Report: My Footsteps and Related Thoughts on the Systematic Construction of Linguistics of Music in the 21st Century*

Qian Rong 錢茸

KEYWORDS: linguistics of music; analysis of the sounds of chàngcí 唱詞; non-conventional methods for notation and analysis; explicit musical signs and implicit musical signs of chàngcí; “yuèshuō 樂說” (speaking in vocal music)

ABSTRACT: This article derives from a speech at the 2019 forum to commemorate the 120th anniversary of Professor Yáng Yīnliú’s birth. It contains two large sections. The first section is a brief report of how, since the beginning of the 21st century, the author has introduced modern linguistics and other non-conventional methods for notation and analysis, taking the analysis of the sounds of chàngcí 唱詞 as the starting point for research, and contributing to the systematic construction of the cross-cutting discipline “linguistics of music” in music institutions. The section also introduces the newly published monograph Exploring Regional Charms Beyond Musical Notes: Analysis of the Sounds of chàngcí (2020), the textbook Foundation of the Linguistics of Music (2018), and the research project “Yuèshuō 樂說 in Chinese Vocal Music” for “Unpopular and Esoteric Projects,” supported by the National Social Science Fund of China (2019). The second section of the article further argues for the need for linguistics of music from three perspectives: the protection and inheritance of intangible cultural heritage, thick description of regional music, and music composition with Chinese elements. The article discusses not only the sounds of words as music but also the issue of phonetic notation in musical scores.

PEER REVIEWER: Jacob Reed

DOI: 10.30535/mto.30.4.14

Copyright © 2024 Society for Music Theory

Introduction(1)

[0.1] Instead of music, I majored in history in my undergraduate study. I worked for several newspapers and magazines on the editorial staff for eleven years before I became a graduate student majoring in musicology on traditional music in China, when I was thirty-eight. I have continued to study and work in this field since then. Although I did not get a chance to listen to Professor Yáng Yīnliú’s 楊蔭瀏 lectures, I benefited very much from reading Professor Yang’s books and articles on traditional music in China.(2) In his article “Initial Exploration into Linguistic Musicology,” Professor Yang solemnly stressed that “the relationship between music and language is a very important research area” (Yang 1983).

[0.2] During my graduate studies and after I started working at the Conservatory at the age of forty, my research objects were, and have been, genres of traditional vocal music in China (folksong, shūochàng 說唱, and xìqǚ 戲曲). The more I studied, the more I realized that the relationship between music and language is a non-negligible object of study. Working on traditional Chinese music year after year had motivated me to develop the field of “linguistics of music”—the cross-cutting discipline concerned with language and music.(4) I realized that this would be an enormous project, a focus deserving of my lifelong commitment. I have seen clearly that in order to establish linguistics of music in music institutions, it is urgently needed to build a systematic structure of the discipline’s concepts, fundamental theory, and teaching-research practices. Therefore, since the beginning of the 21st century, I have started to focus my career on this field. As I systematically studied the related theory of linguistics, I have been working to establish a fundamental theory of linguistics of music and to conduct case studies in this discipline (with several such articles published). In 2008, after these preparations, I started teaching the elective course “Foundations of Linguistics of Music” at the Conservatory.

[0.3] Eventually, I began working on three official projects in linguistics of music and completed two of them. As we are commemorating the 120th anniversary of Professor Yang’s birth, I would like to make a brief report to Professor Yang’s heavenly spirit on two aspects: “Research contents” and “Further examination on the needs of the discipline.”

