Analyzing Difference in Recordings of Bach’s Violin Solos with a Lead from Gilles Deleuze *

Dorottya Fabian

KEYWORDS: Performance style, individual difference, violin, J.S. Bach, Deleuze, historical performance practice, performance analysis

ABSTRACT: Through a case study of recordings of Bach’s Sonatas and Partitas for Solo Violin, I argue that enlisting Deleuzian concepts when analyzing multiple performances of the same piece is useful for the exploration of individual differences and practices of performance. Such analysis reveals a continuously shifting-transforming performance style and provides a rich tapestry of diversity within and across nominally agreed upon stylistic trends and characteristics such as Romantic-modernist, Classical-modernist, or historically informed.

Copyright © 2017 Society for Music Theory

[0.1] Since at least the 1990s some researchers have pushed for a revisionist approach to musicological thinking regarding the ontology of musical works in the Western classical tradition (Goehr 1992) and for a reconsideration of the respective roles composers and performers (as well as listeners) play in constructing the identity of compositions (Cook 2001, 2012; Leech-Wilkinson 2012). In this revisionist thinking the score is merely a script for the musical imagination and the “meaning” is created in the act of performing, listening, reading or analyzing. A focus on these possible realizations has enabled researchers to map significant trends in the history of interpreting notated compositions (Cook 2014; Fabian 2003; Leech-Wilkinson 2009a, 2009b; Philip 1992, 2004). But if we are serious about questioning the identity of musical works and paying attention to the myriad possible instantiations of score-scripts, we cannot be satisfied by noting only major historical characteristics. We must find ways to account for nuanced differences—differences that exist not only across multiple performances but are also internal to the music because of its transience, because it is a temporally unfolding eventful process.

[0.2] While machine learning and big-data mining can fast-track the identification of general norms and trends (Crawford and Gibson 2009), individual listeners’ snail-pace systematic and comparative study of sound recordings makes them sensitive to these micro-variations within and across particular performing styles, enabling an interrogation of the nature of music in performance.

[0.3] In this paper I explore how we might trace and analyze difference in music performance. Focusing on recorded performances of J.S. Bach’s Six Sonatas and Partitas for Solo Violin (henceforth the Solos), I examine documented, theorized stylistic conventions. I show that far from being neat categories, performing styles and precepts are constantly shifting, largely imperceptibly, through the coming of age of ever newer generations of musicians creating micro-traditions and practices of performance. A non-dialectical, non-identity-based mode of thinking can account for these variations. I propose that thinking of “the music” as emergent and virtual in the Deleuzian sense is helpful. Enlisting Deleuzian concepts such as differentiation versus differenciation assists the elucidation of difference per se, while terms like molar lines, molecular lines, and lines of flight help explain differences in degree as well as in kind. In other words, Deleuzian thinking helps us see a single musical utterance's internal difference-from-itself and the work as it exists across multiple performances (Deleuze 1994; Deleuze and Guattari 2012). It helps to distinguish one instantiation of the composition from another along a vector, or rather, the multi-dimensional space of performance styles, all contributing to the multiplicity that is the embodied experience of “the work” as it lives in a listener’s (analyst’s, performer’s) memory of performances, score study, and other exposures.

1. The tools – Deleuze’s philosophy of difference

[1.1] To enable the analytical discussion, I start by explaining the theoretical framework and descriptors I will call upon to unpack the ongoing process of differenciation (see below) that defines “the work” across a multiplicity of performances, as well as variations in stylistic characteristics and non-linear interactions of performance features in the actualizations of “the work.” My aim is to engender a different type of thinking by enlisting a Deleuzian conceptual framework and concomitant terminology. Their relevance and enabling power are demonstrated through the ensuing analytical discussion.

[1.2] As we leave behind the belief that the score is the work—that a performer simply performs the symbols notated by the composer and so the work reveals itself categorically—and instead acknowledge that we, as well as artworks, are multiplicities, that more than one thing can be true at once, we realize the need to have new ways of talking about performances. We need an approach that eludes categorical or normative thinking and goes well beyond binary opposites such as spontaneous flexibility versus literal consistency, historically informed versus mainstream, artistic integrity versus capricious mannerism, being true to the score versus imposing subjectivity and vanity, and so on.

[1.3] I posit that because of its emphasis on pluralism, Deleuzian philosophy can be usefully mobilized to engage with the web of interrelations that make up a musical performance. Deleuze’s philosophy of difference is not about identity and representation. It denies the “primacy of original over copy, of model over image” (Deleuze 1994, 66). Deleuze critiques the view that subordinates “difference to instances of the Same, the Similar, the Analogous and the Opposed” (1994, 265) or “to the identity of the concept” (1994, 266). If we agree that the score is not the Work but only an aspect of the work in its virtual state, and that instantiations of it are actualized in an infinite number of performances, then it is possible to think of the Work (the Idea) not as a singular, categorical entity (identity) but as a multiplicity, an emergent, constantly transforming process manifesting in transient assemblages aka performances.(1)

According to Deleuze,

Ideas are multiplicities: every idea is a multiplicity or a variety.

. . . [M]ultiplicity must not designate a combination of the many and the one, but rather an organization belonging to the many as such, which has no need whatsoever of unity in order to form a system.. . . ‘Multiplicity’, which replaces the one no less than the multiple, is the true substantive, substance itself.. . . An Idea is an n-dimensional, continuous, defined multiplicity (1994, 182).

Together with Felix Guattari, they posit that “becoming and multiplicity are the same thing. A multiplicity is defined

[1.4] For Deleuze, Ideas are virtual and “are actualised by differenciation” (1994, 279). While differentiation “determines the virtual content of an Idea as problem,” differenciation actualises this virtuality “into species and distinguished parts” (207). Since each “expresses the actualisation of this virtual and the constitution of solutions” (209), we can think of performances as differenciations, as “sites for the actualisation of Ideas” (278). But how do these differeniciations relate to each-other?

[1.5] In his work with Guattari, Deleuze introduced the term Body without Organs (BwO), also called (or at least related to) the plane of immanence or plane of consistency. This, they posited, is “the unformed, unorganized, nonstratified, or destratified body and all its flows: subatomic and submolecular particles, pure intensities, prevital and prephysical free singularities” (Deleuze and Guattari 2012, 50). The BwO “becomes compact or thickens at the level of the strata” for strata are “acts of capture,” they “consist of giving form to matters, of imprisoning intensities” (46).

[1.6] Since the “plane of consistency is a plane of continuous variation” (2012, 594), I would like to argue that we can think of music performance as a kind of free-flowing plane of immanence or body without organ that thickens into layers (i.e. strata) as the actualization takes shape through differenciation. The process of actualization involves the milieus, for “each stratum

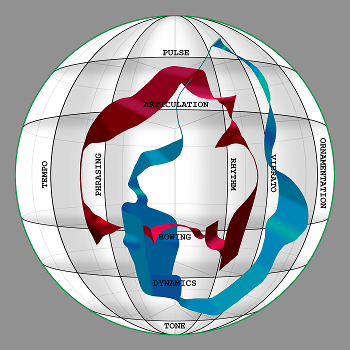

Example 1. Diagram of Strata, Milieus and Territorialized styles of Baroque music performance

(click to enlarge and see the rest)

[1.7] I identify Deleuze and Guattari’s territory with performance style because it is where “the originally separate elements from the varied milieus [i.e. the various coded and/or de-coded performance features] are

[1.8] To unpack these processes three additional terms need to be introduced from Deleuze and Guattari’s toolbox. In A Thousand Plateaus, they discuss three “lines” in relation to strata (i.e. “phenomena of thickening”; 2012, 584, 46), assemblages (“extracting a territory from the milieus”; 585)) and rhizome (a heterogeneous, non-linear chaotic system that “connects any point to any other point”; 21)). The three lines are: (i) the “molar lines” (or lines of rigid segmentarity) that “ensure and control the identity of each agency” (229); (ii) the “molecular lines” (or lines of supple segmentation) that “are simultaneously present and imperceptible

[1.9] These three concepts are important for the analysis of the interpretations, and of the micro-variations that underlie the differenciation each performance actualizes. As stated earlier, differenciation starts when the potential (abstract) performance parameters (a.k.a. pure intensities) start to sediment into articulable performance features and gradually take on a stylistic code as they thicken at the level of strata. Deleuze and Guattari speak of a “double articulation

The first articulation is the process of “sedimentation”. . . The second articulation. . . sets up a stable functional structure.. . . each articulation. . . possesses both form and substance. . . one type is supple, more molecular, and merely ordered; the other is more rigid, molar, and organized.

