“I got a bone to pick”: Formal Ambivalence and Double Consciousness in Kendrick Lamar’s “King Kunta”*

James Bungert

KEYWORDS: rap, hip hop, analysis, form, Kendrick Lamar, Signifyin’

ABSTRACT: Despite the profusion of rap analyses in the past decade or so, what is still missing is an explicit music-theoretical acknowledgement of the social message of the lyrics, of the essence of what most rap listeners immersed in the lyrics might glean from the music. This essay represents a call to engage rap music from an analytical standpoint that understands its inner workings from a music-theoretical perspective while also incorporating its social message into the analysis. This analysis of Kendrick Lamar’s “King Kunta,” from his landmark album To Pimp a Butterfly (2015), provides an illustrative case study. It first outlines an issue in the song’s formal structure, an ambivalence between a verse-chorus and a chorus-verse interpretation. It then contextualizes the song’s musical characteristics, including its flow, in terms of its West Coast influences, situates the song within the lyrical content of the album, and discusses in some detail Lamar’s use of “Signifyin(g),” an African American linguistic/literary practice. The essay concludes by considering the formal ambivalence and lyrical themes of “King Kunta,” along with Lamar’s position as a performer suspended between the rap game and American capitalism in light of DuBoisian “double consciousness” (1903). Incorporating rap’s social import into analyses not only bestows a social currency lacking in most other music theory scholarship, but more importantly it allows us to use music theory as a tool with which to understand current social issues.

DOI: 10.30535/mto.25.1.12

Copyright © 2019 Society for Music Theory

1. Introduction

[1.1] I got a bone to pick. Although the past decade has seen a refreshing and inspiring profusion of rap analyses, an explicit music-theoretical acknowledgement of the social message of the lyrics, the essence of what most rap listeners immersed in the lyrics might glean from their music, is largely missing. This essay represents a call to engage rap music from an analytical standpoint that both understands its inner workings from a music-theoretical perspective and acknowledges and incorporates its social message into the analysis.

[1.2] Rap analyses generally fall into two camps roughly corresponding to those outlined by Kyle Adams in the Cambridge Companion to Hip-hop (2015, 121–22): the work of Adam Krims and that of everybody else. Explicitly analytical works mentioned by Adams include those by Adams himself (2008, 2009), Justin A. Williams (2009), and Noriko Manabe (2006).(1) Additional work has appeared since 2015, including Mitchell Ohriner (2016), Nathaniel Condit-Schultz (2016), and others. Krims’s analyses, while technical at times, focus primarily on cultural context as related to the lyrics. Other studies focus generally on technical aspects of the music, which usually involve flow, the “rhythmical and articulative features of a rapper’s delivery of the lyrics.” (Adams 2009, 6); Ohriner (2016) and Condit-Schultz (2016), both appearing in a special issue of Empirical Musicology Review devoted to corpus studies, push in a more technical direction.

[1.3] The abovementioned analyses generally forego attention to lyrical meaning. Non-Krims analyses present sophisticated investigations of flow, but often to the exclusion of the lyrical meaning, sometimes explicitly.(2) Most, if not all, of the millions of self-described hip hop fans would likely include an accommodation of the lyrical content—the moral of the story—as among its most engaged modes of listening (in addition to appreciating flow, beats, etc.). Even Krims’s work, although entrenched deeply within the lyrics and providing thrilling in-depth musical analyses, seems to talk over the artists’ heads, in an abstruse academic language characteristic of cultural theory; in other words, Krims is so concerned with analyzing the cultural context of rap lyrics that their message at face value goes largely unacknowledged.

[1.4] This essay advocates an analytical approach to rap music that listens intently to the social message of the lyrics, and uses technical details of flow, form, etc., to illuminate that message. The present analytical forum, with its focus on Kendrick Lamar’s landmark To Pimp a Butterfly (2015), is a wonderful opportunity to explore a symbiotic relationship between structural and lyrical content in rap. The following analysis of “King Kunta” provides an illustrative case study. The essay first outlines an irreconcilable formal ambivalence in the song’s structure. Second, it contextualizes the song’s musical characteristics, including its flow, in terms of its influences from West Coast hip hop. Third, it situates the song within the lyrical content of the album as a whole and discusses in some detail Lamar’s use of the technique known as “Signifyin(g).”(3) My essay concludes by considering “King Kunta’s” formal ambivalence and lyrical themes, along with Lamar’s suspended position between the rap game and American capitalism in light of DuBoisian “double consciousness” (1965), what Imani Perry calls “the meeting and conflict of Americanness and blackness” (2004, 43).

2. Formal Ambivalence

Example 1. Basic formal organization of “King Kunta”

(click to enlarge)

Example 2. Rhythmic analysis of chorus (after Adams 2008 and 2009)

(click to enlarge)

Example 3. Formal ambivalence in “King Kunta”

(click to enlarge)

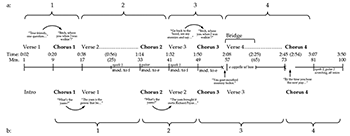

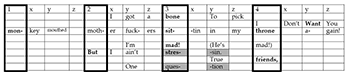

[2.1] From a formal standpoint, “King Kunta” presents an analytical challenge. Example 1 shows a basic formal layout while Example 2 presents a rhythmic analysis of the chorus (after Adams 2008 and 2009). The chorus alternates with verses throughout the song, and as we’ll see, its hierarchical status is ambiguous.(4) The diagram in Example 3a shows a verse-chorus interpretation.