Section A: Research Contents

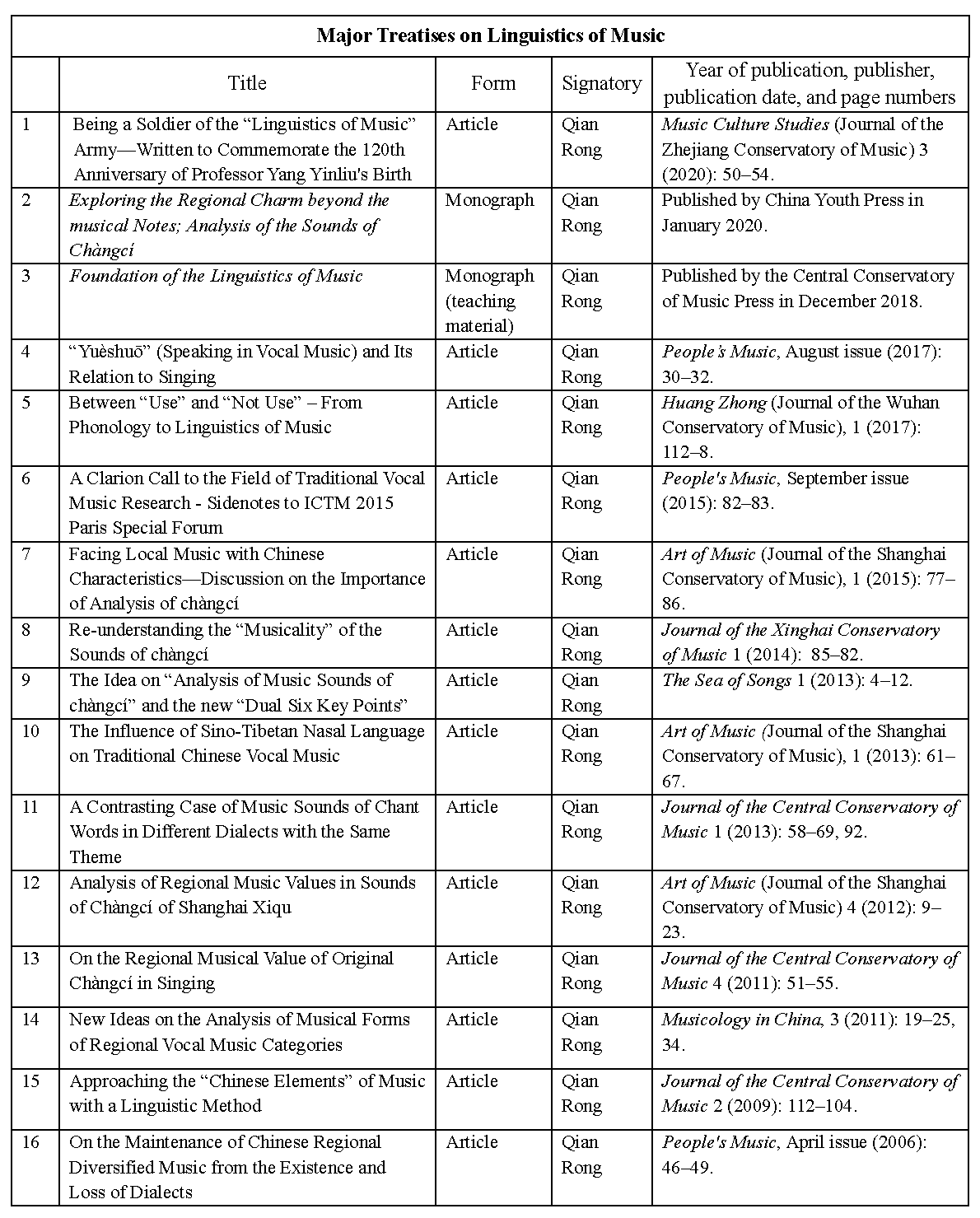

[1.1] The three projects on linguistics of music which I have completed over the years or which are still in progress are:

- The third phase of Project 211 at the Central Conservatory of Music, Foundation of the Linguistics of Music (published by the Central Conservatory of Music Press in December 2018);

- The key project Exploring Regional Charms Beyond the Musical Notes: Analysis of the Sounds of Chàngcí (published by China Youth Press in January 2020);

- An “Unpopular and Esoteric Project” supported by the National Social Science Fund, titled “Yuèshuō in Chinese Vocal Music” (in progress).

[1.2] The specific research contents of these projects, showing the six steps of my research on linguistics of music, can be summarized as follows:

Ⅰ. Naming and Positioning of the Discipline

[1.3] Since this discipline is still budding, its namings in relevant articles are not unified, and its positioning in the entire field of music study is neither mature nor clear. Therefore, there is still room to explore the naming and positioning of the discipline.