In this case, a performer selects particular elements (tempo, bowing, dynamics, articulation, etc.) and makes decisions regarding their execution (Examples 2–3). The difference among performances lies in the subtle variations in the choices of important performance features (content) and their execution (expression) because “what varies from one stratum to another is the nature of [the real distinction between content and expression],” the nature of the double articulation (66). Since “content and expression are not distinguished from each other in the same fashion on each stratum

[1.10] Importantly, Deleuze and Guattari also emphasize that

the line of flight does not come afterward; it is there from the beginning, even if it awaits its hour, and waits for the others to explode. Supple segmentarity, then, is only a kind of compromise operating by relative deterritorializations and permitting reterritorializations. . . and reversions to the rigid line. It is odd how supple segmentarity is caught between the two other lines, ready to tip to one side or the other; such is the ambiguity (2012, 240).

The lack of symmetry among the lines enables “the masses and flows” to constantly escape and invent new connections” (588).

[1.11] In summary, features (i.e. formed substances and coded or decoded milieus) of performances are like molar and molecular lines and lines of flight that contribute to different assemblages by extracting transient and overlapping stylistic territories (strata). Some features are “propelled toward a rigid segmentarity” (Deleuze and Guattari 2012, 231) and territorialize while others “introduce a current of suppleness” (230) that deterritorialize the particular stylistic characteristics, occasionally leading to a “clean break,” a radically differenciated reading, or an arguably idiosyncratic one that may manifest “absolute deterritorialization” (234). In the flux of forces that swirl around in music performance, molar lines are elements (sediments) that define a performance style, i.e. a territory. They segment and territorialize; they make a performance belong to a type (the “One”). Molecular lines are features that weaken the territory. They create “cracks” blurring style categories. They deterritorialize and may contribute to the transformation of style or just the weakening of the territory. Lines of flight are those elements of a performance that create radical departures from the usual. If they predominate, the style is completely deterritorialized and the performance may be perceived as idiosyncratic or mannered.

[1.12] The concepts explored in this exposition are essential in helping to dislodge our conventional approach to the study of difference in performance. Being new terms, they resist our ingrained dialectical and categorical thinking. They assist us in hearing the interactions of performance features as well as other contributing factors, in seeing the multi-directional, non-hierarchical connections of diverse layers of micro-variations. This, in turn, provides a window into differences within broader stylistic practices and a more nuanced understanding of the ephemerality and uniqueness of each individual instantiation of “the Work”. It may even foster a pluralistic approach to understanding practice – an approach that focuses on the relationship among performances rather than between performance and score, or between performance and stylistic trends.

2. Performing traditions and ideologies

[2.1] Many scholars have theorized how traditions of performing Baroque music have developed over the course of the past one hundred years or so (e.g. Taruskin 1995, Butt 2002, Haynes 2007), and even more information is available regarding the characteristics of conventions in particular historical periods (e.g. Philip 1992, 2004; Stowell 1992; Neumann 1993; Lawson and Stowell 1999; Milsom 2003; Peres Da Costa 2012). My aim is to cut through the established categories and show performance practices to be less period-specific and more dynamic and constantly emerging; to show that performance is a process where forces (becoming molar / becoming molecular) swirl, thicken, territorialize and deterritorialize in a constant flux. My case study concerns recordings of Bach’s Six Sonatas and Partitas for Solo Violin, BWV 1001–1006 (henceforth the Solos) made since the 1950s. On the basis of extensive familiarity with over sixty complete sets, I have selected particular movements and performers to show how a Deleuzian approach can aid the analysis of performance per se. Such an approach seems particularly suitable to this repertoire for two main reasons: Firstly, the Solos have a long, illustrious, fairly well-documented performance history (Lester 1999; Fabian 2005, 2015) with dozens of recordings from 1903 onwards; and second, because studying performances of a piece from the Baroque period enables engagement with specifically theorized stylistic categories: the vitalist or Romantic-modernist (RMP), the literalist or Classical-modernist (CMP), and the historically informed performance (HIP) styles. To appreciate my argument for constantly shifting and emergent rather than periodically changing and categorical performance styles, we need to become familiar with the characteristics of these three theorized practices.

The “vitalist” or Romantic-modernist (RMP) approach

[2.2] This style of performing Bach’s music originates in nineteenth-century ideologies and aesthetics and relates to a reverential Bach image. It places a premium on Bach the composer of contrapuntal organ and vocal works for the Lutheran Church, on devout and serious sentiments. It regards Bach as “the beginning and end of all music” (Max Reger, cited in Anderson 2006, 82). The appropriate performing style is ponderous, sustained, and slow-moving; each note is played with equal importance and seriousness. The best evidence for the strong conviction regarding the validity of such an approach to the music is the so-called Bach-bow, promoted by Albert Schweitzer in the 1930s and used by Emil Telmányi in the 1950s and Rudolf Gähler on a recording made in 1997 (Schweitzer 1950b, 1950a, Telmányi 1955; for more sources see note 26 in Fabian 2005). It is a curved bow that enables the player to play all four strings of the violin at once. It was invented precisely because the notated polyphony of the Solos could not be played in a sustained style without it.

Audio Example 1. Bach Partita in D minor, BWV 1004, Ciaconna, measures 1–8, performed by Telmányi with a curved bow in 1955

[2.3] On listening to recordings made with such a curved bow, the organ-like quality of the sound is immediately striking (e.g. Audio Example 1). But although the historical existence of such a special bow was discredited by the early 1960s, and it is quite common for violinists to make disparaging jokes about it, the style of interpretation it was supposed to aid has not gone out of fashion; not completely even today. The “serious Bach” trope can be heard on many versions, mostly from the 1940s to the 1980s (e.g. Menuhin 1936, 1957; Heifetz 1952; Perlman 1988), but also on some recordings made at the turn of the century (e.g. Hahn 1997, Ehnes 1999, Fischer 2005, Khachatryan 2010). This style of playing has been variously labeled “canonical” (e.g. Haynes 2007) or “vitalist,” (e.g. Taruskin 1995) but also “mainstream,” more generally. To differentiate it from other approaches also often labeled “mainstream” (see below), I refer to it as the “Romantic-modernist performance” (RMP) style, following John Butt’s lead.(2)

[2.4] The Romantic-modernist approach to music performance is characterized by a generous use of vibrato, sustained and seamless bowing where the change from up- to down-bow is not noticeable, phrasing that projects long melodic lines, aided by the ebb and flow of dynamics, rhythm that tends to be literal, and ponderous tempos. In Deleuzian language these could be the molar sedimentations of the assemblage that segment and territorialize, that “ensure and control the identity” (Deleuze and Guattari 2012, 229) of what is labeled Romantic-modernist performance. Crucially, the RMP approach does not shy away from “heartfelt” expression, of interpreting-invigorating-enlivening the score (hence the label “vitalist” used by Taruskin 1995, 108–10). This may be achieved through tone (vibrato, bow pressure and speed) or pointing up climactic moments through timing and tempo flexibility as well as dynamics, or through other “liberties” not notated (e.g. dramatic increase or decrease of tempo, extreme range of basic tempo, asynchrony and a hierarchical relationship between melody and accompaniment, etc.). In other words, certain abstract substances (generic performance parameters) that swirl around as molecular (supple segmentarity) tip towards rigidity, the molar of the Romantic-modernist style (Deleuze and Guattari 2012, 230, 240).

The “Literalist” or Classical-modernist (CMP) approach

[2.5] Parallel to the serious-Romanticized view of Bach, a counter-image has also been developing that gained momentum around the 1930s, eventually branching into two directions from the 1960s onward. This counter-image prioritizes making Bach’s music sound Baroque and stripping from it the Romantic veneer. Among musicians in this camp are those who aim to reduce what they consider emotional excesses in expression, and instead emphasize the repetitive motor rhythms, playing them fast and with clockwork-like evenness. Because of its sleek and undifferentiated tendencies, this approach has been labeled “modernist”; to distinguish it from other twentieth-century (i.e. modern) approaches such as the Romantic-modernist, researchers have added the adjective “Classical” to reflect its (neo-)Classicistic traits (Butt 2002).

[2.6] Other musicians have also aimed at de-Romanticizing the performance of Baroque music, but considered it essential to use period instruments and to study all sorts of historical sources, especially instrumental treatises. For a long time the performance styles of these two groups was not differenciated much, but eventually the subtle molecularity of period playing techniques among other parameters has started to create cracks tipping towards lines of flight causing rupture and allowing a new sound (absolute deterritorialization) to emerge, identified as historically informed performance or HIP (discussed in the next section).

