Gusti Putu Madé Geria’s Theory for Balinese Gamelan

Michael Tenzer

KEYWORDS: Gusti Putu Madé Geria, Balinese gamelan, Prakempa, Tantrism, Melodic pattern classification

ABSTRACT: The contents of a set of undated, handwritten notebooks by Balinese musician Gusti Putu Madé Geria (1906–83) are first assessed in historical perspective. He was in effect the first Balinese musicologist, but his work evokes older anonymous lontar (palm leaf manuscripts) of Balinese scribes, themselves heir to traditions of Hindu-Buddhist thought. Some of his descriptions of instruments and ensembles mimic the discourse of high priests and invoke unseen worlds. I will briefly consider their relationship to specific lontar and to Tantrism (Bandem 1986, Becker 1993). Geria’a analytical thinking dwells in a network of ideas bridging his precolonial umwelt with an inchoate Indonesian modernity. He invented a witty cornucopia of terms in Balinese for instrument functions and melodic patterns where none previously existed in oral tradition. His lexicon is a product of his insight into particular linear-intervallic structures and their motile impulses. Geria in effect provides a theory enabling close readings of “classical“ Balinese gamelan repertoires, which teem with these patterns. I introduce a selection of them, amplifying (and culturally decoding) Geria’s classifications and notations with a more granular but, I aver, ethnographically relevant approach. The last part of the paper sorts Geria’s terms by lexical field: the natural world, emotion or character, action and perception, and the unseen world. Finally I compare Geria’s lexicon with my own published work on the same musical material, assessing the epistemological gaps within each and between the two.

PEER REVIEWER: Ed Garcia

VIDEO CREDITS (left to right and front to back row in Part IV): Walker Williams, Putu Ichi Oka Swaryandana, Michael Tenzer, Oscar Smith, Iljung Kim, and John Lai. Videography, recording, and editing, March 2023: Jason Winikoff.

DOI: 10.30535/mto.30.4.16

Copyright © 2024 Society for Music Theory

Translator’s Introduction

[0.1] This essay and translation presents contributions to the theory of Balinese gamelan authored by Gusti Putu Madé Geria (Gree-ah; 1906–1983) of Buagan, South Bali. Geria had impact in several media: texts that named and classified gamelan instruments and performance practices, transcriptions of dozens of village repertoire items (and original compositions in their idiom) into Balinese notation, archival research, composition in contemporary genres, pedagogy, and performance. His writings had precedent in anonymous lontar (palm leaf manuscripts) of Balinese scribes, which in turn are heir to still older traditions of Hindu-Buddhist scholarship and aesthetics. Much of his painstaking work, preserved in undated personal notebooks using a combination of semantically rich Balinese and Old Javanese (Kawi) with a more neutral Indonesian, remains unpublished; some is available (see Bandem 2019). But when Geria began, state and state-run educational contexts for dissemination did not yet exist. He did the work to satisfy his desire to learn and preserve, and his distinction was to have focused on gamelan; however some of his contemporaries devoted their lives to promulgating other Balinese performing arts in their ways, so he was part of something broadly emergent.(1) His reputation grew throughout his lifetime and since his passing, beginning in traditional village oral networks and gathering prestige through the advent of a culture of publication. He is thus deservedly seen as a parent of modern Balinese musicology.

[0.2] As a young man living under Dutch rule and through Indonesia’s 1946 independence, Geria was among the last generation of musicians to serve at the Puri (palace) Pemecutan in the capital, Denpasar. Digging in the Puri’s archives he brought to light the (likely 18th–19th century) Prakempa, a lontar (palm-leaf manuscript) unique for its exclusive focus on gamelan. Prakempa (and the related Aji Gurnita lontar)(2) are gnomic and cosmological, and unlikely to have been intended for any public. At the Puri, Geria was immersed in gamelan as well as in the realms of Hindu-Balinese poetry and its vocal practices, which bore many named conventions of poetic meter and form. It is generally understood that gamelan music did not possess such a nomenclature then, or, at least, there is no record, oral or written, of one. Geria adapted words used to label formal components of poetry for instrumental music, and invented outright—employing a cunning diversity of metaphoric, symbolic, and evocatively descriptive labels—a cornucopia of terms for instrument functions and melodic patterns. Awakening to Bali’s presence among other cultures nationally and internationally, Geria’s work connects the anonymous musical thought of the past to an emergent Indonesian and international culture of explicit musicological attribution.

[0.3] From 1952 to 1955 Geria, along with Balinese colleagues Nyoman Kaler and Nyoman Rembang, taught in Surakarta (Solo), Java at the young Konservatori Karawitan, Indonesia’s first higher education school of music and dance. In Solo, local histories of court and Dutch colonial power were more deeply entwined than those in “outlying” Bali. Even before the school’s founding, these conditions inspired some Javanese musicians to model Western attitudes toward knowledge standardization. A formal academic culture of publication, though later increasingly emphasized by the Ministry of Education, was yet to emerge, however. Faculty trained in village or court tradition were hired to teach, and whether or not they would morph adventitiously into publishing academics through the change of context, as some eventually did, was not an explicit consideration. Pedagogy was practice, as it still is. Yet by then some distinctive Javanese intellectual musicians were impelled to write about gamelan, so that by the 1950s the urge to theorize was not unheard of. This inspired Geria as well as Rembang (who was younger and whose own later writings were inspired by Geria’s).(3)

[0.4] Returning to Bali, Geria led the RRI (Radio Republik Indonesia) full-time resident gamelan in Denpasar. Its members were senior musicians of remarkable expertise, and all looked up to him. He also taught at Bali’s own fledgling conservatories, wrote, and composed. In 1981–82 I attended many daily rehearsals at RRI, spoke often with Geria, and learned some of his music. I grasped that he was a polymath, and understood the solace that thinking about his music provided for him. When he died the following year he (and his family) had entrusted his notebooks to I Made Bandem. Bandem (b. 1945) is a performer and scholar who was the first Balinese to earn a PhD in Ethnomusicology (at Wesleyan in 1980), and has served in multiple international and local academic, cultural, and political leadership positions over an influential career. Bandem translated, commented, and expanded upon Geria’s work in several of his Indonesian publications (1986, 1992, 2013, 2019). I better understood Geria’s fuller significance after reading these.

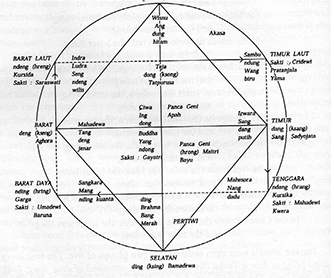

[0.5] To enable comparison with other music theories represented in this issue, Geria’s work needs to be culturally situated. Much of his rhetoric is of a piece with the Prakempa he brought to light. It is sometimes as if Geria ventriloquizes Prakempa’s putative author Siddartha Gautama (who, bearing the Buddha’s eponym, may have been a real person, a pseudonym, or an attribution for an assemblage of texts). Prakempa is an artifact of precolonial culture wherein a mix of languages (Balinese, Old Javanese, and Sanskrit) and intertextually-related expressive genres (music, dance, theater, visual arts) were widely but unequally pervasive in village, court, and priestly realms of society. Prakempa’s pivotal mandala-like illustration, the pangider bhuwana (dispersion around the cosmos; see Example 1) comprises heterarchical groupings of tones, letters, colors, gods, and parts of the body, each “installed” at one of ten cardinal direction points (North, Northeast, East, Southeast, South, Southwest, West, Northwest, and above and below the Center).(4) These associations invoke the expertise of high priests, with their esoteric knowledge of niskala (the unseen, the metaphysical). But while Prakempa is a product of court culture and written in Old Javanese, its aim was to emplace Balinese music genres of all kinds in a universal context, humming with vital energy.