[2.2] The song appears to begin directly with Verse 1, followed by the chorus, and the two sections alternate regularly through the remainder of the song, with Verse 2 (beginning in m. 17) and Verse 4 (beginning at m. 57) spanning sixteen measures each. Regardless of section length, the song comprises four large-scale sections with an Outro beginning in m. 81. This interpretation is reinforced by three salient musical events. First, a direct modulation occurs from E minor to F minor at the beginning of Verse 3 in m. 41, which suggests the beginning of a larger formal unit. (I will discuss the other modulations below.) Second, twice in the song the lyrics lead directly from the end of the verse into the chorus: from Verse 1 into Chorus 1 there is “True friends, one question. . . ” and from Verse 3 into Chorus 3 there is “go back to the ‘hood, see my enemies and say. . . ” both of which are answered by the chorus, a semantic connection reinforcing their concatenation into a larger formal group. Finally, a major musical break occurs at the end of Chorus 3 in m. 56: the beat stops completely and a deeper voice interjects “You goat mouthed mammy-fucker” before the bridge begins in m. 57. The eight measures of the bridge shed all instrumental layers except the bass ostinato, which, along with the interjection at the end of the chorus, produces a major textural break. This break both separates Chorus 3 (the end of the third large-scale group) from the bridge (the beginning of the fourth large-scale group) and could be interpreted as shifting the climax of the song from the chorus to the bridge.(5) Indeed, the bridge of “King Kunta” features the densest flow of the entire song, setting it even farther afield. As a bridge, we can understand it as part of Verse 4, or at least linking into the more proper verse-like section in m. 65, which in turn forms the fourth and final formal group with Chorus 4 in m. 73.

Example 4. Rhythmic analysis of introduction (after Adams 2008 and 2009)

(click to enlarge)

[2.3] Convincing though Example 3a’s verse-chorus interpretation may be, other musical evidence suggests a conflicting formal interpretation—a chorus-verse model—shown in Example 3b. Although there is sufficient evidence for a chorus-verse interpretation, it seems as though it must work against or resist what Brad Osborn calls the “verse-chorus paradigm” (2013, 23).(6) There are four significant differences in the two readings. First, the verse-chorus model from above reinterprets “Verse 1” as an Introduction. The table in Example 4 shows the flow of the first section, which features expansive, breathable phrase structure, sparse instrumentation, and thin rhyme scheme (only “stressin’” with “question” through eight full measures). Some verses feature this breathable phrase structure, but without prior formal knowledge, the song only seems to get going with the onset of the chorus. After the Introduction in m. 1 this chorus-verse interpretation continues in m. 9 with four large-scale chorus-verse sections that are directly out of phase with the verse-choruses of the first interpretation. Second, as mentioned above, the key returns to E minor in Chorus 3, suggesting the beginning of a larger formal unit. Interestingly, there was a previous modulation to F minor in Verse 1 (mm. 17–33) ignored by the other interpretation since it happened mid-verse, in m. 25, and thus didn’t support the verse-chorus model. This modulation also returns to E minor at the beginning of Chorus 2 in m. 33, thereby producing two tonal returns leading into successive choruses, reinforcing the beginning of the chorus as a large-scale formal division. Third, while the verse-chorus interpretation highlights the lyrics leading from verses into choruses twice, they also lead twice from choruses into verses: at the end of the first two choruses, Lamar raps “When you got the yams,” to which vocalist Whitney Alford responds with “What’s the yams?” The following verses answer the question about yams with “The yam is the power that be,” and “The yam brought it outta Richard Pryor.” As strongly as lyrics connect verses with choruses, then, “What’s the yams?” connects choruses to verses. Fourth, and perhaps most convincing, is the abrupt beat stoppage just before m. 73 at the end of Verse 3 and into Chorus 4. The beat stopped sixteen measures earlier, but here, after “Bitch, where you when I was walkin’,” the underlying pulse stops entirely, a fermata-like gesture in which the deep voice returns with “By the time you hear the next pop, the funk shall be within you” followed by the sound of a gunshot. Lamar continues the chorus a cappella “Now I run the game got the whole world talkin’,” which rekindles the full instrumental texture on the downbeat of m. 75 and resolves the metric tension of the fermata gesture. There is a break in the chorus before the Outro.

[2.4] Given the available evidence, “King Kunta” supports two conflicting formal interpretations that inhabit the same musical space. In order to reconcile the two interpretations, I will contextualize “King Kunta” stylistically in terms of earlier West Coast rap, examining its role within the lyrical themes of To Pimp a Butterfly as a whole, considering Lamar’s use of Signifyin(g) to express its social message. These characteristics represent both vital aspects of the song itself, and a major portion of what I feel engaged rap listeners (again, who are generally not music theorists) take away from this music, which facilitates a deeper understanding of “King Kunta’s” formal ambivalence, and of hip hop in general.