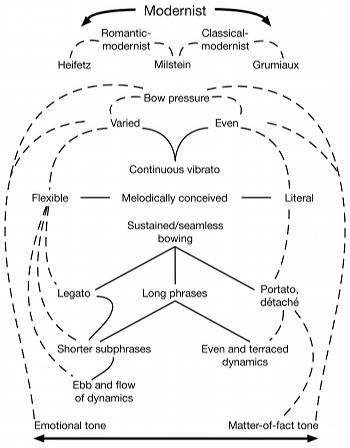

Example 2. Schematic diagram of the modernist performance space and its dimensions

(click to enlarge)

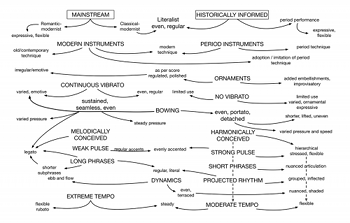

Example 3. A schematic two-dimensional summary of “mainstream” versus “historically informed” performance characteristics (molar lines)

(click to enlarge and see the rest)

[2.7] Capturing its essentially literal reading of notation and motoric projection of rhythm, the CMP approach has also been labeled “sportive,” “geometric,” or “sewing-machine” style (Fabian 2003; Taruskin 1995; Dreyfus 1983). Its described characteristics include steady tempo, inflexible rhythm, and homogenous dynamics; use of even, portato bow-strokes; a focus on melody lines “played on a single string as much as possible” for evenness of timbre; “not adding ornaments; and playing with regular accenting,” and with evenly calibrated vibrato on every note (Fabian 2015, 100).

[2.8] In dualistic discussions of twentieth-century Bach performances both the RMP and the CMP approaches are often simply labeled “mainstream,” as opposed to HIP. Yet we can already see crucial differences between them (Example 2). These differences reflect further molar and molecular lines, variations in aesthetic orientation rooted in shifting cultural and historical understanding. The main common dimension that RMP and CMP seem to share—and the reason why both are generally referred to as “mainstream”—is the conviction that the stylistic requirements of the composition’s performance survive in a living tradition, handed down by a succession of great masters, teachers, and performers. However, as the analyses will show, what this “living tradition” might be, what shape and form the musician gives to the work, which of its dimensions emerge, and what forms and substances are articulated through differenciation varies infinitely, undermining the very concept.

[2.9] But that is not the only problem with these theorized categories. The new HIP style branching out from CMP, as explained above, further indicates the fluid nature of performance style. The common aim to de-Romanticize Bach’s pieces and return to playing them in a Baroque style opened additional doors (e.g. through the use of period instruments and instrumental technique), leading to further differenciations and a third theoretical category, the specimen of which displays overlaps not just with CMP but also RMP (Example 3).

The Historically-Informed (HIP) Approach

[2.10] The characteristics of the style of performance we have come to call HIP stem from the adoption of period instruments and instrumental techniques. Additionally, performers specializing in HIP study historical treatises and other archival sources to gain a better understanding of the culture and aesthetic preferences of the time and the composer’s surroundings. The currently established features of HIP include a foregrounding of harmony rather than melody; strong projection of pulse; closely articulated small motivic cells; rhythmic inflections and timing flexibilities; varied, short and lifted bow strokes that create rapid note decay and a constant fluctuation and nuancing of dynamics within a basic volume; arpeggiation of multiple stops; lively and bouncing dance movements; moderate basic tempos; and the addition of ornaments and embellishments (Fabian 2015, 104).

[2.11] As this list indicates, HIP may sound anything but literal or clockwork-like, yet according to conventional narratives, it grew out of and still largely represents the Classical-modernist approach (Taruskin 1995). A Deleuzian lens may show instead HIP’s place at the tension between CMP and RMP. As I will show, some of the features may even imply that HIP might sound closer to RMP, or that RMP may have subtle molecular segments that could be tipped towards HIP. Close listening can tease out the differenciations of each performance feature to unveil the overlaps of stylistic territories and their layers (Examples 2–3), indicating that the descriptive terms are also transient, constantly exceeding themselves and reconstituting their meaning according to context.

[2.12] In this necessarily brief and general overview I have outlined major differences in assemblage and described three strata of coded milieus that ground broad stylistic categories: Romantic-modernist, Classical-modernist, and historically-informed. However, the account also pointed at grey areas, overlaps, and the blurring of types, and it implied the constant coding and decoding (territorializing and deterritorializing) of milieus. In fact Deleuze’s philosophy urges us to discard categories and think instead of processes of becoming, of becoming-molar. “Becomings are molecular” while categories are molar (Deleuze and Guattari 2012, 341). The becoming-molar is the process toward sedimentation or reification into a type. We should think of music performance as enacting this sedimentation, this drawing of a context on the plane of immanence by territorializing milieus. Thinking in monolithic categories like Classical-modernist or HIP is to surrender to arborescent thought (centralized, hierarchical, dependent on “signification and subjectification” (16), to the historical account propagated by “the state” (a.k.a. musicological authority).(3) Performance styles and conventions shift gradually and imperceptibly, because music is emergent, providing musicians with considerable room to carve out unique interpretations even within established norms. The age of the artists and their training—the aesthetically and technically formative years of their musicianship—tend to set molar lines; the molecular lines they adopt are not always strong enough to become lines of flight and radicalize the style. But they are there, “simultaneously present and imperceptible

3. Differences within and across traditions

[3.1] I start my analyses of performances by looking at interpretations from the middle of the twentieth century, representing the Romantic-modernist and Classical-modernist approaches. This will be followed by a discussion of recordings made by pioneers of HIP, to show where and how deterritorialization of these “mainstream” styles has occurred. After that I discuss differenciations within the HIP style and across subsequent actualizations recorded by the same violinists. Finally, I comment briefly on one additional version that I consider to be one of the most idiosyncratic readings exemplifying the “in-between,” “rhizomic” nature of classical-music performance.

Mainstream twentieth century styles: RMP and CMP in motion

[3.2] Two of the most iconic violinists of the twentieth century are Jascha Heifetz (1901–1987) and Nathan Milstein (1903–1992). They both studied with Leopold Auer in St Petersburg: Heifetz from age 9, Milstein from age 12, having previously trained with Pyotr Stolyarsky in Odessa. They also both immigrated to the US, Heifetz becoming a citizen in 1925, Milstein in 1942. Importantly, they both performed the Bach solo sonatas and partitas throughout their careers and made recordings of them around the same time. Heifetz recorded the complete set only once, in 1952. Milstein did so twice, in 1955–56 and in 1973. Heifetz’s and Milstein’s recordings have been compared by Fabian and Ornoy (2009). They noted several differences between the respective versions but judged them all to be displaying aspects of the normative, “mainstream” style.

Audio Example 2a. Bach Sonata in A minor, BWV 1003, Andante, measures 1–12, performed by Heifetz

Audio Example 2b. Bach Sonata in A minor, BWV 1003, Andante, measures 1–12, performed by Milstein

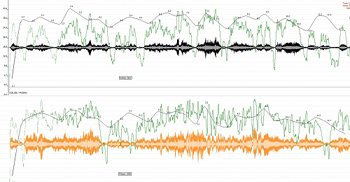

Example 4. Tempo and dynamic curves in Heifetz 1952 (top panel) and Milstein 1956 (bottom panel) recordings of Bach Sonata in A minor, BWV 1003, Andante, mm. 1–12

(click to enlarge and listen)

[3.3] Building on Fabian and Ornoy’s work, we can make further comparisons of Heifetz’s and Milstein’s mid-century recordings of the Andante movement from the Sonata in A minor, BWV 1003. The tempos are very similar (ca. 28 beats per minute for Heifetz and ca. 29 bpm for Milstein), rhythm is literal and phrasing is long-ranged, aided by arching dynamics. The vibratos are continuous with similar depth (ca. 0.5 semitone for Heifetz and 0.4 sT for Milstein), but Heifetz’s is faster than Milstein’s (6.8–7.3 for Heifetz versus 5.3–6.5 for Milstein). Sound quality also differs, partially due to differences in recording technology and restoration and digitization processes, and partially to Heifetz’s and Milstein’s different instruments and techniques (e.g. bowing, vibrato). We can observe a greater role of dynamics in Heifetz’ phrasing; his performance has many small dynamic arches while Milstein’s is more even with a forward motion (Audio examples 2a and 2b, performed by Heifetz (1952) and Milstein (1955)). The more frequent fluctuation of dynamics in Heifetz’s recording can be clearly seen in the screenshots from the audio analysis program Sonic Visualiser (Cannam et al. 2010), which shows dynamic arches every two bars or so (Example 4). In contrast, Milstein creates one longer phrase from measures 4–5 to the end of the first half, with only a momentary dip around measure 8, before the final cadential flourishes in measures 9 and 10. Essentially, the graph shows that the difference between their versions, the articulation of phrases, is achieved primarily by dynamics and not tempo modifications. While their tempo lines are similarly fairly even, Milstein’s dynamic curve shows essentially two (measures 1–5, 5–11) or perhaps three arches (measures 1–4, 5–8 and 9–11), whereas the dynamics in Heifetz’s version articulate smaller units (measures 1–2, 2–5, 5–7, 7–8, 8–9, 9–11).