Example 1. Pangider Bhuwana (adapted from Prakempa in Bandem 1986, 14)

(click to enlarge)

[0.6] Ambiguity and enigma are aspects of learning and knowledge in the intertwined Balinese and Javanese cultural spheres, even more so in the past as knowledge production was decentralized. Ambiguity has a positive valuation and reflects blends of indigenous beliefs with layers of accreted mysticism of Indic and Islamic origin, including Tantrism. Utama (2016) documents Tantrism’s embedded persistence in many of today’s Balinese material symbols, food, music, dance, and rituals, even if only priests or erudite persons could name these connections. Writers on Javanese music of Geria’s generation such as Sastrapusaka ([1953] 1984) evoke it, and Judith Becker explored the topic in depth (1993). Tantrism’s “subtle body,” like the pangider bhuwana, is a microcosm of the universe hosting energy points (chakras) and channels for energy flow via breath or fluid. When Geria associates sounds and instruments to parts of the body and bodily action, or to gods or to natural phenomena, he joins with Sastrapusaka and others. As Becker aptly wrote, “it takes a certain suspension of disbelief on the part of the reader to begin to approach Sastrapusaka’s story with sympathetic understanding” (59), as it does for reading Geria. But Geria gradually passes from Prakempa’s metaphysical style to a discourse on the play of tones and the concrete sensations they produce. Having sculpted these worlds as continuous, even a non-Balinese reader can connect the umwelt of precolonial Bali to an international emergent music theory based on earthly perception and cognition.

[0.7] Below in Part I Geria sets forth the significance of certain instruments, their construction, their sound, and the tones they produce. Parts II, III, and IV comprise lists of terms—some borrowed from Prakempa, others coined by him—describing performance practice. In Part II general qualities of instruments and their playing techniques are characterized. In both Parts I and II the rhetoric mirrors Prakempa. By Part III and IV we come to specific patterns and techniques, having entered a realm of insights based on particular linear-intervallic patterns and the motile impulses they evoke. Here we are closest to the notes themselves, hence what many would aver to be music analysis.(5) I amplify Geria’s words with material from Bandem’s publications, merging this with bits taken from our 2022 discussions. Drawing also on my own experience with gamelan, I venture an English parsing of the referentiality Geria’s delightful lexicon has for Balinese musicians. Fundamentals of gamelan instrumentation and playing technique are explained as needed.(6) Urged on by Bandem, I conclude with some comparative perspectives. In parts I–III Geria’s own writing is given in the left column and translated at right, with Balinese or classical Javanese terms retained. Further explanatory notes, fully in my own voice, are given in single-column format.

I. Niyan Pitegesing Rebab lan Suling (The Significance of Rebab and Suling)

[1.1] The bowed spike lute rebab and the bamboo end-blown flutes suling play the melody in the Gamelan Gambuh, an ensemble dating perhaps to as early as the fifteenth century, and commonly understood to be the crucial precursor of later gamelan composed of bronze keyed instruments and gongs. Gambuh, already rarely seen in Geria’s time, was nonetheless cultivated in the village of Pedungan, near to Geria’s home village Buagan, and at the Puri Pemecutan, where Geria trained, also very close by. These contexts were formative and may explain why his text begins as it does. N.B.: Sang Hyang, used often below, is an honorific for deities.

I.1 Ikang rebab kawangun dening taru, dening babasar, dening pasu, dening kawat, dening rambut; hana suku, hana sarira, hana wijang, hana wungkur, hana angga, hana tangan roro, mwang hana murda. Niyan piteges babasar, babasar, ngaran kau, kau ngaran, kaweruhan, wruha nyipta krana, wruha ngidep, angidep rasa lwiring budhi. |

I.1 The rebab is made of wood, from coconut shells, parchment from stomach lining, from wire, from [horse] hair; it has feet, there is a body, there is skin, there is a back, there is a torso, there are two hands, and there is a head. Babasar is a vessel (kau), kau means knowing, knowing about creating, knowing about thoughts, knowing about affect, and knowing human nature. |

I.2 Hana saking pasu, pitegesing pasu, ngaran babad; pitegesing babad, ngaran wiwit, wiwiting sabda bayu. Ika marmanya hana sabda idep; apan kawruhaning idep, idep anyipta, idep angawe sabda. Sabda angawe bayu, hana idep, sabda, bayu, mangkana pitegesing babad. |

I.2 Thus there is pasu [materials made from domesticated animals], pasu connotes the beginning, the origin of sound and energy. This is why there is sound and thought; because it can know the mind, the mind creates, the mind makes sound. Sound makes energy, there is thought, sound, energy, this is the significance of the origin in pasu. |

I.3 Hana sarira, apan sarira angingkup salwring swara, laras patutan, lwirnya, swara patut pitu. |

I.3 There is an essence encompassing all tones, tuning and modes, a 7-tone sound. |

I.4 Swara patut salendro, swara patut pelog, ika swara kaingkup dening sarira, marmanya ingaranan angkus prana. |

I.4 The sound of the slendro scale, the sound of the pelog scale, they are the essence of sound, which is called angkus prana. |

I.5 Piteges adegan saking kayu, kayu ngaran kayun, kayun sujati angulati kawruhan adegan, ngaran pandiriyan. |

I.5 The significance of pieces of wood [the wood used to make the rebab]: wood connotes desire, desire to deeply understand the trunk (body) that enabled the making of the instrument. |

I.6 Piteges kawat, kawat ngaran iti swara kang lwih kukuh, apan kawat ingaranan otot, apan otot maka jalaraning swara, apa marmanyan roro angangge kawat, apa wetuning swara saking roro, swara wetu saking rengira sanghyang smara mwang sanghyang ratih, smara ngaran laki, ratih ngaran wadu, swaraning smara ngaran kama nada, swaraning ratih ngaran kama sraga. Rikalanya anunggal swara ika, hana swara karenga ngararengih ngalup manis, kadi reng pangucapira sanghyang smara ratih, patemuan nira murda, ring murda panunggara nira sanghyang ardanareswari, apan sira wenang surup sinurup, ganti gumanti, matemahan ring windu nada candra. |

I.6 The significance of wire [for the two rebab strings]: wire gives a good and strong sound, because wire is muscular, the muscle brings forth sound. Why use two wires? The sound that comes from two sources, one from the Sang Hyang Semara and the other from Sang Hyang Ratih [manifestations of a love deity]. “Semara” indicates male, “Ratih” indicates female, the voice of Semara is called kama nada, [kama = desire; nada = tone] the voice of Ratih is called kama sraga [sraga = form]. When these voices become one, there is a tinkling, sweet sound, like the vibrations of Sang Hyang Semara and Ratih’s words at their summit, at the highest realm of Sang Hyang Ardanareswari [a manifestation of Siva and his consort Parvati unifying male and female] because he can go in and out, again and again, on the tones of Windu Chandra [windu is a point, an essence; chandra can suggest brightness or the moon]. |

I.7 Hana mwah swara wetu saking pring, ngaran suling, suling ngaran bumi laras, apan salwring laras patutan juga mungguh ring suling, suling paraganing laki, rebab paraganing wadu, apan swaraning suling reng pangucapira sang hyang smara, swaraning rebab pangucapira sang hyang ratih, hana swara manis ngarerengih, mwah swarangalup manis, apan matunggalan pangucapira sang hyang smara ratih. Mangkana kalingganya. |

I.7 There is another sound that emerges from bamboo, namely the suling [bamboo flute]. Suling signifies the earth as if tuned, because all the tunings and modes are contained in the flute. The flute is the embodiment of maleness, and the rebab of the female, because the sound of the flute is the source of the sound from Sang Hyang Semara, the sound of the rebab comes from Sang Hyang Ratih. A very melodious, sweet high voice comes from the singular voice of Sang Hyang Semara and Ratih combined. |

[1.2] Now Geria changes tack, introducing other ensembles and instruments, and dealing with their individual tones and intervals between them, musical functions, and in some cases their cosmological origins and source of energy in the human body. He begins with gamelan gender wayang, the quartet of ten-keyed metallophones that accompany Balinese shadow plays and other rituals. Then he briefly covers instruments of a large bronze gamelan, presumably a gamelan gong kebyar: kajar, a small mounted gong; the family of metallophones (from low to high register) possessing a single-octave-range jegogan, jublag, and panyacah; those with a two-octave-range giying, gangsa pemadé (not explicitly mentioned) and gangsa kantil(an); and last but not least, the hanging gongs, the kendang (drums) and cengeceng (cymbals).