(1) On the Naming of the Discipline

[1.4] Both Professor Yáng Yīnliú and Professor Zhāng Míng 張鳴used “語言音樂學” (Linguistic Musicology) as the discipline’s name. Meanwhile, I used “民族語言音樂學” (Ethnolinguistic Musicology) in one of my articles, based on the following considerations. Firstly, the name Ethnolinguistic Musicology is prefixed by “ethno,” which is intended to emphasize the multi-ethnic aspect within vocal musics of multi-ethnic native languages. Secondly, referring to the English version of the discipline as Ethnolinguistic Musicology was approved by Professor Pǔ Shí 蒲實, the expert on music literature. It is consistent with the content and usage of “Ethnomusicology,” as both terms use the prefix “ethno” (anthropological) to emphasize musical cultures of diverse mother tongues, and the subordinate relationship of the former (anthropology) to the latter (musicology).

[1.5] Later, I switched to using “linguistics of music” (音樂語言學) for two reasons. First, the Chinese term “民族” (ethnic) has a certain degree of ambiguity. It might be misunderstood as indicating that the object of study is limited only to vocal musics of ethnic groups in China if the prefix “ethno” is added to the name. In reality, the subject matter of this discipline transcends these bounds. Secondly, according to some scholars, methodology should be at the root of the names of cross-cutting disciplines. In this case, the discipline’s main research method is linguistics, and its object of study is music. Therefore, I followed the English and Chinese naming used in Mr. Alan Merriam’s Anthropology of Music (1964): “linguistics of music” in English, and “音樂語言學” in Chinese.

[1.6] However, “音樂語言學” (linguistics of music) as a Chinese appellation is somehow ambiguous, as many people misunderstand the term “音樂語言” as “musical vocabulary.” Ultimately, after consulting a number of experts, I decided to separate the Chinese and English names of this discipline according to a convention allowed by the translation community. The Chinese name of the discipline extends the idioms of our predecessors, namely “語言音樂學” (Linguistic Musicology), whereas the English name uses “linguistics of music,” intending to be associated with the model of “anthropology of music” when communicating overseas.

(2) The Positioning of the Discipline

[1.7] I position linguistics of music as both a branch of ethnomusicology and of linguistics. It is a systematic, cross-cutting discipline with regional musics as its main research objects. It combines modern linguistic methods (including phonetic, analytical, and speculative methods, as well as various non-conventional methods for notation and analysis, mainly those of digital science and technology) with musicological methods (normally based on study of musical notes).

[1.8] Its research focus comprises (a) the sounds of chàngcí 唱詞 (defined below) as used in the vocal genres of various human groups and their relationship with their tunes, and (b) the relationship between the mother tongue and the music of the relevant region.

[1.9] Linguistics of music is not only an essential fundamental theory for music theorists who analyze multi-regional musics, but also an applied theory for artistic practices such as composition, conducting, and performance of instrumental and vocal music.

Ⅱ. Musical Analysis of the Sounds of chàngcí 唱詞

[1.10] I would like to address the question: why has linguistics of music been marginalized in music studies for so long?

[1.11] I have observed that music scholars (including myself) have for many years held chàngcí 唱詞as mere literary signs within the integrative art of vocal genres.(5) However, I believe that this is a serious misunderstanding. The result of my explorations from the point of view of semiotics is that chàngcí are both literary and musical signs. They have a double identity.

[1.12] Due to the strong literary connotation of “ci詞” (words) in the term “chàngcí 唱詞,” it is easy to think that “ci” (words) have only literary value, and only convey the semantics of literary words. In actuality, the textual signs used in chàngcí already have a certain complexity outside of music works. As long as one is not deaf or mute, human acquisition of words always includes two conditions—the semantic and phonetic. When words enter vocal music to become chàngcí, they not only bring their meanings of the words, but also the sounds of the words when pronounced. More importantly, when words become part of vocal music, these sounds (which I call the sounds of chàngcí) are musical. When viewed as artistic signs, chàngcí cannot be the carrier of a single sign. The semantics conveyed by characters of chàngcí is literary, while the sonic part of chàngcí—including timbre, tone, formal beauty, and many other aspects of words—belong to the musical sign, as they are directly or indirectly involved in the composition of auditory beauty in vocal works.

[1.13] Based on the above considerations, I conclude that the focus of linguistics of music is on the sounds of chàngcí” as musical signs, rather than chàngcí broadly construed. Therefore, linguistics of music should certainly be qualified to exist in music institutions, and to belong within the purview of musicians.