Example 5. Spectrogram of Bach Sonata in A minor, Andante, m. 17 in Heifetz’s 1952 recording (top) and Milstein’s 1956 recording (bottom)

(click to enlarge and listen)

Audio Example 3. Bach Sonata in A minor, Andante, measure 17, performed by Heifetz and Milstein

[3.4] In addition to phrasing through dynamics, Heifetz’s playing demonstrates the “Romantic-modernist” style also through his legato articulation. He tends to hold notes over rests, making the melody line sound more sustained in spite of the drop in dynamics. He also underplays the accompanying notes, focusing on the melody. The spectrogram of measure 17 illustrates this (Example 5): the accompanying double stop (

[3.5] In contrast, Milstein plays all notes with equal dynamics and vibrato, articulating the accompanying voice much more clearly. However, like Heifetz, his bowing is sustained with minimal articulation of the repeated high C of the melody (bottom of Example 5).

[3.6] Although both represent mainstream Romantic-modernist performing conventions, there are also considerable differences between these recordings, which were made only four years apart. The differences noted indicate that although they are close contemporaries and have a shared cultural-educational background, Heifetz’s playing seems to contain molecular lines that tip his modernist approach towards the Romantic-modernist style; stabilizing the molar sedimentarity of Romantic expression and aesthetics (Example 2).

[3.7] Milstein’s less Romantic sound (narrower and more even vibrato, no slides, less fluctuation of dynamics) on the other hand, signifies a flow towards the Classical-modernist approach and indicates that performance style is a continuous vector rather than a collection of distinct types. This can further be shown by a brief comparison of his second recording of the complete set (1975) with Arthur Grumiaux’s (1921–1986) from 1962. Further differenciations in assemblages of Romantic-modernist molar sedimentation are discussed by Fabian and Ornoy (2009).

[3.8] Both Grumiaux and Milstein take the fugal and fast movements at average tempi (as indicated by their very low standard deviation values when compared to ca. fifty other recordings made since 1903, Fabian 2005) with standard détaché bowing. In faster movements, Milstein often chooses a slower tempo than in 1956, closer to Grumiaux’s. In slower movements the trend is the opposite; he plays faster in 1973 which again is closer to Grumiaux’s recording (see Examples 6–7). The Classical-modernist aesthetic of downplaying both the emotional-expressive and the virtuosic dimensions of the music can be observed here: no extremes are allowed, as they are regarded as “Romantic” gestures. The two violinists have a similar approach to the Allemandes and most other dance movements as well—i.e. the pulse is moderately perceptible—although Milstein’s at times sounds heavier and broader than Grumiaux’s.

Example 6. Average tempos in Sonata movements (click to enlarge) | Example 7. Average tempos in Partita movements (click to enlarge) |

Audio Example 4a. Bach Partita in D minor, Sarabanda, measures 1–8, performed by Grumiaux

Audio Example 4b. Bach Partita in D minor, Sarabanda, measures 1–8, performed by Milstein

[3.9] A brief comparison of Grumiaux’s and Milstein’s reading of the Sarabanda from the Partita in D minor, BWV 1004 may illustrate these observations (Audio examples 4a and 4b, performed by Grumiaux (1962) and Milstein (1975)). In this movement Grumiaux plays much faster than average (SD 1.63). His tone is clear but somewhat intense because his vibrato is on the faster side, which is particularly noticeable on quarter notes and longer notes, when it becomes wider. He interprets rhythm fairly literally, with hardly any flexibility or grouping, and his articulation reflects the sustained style, with longer phrases shaped through slight crescendos and decrescendos, especially in the second half of the movement. Overall, his playing sounds rather rushed and matter-of-fact, with one basic dynamic level, a steady tempo, and a moderately intense tone, but with some obvious, easy-to-perceive phrases. Milstein’s playing is slower and more intense, especially during repeats. His bowing is much more sustained, with heavier pressure and long even strokes, but he varies the tempo and dynamics more. His vibrato is more noticeable than in the 1956 recording even though the measured average rate and depth have not changed much. He performs rhythmic groups with more flexibility than Grumiaux. Although Milstein also projects longer phrases, he introduces slight agogic stresses and shapes the music with a stronger ebb and flow of tempo and dynamics, creating more detail and sounding more expressive. Milstein’s recording thus shifts between layers of becoming stratified CMP and becoming open to flows of RMP sedimentation.

Example 8a-b. Variation in tempo and dynamics in Grumiaux’s 1962 and Milstein’s 1975 recordings of the Sarabanda movement from Bach Partita in D minor, BWV 1004

(click to enlarge and see the rest)

[3.10] Example 8a and 8b illustrate these observations: they show the collapsed tempo and volume fluctuations of the two violinists averaged across the repeats. Example 8a captures the first half of the movement, example 8b the second half (without the coda). In measures 1–8 repeated, Grumiaux’s dynamics line is more even while his tempo line moves in a narrower range than Milstein’s. Even so, it is clear that both create two phrases (measures 1–5 and 5–8) through dynamic and tempo arches. This large-scale phrasing is also in evidence in the second half of the movement. Example 8b shows this clearly, as well as the greater tempo fluctuation used by Milstein. Grumiaux relaxes the tempo only for cadence points while Milstein shapes sub-phrases through more frequent micro-variations.

[3.11] Importantly, Milstein uses a more sustained bowing than Grumiaux. This can be seen when inspecting spectrograms of their respective audio files (not shown). The somewhat quicker decay of partials in the spectrogram of Grumiaux’s recording reflects a slightly less “overheld” or sustained bowing; longer notes taper off and allow for slight gaps in the signal before the subsequent notes or chords are attacked.

[3.12] Summarizing the above observations, I would argue that both are “literal” readings and conceive the sarabande melodically. But while Milstein uses longer, more even bow-strokes, Grumiuax chooses a fast tempo and a slightly more detached articulation. They both create longer phrases (usually of four measures) with Milstein exploiting a greater range of dynamics and tempo fluctuation than Grumiaux. Milstein’s choices push the literalist, Classical-modernist type towards the Romantic-modernist and make his version sound more expressive. In Grumiaux’s case the fast tempo overrides everything, becoming a line of flight that deterritorializes the sarabande character. The interpretation is not simply literalist, it is almost caricature.

The emergence of a new stylistic territory: CMP and HIP in motion

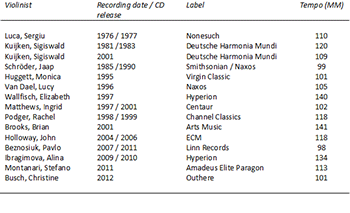

[3.13] How much ground the literalist, Classical-modernist approach had gained by the second half of the twentieth century can be further observed when comparing the recordings of two pioneers of the historically informed performance style: Jaap Schröder and Sigiswald Kuijken. They both represent musicians who were at the vanguard of HIP during the 1970s. Schröder is considerably older (born in 1925) yet recorded the Solos only in 1985, later than Kuijken (born in 1944), whose first version was recorded in 1981 and issued a year later. Kuijken made a second recording of the set in 2001, but my discussion focuses on the earlier version.

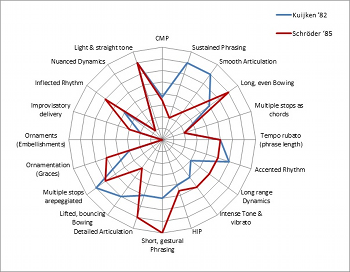

Example 9. Diagram showing the relative contribution of HIP (left side) and CMP (right side) features to the overall style of Kuijken’s and Schröder’s recordings of the Solos

(click to enlarge and see the rest)

[3.14] At the time of release they may have sounded more radical, but in hindsight both interpretations display signs of “mainstream-canonical” heritage (Example 9). In terms of bowing, articulation, ornamentation, rhythmic projection, tone, dynamics and the delivery of multiple stops, both recordings sound fairly “in-between” Classical-modernist and HIP. Schröder plays with hierarchical accents, grouping rhythmic patterns according to meter and pulse. Kuijken’s articulation and bowing is more even and regular. However, both of them often revert to mechanical accenting that leads to a motoric and monotonous delivery instead of a bouncing, dancing one. In Schröder’s case the slower tempos exacerbate the effect. They both tend to arpeggiate chords slightly but their vibratos are almost continuous and their bowing not too lifted. This limits micro-variations in dynamics and fosters homogeneity; volume is varied only when terraced dynamics are prescribed in the score.