I.8 Niyan gagebug gender wawayangan, kumbang atarung ngaran, yaning gebug siki-sikinya, yaning gebug sanunggal, eka sruti ngaran, yaning gebug tan paselat, anunggal pati ngaran, yaning gebug selat siki, candrapraba ngaran, yaning gebug selat kalih padu arsa ngaran, yaning gebug selat tiga, dahana muka ngaran, yaning gebug selat pat anerang sasi ngaran, yaning gebug selat panca, anerang wisaya ngaran, yaning gebug selat nem, gana wadana ngaran, yaning gebug selat pitu, angelangkah giri ngaran, yaning gebug selat kutus asti aturu ngaran. Mangkana kalinganing gagebug gender pawayangan. |

I.8 As for the technique of playing gender wayang, it is called kumbang atarung [quarreling bees] if all the keys are struck one by one. If only one is struck, eka sruti [one sound] is the name. If two adjacent keys are struck it is called pati [dead stroke]. If two keys separated by one in-between are struck it is called candra praba [moonlight]; if two in-between the name is padu arsa [united desire]; if three are in-between the name is dahana muka [face aflame]); if four it is called anerang sasi, [the clarity of moonlight]; if five, it is called anerang wisaya [the clarity of sense perception], if six, it is gana wedana [face of the wise elephant god Ganesha], if seven it is called angelangkah gunung [mountain-sized stride], and if eight, asti aturu [sleeping elephant]. These are the types of intervals on gender wayang instruments. |

I.9 Niyan gagebug kajar, kajar ngaran amangku irama, eka laksana ngaran, mwang prana canda ngaran, yaning jegogan pamangku swara ngaran, guru. Yaning gagebug giying ngaran panuntun, ngaran lagu. Yaning gagebug jublag kreti suci ngaran dirga. Yaning gagebug panyacah panasta slampah. Yaning gagebug sarwa gangsa, kantil rswa ngaran. |

I.9 As for kajar [a small gong held in the lap or placed on a stand that sounds the main beat; the root word ajar means both learn and teach], it oversees the rhythm, alone among the instruments; it is the breath and guide of music (prana canda). Whereas the jegogan manages the [core, scaffolding] melody, that is to say is its guru. What the giying plays is called the guide panuntun, it provides the most songlike version of the melody [that is, in the manner of sung poetry]. The melodic movement of the jublag is sacred and enduring (kerta suci atau dirga—holy court of justice or long/prosperous). A panyacah stroke is panasta slampah. The gangsa parts, including the kantil, are called reswa. |

I.10 Iki wekasing swara, lwirnya yan swaran gong, wetu saking ageni yan ring anggasarira, adalan ring sorning lidah, agora ngaran, yan swaraning kendang, wetu saking mega mendung, biyomantaragora ngaran, udantya ngaran, adalan ring luhuring lidah yan ring anggasarira, yan swaran cengceng , wetu saking banyu arnawasruti ngaran, anudantya ngaran yan ring anggsarira, adalan ring untengan asilat. |

I.10 The final sound, the sound of gong, emerges from the fire in our body, it is under the tongue, the name is agora. The sound of drums is borne from the great sky above, biyomantaragora, it is called udantya and located above the tongue, anggasarira. The cengceng sound is borne from the water arnawa sruti, in the body its name is anudantya, centered on the subtle energy in the tongue. |

II. Nama-nama Pukulan Instrumen (Names for Instrument Playing Techniques)

[2.1] Here Geria names musical instruments trompong (row of tuned gongs played by a single musician), reyong (row of tuned gongs usually played by four musicians), gendér (metallophone played with a round-headed mallet in each hand), gambang (an instrument, also common in Java, with wooden slats for keys), gerantang (an instrument made from a row of tuned bamboo tubes suspended in a frame), genggong (a jew’s harp) plus rebab, suling and kendang (identified earlier). He mentions gamelan genres which I briefly describe below, retaining the Balinese terms he coined and defining them with some suggestion as to the resonances they would have for Balinese. NB. Other than the terms themselves, which remain in Balinese, Geria switches to Indonesian here and henceforth.

II.1. Nama pukulan instrumen seluruhnya. Misalnya pukulan trompong pangede. Pukulan trompong 8 jenis banyaknya, yaitu: 1. wiwitan, 2. ngembat, 3. nyiliasih, (see also Sastrapusaka 21) 4. nguluin (nabhe), 5. nerumpuk, 6. ngantu, 7. niltil, 8. ngunda. Nama kesatuannya disebut babancangan. |

II.1. Techniques for playing instruments. For example there are eight ways to play the trompong pangedé. [Geria supplies the 8 names here but then only defines them in Part III below so I omit them here]. As a group they are called babancangan [a bunch (of grapes)]. |

II.2 Pukulan trompong semar pagulingan, iber-iberan namanya. Banyak jenisnya sama dengan nomor 1 (satu) di atas. |

II.2. The technique of playing trompong in gamelan semar pegulingan [a court ensemble playing a delicate and refined repertoire] is called iber-iberan. The names of the ways to play it are the same as those for number 1 above. |

[2.2] Iber-iberan is a small bird such as a chicken or dove released to fly free during a cremation ritual, thus paralleling the human soul’s departure. The idea of lightness and freedom evoke the buoyancy and animation of semar pegulingan music.

II.3 Pukulan rareyongan, iwak magajah mina namanya. |

II.3. Reyong technique is called gajah mina [a legendary fish]. |

[2.3] Gajah mina is a legendary fish with an elephant’s head, a traditional image of which festoons cremation towers for people in certain Balinese lineages. The reyong’s main musical function is to embellish melody, and the character of gajah mina is understood as wanting to follow, accompany, escort—and in this case via cremation—to the next world.

II.4 Pukulan trompong semar pagulingan seperti di atas. |

II.4 Ways of playing the trompong semar pegulingan are the same as those given above [i.e., in II.1.] |

[2.4] There, Geria implicitly refers to the trompong used in gamelan gong gedé, which is larger than the one used in gamelan semar pegulingan, referenced here.

II.5 Pukulan gendér palegongan atau giying, tadah rawit namanya. |

II.5. The technique of playing gendér [equated here with giying; see also above] in the gamelan pelegongan. |

[2.5] Gamelan pelegongan is an ensemble similar to semar pegulingan that accompanies the iconic legong dance genre] is called tadah rawit [this means “of small and beautiful character,” a resonance much like the characterization of semar pegulingan in II.2 above.

II.6 Pukulan gendér babarongan, untal antil namanya. |

II.6. The technique of playing gendér in the gamelan bebarongan [much like the pelegongan, and used to accompany the dance of the lion-dragon barong] is called untal-antil [to wave back-and-forth like the barong’s tail]. | |

II.7 Pukulan gendér pawayangan, kupu-kupu atarung namanya. |

II. 7. The technique of playing gendér in the gamelan gender wayang is called kumbang atarung. |

II.8 Pukulan gendér angklung, capung manjus namanya. |

II.8 The technique of playing gendér in the gamelan angklung is called capung manjus. |

[2.7] The ubiquitous angklung gamelan has a four-tone scale and instruments with but four keys—a single octave. Though its music can be complex the instrument is quick to navigate. Capung manjus means bathing dragonfly; an idiom describing a “water-skimming” quick bath for a person as well.