3. Genres and Flow

[3.1] Generally speaking, Lamar’s work resists categorization into any one hip hop genre (e.g., gangsta, conscious, trap, etc.). To Pimp a Butterfly, as a whole, incorporates various traditional African American musical styles: funk, soul, jazz, R&B, and spoken word poetry. Against this multifarious palette, “King Kunta” stands out as distinctly West Coast rap, a nod to his hometown of Compton, CA, and to its storied lineage of influential rappers. Its beat evokes “G funk,” a texture reminiscent of 70s funk with its explicit nod to the group “P Funk” (Parliament Funkadelic), a style exemplified by Dr. Dre’s 1992 album The Chronic: a pronounced bass ostinato with relatively sparse upper layers, leaving the mid-range open for greater perceptual focus on the vocals. Moreover, “King Kunta’s” beat is an allosonic quotation of Mausberg’s “Get Nekkid,” that is, an instrumental reproduction rather than a digital sample (autosonic quotation).”(7) Mausberg was a promising rapper, from Compton, like Lamar. Unlike Lamar, who generally avoided gang life (Goldbaum 2016), Mausberg was a member of the Bloods. He was shot dead in his home during a robbery in 2000, at age 21. In reproducing Mausberg’s beat in “King Kunta,” Lamar pays homage to another of his own formative influences while acknowledging a tragic aspect of gang life. The instrumental beat reinforces “King Kunta’s” connection to The Chronic, given the latter’s ubiquitous (and pioneering) use of jazz elements in a famously gangsta-rap album.(8) Additionally, Dre himself is an executive producer of To Pimp a Butterfly, and appears (with George Clinton) on the first track, “Wesley’s Theory.” As discussed in more detail below, these musical characteristics of “King Kunta” are critical in situating Lamar within the West Coast tradition, specifically that of Compton.

[3.2] The flow in “King Kunta” features what Krims (2000, 49–50) calls a sung style, which he suggests is incongruous with gangsta rap. Sung style is relatively simple, with syllables and rhythmic accents delivered primarily on the beat and its divisions, relatively strict couplet groupings, and rhymes occurring regularly on the same beat of each measure, whether beat 2, 3, or 4. The other songs on To Pimp a Butterfly employ more complicated, more perceptually difficult flow, so “King Kunta’s” sung style is all the more intriguing: whether or not Lamar intends it, it is possible that the simpler rhythms of sung flow facilitate a better focus on the formal ambivalence discussed above, to say nothing of the lyrical themes.(9)

4. Lyrical Themes, Signifyin’, and Yams

[4.1] Lyrically, “King Kunta” operates in light of the broad themes of To Pimp A Butterfly as a whole. The album addresses Lamar’s own real-life rise to fame with its inherent temptations, while confronting ubiquitous racial inequality. The temptation of exorbitant wealth appears initially in the opening track “Wesley’s Theory” as his “first girlfriend,” but soon transforms into a controlling female persona named “Lucy,” short for “Lucifer.” Later on, the South African panhandler in “How Much a Dollar Cost,” who we learn is God himself, is introduced in contrast to Lucy. In any case, the album’s overall message concerns love: love among African Americans, love for one another, and most importantly, love for oneself. With such potent themes in mind, the title “King Kunta” situates Lamar between two worlds. On one hand, he’s a “king” within the rap industry and in the eyes of those of his hometown of Compton, a reference imbued by a line from his verse in Big Sean’s “Control” (2013)—“I’m Makaveli’s offspring, I’m the king of New York / King of the Coast, one hand, I juggle ‘em both.”(10) On the other hand, he’s also a “slave” (by referencing “Kunta Kinte,” the main character of Alex Haley’s 1976 novel Roots: The Saga of an American Family) to the exploitative forces of the music industry and to the systemic racial prejudices of the American economy and judicial system. While the lyrics within the song do not develop the slave theme in significant detail, the titular reference to slavery, which is salient because of its repetition within the chorus, is compelling in terms of how Lamar couches it. As Natalie Graham points out, other rappers reference slavery, even the whipping scene in Roots specifically, but, in the toasting tradition of rap (in which MCs engage in over-the-top self-aggrandizement), only as the master wielding the whip.(11) She writes that “Lamar’s use of the figure of Kunta Kinte works differently. He risks the stain of slavery, by refusing to inhabit the body of the master. His appeal to the heroic figure of Kunta Kinte does not remain domesticated for mainstream consumption or conform to black respectability politics. . . . He presents the possibility that witnessing black people’s trauma should be traumatic, especially when histories of abuse are not universal or contained in a hermetically sealed past as in Roots” (Graham 2017, 126 and 127–28). Where other rappers aim to benefit from the image of Kunta Kinte, Lamar uses it seriously in imploring his listeners to embody the pain of slavery and to align his subservience to the capitalistic appetites of the music industry with one of the ugliest chapters of American history.

[4.2] Digging deeper into the lyrical content of “King Kunta,” Lamar’s abovementioned reference to “yams,” which is somewhat enigmatic, affiliates him with the African American linguistic practice called Signifyin(g),(12) which arose in the American South during slavery. Roger Abrahams writes that Signifyin(g) is a “technique of indirect argument or persuasion,” “a language of implication,” “to imply, goad, beg, boast, by indirect verbal or gestural means” (1970, 66–67; emphases original). Although Signifyin(g) can serve all of these ends, it is often used for negative purposes, to criticize someone or to cause them peril.(13) Although it is possible to understand Signifyin(g) in academic terms,(14) a pointed, practical discussion comes from Claudia Mitchell-Kernan, who speaks directly to an appropriate mode of listening:

The black concept of signifying incorporates essentially a folk notion that dictionary entries for words are not always sufficient for interpreting meanings or messages, or that meaning goes beyond such interpretations. Complimentary remarks may be delivered in a left-handed fashion. A particular utterance may be an insult in one context and not another. What pretends to be informative may intend to be persuasive. The hearer is thus constrained to attend to all potential meaning-carrying symbolic systems in speech events—the total universe of discourse. The context embeddedness of meaning is attested to by both our reliance on the given context and, most important, by our inclination to construct additional context from our background knowledge of the world. Facial expressions and tone of voice serve to orient us to one kind of interpretation rather than another. Situational context helps us to narrow meaning. Personal background knowledge about the speaker points us in different directions. Expectations based on role or status criteria enter into the sorting process. In fact, we seem to process all manner of information against a background of assumptions and expectations. (Mitchell-Kernan 1999, 311)

Imani Perry ties this idea directly to hip hop, writing that in rap, the sophistication of Signifyin(g) “far exceeds a simple reference or response—it is engagement with other texts and their traditions in the midst of one’s own piece, using the former as part of the ultimate creation of the latter” (2004, 63). As rap listeners, then, Signifyin(g) brings to bear the “total universe of discourse,” to listen not only within our own universe of possible meanings, but also beyond the linguistic content of the utterance itself to its other, less tangible aspects.(15)

[4.3] With all of this in mind, Lamar’s Signifyin(g) in “King Kunta” imparts, in Gates’s words, “a dreaded, if playful condition of ambiguity,” one worth teasing out in some detail. Indeed, for Perry, Signifyin(g) exists in all of what she calls the “multiple registers of hip hop”: “Access to these registers constitutes a test in familiarity with the artist and, for example, his or her sociopolitical or philosophical location” (2004, 61). Of Lamar’s many references, his reference to yams at the end of the first two choruses is perhaps the most potent. Taken literally, “yams” evoke edible tubers, sweet potatoes in the U.S., a component of Southern cuisine. But yams can also represent wealth and power, as exemplified, for instance, by Okonkwo, the rash protagonist in Chinua Achebe’s Things Fall Apart, who amassed several barns full of yams.(16) This indirect reference to African history alludes to the prehistory of rap. In Rap Music and Street Consciousness Cheryl Keyes traces the origins of rap back through Jamaica to African bardic traditions, e.g., the Kingdom of Mali (ca.1200–1500), in which an improvised song was recited rhythmically over an instrumental accompaniment. She writes that “most storyteller-singers are accompanied by a harp-lute (e.g., kora) or percussion instrument, whose repetitive beat interlocks with the bard’s voice.”(17) Directly in line with the ribbing nature of Signifyin(g), and with “King Kunta’s” titular reference to royalty, William D. Piersen writes that these African bardic griots sang history, royal praise (directly to the king), and particularly satire: “such satire was especially refined by the bardic griot[s] who were renowned for their praise songs but equally feared for the sharp, deflating barbs of their wit” (1999, 351). Whether Lamar intends these historical references or not, they align yams with a rich set of images through the multiplicative character of Signifyin(g).

[4.4] Calling yams “the power that be” at the beginning of Verse 2 (answering the chorus), Lamar piggybacks on their symbolic power in Africa, but in a slightly negative light. On one hand, “the power that be” is the power of “the man” that must be resisted. Most directly, he refers to Public Enemy’s 1989 song “Fight the Power,” whose chorus implores its listeners to “fight the powers that be!” This reference in turn alludes to both James Brown, whose “Funky Drummer” forms the beat for that song’s verse, and to the Isley Brothers’ 1975 song “Fight the Power.” Two lines later, the reference to James Brown becomes explicit with the line “I can dig rappin’,” which is a direct quote (in identical rhythm) from Brown’s song “The Payback” (1973). The yams also evoke temptations associated with power. At the start of Verse 3, Lamar raps “The yam brought it outta Richard Pryor, manipulated Bill Clinton with desires,” men from two vastly diverging demographics whose struggles illustrate the corrupting potential of power. Yams can also refer to balloons filled with drugs, particularly heroin or cocaine: Young Jeezy refers to yams in “And Then What, ft. Mannie Fresh”: “hide the rest of the yams at my auntie’s house.”

[4.5] Finally, and most strongly related to the king/slave bent of the song itself, the yams elicit an issue of cardinal importance in hip hop: authenticity. This reference is also apparently the deepest sense of Signifyin(g) in terms of Perry’s “multiple registers of hip hop.” She writes that

Sometimes the various registers conflict, so that the first level of text may actually affirm stereotypes of black men, for example, or appear to be misogynistic. Yet a deeper register of the text may then challenge the assumptions, describe feeling locked into the stereotype, reinterpret it to the advantage of the artist, or make fun of the holder of the stereotype. When registers conflict with each other, listeners find themselves in a quandary regarding the music’s interpretation. Should it be interpreted according to the deeper registers or the most superficial, more accessible ones? (Perry 2004, 61)