Ⅲ. The Musical Value of the Sounds of chàngcí themselves and the “Dual Six Key Points”

[1.14] Another cognitive misconception in music studies is that in the past, chàngcí was only discussed as having mere “influence” on music. Our Sino-Tibetan language family is a tonal language, and the fluctuation of the tone of speech inevitably affects the generation of chàngqiāng 唱腔 (vocal melodies of any genre). Of course, this aspect of the relationship between chàngcí and chàngqiāng is most easily captured. However, if further questioned, does chàngcí only have an “influence” on vocal musics?

[1.15] When I separated the sounds of chàngcí as musical signs from the broadly construed chàngcí, I naturally discovered another fact that had been overlooked by musical circles for a long time. That is, the sounds of chàngcí themselves not only have their own musicality (their own sound forms, including tone, timbre, duration, formal beauty, etc.), but also have an “influence” on the chàngqiāng. In other words, the sounds of chàngcí themselves are of the most fundamental musical value, and have long been overlooked in musical circles.

Example 1

(click to enlarge)

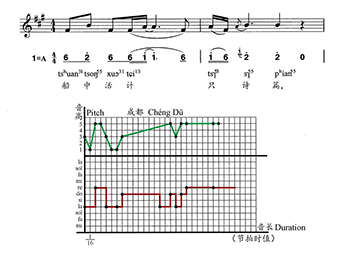

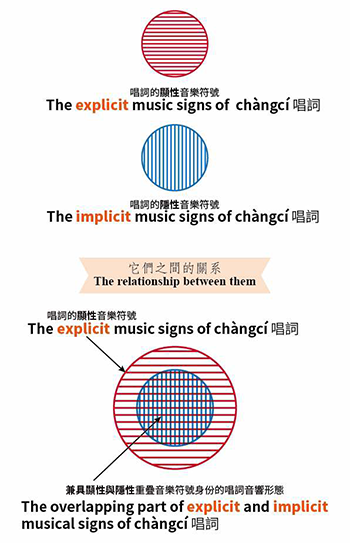

[1.16] I have also theorized that the sounds of chàngcí contain two types of musical signs: those which only indicate the explicit musical value (the form of the sounds of chàngcí themselves) are explicit musical signs, and those which influence the melody are implicit musical signs. For instance, let us discuss Example 1.(6)

Example 2

(click to enlarge)

[1.17] The International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA) above each character in this chàngcí displays the intonation of the chàngcí, which is a part of the phonetic form and is an explicit musical sign. The pitch trend chart shows the comparison between the tone of the chàngcí and the pitch trend of the chàngqiāng. The consistency of the overall trend indicates that the tone of the chàngcí has a significant impact on the melody, demonstrating the implicit influence of the tone of the chàngcí on the chàngqiāng. The reason why it is called “implicit&rdqduo; is because this influence is not precise and is only an approximation. The sounds of chàngcí that have value as implicit musical signs must first have an explicit value (their own sound form), meaning that implicit musical signs must have two types of musical value (Example 2).(7)

[1.18] Following the above thinking, I have summarized six key points each for explicit and implicit music signs of chàngcí in my exploration of regional vocal musics. Since both happen to be six key points, I call these the Dual Six Key Points.(8) These are not fixed patterns, but merely points of inspiration to help students analyze regional vocal musics using linguistics of music.

[1.19] The Six Key Points of explicit musical signs in chàngcí are:

- dàibiǎoxìng dìyù yīnshēng xuǎndiǎn 代表性地域音聲選點 (Characteristic regional phonetics)

- sècǎi dùilì xuǎndiǎn色彩對立選點 (Opposition of regional sonic colors)

- dìyùxìng chènzì xuǎndiǎn地域性襯字選點 (Regional padding words)

- rèntóng húigūi héxié xuǎndiǎn認同回歸和諧選點 (Identification of regression and harmony)

- dìyù shēngyuè pínzhǒng zhuānyòng yīnshēng xuǎndiǎn地域聲樂品種專用音聲選點 (Special vocal sounds for regional vocal genres)

- dǎoyǐng tèsè shēngyuè fāshēng xuǎndiǎn導引特色聲樂發聲選點 (Guiding distinctive modes of vocal production)

[1.20] The Six Key Points of implicit musical signs in chàngcí are:

- dìyùxìng chàngcí zìdiào zǒuxiàng dùi chàngqiāng xuánlǜ dè yǐngxiǎng 地域性唱詞字調走向對唱腔旋律的影響 (The influence of tonal trajectories in regional chàngcí on chàngqiāng)