II.9 Pukulan reyong angklung, kaget asih namanya. |

II.9 The technique of playing reyong in the gamelan angklung is called kaget asih. |

[2.8] This means sudden love or crush and evokes the same deft quickness as II.8. The four tones of each octave of the angklung’s reyong are played by pairs of musicians—perhaps a matchmaking opportunity.

II.10 Tandang rarebaban, buta anggawasari namanya. Semara nada nama suaranya. |

II.10 Rebab playing style is called buta anggawasari; its sound is semara nada. |

II.11 Tandang sasulingan, tunjung arip, merdukomala nama swaranya. |

II.11 Suling playing style is called tunjung arip, its sound is called merdukomala. |

[2.10] Tunjung is lotus and arip is sleepy; suggesting that the flute finger holes opening and closing are like the lotus. Merdukomala is the name of an Old Javanese poetic meter; its constituent words merdu and komala both index sweetness, softness.

II.12 Pukulan kendang atau tandang kakendangan, geleng pangasuh, meganada nama suaranya. |

II.12 Drum technique or style is called geleng pangasuh, its sound is meganada. |

[2.11] Geleng is a word for head that also suggests focus and concentration; and asuh is diligent. The term suggests the watchful leadership role of the drum in the ensemble. Meganada literally means big sound, but it is also the name of the demon-king Rahwana’s powerful son (of the Ramayana epic).

II.13 Tandang gagebug gambang, kesa mura. Banyu maga nama suaranya. |

II.13 Gambang style is called kesa mura; its sound is banyu maga. |

[2.12] As well as being an instrument, in Bali gambang also names an ensemble usually comprising four gambang and two bronze metallophones. Kesa mura means irregular and free, which likely connotes the fact that gamelan gambang music is not regulated by gongs and conventional gong structures. Banyu marga means flowing water, suggesting the continuous rippling texture of gamelan gambang music.

II.14 Tandang gagebug gerantang joged bumbung, bramara ngisep sari. Pangirik nama suaranya. |

II.14 Gerantang joged bumbung style is called bramana ngisep sari; its sound is pangirik. |

[2.13] Gerantang joged bumbung refers to an ensemble of gerantang accompanying ngibing, a flirtation dance. Bramana ngisep sari means “beetle sips flower essence”; pangirik is a tickling sensation. The juxtaposed and somewhat incongruous imagery of beetle, flower, and tickling cunningly reveals the potential of ngibing, which in yesteryear led to more than flirtation.

II.15 Tandang anyetat genggong disebut amebet lati, samas nyata nama suaranya. |

II.15 The technique of plucking the genggong is called amebet lati; its sound is samas nyata. |

[2.14] The genggong is a jew’s harp made with a wooden tongue set in a small frame held in the mouth. One vibrates the tongue by jerking a stick tied to a cord attached to the tongue; the sound is resonated by the oral cavity. Amebet means tide or wave, and lati is lips, thus, a wave of sound coming from the lips. Samas means four hundred and nyata means to drain or to dry—is Geria saying that after so many yanks one’s mouth is dry? None of my Balinese interlocutors know.

III. Arti dalam Pukulan, Misalnya dalam pukulan Trompong (Kinds of playing techniques, for example on the trompong)

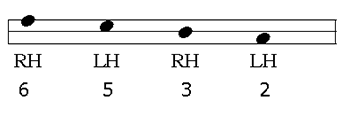

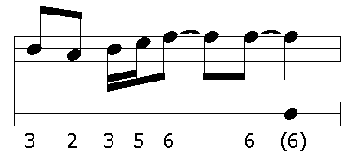

[3.1] Geria’s focus in Parts III and IV is on two kinds of melodic embellishment: non-interlocking and interlocking. The non-interlocking embellishment shown in Part III is for a single player and allows improvisatory freedom in both rhythm and pitch so long as one arrives at periodic goal tones (also played on the single-octave jegogan instruments); the examples shown are thus models, one of many possible realizations. Geria’s examples all apply to the trompong, an instrument forefronted in prestigious court gamelan—the palegongan, semar pagulingan, and the gong gdé. I show both the kepatihan (cipher notation) provided and my own modified 3-line staff for the trompong and, when needed, a single-line staff for jegogan. Geria notated his examples on particular pitches in a five-tone pélog, conventionally numbered 1,2,3,5, and 6. But they could be played at any transposition. To convey this my additional three-line staff shows pitch contour only, and only when there is a specific pitch goal. The instrument is played with a long string-wound mallet in each hand and Geria’s terms sometimes apply to the ‘sticking’, that is which hand plays which tone. Some notations thus indicate LH and RH.

[3.2] Balinese scale tone solmization is ding (1), dong (2), deng (3), dung (5), and dang (6). Tones 4 (deung) and 7 (daing) are only invoked for pélog’s seven-tone parent scale. The latter only appears in III.1, At the time Geria was writing the five-tone pélog was nearly ubiquitous in Bali and gamelan using the seven-tone one were heard much less frequently. These examples are paired with videos III.1–8.

III.1 Pukulan ngembat, artinya ngoktap (pukulan satu oktaf). Ngoktap artinya, dalam suatu tempat dari tepi ke tepi. Itu arti ngembat. Pukulan satu oktaf adalah pukulan yang berselang empat nada dalam gamelan palegongan yang menggunakan laras pelog lima nada, seperti yaitu 235612 (dong, deng, dung, dang, ding, dong). Sedangkan dalam gamelan semar pagulingan yang menggunakan laras tujuh nada akan terlihat seperti berikut: 23456712 (dong, deng, deung, dung, dang, daing, dong). Artinya pukulan berselang enam. |

III.I Ngembat means octave (ngoktap(7)), from end to end. Playing an octave means an interval of four tones [not counting the octave tones] in the palegongan, which uses five-tone pélog tuning, that is, tones 235612 (dong, deng, dung, dang, ding, dong). Whereas in gamelan semar pagulingan using the seven-tone scale it will be 23456712 (dong, deng, deung, dung, dang, daing, dong), an interval of six tones. |

Example III.1. Ngembat (click to enlarge) | Video III.1. Ngembat (click to watch video) |

III.2 Pukulan nyiliasih artinya pukulan kembali dari tepi mengarah ke tengah sama bekerja. Pukulan ini adalah pukulan silih berganti dari tepi ke tengah. |

III.2. Nyiliasih is a motion from one end of the instrument toward its middle with [the two hands] playing in alternation. |

[3.3]Nyiliasih means to love one another, here in reference to the graceful motion of the two hands crossing over one another.

Example III.2. Nyiliasih (click to enlarge) | Video III.2. Nyiliasih (click to watch video) |

III.3 Pukulan angurit yaitu artinya membuat garis-garis. |

III.3. Angurit means to make lines. |

[3.4] “Lines” refers to the grace notes and special technique for playing two adjacent notes with the same hand, glancing off one gong’s boss and using the momentum to propel it to the next one.

Example III.3. Angurit (click to enlarge) | Video III.3. Angurit (click to watch video) |

III.4 Pukulan nalutur artinya, penatas irama atau penatas lampah, reswa namanya. Pukulan ini sama artinya dengan pukulan nugtug. |

III.4 Nalutur is mastery of rhythm, the showing of light, or reswa; it is also attainment, or reaching a goal. It is also called nugtug. |

[3.5] The initial note of each pair is in a subordinate metric position and the final stroke coincides with a significant goal tone played on the mid and low-range metallophones and often other instruments too.