The line “You can smell it when I’m walkin’ down the street” is a well-known reference to a scene in Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man in which the narrator encounters a food truck selling Southern-style yams and experiences a sudden jolt of nostalgia. Originally from the South and becoming increasingly disillusioned in New York City, the sweet smell of yams imparts a feeling of authenticity missing since his youth. For Lamar, the yam Signifies two different registers (i.e., targets) of authenticity. The first includes rappers who, caught in the web of current hip hop production, lack originality. He raps: “I can dig rappin’, but a rapper with a ghost writer? / What the fuck happened? (Oh no!) / I swore I wouldn’t tell, / but most of y’all are sharin’ bars like you got the bottom bunk in a two-man cell (a two-man cell).” (“Bars” denote rap lyrics.) Lamar implies that inauthenticity is so rampant that he must inform the world—and as such, this instance of toasting other rappers exceeds the expected toast.(18)

Example 5. Power dynamic of Kendrick Lamar between Compton and the music industry

(click to enlarge)

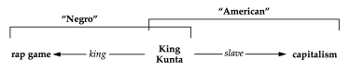

[4.6] The yam’s second, and much deeper, register of authenticity targets the music industry, Lamar’s former ‘hood in Compton, and, in paradoxical fashion, himself. Throughout “King Kunta,” Lamar peppers references to Compton; while they don’t verbally mention “yams,” these hometown references do engage yams in terms of their representations of power. In rapping about his ‘hood Lamar demonstrates a commitment to rap’s street heritage. He personifies what Murray Forman calls the “extreme local” (2002, xvii), which is one way for rappers to maintain authenticity throughout their rise to fame—that is, as they reach markets outside of and much larger than their hometown. In the words of Erik Nielson, the extreme local reflected “rap music’s increasingly urgent need to locate itself within familiar geographies just as it began to achieve national, and international, exposure” (2012, 355). Lamar’s references to Compton operate in light of the generally inimical purpose of Signifyin(g): with “Bitch where you when I was walkin’,” Lamar is calling out his former ‘hood for doubting him initially, but then praising him upon achieving fame.(19) Simultaneously, mentioning Compton constitutes Signifyin(g) against the music industry in that it incorporates content in which broader (national and international) consumers have no personal stake. It resists, in bell hooks’s words, “a consumer cannibalism that not only displaces the Other, but denies the significance of that Other’s history through a process of decontextualization” (2006, 373). In Signifyin(g) simultaneously against Compton and the music industry, Lamar effectively isolates and suspends himself between them—despite being both from Compton (shown clearly in the music video) and a major figure in the pop music industry. Example 5 represents this relationship visually. The “king” and “slave” arrows emanating from Lamar (in the middle position) show his complex king/slave relationship with Compton and the music industry. Likewise, the arrows returning to Lamar from the poles complete those implicit relationships. The “yams” arrows through the middle throw off the diagram’s implicit symmetry by showing the one-directedness of power, Lamar’s over Compton and the music industry’s over Lamar. In situating himself in the mid ranks of Example 5’s power structure, Lamar suggests the danger of becoming the very powers against which his image of yams Signifies.

Example 6. Beat of “King Kunta”

(click to enlarge)

[4.7] In light of his suspension between Compton and the music industry, Lamar's implicit reference to “Fight the Power” illuminates a deeper relationship between “King Kunta’s” lyrics and its beat. Considering the song’s explicitly African themes, “King Kunta’s” beat and flow are heavily duple, with a conspicuous lack of two-against-three polyrhythms, characteristically African and African-diasporic rhythms. Example 6 notates the basic beat.(20) As is apparent, it is almost entirely quarter- and eighth-note driven, with few sixteenth-note rhythms until the background synthesizer riffs beginning in m. 41. The snare forms a straightforward backbeat, and the kick drum pushes steady quarter notes, with eighth notes propelling from the and-of-two into beat three of each measure. The most noteworthy aspect of the beat is the faint eighth-note washboard pattern which replaces the traditional hi hat; despite the absence of polyrhythms reminiscent of African rhythms, the washboard explicitly references both the jug band tradition of the South, with its ties to jazz, blues, and early rock and roll, and the African practice of “hamboning,” in which musicians dance and play rhythms on their own bodies.(21) The flow is sixteenth-note driven, as discussed, and there are no triplets anywhere in the song—no hemiolas at higher metrical levels except “Annie are you OK, Annie are you OK,” a quote of Michael Jackson’s “Smooth Criminal.” Consequently, Lamar’s implicit reference to Public Enemy’s “Fight the Power” becomes all the more interesting. Robert Walser (1995) discusses in detail the relationships between Chuck D.’s lyrics, his rhythmic delivery, the song’s message of organizing struggle against oppression, and the rhythmic intricacies of the beat. He understands Chuck D.’s relatively capricious polyrhythmic delivery in terms of African-diasporic music. Connected with this understanding of the beat, “King Kunta’s” lack of polyrhythms enhances the sense of Lamar’s dissociation from Compton and the music industry. On one hand, it extends past Compton all the way to his African and African American musical roots. On the other hand, pace Public Enemy as a prominent representative of hip hop’s Golden Age, it expresses his own position within hip hop’s post-commercial status, its conspicuous lack of, in Walser’s words, “adaptability and tolerance in the face of a potentially disorienting and alienating world” (1995, 209).