- dìyùxìng chàngcí xíguànxìng jùdiào dùi chàngqiāng xuánlǜ dè yǐngxiǎng 地域性唱詞習慣性句調對唱腔旋律的影響 (The influence of conventional sentences in regional chàngcí on chàngqiāng)

- chàngcí zìliang jí jiégòu biànhuà dùi chàngqiāng dè yǐngxiǎng 唱詞字量及結構變化對唱腔的影響 (The influence of changes in syllabic count or syntactic structure in chàngcí on chàngqiāng)

- dìyùxìng chàngcí yīnsè dùi chàngqiāng xuánlǜ dè yǐngxiǎng 地域性唱詞音色對唱腔旋律的影響 (The influence of timbre in regional chàngcí on chàngqiāng)

- dìyùxìng chàngcí yīnshēng chángduǎn dùi chàngqiāng xuánlǜ dè yǐng xiǎng 地域性唱詞音聲長短對唱腔旋律的影響 (The influence of duration of music sound in chàngcí on chàngqiāng)

- dìyùxìng chàngcí xíguànxìng zhòngyīn dùi chàngqiāng xuánlǜ dè yǐngxiǎng 地域性唱詞習慣性重音對唱腔旋律的影響 (The influence of stress conventions in regional chàngcí on chàngqiāng)

Ⅳ. The Five Aspects of Core Cognition of Non-Conventional Methods for Notation and Analysis

[1.21] There is another deep reason for linguistics of music being marginalized in musical circles. Being influenced by the existing institutional education, musicians have been taking the methods of analyzing musical notes as the mainstream of music analysis and ignoring the relationship between vocal musics and language. Mainstream research has furthermore ignored the sheer regional diversity of these entangled vocal musics and languages. Taking again the perspective of regional vocal music research, I have proposed that there are at least five aspects to this research. Within these aspects, the function of non-conventional methods for notation and analysis (methods from linguistics of music) should be no less significant than conventional methods for musical signs. Instead, both should become core epistemological practices.

[1.22] The five aspects are:

- Tracing the source of “xiangyun 鄉韻” (regional musical charm);

- Sonic analysis of chàngcí;

- Phonetic analysis of chàngcí;

- Analysis of what I call the double “bridges” of chàngcí—whereby their sounds are not only a “bridge” between musical works and culture in general, but also a “bridge” between language and music;

- Analysis of the sounds of “yùeshūo 樂說” (see part VI below).

[1.23] My aim in emphasizing these core epistemological functions and investigative non-conventional methods for notation and analysis is merely to advocate for their rightful position in our analytical toolkit. I have absolutely no intention to deny the value of conventional recording and description methods.

Ⅴ. Promoting “Shuāngyīn Vocal Notation 雙音唱譜”

[1.23] In conventional vocal notation, notes are symbols indicating the pitches of the chàngqiāng, while the chàngcí (in non-phonetic script) indicate semantics only. I know that in the vocal musical practice of some western countries, when singing songs of different languages, there are international phonetic symbols below the notes on the score. I refer to this type of score as “shuāngyīn Vocal Notation 雙音唱譜 (Double-Tone Notation),” which includes both musical notes and words plus IPA.

[1.24] IPA is a universal alphabetic system for phonetic notation. Its first draft was completed by the French linguist Paul Passy in 1888 and commissioned by the International Phonetic Association (established in London in 1886). Thereafter, it has been constantly revised and refined by the International Phonetic Association for more than a hundred years. Nowadays, it is commonly accepted as the most scientific symbolic system for recording speech to date, and has become the foundational and iconic system of modern phonetics. Therefore, using shuāngyīn Vocal Notation not only allows the sounds of chàngcí to be notated for non-phonetic scripts, but also puts both the chàngqīang and the chàngcí in the form of a universally recognized symbolic system. Thus, to conduct “sonic analysis of chàngcí,” I advocate the use of shuāngyīn Vocal Notation.

[1.25] A question arises here, concerning the attitude towards the relationship between taking imported goods and maintaining one’s own-cultural characteristics. In my opinion, a person in contemporary society should neither worship foreign dominant cultures, nor absolutely reject foreign cultures and keep them outside the country. “Localization” was originally proposed as a slogan aimed to fight against the blind use of foreign culture and to advocate for the preservation of one’s own cultural characteristics. Foreign cultural products are not conducive to this goal, so we should naturally put them in an appropriate position to avoid their excessive impact on and replacement of local cultural characteristics. On the other hand, when a foreign cultural product is conducive to the preservation of our local multi-cultural characteristics, why not put the foreign concept into practice?