Example III.4. Nalutur (click to enlarge) | Video III.4. Nalutur (click to watch video) |

III.5 Pukulan nerumpuk artinya membuat penimbunan atau pengumpulan barang sesuatu yang dicintai. Merupakan pukulan di atas sebuah nada yang diulang berkali-kali biasanya dengan ritme yang bergerak makin lama makin cepat atau sebaliknya. |

III.5. Nerumpuk means to hoard or bundle together beloved possessions. A tone is repeated several times in a rhythm that gets slower or faster bit by bit. |

[3.6] This is often heard in unmeasured passages called gineman trompong.

Example III.5. Ngerumpuk (getting faster, and getting slower) (click to enlarge) | Video III.5. Ngerumpuk (getting faster, and getting slower) (click to watch video) |

III.6 Pukulan nguluin artinya pemberian tanda kepada anak buahnya, pawisik (nabhe) namanya atau pangajen (guru). Pukulan mendahului memberikan tanda bahwa melodi akan berjalan ke arah tertentu. |

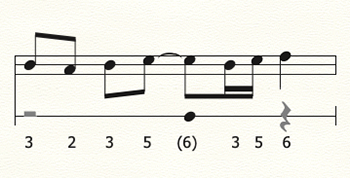

III.6 Nguluin is an indication to one’s followers that one is leading (or teaching to go) somewhere. Striking the tone in advance signals that the melody will progress in a certain direction. |

[3.7] Since the trompong plays a lead role, what is meant by “followers” is the rest of the musicians in the gamelan; in Example III.6 the direction is the goal tone (6) and the trompong’s prior arrival on 6 is an anticipation.

Example III.6. Nguluin (click to enlarge) | Video III.6. Nguluin (click to watch video) |

III.7 Pukulan ngantu, artinya ngungkurin, lambat datang, pangemban namanya. Oleh karena dia berfungsi sebagai pengembala anak buahnya (pangkuan atau pangasuh). Pukulan yang jatuh satu ketukan setelah paniti calung atau jublag, memberi kesan lambat dan menunjukkan kematangan seorang pemain trompong. |

III.7 Ngantu means hanging, waiting. The leader arrives late because it is the caretaker of its followers. Coming afterwards suggests the trompong player’s maturity and responsibility, as when the trompong attains the goal tone [6 in the example] a full beat after the other instruments do. |

Example III.7. Ngantu (click to enlarge) | Video III.7. Ngantu (click to watch video) |

III.8 Pukulan ngunda artinya, pengumpulan barang sesuatu di dalam pekerjaannya. |

III.8 Ngunda is to distribute something accumulated through work to others. |

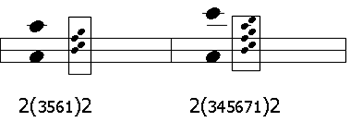

[3.8] As the tones within the repeat signs repeat, the player may at will substitute those on the right from time to time.

Example III.8. Ngunda (click to enlarge) | Video III.8. Ngunda (click to watch video) |

III. 9. Pukulan angindra artinya pencarian atau pangalihan gending-gending (wiwitan) namanya. Pukulan sendiri dan agak bervariasi yang memberi tanda pembukaan lagu. Makanya banyak pukulan trompong. Seperti: 1. wiwitan, 2. nabhe (nguluin), 3. ngembat, 4. nyiliasih, 5. ngoret, 6. ngantu, 7. ngunda, 8. nerumpuk. |

III.9 Playing andira means to look for or seek the beginning (wiwitan) of a composition. There are many ways for the trompong, playing alone, to do this. For example: 1. wiwitan, 2. nabhe (nguluin), 3. ngembat, 4. nyiliasih, 5. ngoret, 6. ngantu, 7. ngunda, 8. nerumpuk. |

[3.9] Geria here iterates many of the above terms, indicating that these embellishments can be used as intros. (There is no corresponding video.)

IV. Soal Ubit-Ubitan Sekati (Refined interlocking (ubit-ubitan) techniques)

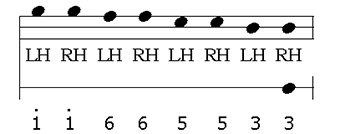

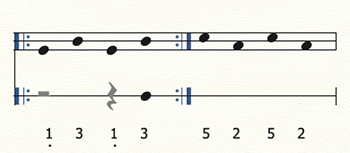

[4.1] Balinese interlocking patterns are played by pairs of musicians and on some instruments may involve improvisation, though in a different way than the patterns in Part III (see Tilley 2019). But Geria only addresses a type called ubit-ubitan, played on the upper-register gangsa (metallophone family). Most gamelan have eight gangsa. In ubit-ubitan rhythm and contour are fully specified, though patterns may perch on any set of scale degrees depending on the surrounding musical context. With one exception (IV.6) these patterns are very common and I speculate (since Geria’s list is not comprehensive) that they were chosen for that reason. Unlike the examples in Part III, for which a goal tone is shown only when a specific one is presupposed, these patterns are all aligned to melodic contours in slower-moving instruments. In a typical musical situation, the patterns would repeat one or more times before the music leads elsewhere.

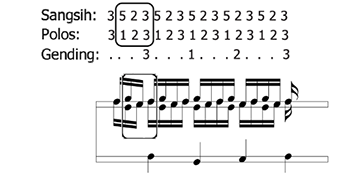

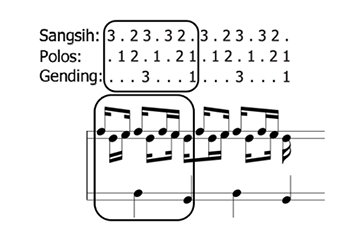

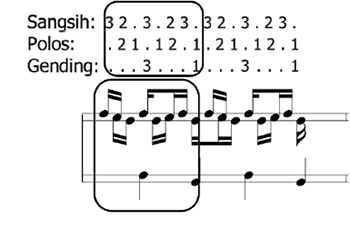

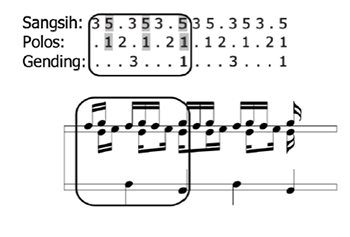

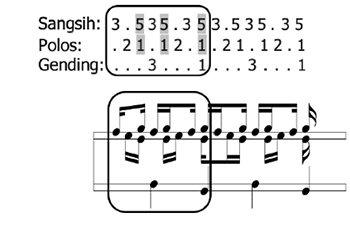

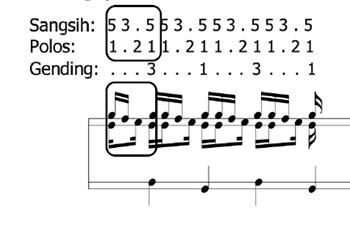

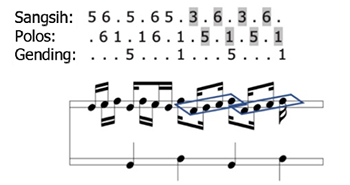

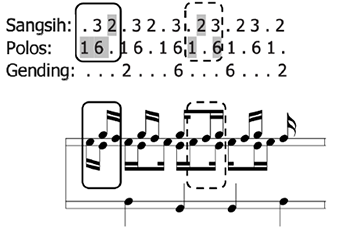

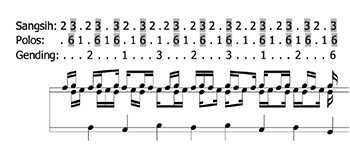

[4.2] Geria’s cipher notation is given, as well as modified staff notation using two two-line staves with the ubit-ubitan above and the slower moving gending line below.(8) On the ubit-ubitan staff the stems-down part is known as polos (basic). The stems-up part is the sangsih (different or complementary). As most Balinese music has an end-accented character, the staff notation places the beginning of a four-note group apart and unbeamed at the end of each pattern. The three tones that complete it on repeat are shown at the beginning. Boxes identify a repeating segment.