5. Conclusion: Power Dynamics, Double Consciousness, and Chitterlings

[5.1] Being caught between running the rap game as a young African American and being exploited by powerful economic forces evokes a centuries-old African American struggle and ultimately provides a lens through which to interpret the formal ambivalence discussed above.(22) Imani Perry writes that “the particular performative space of rap is located at the crossroads of several significant moments. Here one stands at the new grounds of DuBoisian double consciousness, the meeting and conflict of Americanness and blackness, where MCs and DJs are commodified, make commodities, and are both objects and subjects of capitalism as they produce improvisational and oppositional music” (2004, 43). Du Bois’s own description of double consciousness from The Souls of Black Folk (1903) is disquietingly apropos to Lamar’s ensnarement within the symbiotic interplay between the rap game and capitalism:

After the Egyptian and Indian, the Greek and Roman, the Teuton and Mongolian, the Negro is a sort of seventh son, born with a veil, and gifted with second-sight in this American world,—a world which yields him no true self-consciousness, but only lets him see himself through the revelation of the other world. It is a peculiar sensation, this double-consciousness, this sense of always looking at one’s self through the eyes of others, of measuring one’s soul by the tape of a world that looks on in amused contempt and pity. One ever feels his twoness,—an American, a Negro; two souls, two thoughts, two unreconciled strivings; two warring ideals in one dark body, whose dogged strength alone keeps it from being torn asunder. (DuBois [1903] 1965, 214–15)

This “meeting and conflict of Americanness and blackness,” these “two souls, two thoughts, two unreconciled strivings” reflect Lamar’s seclusion between the rap game and capitalism. Example 7 clarifies this relationship. Here, the connection operates slightly differently than the power dynamic sketched in Example 5: we can begin to understand the formal ambivalence of “King Kunta” in terms of double consciousness. On one hand, King Kunta (Lamar) “strives” as a rapper to achieve and maintain a position as a “king” within the rap game, a striving from which his “Negro” identity ostensibly arises. On the other hand, he “strives” as an “American,” but as a black man facing social, racial, and economic obstacles, he remains a “slave.” These two “warring ideals,” rapping and participating successfully in mainstream American society, are mutually opposing, and within the current context, can never unite.(23)

Example 7. Double consciousness power dynamic of “King Kunta” between the rap game and capitalism (after DuBois 1965)

(click to enlarge)

[5.2] Explicating Lamar’s unique position between the rap game and capitalism, Example 7 sheds new light on the formal conundrum outlined in detail near the beginning of the essay. Recall that there is musical evidence for a formal interpretation that groups the sections of “King Kunta” into verse-choruses, but also evidence that groups them into chorus-verses, two mutually opposing interpretations that cannot be reconciled as such. In a sense, this formal ambivalence gives rise to a kind of analytical “double consciousness,” “two thoughts, two unreconciled strivings,” even “two warring ideals” within one song. Where some analysts might be tempted to choose one interpretation over the other based on any of “King Kunta’s” musical, technical, or lyrical characteristics, I see the suspension between formal interpretations in terms of Lamar’s suspension within power dynamics—as the core content of the song, an understanding, an analytical solution, as it were, accessible through incorporation of the song’s lyrics.

[5.3] Inasmuch as Lamar is rapping about himself and about the struggles of African Americans, “King Kunta” also represents a statement about present-day America: just as African Americans experience double consciousness, finding themselves torn between the “Negro” and “American” worlds, America itself holds African Americans, especially celebrities like rappers and professional athletes, to a double standard. In this sense, hip hop, as it is consumed in the United States, is often characterized as a kind of modern-day minstrelsy. One factor is that record executives, who have gained unprecedented control of airplay with the consolidation of music markets in the past twenty-five years (Rose 2008, 17ff.), have pushed hip hop away from its earlier political orientation toward what Tricia Rose calls the “commercial trinity of hip hop”—the black gangsta, pimp, and ho (2008, 4)—and in facilitating studio production, have also undoubtedly sterilized much of its authenticity. Jeffery O. G. Ogbar writes that the “unthinking, uncivilized neominstrel. . . has, in fact, handily dominated rap representations of black males to such an extreme that between Dr. Dre’s gangsta standard The Chronic (1992) and 2006 only two adult solo black male rappers (Wyclef Jean [Carnival, 1997] and Will Smith [Big Willie Style, 1997]) have gone platinum without killing ‘niggas,’ referencing bitches, hos, and nihilistic violence on an album” (2007, 29).(24) Another factor is that while African Americans only represent approximately thirteen percent of the United States population (as of 2010), the hip hop consumption gap between whites and blacks between 2002 and 2006 averaged 34.4%, with white consumers averaging 61.6% of the hip hop market and blacks averaging 27.2% (Rose 2008, 88).(25) These factors suggest that, speaking economically through its spending habits, America expects black artists to rap about inner-city life (reality or otherwise) through artistic personas threatening to become indistinguishable from their actual personality. The double standard then arises when these same artists are then criticized for the very personas cultivated by market demand. In other words, hip hop consumers (consciously or not) are paying to see the portrayal of a degradation of a people. This lucrative portrayal, which rapper Heavy D calls “black death,” evokes Nelson George’s comparison of gangsta rap, featuring young black men killing one another on the street, to the battle royal, a deplorable Jim Crow era spectacle in which approximately ten young black males would brawl blindfolded for a white audience in a boxing ring (the first event of an evening of boxing matches); the last person standing received a trifling prize not nearly compensating for their likely injuries, and the beaten men received nothing (George 1998, vii).(26) The media, as expected, both simplifies and inflames this infinitely dynamic and complicated situation. Imani Perry wries that “generally speaking, the mainstream press categorizes and creates dichotomies of good and bad. It does not foster debate when it comes to hip hop, but rather encourages the censorship of ideological diversity through condemnation or praise. Mainstream media efforts at morality often appear more disingenuous and controlling than conscientious” (2004, 6). In other words, the media, far from consistently reporting anything approaching the complexity of truth, reinforces the racial dynamics of double consciousness.