Ⅵ. The Research on “yuèshuō 樂說”

[1.26] “Yuèshuō 樂說” (literally “musical speech”) refers to speaking within traditional Chinese vocal musics. In order to distinguish yuèshuō from the word “shuō說” (literally, “speech,” the linguistic term used to describe language communication behavior), and also to emphasize its musical properties, we call it yuèshuō. This concept covers all vocal sounds that differ from strict “singing” due to being recitative in style, such as various “shūo 說,” “bái 白,” “sòng 誦,” “yīng 吟” and other speaking sounds (which staff notation cannot accurately label) in vocal passages. In my opinion, yuèshuō and “singing” should be on equal footing in vocal musics. Yuèshuō is another form of musical expression.

[1.27] In May 2015, I was recommended by Xiāo Méi 蕭梅, China Director of International Council for Traditions of Music and Dance (ICTM), to attend the Paris Forum, “Between Speech and Song: Liminal Utterances,” as the only speaker from China. The revised Chinese draft, “Attempt to Analyze Yuèshuō and Its Relationship with Singing,” was published in the journal People’s Music in August 2017. In 2019, my follow-up research project “Yuèshuō in Chinese Vocal Music” was selected for funding as a part of the “Unpopular and Esoteric Projects” program of the National Social Science Fund.(9)

[1.28] Considering the tangled relationship between language and music in China, the richness of the topolects of China’s ethnic groups, the multiple levels of “yuèshuō” in vocal genres of various regions, and the various synergies, reflections, and transformations between yuèshuō and “singing,” etc., the prospects in linguistics of music for an exploration of yuèshuō are even broader than those of the “sounds of chàngcí.”

Section B: Further Examination on the Needs of the Discipline

[2.1] The process of cultivating the field of linguistics of music has made me increasingly aware of the many specific links between Chinese languages and Chinese musics. As a result, I have grown conscientious of the multi-faceted demands that music studies places upon the linguistics of music. At the least, those demands include the following three:

Ⅰ. The Need for the Protection and Inheritance of Intangible Cultural Heritage

[2.2] UNESCO launched the “Protection and Inheritance of Intangible Cultural Heritage” project at the beginning of the 21st century. Its goal is to protect the intangible cultures of all people groups in order to maintain the multicultural landscape of humanity. The focus of the “Protection and Inheritance of Intangible Cultural Heritage” project in the field of music is, of course, the maintenance of the characteristics of various ethnic groups and various regional music cultures. One of the most prominent features of traditional Chinese music is regionalism, which refers to the use of native chàngcí (local dialects or ethnic languages) in ethnic and regional singing genres. In other words, the native chàngcí in these indigenous singing genres undoubtedly carry a rich regional vocal gene. Whether we can fully record their true phonetic morphology will inevitably affect the effectiveness of preservation and inheritance.

[2.3] Audio and video recordings are good ways to preserve the entirety of works, but from the perspective of inheritance, symbolic recording is undoubtedly a more convenient means of transmission. To record the pitch information of tunes, musical notes can certainly be used, but the sound patterns of native chàngcí often cannot be marked by musical notes alone. Even pinyin, the Chinese phonetic writing system, cannot fully capture those sounds. This is because pinyin was developed to promote Mandarin, and the phonemes of Mandarin are limited. The number of symbols in pinyin is correspondingly limited and cannot cover the phonemes of all topolects and regions. Although some ethnic groups’ native phonetic symbols do duly represent the chàngcí within their own ethnic groups, these notation systems are not universally recognized. This is bound to be detrimental to the project of cultural transmission, especially given the international capacity at which music institutions operate, where students may be from all over the world.

[2.4] Therefore, it is evident that the “Protection and Inheritance of Intangible Cultural Heritage” is calling for a means of representing non-musical notes in linguistics of music.

Ⅱ. The Need for “Thick Description” of Regional Music

[2.5] At the end of the 20th century and the beginning of the 21st century, ethnomusicology from abroad introduced into musicological circles in mainland China a trend towards writing “thick description” of music as culture. This was originally a good thing and improved musicological research. However, some musicology articles lacked internal connection between music analysis and thick description, and was criticized by some scholars as “liǎngzhāngpí 两张皮 (literally, “having two skins”).