[4.3] Geria provided only the classification and gave no explanation for why he chose the names he did, but they conceal rich semantic and associative thought. My interpretations below were discussed with and endorsed by Made Bandem (conversations December 2022). Also with Bandem’s assent I reorder the presentation of the patterns from short to long and simple to complex. Geria gave no rationale for his original order, which, per Bandem 1992, was IV.11, 1, 4, 5, 7, 9, 10, 13, 14, 2, 3, 8, 12, 6.(9) These examples are paired with videos IV.1-14.

Di bawah ini adalah semua ubit-ubitan palegongan yang berpokok misalnya di dalam gagaboran atau di dalam lalonggoran dan kale, atau pangecet. |

Below are palegongan-style ubit-ubitan for gagaboran, lalonggoran, kale, and pangecet contexts. |

[4.4] Gagaboran, lalonggoran, kale, and pangecet are the names for different kinds of gong-cycle forms in dance pieces of the gamelan palegongan repertoire.

Example IV.1. Aling-aling (click to enlarge) | Video IV.1. Aling-aling (click to watch video) |

[4.5] An aling-aling is a wall at the gateway to almost all Balinese homes that forces someone coming in to turn immediately left or right. Its purpose is to prevent buta kala (malevolent powers believed to travel only in straight lines) from entering. This is one of two of Geria’s ubit-ubitan that does not feature interlocking rhythms. The three-note motive 123 in the polos (523 in the sangsih) repeats throughout, constantly backing up and trying again like a buta kala ramming into an aling-aling. At the end, at last, the 3 of the sangsih and polos aligns with the gending.

Example IV.2. Gagelut (click to enlarge) | Video IV.2. Gagelut (click to watch video) |

Example IV.3. Gagulet (click to enlarge) | Video IV.3. Gagulet (click to watch video) |

Example IV.4. Kabelit (click to enlarge) | Video IV.4. Kabelit (click to watch video) |

Example IV.5. Kabelet (click to enlarge) | Video IV.5. Kabelet (click to watch video) |

[4.6] IV.2 through IV.5 can be discussed together since they are similar and all paired with the same oscillating two-note gending pattern. Gagelut and gagulet are assonant synonyms meaning hug, embrace, or even wrestle. The patterns are of a subtype called ubitan telu (telu = three) in which the two parts use a total of three tones, sharing an inner tone; hence embracing. These are indeed ubiquitous in the repertoire. Kabelit and kabelet, similarly related as words, mean stuck, stubborn, unmoving. They are of subtype called ubitan empat (empat = four) in which the two parts use two different but scale-adjacent tones each. When sounded the lower tone of the polos and the upper tone of the sangsih coincide, creating a dyad that protrudes from the texture to create a syncopated 3+2+3 cross-rhythm (the greyed notes). While the inner tones jostle, this prominent interval is “stuck” in its place.

Example IV.6. Gagejer (click to enlarge) | Video IV.6. Gagejer (click to watch video) |

[4.7] Gagejer (from gejer, to shake) is an anomaly in that (according to several people I asked) it does not appear anywhere in the repertoire, though perhaps it did in Geria’s lifetime or his own compositions. Like IV.1 the parts do not interlock.

Example IV.7. Kabelet Ngecog (click to enlarge) | Video IV.7. Kabelet Ngecog (click to watch video) |

[4.8] This pattern is kabelet (stuck) at first, and then it ngecog (jumps). The jumping is the iterated leap over a scale tone: 3 to 6 (skipping 5) in the sangsih and 5 to 1 (next octave, skipping 6) in the polos, though their composite creates a stepwise line as the slanted rectangles show. This pattern is thus longer than previous ones and contains no internal repetition of its initial motive as all previous ones do.

[4.9] Tulak is to refuse, and wali to return or go back. The opening 3-note pattern with a down-then-leap-up contour (162) repeats, but once the polos 6 in the middle is reached, matching the gending, the contour pattern inverts to up-then-leap-down (126; dotted box) and returns to its point of origin.

Example IV.8. Tulak Wali (click to enlarge) | Video IV.8. Tulak Wali (click to watch video) |

[4.10] Oles-olesan is swiping or wiping, an apt description of the repeating pattern 32.23. in the polos. The mallet’s path on the keys needs a lateral wrist motion leftward for 32 and rightward for 23— just as one would move the hand back and forth with a cloth or paint brush, or glide a finger across a phone screen.

Example IV.9. Oles-olesan (click to enlarge) | Video IV.9. Oles-olesan (click to watch video) |

Example IV.10. Ubitan Nyendok (click to enlarge) | Video IV.10. Ubitan Nyendok (click to watch video) |

[4.11] Nyendok, to scoop (from sendok, spoon), evokes the opening 23 in the sangsih, which enters below the polos, scooping the composite pattern 235 upwards. N.B.: That feature notwithstanding, this ubitan telu pattern is much like gagelut and gagulet (IV.2 and 3) but Geria sets it in a gending twice as long (as the lower boxes show).

Example IV.11. Babaru (click to enlarge) | Video IV.11. Babaru (click to watch video) |

[4.12] Geria likely meant babaru to mean a whiplike inner force or strength. This is doubly apt.(10) Here the boxed motive recurs transposed up a step, then inverts (dotted box) to return to the starting point. In one sense the pattern conveys a directed kinetic motion Balinese call majalan, and always fits with gending, whose goal tones change for every iteration of the pattern (moving 5-6-5 3 in the example). It conveys energetic motion and is often played at fast tempi. In a more concretely physical sense playing the polos or sangsih requires a whipping or flicking motion with the wrist of the mallet hand. The polos’s 5.35.35 slashes to the right (35); ditto for the sangsih’s 3.23.23.

Example IV.12. Aling-aling Cunguh Temisi (click to enlarge) | Video IV.12. Aling-aling Cunguh Temisi (click to watch video) |

[4.13] In this playful term, aling-aling is the entrance wall described for IV.1 and cunguh temisi is a snail’s nose. The repeating 231 is much like IV.1 itself, but once the pattern breaks (in grey) the process begins anew. Perhaps it is like a snail persistently approaching the wall, and indeed the process is snail-paced in the sense that the larger repeating unit (boxed) is longer than others described thus far except IV.9. When I asked Bandem (conversations, December 2022) for other possibilities, he said “have you ever had a good look at a snail’s nose? It’s very convoluted!” N.B.: snails have four noses, or proboscises, but Geria was likely thinking of the many folds and ridges on the face of Lissachatina fulica.

Example IV.13. Nyalimput (click to enlarge) | Video IV.13. Nyalimput (click to watch video) |

[4.14] Nyalimput—to stumble or trip—with its eight-beat gending, is, along with its relative Nyalimped (Example IV.14) the longest pattern in Geria’s ubit-ubitan collection, and it has a distinctive profile. The jutting dyad 63, shown in grey, occurs eleven times. It recurs at an interval of three subdivisions except thrice—and this is where the tripping happens. At the two solid-boxed moments the distance is two, and in the dotted box it is four. Elsewhere 63s are equally spaced at a nice 3-against-4 cross-rhythmic gait, only to stumble again the next time around.

Example IV.14. Nyalimped (click to enlarge) | Video IV.14. Nyalimped (click to watch video) |

[4.15] Nyalimped means twisted, deformed. The gending is the same as in Nyalimput (Example IV.13), the polos and sangsih are perched on the same tones, and the 63 dyad occurs eleven times here as well, but in a more irregular configuration. Counting from the left it recurs at constantly changing gaps of 3, 2, 3, 4, 3, 3, 4, 3, 2, 3, and (wrapping to the beginning) 2 subdivisions. None of the foregoing examples are remotely as unpredictable as this.