[3.15] Detailed scaling of their recordings along all performance variables (milieus) coded according to theorized CMP and HIP characteristics (molar sediments) shows somewhat higher scores on CMP dimensions (especially in Kuijken’s case), with arpeggiation of multiple stops and a lighter tone being the strongest HIP elements (Example 9). Schröder’s recording also rates highly on the HIP scales “Inflected rhythm” and “Short, gestural phrasing.” In contrast, Kuijken scores highly on the CMP scales “Sustained phrasing” and “Smooth articulation.” Especially noteworthy in relation to my argument regarding the overlapping of styles is the fact that Schröder scores highly not only on “Short, gestural phrases,” an HIP characteristic, but also on “Long, even bowing,” a dimension that is molar in CMP style. Neither of the recordings has much ornamentation and both players score fairly low on the “improvisatory delivery” scale, a key feature of HIP. All these territorializing and deterritorializing shifts are summed up in their respective overall scores for CMP and HIP, which are both moderate.

Audio Example 5a. Bach Partita in E major, BWV 1006, Gigue, measures 1–16, performed by Schröder

Audio Example 5b. Bach Partita in E major, BWV 1006, Gigue, measures 1–16, performed by Kuijken

[3.16] To look at specific examples, we can turn to their respective recordings of the Allemanda from the Partita in D minor and the Gigue from the Partita in E major, BWV 1006. These show both violinists starting out in the HIP style, articulating harmonically and metrically governed groups of figurations. Kuijken’s lighter and shorter bowing, lesser vibrato and increasingly smoother (and faster) playing that progressively relies more on accents rather than timing stresses soon (from about measures 3–4) creates a diverting sound world. The timbre becomes thin, the dynamics consistent without fluctuating shades, the accents too predictable, especially in the Gigue. Schröder’s broader yet varied bowing and more spacious tempo, on the other hand, allow for greater nuance, agogic stresses, and timing flexibilities. These hold the listener’s attention, which easily follows the harmonic progressions and closely articulated motives. Thus the reading avoids sounding monotonous; instead it is perceived as expressive in a historically informed way. Kuijken’s accentual approach is even more obvious in the E major Gigue, which sounds rather predictable and regular; in other words, Classical-modernist rather than HIP (Audio examples 5a and 5b, performed by Schröder (1985) and Kuijken (1983)).

Audio Example 6a. Bach Sonata in G minor, BWV 1001, Presto, measures 1–54, performed by Schröder

Audio Example 6b. Bach Sonata in G minor, BWV 1001, Presto, measures 1–54, performed by Kuijken

[3.17] The Presto movement from the Sonata in G minor, BWV 1001 shows that both of these performers can indeed be very close to the Classical-modernist style that reduces such fast movements to the status of mere exercises. In Schröder’s performance, the slow and unwavering tempo, even bowing, consistent dynamics, and predictable downbeat accents form the molar lines territorializing the CMP style. Kuijken’s faster tempo and thinner tone bring about molecular sedimentations that could tip the reading towards HIP, yet instead they make it sound somewhat breathless. The coding continues to be etude-like, stabilized by regular accenting (Audio examples 6a and 6b, performed by Schröder (1985) and Kuijken (1983)).

[3.18] I could comment on many other movements but it should suffice to say that although there are exceptions (like Schröder’s recording of the D minor Allemanda), both of their recordings easily fall back on the even and regular Classical-modernist style due to the mechanical accenting of beats; un-inflected, even bowing; and minimal variations in the timing of notes and groups of notes (cf. Examples 3 and 9). In other words, we can pinpoint molecular lines of supple segmentation that weaken and deterritorialize the modernist approach typical of non-specialist players like Milstein and Grumiaux. However, they do not become essential forces of disruption, lines of flight that may complete the process of deterritorialization. In neither recording are there persistent features that cause clear breaks and rupture the status quo for good. There is no becoming HIP. The new sound that could unequivocally be called HIP has not yet been territorialized. For this we have to turn to Sergiu Luca’s (1943–2010) recording from 1967–77.

[3.19] Luca’s version presents a radically new reading. In it we can observe one performing tradition colluding with another, giving new meaning to a familiar piece, enacting absolute deterritorialization. In effect, Luca’s assemblage actualizes the Idea through differenciated coding of its milieus, making it possible to encounter the Multiplicity’s dimensions in new ways; or rather, to hear hitherto unheard dimensions of the Idea.

[3.20] Of all the recordings of the Solos, Luca’s was the first to use a Baroque violin and bow. This assisted him in fostering a different imagination of the music (Luca 1974). Having a lower bridge, gut strings with looser tension, and a bow that is heavier at the frog (some of the key differences between a modern and a period instrument) enabled Luca to search for a different way of rendering the score. Additional parameters that helped him actualize this newly imagined Idea included information found in period sources on instrumental performance. In his version, the pure intensities of performance parameters start to segment and differenciate in new ways, creating an assemblage where the molar lines have coded articulation, rhythmic projection, tone, bowing, dynamics, phrasing, and ornamentation so as to territorialize a different layer of the multi-dimensional performance space.

Example 10. Diagram showing the relative strength of CMP (right side) and HIP (left side) features in Luca’s 1977 recording of the Solos, overlaid by the ratings for Kuijken’s two recordings for comparison

(click to enlarge and see the rest)

Audio Example 7. repeat of measures 1–8 Loure, Bach Partita in E major, Loure, performed by Luca

[3.21] What he achieved is visualized in Example 10. The comparison with Kuijken’s two recordings clearly shows Luca’s HIP style as opposed to the much more mixed territory of Kuijken’s readings. As can be seen from the subjectively rated performance dimensions, in Luca’s assemblage the phrasing points up short units that are articulated closely according to meter and pulse, and governed by harmony. Bowing is short, lifted, varied and inflected, allowing for differences in timbre and power between down and up-strokes, leading to myriads of dynamic shades, a constant chiaroscuro that further aids the perception of pulse and the liveliness of rhythm, and the hearing of small metric and melodic groups. Multiple stops tend to be slightly arpeggiated or lightly brought together in a bow-stroke. Although vibrato is used for highlighting certain notes, it is not the main means of tone production. Tone depends much more on bowing and because it is neither evened-out nor sustained, it creates varied timbres. Importantly—and uniquely until the later 1990s—Luca dares to embellish Bach’s score, not just with trills and short grace notes but also with melodic and rhythmic embellishments and variants. He does this especially in the Andante of the Sonata in A minor, the Loure of the Partita in E major (Audio example 7, performed by Luca (1967–77), and the Sarabande of the Partita in B minor, BWV 1002.

Example 11. The rhizome of performance style as observed in recordings of Bach’s solos made between 1977 and 2010 by violinists born between 1917 and 1985

(click to enlarge and see the rest)

[3.22] I will move on to discuss later recordings representing this new stylistic territory to show that here too, differences in degree are omnipresent, and the various assemblages that actualize the Idea of the Solos are prone to mix and match aspects of various performing traditions populating a continuum, a constantly shifting, transient style. As Example 11 illustrates, any point (element or dimension) can link up with any other, revealing the rhizome.(4) Even Luca’s recording has moments that blur the style (Example 10), allowing certain lines of the Classical-modernist style to thicken and re/deterritorialize: accenting in fast movements is at times (e.g. beyond the opening measures) similar to how a younger non-specialist violinist like Shlomo Mintz might deliver them. The reason why Luca’s recording still sounds more HIP even in such moments is because of his bowing, which remains lighter, shorter and much more inflected.

[3.23] To illustrate the information presented in Example 11—which is essentially the summary of which performance attributes were found in recordings made over the past 40 years—as well as Example 1 at the start, I will look in detail at three more cases: one where I study differences among violinists who specialize in HIP and use period instruments, another where I look at differences between subsequent recordings of two non-specialist violinists, and finally a rhizomic-idiosyncratic sample.

Differences within HIP

[3.24] To make my point about the infinite variability across performances even within ostensibly the same style, I turn to the Preludio of the Partita in E major because it is a seemingly straightforward moto perpetuo movement where interpretive choices might be limited. Finding micro- and macro- variations here would make a strong case for a constantly shifting performance practice.

[3.25] The movement is essentially a written out improvisatory figuration on broken chords. The even sixteenth notes imply a smooth virtuoso style and suggest a clockwork-like delivery of the continuous rhythmic motion, a.k.a. “moto perpetuo.” Bach chose the Italian title Preludio as opposed to the French Prélude, even though the rest of the Partita consists of French dances. This can create a dilemma for performers with an eye toward historical information. Although in general the term Prelude does not designate any particular form or genre—it is simply what one plays before playing anything else—the Italians tended to favor the motoric moto perpetuo style while the French were known for their freer, more flexible, improvised preluding style (Schröder 2007, 167–8; Ledbetter 2009, 165–7). Which one is appropriate in this case? Or rather, how much and through what coding and decoding of features can a performer push or pull the score to actualize one or the other type? Rather than thinking in categories of “virtuosic moto perpetuo” and “expressive improvisation,” it seems more meaningful to consider the emergent becomings (becoming-molar) as assemblages that actualize differenciated dimensions of the Multiplicity known as the E major Preludio.