[2.6] I found that the intervention of linguistics of music can contribute to solving the problem of having liǎngzhāngpí. This is because linguistics of music brings the sounds of chàngcí into the purview of music analysis. The unique characteristic of the chàngcí, being a simultaneous carrier of both musical and literary signs, allows music analysis (analysis of the sounds of chàngcí) and cultural “thick description” to combine naturally, as a matter of course.

[2.7] Therefore, I believe that the introduction of linguistics of music is an important way for musicology to conduct “thick description” of regional musics while overcoming the phenomenon of having “two skins.”

Ⅲ. Demand for Music Composition with Chinese Elements

[2.8] Let me first talk about original composition:

[2.9] In the contemporary era, music creators often pursued cultural characteristics by contemplating what “Chinese elements” mean. I really admire the pioneering spirit of these creative circles. They not only collected the tunes of traditional musics, but also went beyond the auditory realm to draw on images of mountains, rivers, lakes, seas and other geographic landscapes, thereby producing many multidimensional works of “Chinese elements.” Yet this kind of creative scale is often more suitable for large-form musical works. Given my perspective in linguistics of music, I pay more attention to creative groups who excavate “Chinese elements” by producing musical works with regional elements based on topolects. The strongest advantage of this type of work is the harmony they achieve between chàngqiāng and chàngcí. Guangdong Province is a prominent site of this kind of creative tradition, where Cantonese songs and Chao Yu songs (the languages in the Chaozhou and Shantou areas of Guangdong Province belong to the southern Min dialect) have existed for a long time. Musicians in Shanghai have also recently begun introducing songs in Shanghainese.

[2.10] I think one of the principal goals of the discipline of linguistics of music should be to lead more composers recognize, as musicians in Guangdong and Shanghai have already, that using topolects (or ethnic languages) in chàngcí 唱詞 is an essential element of regional musics and soundscapes, and is a true “Chinese musical element.”

[2.11] Let me now discuss acts of secondary creation:

[2.12] Linguistics of music has an important mission to provide music schools and vocal score markets with the aforementioned shuāngyīn Vocal Notation. Undoubtedly, only by using such scores can we successfully promote multi-regional and multi-ethnic vocal works with rich sounds among non-native singers.(10) Unfortunately, so far, shuāngyīn Vocal Notation arranged for multi-ethnic and multi-regional vocal musics is virtually absent in the Chinese vocal score market.

Concluding Remarks

[3.1] Dear Professor Yang Yinliu, please rest in peace. Although master’s and doctoral programs for linguistics of music have not yet been established, the team under its banner is growing year by year. Your notion of attaching importance to the relationship between language and music is being accepted by more and more people.

November 10, 2019

Postscript

[4.1] In 2020, for the first time in the country’s history, the center for post-doctoral studies of linguistics of music was set up at the Institute of Musicology at the Central Conservatory of Music. The center recruits post-doctoral graduate students at home and abroad, and has hired me as a co-advisor of the center. Since then, linguistics of music finally has its own research platform.

Appendix

The author’s related research results:

Qian Rong 錢茸

Department of Musicology

Central Conservatory of Music

No. 43, Baoja Street, Xi Cheng District

Beijing 100031

China

qrong@ccom.edu.cn

Works Cited

Merriam, Alan P. 1964. The Anthropology of Music. Northwestern University Press.

Qian, Rong 錢茸. 2018. Foundation of the Linguistics of Music语言音乐学基础. Central Conservatory of Music Press.

—————. 2020a. “Yuan zuo ‘Yuyan yinyuexue’ qizhi xia de yi ming zhanshi—xie zai Yang Yinliu xiansheng 120 nian danchen jinian zhi ji” 愿做“语言音乐学”旗帜下的一名战士—写在杨荫浏先生120年诞辰纪念之际” [Being a Soldier of the ‘Linguistics of Music’ Army— Written on the Occasion of the 120th Anniversary of Mr. Yang Yinliu’s Birth]. Yinyuewenhuayanjiu (Music Culture Studies) 3: 50–54.

—————. 2020b. Exploring Regional Charms Beyond the Musical Notes: Analysis of the Sounds of chàngcí 探寻音符之外的乡韵—唱词音声解析. China Youth Publishing House.