Conclusion: Resonance of Geria’s Concepts in Bali and Abroad

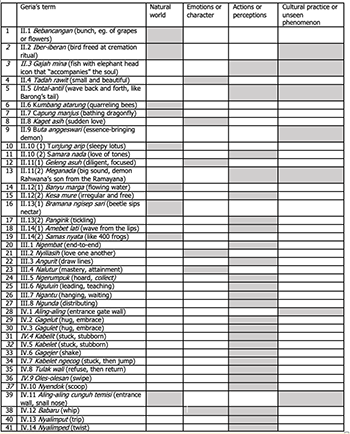

Example 2. Kinds of lexical fields for Geria’s terms

(click to enlarge)

[5.1] Example 2 sorts Geria’s terms into four guiding categories based on their lexical fields. Within these no continua are suggested: for example “action and perception” qualities enumerated in Part IV (like swiping, hugging, tripping, and being stuck) exist along no single line.They are independent of one another, and tease us with an awareness of how utterly distinctive the patterns were for him. Those from Part II are well-distributed among the fields and reference aspects of both seen and unseen worlds. Some fit in more than one column. It is not difficult to imaginatively correlate an image of an elephant-headed fish (II.3) ornamenting a bier, or actual bathing dragonflies (II.8) with musical qualities, and we must remember that these striking images are naturalized components of Balinese thought. But it is more immediate and neutral to accept the terms from Parts III and IV, heavily weighted toward human embodiment and sensory experience, as cross-culturally pertinent music theory. Where elephant-fish is a metaphor for the instrument reyong, cajoling us to make a comparison we might not have made, swiping (IV.9) is a true analogy of wrist motion to melodic contour; indeed the contour is a consequence of the motion once one is at an instrument with mallet in hand.

[5.2] My commentaries link terms in Part IV to granular details of musical processes that neither Geria nor Bandem touch upon. In so doing I articulate a confidence that Geria would have been supremely aware of everything I hear and construe, and much more besides. Thus I habilitate him as a music analyst. How could he not be? He knew these genres, types, and patterns, and felt them deeply throughout a rich musical life, and cared enough to communicate about them. His theory, though, makes no pretense of being comprehensive or unified, though it reflects much of what is common and standardized in practice. It is an intuitively generated set of judgments about what to include and name and what to exclude, made by an expert who was a composer and performer and thought “in music.” The intuition is shaped by deeply embodied experience and habituated thought, and we should not lose sight of the ultimate particularity of each such view of the world.

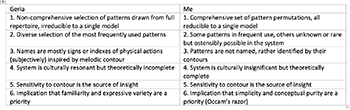

Example 3. Ubit telu (left) and ubit empat (right) shown as permutations of a single contour, XYXZ YXYZ (based on Tenzer 2000:225)

(click to enlarge)

[5.3] To introduce some cross-cultural perspective, Example 3 reproduces my typology of ubit-ubitan patterns, based also on sensitivity to contour but differently than Geria (Tenzer 2000a, 225; Tenzer 2000b). I separate ubit-ubitan into two collections, ubit telu (ubit “three”, shown at left) and ubit empat (ubit “four”, shown at right). This is such a quotidian distinction for Balinese that Geria did perhaps not even consider invoking it. In ubit telu patterns, three contiguous scale-tone pitches are used, and the polos and sangsih parts always share the middle pitch. In ubit empat a fourth pitch is added such that each part has its own two pitches, and when the low part sounds its lower pitch, the high part always sounds its higher one. This generates dyads that protrude from the texture as cross-rhythms when patterns repeat. Aside from this, though, the collections of ubit telu and ubit empat patterns are identical from the standpoint of the contours of the lower three pitches in each.

[5.4] In the large and important repertoire of “classical” pelegongan style, a significant preponderance of ubit-ubitan patterns follow a few simple rules known to all gamelan players: they last two beats at a rate of four tones per beat, and are classified either stable (ngubeng) or motile (majalan), depending on the direction of the underlying melody. For brevity, I limit the discussion to stable patterns here.(11) In search of a theoretical Occam’s razor, I also observed that successions of four tones must use all three pitches with none immediately repeated, and this must hold for all rotations of the pattern (to facilitate repetition). These constraints afford a sole “master contour” XYXZ YXYZ.(12) The columns in the two halves of Example 3 are differentiated by which of the three pitches is assigned to X: the lowest at left, the middle one in the middle, and the highest at right. The eight rows comprise rotations of the contour, yielding a total of 48 possible patterns: 24 each ubit telu and ubit empat.

[5.5] If the ubit telu/empat distinction was too generic for Geria to have even considered it viable as a basis, I was drawn to it. It was an ethnographic datum indexing a high-order concept, and to be generic is to systematically generalize—a theoretical desideratum according to what I held true. There is a problem, however, as it turns out that only fourteen of the 48 patterns generated in Example 3 (marked with asterisks) actually appear with any frequency in the repertoire, and neither I nor Balinese friends can explain why the rest are virtually absent, despite agreement that they satisfy the rules. Of this subset only five—gagulet, gagelut, nyendok, kabelet and kabelit—are in Geria’s collection too (and so labeled in the example).

Example 4. Comparison of the theories’ features and premises

(click to enlarge)

[5.6] The remainder of Geria’s patterns described in IV above are of either four or eight beats and do not conform to the two-beat template I used (there is also the anomalous gagejer, IV.6). I was fully familiar with these common longer patterns when I theorized them, but considered them instances of creativity or expressive potential within oral tradition, hence not core to a theoretical approach. Geria evidently felt he needed to include them precisely for their expressivity. He called upon his musical experience to single out what was distinctive within the familiar pool of shared resources. Exemplification, not abstraction, served his purpose. He was no more comprehensive than me, however, since his scheme omits nine patterns appearing in my typology (and numerous longer ones that neither of us touch upon) that are also common and shared. I preferred to limit my scope to something abstract that could be set out comprehensively, intentionally separating out expressive aspects of practice. Example 4 contrasts premises and features of Geria’s ubit-ubitan theory and mine, the sole shared feature (#5) being the relevance of contour.

[5.7] It is hardly surprising that there is no culturally neutral realm for theorizing, nor would we expect any two writers not to diverge significantly. Made Bandem, heir to Geria’s notebooks whose Indonesian publications infuse the translation and commentary above, was keen that Geria’s writings be placed in relation to international strains of musical thought for an English readership outside of the Indonesian (largely Javanese) musicological community with which they are in family relation already.(13) A larger context is also possible because Geria is far from alone in the wider world of music. But as we welcome many voices into an international colloquy of music theories we will be assembling a puzzle built of many such partial and evocative pieces, and are wise to minimize expectations that they will eventually fit coherently.

[5.8] Stephen Blum compares lexicons, metaphors, and categories offered by music experts of the world—Geria’s kin—as reported by the ethnomusicologists who have studied them, and concludes that consistency in lexical fields is common, but completeness is rare. And he recommends, among other things, “patience, with long-term commitment to language communities and readiness (even eagerness) to recognize and correct errors and misunderstandings” (2023, 127), adding that “Ethnomusicologists should not assume that musicians with whom we converse would prefer clear, scientifically precise concepts to the evocative metaphors of their theorizing and teaching” (99). On that point we intensify our curiosity about the many shades of theory to discover, the ways in which they will overlap and remain distinct, and the unsuspected channels their confluences will sculpt.

Michael Tenzer

University of British Columbia

School of Music

6361 Memorial Rd

Vancouver, BC

V6T 1Z2

michael.tenzer@ubc.ca

Works Cited

Bandem, I Made. 1986. Prakempa: Sebuah Lontar Gambelan Bali. Denpasar.

—————. 1992. Ubit-ubitan: Sebuah Teknik Permainan Gamelan Bali. Denpasar.

—————. 2013. Gamelan Bali Diatas Panggung Sejarah. BP Stikom Bali.