[5.4] In conclusion I would like to revisit the disciplinary issue that framed this essay from the outset. While the growing field of rap analysis is necessary and exciting, it has not yet incorporated the social message of the lyrics in a substantial way into the theoretical discussions. The foregoing analysis, and to some extent this entire symposium is an example that intends to do just that: understand “King Kunta” in terms of its formal ambivalence (verse-chorus vs. chorus-verse) and its lyrical content (its prismatic Signification, its position within the album, commentary on contemporary America, etc.) in order to demonstrate an analytical symbiosis between technical and lyrical study in rap. And indeed, although this essay has focused on formal peculiarities and aspects of Lamar’s Signifyin’, music analysis that addresses this disciplinary issue could take any number of forms, focusing on the myriad aspects of rap music. In any case, addressing these disciplinary issues would join music theory subfields only recently turning their attention to current social issues through work in gender studies, disability studies, music and protest, etc. As of October 2016, the Society for Music Theory has “continued demographic imbalances,” with 87.1% of its membership identifying as white (Fankhauser 2016). Although the formal ambivalence of “King Kunta” is abstractly and technically irreconcilable, it is my hope that this attempt to synthesize the two sides of the rap-analysis coin, “Krims” and “other,” also be taken as work toward reconciling the two sides of DuBoisian double consciousness, which is inextricably bound up with weighty concerns such as systemic racism, the war on drugs, white privilege, police brutality, prison reform, and so forth. Incorporating rap’s social import into analyses not only bestows a social currency lacking in most other music-theoretical work but, more importantly, it allows us to use music theory as a tool with which to understand current social issues.

[5.5] Finally, attending to the lyrics in analysis allows hip hop scholars a chance for a kind of double acknowledgement. An idea by Tricia Rose has stuck with me while penning this essay: “Remember what is amazing about chitterlings and what is not” (2008, 264–67). Chitterlings are a soul-food delicacy involving boiling, breading, and frying what is perhaps the least desirable part of a pig: intestines. They originated during slavery, when masters kept the best cuts of pork for themselves and gave the rest to the slaves, no doubt feeding them as cheaply as possible. Rose implores her readers to both enjoy what is delicious about chitterlings while also acknowledging the humanitarian crimes that gave rise to them. Historically, the rise of hip hop mirrors that of chitterlings: slum conditions in the South Bronx in the early 1970s, motivated by the very same social and economic forces addressed in “King Kunta,” which were literally set into motion during slavery, provided the raw materials out of which creative individuals forged our beloved art form. This is to say that as we celebrate all of hip hop’s aesthetic qualities, as we devote to it the serious scholarly attention it deserves, we must also acknowledge the dehumanizing conditions that gave rise to it. It stands to reason, then, that we, a community with the distinct privilege of making listening a significant portion of our livelihood, strive to listen as comprehensively as possible. As I hope to have demonstrated with my analysis of “King Kunta,” incorporating the social message of the lyrics into our analyses is one way to celebrate its musical qualities while understanding its function in the world.

James Bungert

Rocky Mountain College

1511 Poly Drive

Billings, MT 59105

jim.bungert@rocky.edu

Works Cited

Abrahams, Roger. 1970. Deep Down in the Jungle: Negro Narrative Folklore from the Streets of Philadelphia. Adeline Publishing.

Achebe, Chinua. 1958. Things Fall Apart. Heinemann.

Adams, Kyle. 2008. “Aspects of the Music/Text Relationship in Rap.” Music Theory Online 14 (2).

—————. 2009. “On the Metrical Techniques of Flow in Rap Music.” Music Theory Online 15 (5).

—————. 2015. “The Musical Analysis of Hip-Hop.” In The Cambridge Companion to Hip-Hop, ed. Justin A. Williams, 118–34. Cambridge University Press.

Alim, H. Samy. 2006. Roc the Mic Right: the Language of Hip Hop Culture. Routledge.

Boone, Christine. 2013. “Mashing: Toward a Typology of Recycled Music.” Music Theory Online 19 (3).

Brackett, David. 1992. “James Brown’s ‘Superbad’ and the Double-Voiced Utterance.” Popular Music 11 (3): 309–24.

Condit-Schultz, Nathaniel. 2016. “MCFlow: A Digital Corpus of Rap Transcriptions.” Empirical Musicology Review 11 (2).

DuBois, William Edward Burghardt. [1903] 1965. “The Souls of Black Folk.” In Three Negro Classics, 207–390. Avon Books. Originally published in 1903 as The Souls of Black Folk. A.C. McClurg & Co.

Edwards, Paul. 2009. How to Rap: the Art and Science of the Hip-Hop MC. Chicago Review Press.

—————. 2013. How to Rap 2: Advanced Flow and Delivery Techniques. Chicago Review Press.

Ellison, Ralph. 1995. Invisible Man. 2nd edition. Vintage International.

Ewell, Philip. 2013. “‘Sing Vasya, Sing!’: Vasya Oblomov’s Rap Trios as Political Satire in Putin’s Russia.” Music & Politics 7 (2).