[3.26] In discussing the Presto movement of the Sonata in G minor, Lester (1999, 108–22) shows in detail why harmony alone cannot help solve the interpretative questions of Bach’s perpetual-motion movements. Understanding Bach’s intricate patterns of rhythm—intricate in the sense that they belong to multiple levels of metrical hierarchy—is crucial for a vibrant and “un-étude”-like performance. Lester notes a remarkable characteristic of much of Bach’s music: that none of the competing “metric patterning seems strong enough to overwhelm the other” (111). This is true of the Preludio as well. The movement is a multiplicity, open to infinite variation because even when the performer makes particular choices regarding accentual patterns of a figuration, the listener may still hear the alternative (harmonic) option(s) as well (cf. Example 16). This characteristic of Bach’s music flies in the face of clockwork-like regularity, moto perpetuo or not. It opens up to the potential for toying with the music, exploring all its dimensions through differenciated accentual patterns that highlight the ambivalent harmonic meaning of chord sequences.

Example 12. Tempos of HIP Violinists in Bach E major Partita, Preludio

(click to enlarge)

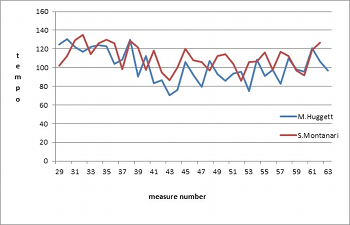

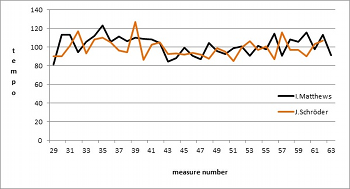

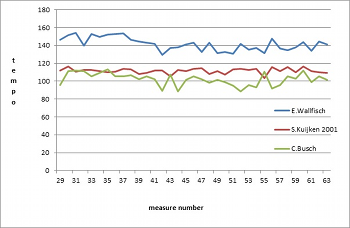

[3.27] So what do HIP specialists do in recorded versions of the E major Preludio? Of the fourteen versions I examined (listed in Example 12), all seem to project the underlying harmonic structure, some more clearly, others less obviously (for audio examples see below and at Examples 13–15). Local figurations are highlighted by agogic stresses, accents and inflections. These are less prominent in the faster versions that tend to emphasize the virtuosic element. The performances of Schröder, van Dael, Huggett and Montanari are the most detailed and uneven, especially Huggett’s which starts and stops the flow frequently. Compared to this uneven delivery and slower tempo, the versions of Schröder, van Dael and Huggett seem to sound labored, often pointing up measure-by-measure groups of notes, halting the forward momentum. Montanari avoids this effect because of his faster tempo and less frequent tempo fluctuations and timing stresses, even though these are significant in terms of magnitude. In his performance there are many regular sections and also excessively flexible ones. He often speeds up and slows down within measures (while keeping a generally consistent overall pulse) and introduces significant gaps between major sections, as before measure 29. Among the slower versions, smooth and less detailed performances are given by Kuijken (especially in 2001) and Beznosiuk. Luca, Holloway and Busch also play in a relaxed, fairly even style, but they create more detail through dynamics, articulation, and timing stresses; Luca’s faster tempo also assists flow and momentum. Like Busch, Holloway’s tempo and timing fluctuations are smoothly executed and over longer periods of time (unlike Huggett’s, for instance).

Audio Example 8a. Bach Partita in E major, Preludio, measures 29–63, performed by Wallfisch

Audio Example 8b. Bach Partita in E major, Preludio, measures 29–63, performed by Podger

[3.28] At the other end of the spectrum, where the “virtuoso moto perpetuo” territory emerges, Wallfisch performs very fast with sharp stabbing accents on downbeats, except during the bariolage sections and when the music moves in pairs of measures (Audio example 8a, performed by Wallfisch (1997)). Brooks is even faster, and apart from Ibragimova, the most virtuosic and even. Ibragimova’s slightly slower tempo allows her to highlight certain figurations (e.g. measures 39 and 58) and deliver the prescribed echo effects. In spite of their slower basic tempos, both Podger and Matthews also play in a virtuosic style, but they mark arrival points and the beginning of new figurations with timing stresses (agogics) or accents, for instance on each downbeat from measure 79 to measure 98. Matthews’ articulation shows more detail than Podger’s smoother playing, and she employs very noticeable tempo modifications as well, to build momentum and create contrast. These modifications are likely to have reduced her average tempo as calculated from overall duration. One clear example can be heard in the second bariolage section at measure 64, starting slowly and then speeding up. Other examples are when Matthews plays echo measures faster than the more independently articulated notes of the louder complementary measures. These tempo modifications immediately draw the listener’s attention. Matthews’ performance is different from Podger’s and represents another differenciated actualization of “the work” in between layers of fantasia and moto perpetuo. Like Huggett’s, Matthews’ intention seems to be to highlight many nuanced aspects of the Preludio, while Podger seems to engage with larger units. In Matthews’ performance, tempo and timing modifications are “propelled toward [the] rigid segmentarity” (Deleuze and Guattari 2012, 231) of a fantasia possibly deterritorialized by her hushed tone and slower tempo. In Podger’s performance, tempo and timing modifications “introduce a current of suppleness” (230) that weakens the rigid segmentarity of the moto perpetuo element, fostered by her smooth articulation and fast tempo (Audio example 8b, performed by Podger (1999)).

Example 13. Tempo flexibility in two “fantasia-like” performances of the E major Preludio, mm. 29–63

(click to enlarge and listen)

Example 14. Tempo flexibility in two “expressive” performances of the E major Preludio, mm. 29–63

(click to enlarge and listen)

Example 15. Tempo flexibility in three “literalist” performances of the E major Preludio, mm. 29–63

(click to enlarge and listen)

[3.29] To excavate the multiplicity of the Preludio (the Idea) a little further and to tease out the factors that play a part in differenciated actualizations, it is worth examining some of the recordings in more detail. Graphing tempo fluctuations shows the difference between the “expressive” and “clockwork-like” versions (Examples 13–15 with audio examples). The first three graphs show tempo variations during measures 29–63 (Example 16) in seven recorded performances. They demonstrate the major difference between approaches (coding and decoding milieus) that territorialize the “expressive” (Huggett, Montanari, Schröder, Matthews) and those that territorialize the “literalist” (Wallfisch, Kuijken, Busch) assemblages. They show the difference in the double articulation of content and expression. The lines in Examples 13–14 are constantly moving and the range of tempos covered is quite wide, especially in Example 13 (Huggett, Montanari). In contrast, the lines in Example 15 are much flatter and cover a smaller range (Wallfisch, Kuijken, Busch). The differences between Examples 13 and 14 underscore the transient and overlapping nature of emerging performance styles, the scope for differenciation within the multiplicity of “expressive,” including the emergence of another assemblage: “fantasia-like.” Close listening to these recordings reveals how timing, tempo, and dynamics are differenciated, exemplifying the case where “the molar and the molecular have very different combinations depending on the stratum considered” (Deleuze and Guattari 2012, 585). The coding and decoding of these performance features (the balance of their strength in terms of stylistic signification) reveal the different layers in the process of actualizing “expressive” and “literalist” interpretations. Sometimes performance features contribute to “expressive,” other times to “literalist” readings; they may tip an “expressive” towards the “fantasia-like” or the “literalist.” Take the role of tempo for instance. As we can hear in the audio examples, Matthews and Schröder play the section with echo measures (measures 43–55) in a steadier fashion than Huggett and Montanari, introducing literalist segmentarity into the “fantasia-like” (cf. the even flat lines in Example 14). The literal assemblages of Busch and Wallfisch are deterritorialized through the tempo arc between measure 44 and measure 52 (Busch) and the slight tempo fluctuation with every minor change in figuration and prescribed dynamics (Wallfisch speeds up in forte measures (measure 47) and slows down in piano measures (measure 48)).

Example 16. Bach Partita in E major, Preludio, mm. 29–63, with some annotations indicating various possibilities of accenting and grouping as observed in the recordings

(click to enlarge and see the rest)

[3.30] What is harder to see in the graphs is the coding and decoding of other parameters, such as the placement of dynamic and metrical accents and stresses (cf. Example 16). These are not always on the downbeat, but may highlight tonally or melodically important notes or alternative points in the figuration. The subtle micro-variations create assemblages between layers. A particular case in point occurs in measures 36–42. Here Schröder, for instance, emphasizes the downward pattern on the second beat of each measure, and through this differenciation propels the performance even more towards expressive segmentarity. In Busch’s performance, the molar segmentarity of a literalist reading is thickened through her continued stressing of downbeats until measure 39 (and also measure 40, but less so in measure 41). At this point, however, the articulation of the marked slurs creates emphasis on the second beat and introduces the suppleness of shifted accents. With the accented downbeat of measure 42 the literal stratum is reterritorialized. The differenciation of accenting in Montanari’s recording seems to involve both the downbeat and the second beat through various timing strategies and subtle dynamic nuances. He stresses the beginning of the downbeat and then hurries the rest of the notes, while he mildly accents and delays the second beat. But none of this is mechanical, so each time something slightly different happens—the coding and decoding is in constant flux, the fantasia-like assemblage transient and emergent.