—————. 2019. Gong & Pelegongan: Jejak Historis dan Estetis Mpu Ageng I Gusti Putu Made Geria. BP Stikom Bali.

Becker, Judith. 1993. Gamelan Stories: Tantrism, Islam, and Aesthetics in Central Java. Arizona State University Program for Asian Studies.

Becker, Judith and Alan Feinstein, eds. 1984, 1987, 1988. Karawitan: Source Readings in Javanese Gamelan and Vocal Music, vols. 1–3. Center for Southeast Asian Studies, University of Michigan.

Blum, Stephen. 2023. Music Theory in Ethnomusicology. Oxford University Press.

Clampitt, David. 1997. Pairwise Well-formed Scales: Structural and Transformational Properties. PhD diss., State University of New York at Buffalo.

Geria, Gusti Putu Madé. Undated. Set of handwritten notebooks in the collection of I Madé Bandem.

Herbst Edward. 2015. Bali 1928: Lotring and the Sources of Gamelan Tradition (accompanying text to the Bali 1928 Project, vol. 3). World Arbiter.

Hunter, Thomas. 1989. Aji Ghurnita. Museum Bali. No. III c. 2390. Denpasar, Bali, Indonesia (unpublished).

Perlman, Marc. 2004. Unplayed Melodies: Javanese Gamelan and the Genesis of Music Theory. University of California Press.

Rembang, Nyoman. 1973. Gambelan Gambuh dan Gambelan-gambelan Lainnya di Bali. Kertas Kerja pada Workshop Gambuh, 25 Agustus s/d 1 September 1973.

—————. 1984/1985a. Hasil Pendokumentasian Notasi Gending-Gending Lelambatan Klasik Pegongan Daerah Bali. Proyek Pengembangan Kesenian Bali, Departemen Pendidikan dan Kebudayaan.

—————. 1984/1985b. Sekelumit Cara-cara Pembuatan Gamelan Bali. Proyek Pengembangan Kesenian Bali, Departemen Pendidikan dan Kebudayaan.

Sastrapusaka, Bendecitus Yusuf Harjamulya. [1953] 1984 . Wedha Pradangga Kawedhar [Knowledge of Gamelan Revealed]. Translated by R. Anderson Sutton. In Karawitan: Source Readings in Javanese Gamelan and Vocal Music, ed. Judith Becker and Alan Feinstein, vol. 1, 305–33. Center for Southeast Asian Studies, University of Michigan.

Steele, Peter. 2007. Innovative Approaches to Melodic Elaboration in Contemporary Kreasi Baru. MA Thesis, University of British Columbia.

Sumerta, Gede Budi, Ida Bagus Made Ludi Paryatna, and Ida Ayu Putu Purnami. 2022. “Analisis Unsur Intrinsik Dan Nilai Pendidikan Karakter Dalam Geguritan Ginal-Ginul.” Jurnal Pendidikan Bahasa Bali Undiksha 9 (i).

Tenzer, Michael. 2000a. Gamelan Gong Kebyar: The Art of Twentieth Century Balinese Music. University of Chicago Press.

—————. 2000b. “Theory and Analysis of Melody in Balinese Gamelan.” Music Theory Online 6 (2). https://www.mtosmt.org/issues/mto.00.6.2/mto.6.2.tenzer_frames.html

Tilley, Leslie. 2019. Making it Up Together: The Art of Collective Improvisation in Bali and Beyond. University of Chicago Press.

Utama, I. W. B. 2016. “The Existence and the Sustainability of the Tantrism in Bali.” International Journal of Linguistics, Literature and Culture 2 (4): 53–63.

Footnotes

1. See Herbst (2015) for a history of many people in this scene.

Return to text

2. See Becker (1993, 103–5) for Thomas Hunter’s (otherwise unpublished ) translation of part of Aji Gurnita.

Return to text

3. Becker and Feinstein (1984, 1987, 1988) present many of these early writings in translation, and Perlman (2004, 117–26) synopsizes the social conditions for music theory in early to mid-twentieth century Java. See also Rembang 1973, 1984/85a and 1984/85b.

Return to text

4. For example, at center-right (3:00 on the circle in Example 1), moving down the right column and then the left, there are seven aspects: 1): the direction is east (timur), 2) the musical tone is dang, a solmization for one of the tones of the pélog scale (this word is written in both columns for reasons I do not know), 3) dang’s sacred syllable is ksang, 4) the bodily location is the heart wherein dwells Sang Sadyojata, a manifestation of Siva (the word “Sang” as used here is an honorific for deities), 5) the deity manifested in the east is Içwara, 6) the letter is sang, eighth in the Balinese aksara alphabet, and 7) the color is white (putih). N.B.: There are inconsistencies in the mandala as a whole, as not all directions are shown as having the same number of aspects, and there are some “stray” words not clearly linked to a specific direction (see further Hunter 1989 and Bandem 1986).

Return to text

5. Geria’s selection is not comprehensive, though, as there are many common patterns not on his list.

Return to text

6. Geria’s original Balinese is retained here, quoted from Bandem (2019, 68–74).

Return to text

7. This alternative term for ngembat, from the English “octave,” is a loan word Geria probably learned when teaching in Java.

Return to text

8. Gending has many meanings, including “composition” or “piece” or even “form”; here it refers to the slower-moving structural melodic lines that most Balinese would call pokok or bantang.

Return to text

9. In addition to the commentary on my own prior publication addressing this topic, offered at the end of this article, see also Steele (2007, 41–43) for more consideration of Geria’s collection discussed here.

Return to text

10. A search yielded a sole occurrence of babaru in a citation of geguritan (an important genre of Balinese poetic song) describing a (metaphorical) horse ridden into battle to defeat the demons within the self (Sumerta et al. 2022). Correspondence with one of the article’s authors suggests defining it as a religious/spiritual guide whose teachings can be used as a whip to subdue these demons (Gede Budi Sumerta, email of February 27, 2023). Bandem concurs, but Geria was mum.

Return to text

11. See fuller discussion in Tenzer (2000a, 220–31).

Return to text

12. The swapping of X and Y in relation to the stable Z in the two halves of the pattern is an example of David Clampitt’s “pairwise symmetry” (1997, 2–4). Thanks to Rick Cohn and Leigh van Handel for this insight.

Return to text

13. Dissemination of Geria’s classifications and their currency in Bali itself is uneven. Some teachers at the conservatory introduce them in class, and some musicians in village contexts encounter them informally, perhaps through networks tracing to Bandem, his writings, or his colleagues. But there is little reason or need for practicing musicians to use them in the context of rehearsal or performance. In villages the learning of traditional repertoires such as those Geria addressed remains, as ever, oral and rote.

Return to text

Copyright Statement

Copyright © 2024 by the Society for Music Theory. All rights reserved.

[1] Copyrights for individual items published in Music Theory Online (MTO) are held by their authors. Items appearing in MTO may be saved and stored in electronic or paper form, and may be shared among individuals for purposes of scholarly research or discussion, but may not be republished in any form, electronic or print, without prior, written permission from the author(s), and advance notification of the editors of MTO.

[2] Any redistributed form of items published in MTO must include the following information in a form appropriate to the medium in which the items are to appear:

This item appeared in Music Theory Online in [VOLUME #, ISSUE #] on [DAY/MONTH/YEAR]. It was authored by [FULL NAME, EMAIL ADDRESS], with whose written permission it is reprinted here.

[3] Libraries may archive issues of MTO in electronic or paper form for public access so long as each issue is stored in its entirety, and no access fee is charged. Exceptions to these requirements must be approved in writing by the editors of MTO, who will act in accordance with the decisions of the Society for Music Theory.

This document and all portions thereof are protected by U.S. and international copyright laws. Material contained herein may be copied and/or distributed for research purposes only.

Prepared by Andrew Eason, Senior Editorial Assistant

Number of visits:

3792