a ballet performance, however, needs to consider more than just the metric audition to aim for a multimodal metric understanding. While London discusses meter primarily from a listeners’ perspective, he also mentions that somehow as a listener we are bodily involved in listening as entrainment “engages our sensorimotor system.” See also Eitan and Granot 2006, who explore “the ways listeners associate changes in musical parameters with physical space and bodily motion” (221); Juchniewicz 2008; and Vuoskoski et al. 2016.

Return to text