Yang, Yinliu 楊蔭瀏. 1983. “Initial Exploration into Linguistics of Music.” In Language and Music 语言与音乐, ed. Sūn Xuánlíng 孙玄龄, 1–93. People’s Music Publishing House.

Zhao, Yuanren 趙元任. 1937. “The National Tone in Sung Words (chàngcí)” 歌詞中的國音. Yinyueyuekan (Music Monthly) 1 (1): 47–55.

Footnotes

* I sincerely appreciate Jacob Reed’s review and encouragement, as well as valuable suggestions.

Return to text

1. Qian Rong 錢茸 (author and translator; Qian is the family name) is a Professor in the Department of Musicology at the Central Conservatory of Music, China. She is the first co-advisor of the country’s first center for post-doctoral studies of Linguistics of Music. The original Chinese version of this article was published as Qian 2020a, which captured the author’s 2019 speech at the 120th anniversary commemoration of Professor Yang Yinliu’s birth. The concepts discussed in the article can be found in Qian 2018 and Qian 2020b.

Return to text

2. Professor Yang Yinliu was an authority in the theory of traditional Chinese music and Chinese music history. He offered a course on “語言音樂學 (Linguistic Musicology)” at the Central Conservatory of Music in 1963, which mainly focused on phonological knowledge, the relationship between language and music, and Chinese pinyin as analytical tool. Due to the Cultural Revolution (1966–76) in China, his course was quickly terminated. In the 1980s, Sūn Xuánlíng 孫玄齡, a student of Professor Yang, organized the main contents of Yang’s 1963 lecture and included them in the collection Language and Music along with two other authors’ articles. The lecture was given the title “Initial Exploration into Linguistic Musicology,” published by the People’s Music Publishing House in 1983.

Return to text

4. In China, the earliest pioneer of linguistics of music was undoubtedly Professor Zhao Yuanren 趙元任, a master who straddled multiple fields such as mathematics, physics, psychology, linguistics, and music. He was the leader of linguistics and music for decades and began researching chàngcí in Zhao 1937. As this article derives from my speech at Professor Yang Yinliu’s commemorative event, it does not discuss any of Professor Zhao’s work. But I discuss Professor Zhao’s work in detail in Qian 2020b.

Return to text

5. Among all genres of vocal music, the element involving spoken sounds is known as chàngcí (literally, “sung words”). That is, what is in opera known as “libretto” and in songs known as “lyrics” are in a more general sense for all vocal genres collectively known as chàngcí. See Qian 2020b.

Return to text

6. Example from Qian (2020b, 205).

Return to text

7. The illustrations in the original Chinese manuscript have been replaced with new ones.

Return to text

8. See Chapters 8 and 9 of Qian 2020b.

Return to text

9. ‘Yùeshūo’ in Chinese Vocal Music 中国‘乐说’研究” is a special research project of “Unpopular and Esoteric Projects 冷門‘絕學’和國別史等研究專項” supported by the National Social Science Fund 国家社会科学基金 in 2019 (Project Approval Number: 19VJX004). Please refer to Chapter 5, Section 2 of Qian 2020b.

Return to text

10. The translation of this paragraph includes a few literal changes from the original published Chinese work (the author and translator of the work are the same person).

Return to text

Copyright Statement

Copyright © 2024 by the Society for Music Theory. All rights reserved.

[1] Copyrights for individual items published in Music Theory Online (MTO) are held by their authors. Items appearing in MTO may be saved and stored in electronic or paper form, and may be shared among individuals for purposes of scholarly research or discussion, but may not be republished in any form, electronic or print, without prior, written permission from the author(s), and advance notification of the editors of MTO.

[2] Any redistributed form of items published in MTO must include the following information in a form appropriate to the medium in which the items are to appear:

This item appeared in Music Theory Online in [VOLUME #, ISSUE #] on [DAY/MONTH/YEAR]. It was authored by [FULL NAME, EMAIL ADDRESS], with whose written permission it is reprinted here.

[3] Libraries may archive issues of MTO in electronic or paper form for public access so long as each issue is stored in its entirety, and no access fee is charged. Exceptions to these requirements must be approved in writing by the editors of MTO, who will act in accordance with the decisions of the Society for Music Theory.

This document and all portions thereof are protected by U.S. and international copyright laws. Material contained herein may be copied and/or distributed for research purposes only.

Prepared by Aidan Brych, Editorial Assistant

Number of visits:

4044