[3.31] In describing these performances my aim is not at all to note differences among performances or between performance and score but to capture differenciations within the same (the Idea) and thus undermine the possibility of categorization. The analysis shows that the choice of basic tempo is not necessarily molar; both slower and faster versions could engender either the “flexible” or the “clockwork-like” delivery. Articulation and accenting are also both lines of rigid segmentarity and lines of supple segmentation as they interact to territorialize or deterritorialize emergent “literalist-moto perpetuo” and “expressive-fantasia-like” assemblages. The articulation of harmonic progressions and/or melodic figurations tends to be executed on a sliding scale from strongly to hardly perceptible, because the articulation of structures and figurations may be achieved through accenting, timing, bowing inflections, or a combination of these and other means. For instance, articulation through accenting stabilizes the “literalist” effect while articulation through timing or bow inflections tends to result in greater rhythmic flexibility, extracting the “expressive-fantasia” character. The differenciations in these technical elements create assemblages in-between layers. One aesthetic is weakened and another strengthened in the ongoing process of coding and decoding, resulting in transient assemblages shifting along layers of possibilities.

[3.32] All this shows the great variety in how violinists enact the “Idea” of the Preludio. The deceptive simplicity of the piece hides a richness of detail, a Multiplicity that even violinists ostensibly representing the same performing tradition (HIP) can interpret in diverse ways.

Personal artistic trajectory over time

[3.33] Throughout this article I have shown how the multiple, complex interactions of performance features are made visible. Example 11 visualized the results of aural analyses of some 30 recordings of the complete set of the Solos made during the past 40 years. The findings underscore their plurality and highlight their diversity. Categories dissolve and difference-from-self emerges. One final task remains, the study of multiple versions created by the same artist. How does the process of differenciation unfold in such actualizations of the multiplicity?

[3.34] For this task I turn to the subsequent recordings of Viktoria Mullova (b. 1959) and Christian Tetzlaff (b. 1966), and show that Mullova’s multiple recordings of the Solos are different while Tetzlaff’s are differenciated articulations of the same. The resultant assemblages reflect the violinists’ opposing trajectories of artistic aims and convictions.

[3.35] Victoria Mullova has three commercially available recordings of Bach’s Partita in B minor: the first from 1987, soon after she defected to the West from Moscow; then one on a disc of the three partitas from 1992–93 (reissued in 2006); and finally one on a complete set recorded in 2008–9. The first exemplifies the style she was taught at the Moscow Conservatoire. She remembers that she was required to make bow-changes imperceptible and play everything to be evenly beautiful. Performance of all music required a combination of “standardized beautiful sound, broad, uniform articulation, long phrasing, if possible, and continuous and regular vibrato on every single note” (2009, 1). This is exactly how the B minor Partita sounds on her 1987 recording: supremely sustained bowing, legato articulation, hardly any pulse, but lots of melody and arching dynamics. As she put it:

My Sonatas and Partitas became stiff, monotonous and even more difficult to perform [. . . ] I used to play them with very little articulation, and without the distinction between strong and weak beats that is so naturally linked to bow-strokes. But most of all, I didn’t understand the harmonic relationships, which are fundamental to a feeling of freedom and involvement in the musical argument (1).

[3.36] During the 1990s Mullova befriended musicians who specialized in historical performance practice, and through discussions, experimentation and performing together she has gradually revamped her approach to Baroque music (Mullova 2009; Mullova and Chapman 2012). The 1992–93 set still has a consistency of pulse and accenting that recall the “sewing-machine” style. Several movements are performed slower than in the 1987 recording and with a more detached bowing. These also contribute to the somewhat mechanistic effect and betray the Classical-modernist reading. At the same time she introduces embellishments in the Sarabande movement in this “middle” recording. Here the bowing has become lighter and more detached (especially in the first half), and the pulse is more perceptible. During repeats she also varies the rhythm, changing evenly written eighth notes to dotted pairs (measure 8). The added ornaments strengthen the pulse and make her play in a less sustained and more rhythmical way. But her bowing is still fairly long and uninflected (except perhaps when playing the chords) and she relies on arching dynamics for phrasing. In sum, this recording demonstrates the tension between the molar and the molecular—how “lines are constantly interfering, reacting upon each-other, introducing into each other either a current of suppleness or a point of rigidity” (Deleuze and Guattari 2012, 230). The 1992–93 recording might thus be called becoming-HIP.

Audio Example 9. Bach Partita in B minor, Sarabande, repeat of measures 9–17, performed by Mullova

Example 17. Stylistic characteristics in Viktoria Mullova’s 3 recordings of Bach Partita in B minor, BWV 1002

(click to enlarge and see the rest)

Example 18. Stylistic characteristics in Christian Tetzlaff’s two recordings of the Solos

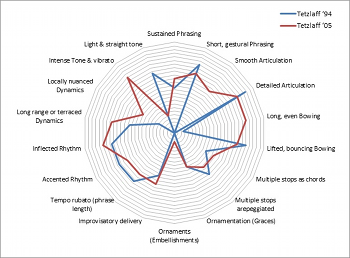

(click to enlarge and see the rest)

[3.37] By 2008 Mullova has internalized the precepts of HIP. Her bow-strokes are shorter, lifted and inflected, full of shade and light, strengthening the perception of meter while creating expression through the shifting nuances of dynamics. Her accenting is more varied (less reliant on simply marking downbeats) and so her phrasing becomes freer, shaping segments shorter here, longer there. The ornamentation suits the music even better than in the 1993 version; the timing of embellishments is exquisite, clarifying the meter and befittingly adorning both harmony and melody. There is nothing mechanical or regular about this performance, yet it sounds decidedly “Baroque” and not at all “Romantic”. To me it sounds beyond HIP (Audio example 9, performed by Mullova (1987, 1994, 2009)), grounded in mastery of the minutiae leading to a complete ownership of the style and thus the freedom to indulge in and to “commune with” the Idea, allowing it to emerge, to be actualized anew. The radar chart (Example 17) summarizes these observations and clearly shows the very mixed, in-between layers becoming of the 1993 album.

[3.38] Tetzlaff’s two recordings of Bach’s complete set of solo violin works show a different trajectory: similar to Mullova’s in the sense that it progresses towards greater individual conviction, but opposite in the sense that he seems to be moving away from the inspiration of HIP practices. In 1994, at the time of the first set’s release, Tetzlaff was known as a violinist influenced by HIP (Stowell 2001; Glass 1995). This can be heard when listening to that recording: the bowing is generally light and detached, vibrato is curtailed and used selectively, the articulation is fairly locally nuanced, rhythmic groups are inflected and closely articulated projecting a stronger pulse, chords are played lightly together, and so on (Example 18). But he plays with a modern instrument, so none of this sounds quite like it would with a period bow and Baroque violin. Still, when listening to his 2005 set we can notice differenciation in the actualization. The historically inclined literalist, carefully considered reading gives way to something much more expressive and personal. Vibrato is more frequently called upon, dynamics exploit extreme ranges, bowing and tone are often more intense or whispering soft and “disembodied”. We can hear longer phrases and the expression of heartfelt emotions. At the same time, there is increased virtuosity in the faster movements, like the Giga from the D minor Partita.

[3.39] The violinist himself provides some explanation for the change. Apparently he regards the six Solos to be “Bach’s personal prayer book” (Eichler 2012, 39). The implied introverted intimacy might be the key reason for the apparent increase in conventional expressive means such as tempo rubato and long-range crescendos and diminuendos.

Audio Example 10. Bach, Sonata in A minor, Fuga, measures 240–89, performed by Tetzlaff

[3.40] This greater and more personal expression can be observed even in the Fugue movements. In both recordings, Tetzlaff plays them flowingly with an easy forward momentum. But while in 1994 he tends to perform them with softer, consistent dynamics and marks very few cadence points to identify structural sections and aid the listener’s orientation to the form, in 2005 he shapes melodic, harmonic, or rhythmic units much more perceptibly. The many more local goals or arrival points and new starts are shaped through long-range dynamics and increasing and decreasing tonal intensity. To give just one specific example, in 1994, towards the end of the A minor Fuga, he abandons a crescendo that seems to be starting around measure 240. In contrast, in 2005 he creates several surges in dynamics (measures 240–51; 252 to 262 via measure 257), each building on the previous one. These are followed by a relaxation of tension (decrescendo between measures 269–80) before the final crescendo that leads to the ornament in measures 286–87 and the closing two bars (Audio Example 10, performed by Tetzlaff (1994, 2005)). Importantly for my concerns in this article, these more conventional expressive means and structuring are complemented with typical HIP articulation mechanisms, such as leaning on the first note of slurred pairs of eighth notes or slurred groups of sixteenths, and playing the other notes more lightly and rapidly. These deterritorialize the “Romantic-personal” sound and leave the listener to contemplate anew the endless dimensions of the Solos (the Idea).

4. The rhizome of performance

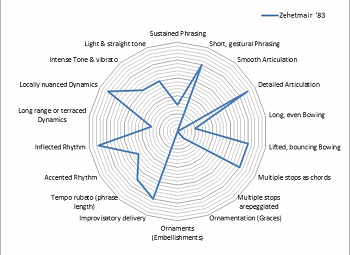

[4.1] Most of the analyses so far have demonstrated problems of classification, indicating constantly shifting, transforming, and emerging stylistic territories that mix and match various performance elements in diverse combinations and degrees. To underscore this finding, Thomas Zehetmair’s 1983 recording is worth a brief commentary. I argue that it is so idiosyncratic that it exemplifies more clearly than any of the others thus far discussed what Deleuze and Guattari call the rhizome: a heterogeneous system where any point can join to any other, where everything is brought into play in a non-organized, non-identifying, non-imitating way (Deleuze and Guattari 2012, 21, 233, 279).

[4.2] Zehetmair’s tempo choices often wildly diverge from the average tempos of some 60 recordings studied (Fabian 2005, 2015). His Standard Deviation scores are often greater than 2, and in the case of the A minor Andante it is 4.16. His vibrato is also quite unusual. Although it is not at all continuous but rather serves to highlight notes, it is often very slow and wide, way too noticeable. These are not the main issues, however. His individual style seems to come about from an interaction of explosive phrasing, creatively reckless bowing and accenting, abrupt changes in dynamics, and extreme short-range rubato. He plays ornamental groups of notes in a rapid, gliding fashion so that they do not sound like adornments, but more like erratic gestures. At the same time, his readings have an intensity and urgency that is gripping and expressive in an HIP manner. His bow-strokes tend to be lifted, his projecting of pulse strong, and his rhythm flexible, as it follows the accentual patterns of metric hierarchy. Together these create an articulation and dynamic nuancing not dissimilar to HIP versions.

Example 19. Stylistic characteristics in Thomas Zehetmair’s 1983 recording of the Solos

(click to enlarge and see the rest)

[4.3] Zehetmair’s reading might be labeled rhizomic because it is highly individual (Example 19). Although his bowing, articulation, and projection of rhythm seem to reflect the influence of HIP, he lifts these characteristics out of the HIP realm and infuses them with his own personal mannerisms. He is “cherry-picking” HIP features and construes their precepts unimpeded, coding-decoding-recoding ad lib. HIP dimensions like shorter, lifted bow-strokes, locally nuanced articulation, and vibrato-less tone mix freely with sustained bowing, intense vibrato, legato articulation, long phrases, tempo rubato and arching dynamics. What one would regard as the molar lines of HIP, or, for that matter, of the Romantic-modernist or Classical-modernist styles, get mixed up in such complex and rapidly interacting ways that something entirely free, unclassifiable and unidentifiable (rhizomic) is created, especially if one considers his set of the Bach violin solos as a whole.

5. Conclusions

[5.1] Perhaps not entirely surprisingly, the examination of recordings showed that hardly any of them fits perfectly the theorized categories RMP, CMP, and HIP (each of which Deleuze would call “the One”). Instead of representing distinct groups of styles, the performances occupy various overlapping positions in an imaginary space where the different dimensions of the composition are differenciated. Each performance enacts instances of diverse emergent assemblages actualizing the Multiplicity. Our understanding of style, performance, and performers is enriched by such a non-categorizing approach.

[5.2] I provided descriptions of various identifiable parameters and their interactions in order to unravel the limitations of categorical and hierarchical thinking. I showed that the contemplation of these descriptions—the thresholds of interpretative solutions, including technical details, expression, aesthetics and style—can usefully draw on Deleuzian terms, because they can assist the interpretation of the listening experience and analytical findings. Detailed descriptions of performance features and specific moments explore the becoming, the molar and molecular lines that thicken or thin the stylistic territory, that draw a context on the plane of immanence by extracting coded milieus. They help the interrogation of the processes of interactions, of transformation, of performing and its perception. The radar charts and drawn diagrams visualize these interactions and the resultant transience of performance style, especially if we imagine them spinning and rotating in a three- or n-dimensional space, enabling the scales to increase and decrease, reconfiguring their relative contributions, to become, as any particular moment in the emergent performance is differenciated. All this deepens our understanding of how performance elements interact in myriad non-linear ways, enabling performers to create ever-new actualizations of the Idea and the continuous evolving of performance style.

[5.3] In sum, I propose that monolithic musicological categories like HIP or modernist performance are the kind of “dogmatic, orthodox or moral” Image of thought that signals a thinking that “prejudges everything” (Deleuze 1994, 131). These constructs result from a belief that “thought has an affinity with the true; it formally possesses the true and materially wants the true” (131). I have tried to “take as [my] starting point of departure a radical critique of this Image and the ‘postulates’ [such musicology] implies” (132). At the end we are left with a paradox: we see the labels as inadequate yet emergent. A Deleuzian framework helps us understand them as becoming-molar rather than as arborescent (i.e. hierarchical and centralizing) and categorically a priori.

Dorottya Fabian

University of New South Wales Australia

School of the Arts and Media

Webster Building, 103

Sydney NSW 2052

d.fabian@unsw.edu.au

Works Cited

Anderson, Christopher, ed. 2006. Selected Writings of Max Reger. Routledge.

Butt, John. 2002. Playing with History. Cambridge University Press.

Campbell, Edward. 2013. Music after Deleuze. Bloomsbury Academic.

Cannam, Chris, Christian Landone, and Mark Sandler. 2010. “Sonic Visualiser: An Open-Source Application for Viewing, Analysing, and Annotating Music Audio Files.” Proceedings of the ACM Multimedia International Conference, October 25–29, Firenze, Italy. http://sonicvisualiser.org/

Cook, Nicholas. 2001. “Between Process and Product: Music and/as Performance.” Music Theory Online 7 (2).

—————. 2012. “Introduction: Refocusing Theory .” Music Theory Online 18 (1).

—————. 2014. Beyond the Score: Music as Performance. Oxford University Press.

Crawford, Tim and Lorna Gibson, ed. 2009. Modern Methods for Musicology. Ashgate.

Deleuze, Gilles. 1994. Difference and Repetition, translated by Paul Patton. Columbia University Press.

Deleuze, Gilles and Felix Guattari. 2012. A Thousand Plateaus, translated by Brian Massumi. Bloomsbury Academic.

Dreyfus, Laurence. 1983. “Early Music Defended against its Devotees: A Theory of Historical Performance in the Twentieth Century.” The Musical Quarterly 69 (3): 297–322.

Eichler, Jeremy. 2012. “String Theorist: Christian Tetzlaff Rethinks How a Violin Should Sound.” The New Yorker. 27 August: 34–39.

Fabian, Dorottya. 2003. Bach Performance Practice 1945–1975: A Comprehensive Review of Sound Recordings and Literature. Ashgate.

—————. 2005. “Towards a Performance History of Bach’s Sonatas and Partitas for Solo Violin: Preliminary Investigations.” In Essays in Honor of László Somfai: Studies in the Sources and the Interpretation of Music, edited by László Vikárius and Vera Lampert, 87–108. Scarecrow Press.

—————. 2015. A Musicology of Performance: Theory and Method Based on Bach’s Solos for Violin. Open Book Publishers.

Fabian, Dorottya, and Eitan Ornoy. 2009. “Identity in Violin Playing on Records: Interpretation Profiles in Recordings of Solo Bach by Early Twentieth-Century Violinists.” Performance Practice Review 14: 1–40.

Glass, Herbert. 1995. “A Reasoning Romantic—Profile: Christian Tetzlaff.” The Strad 106 (1259): 260–65.

Goehr, Lydia. 1992. The Imaginary Museum of Musical Works: An Essay in the Philosophy of Music. Clarendon Press.

Haynes, Bruce. 2007. The End of Early Music: A Period Performer’s History of Music. Oxford University Press.

Lawson, Colin and Robin Stowell. 1999. Historical Performance: An Introduction. Cambridge University Press.