Fankhauser, Gabriel. 2016. “Demographics Report.” Society for Music Theory. Accessed December 18, 2017. https://societymusictheory.org/files/SMT Demographics Report Oct 2016.pdf.

Forman, Murray. 2002. The ‘Hood Comes First: Race, Space, and Place in Rap and Hip-hop. Wesleyan University Press.

Gates, Jr., Henry Louis. 1988. The Signifying Monkey: A Theory of Afro-American Literary Criticism. Oxford University Press.

George, Nelson. 1998. Hip Hop America. Penguin Books.

Goldbaum, Zach. 2016. Bompton with Kendrick Lamar. Video, 10:57. https://www.viceland.com/en_us/video/bompton-with-kendrick-lamar/56ba3d2707bdbcd113640fb4.

Graham, Natalie. 2017. “What Slaves We Are: Narrative, Trauma, and Power in Kendrick Lamar’s Roots.” Transition 122 (1): 123–32.

Greenwald, Jeff. 2002. “Hip-Hop Drumming: The Rhyme May Define, but the Groove Makes You Move.” Black Music Research Journal 22 (2): 259–71.

Hale, Andreas. 2017. “‘To Pimp a Butterfly’: Lamar shares history.” Accessed December 20, 2018. https://www.grammy.com/grammys/news/pimp-butterfly-kendrick-lamar-shares-history.

Haley, Alex. 1976. Roots: The Saga of an American Family. Doubleday.

Hayasaki, Erika. June 4, 2002. “Some Principals Ban Dance With Gang Ties.” Los Angeles Times.

hooks, bell. 2006. “Eating the Other: Desire and Resistance.” In Media and Cultural Studies: KeyWords, ed. Meenakshi Gigi Durham and Douglas M. Kellner, 366–80. Wiley.

Katz, Mark. 2010. Capturing Sound: How Technology Has Changed Music. University of California Press.

Keyes, Cheryl. 2002. Rap Music and Street Consciousness. University of Illinois Press.

Krims, Adam. 2000. Rap Music and the Poetics of Identity. Cambridge University Press.

Lacasse, Serge. 2000. “Intertextuality and Hypertextuality in Recorded Popular Music.” In The Musical Work: Reality or Invention? ed. Michael Talbot, 35–58. Liverpool University Press.

Manabe, Noriko. 2015. The Revolution Will Not Be Televised: Protest Music After Fukushima. Oxford University Press.

—————. 2006. “Globalization and Japanese Creativity: Adaptations of Japanese Language to Rap.” Ethnomusicology 50 (1): 1–36.

Mitchell-Kernan, Claudia. 1999. “Signifying, Loud-Talking and Marking.” In Signifyin(g), Sanctifyin’, & Slam Dunking: A Reader in African American Expressive Culture, ed. Gena Dagel Caponi, 309–30. University of Massachusetts Press. Originally published in 1972 Rappin’ and Stylin’ Out: Communication in Urban Black America, ed. Thomas Kochman, 315–35. University of Illinois Press.

Miyakawa, Felicia. 2005. Five Percenter Rap: God Hop’s Music, Message, and Muslim Mission. Indiana University Press.

Nielson, Erik. 2012. “‘Here Come the Cops’: Policing the Resistance in Rap Music.” International Journal of Cultural Studies. 15 (4): 349–63.

Ogbar, Jeffery O. G. 2007. Hip-Hop Revolution: The Culture and Politics of Rap. University Press of Kansas.

Ohriner, Mitch. 2016. “Metric Ambiguity and Flow in Rap Music: A Corpus-Assisted Study of Outkast’s ‘Mainstream’ (1996).” Empirical Musicology Review 11 (2).

—————. Forthcoming. Flow: Expressive Rhythm of the Rapping Voice. Oxford University Press.

Osborn, Brad. 2013. “Subverting the Verse-Chorus Paradigm: Terminally Climactic Forms in Recent Rap Music.” Music Theory Spectrum 35 (1): 23–47.

Perry, Imani. 2004. Prophets of the Hood: Politics and Poetics in Hip Hop. Duke University Press.

Piersen, William D. 1999. “A Resistance too Civilized to Notice.” In Signifyin(g), Sanctifyin’, & Slam Dunking: A Reader in African American Expressive Culture, ed. Gena Dagel Caponi, 348–70. University of Massachusetts Press. Originally published in 1993 in his Black Legacy: America’s Hidden Heritage. University of Massachusetts Press.

Rose, Tricia. 2008. The Hip Hop Wars: What We Talk About When We Talk About Hip Hop—and Why it Matters. BasicCivitas Books.

Schloss, Joseph G. 2004. Making Beats: The Art of Sample-Based Hip-Hop. Wesleyan University Press.

Schweig, Meredith. 2014. “Hoklo Hip-Hop: Re-signifying Rap as Local Narrative Tradition in Taiwan.” CHINOPERL: Journal of Chinese Oral and Performing Literature 33 (1): 37-59.

—————. 2016. “‘Young Soldiers, One Day We Will Change Taiwan’: Masculinity Politics in the Taiwan Rap Scene.” Ethnomusicology 60 (3): 383-410.

Sewell, Amanda. 2013. “A Typology of Sampling in Hip-Hop.” Ph.D. Dissertation. Indiana University.

Spicer, Mark. 2004. “(Ac)cumulative Form in Pop-Rock Music.” Twentieth Century Music 1 (1): 29–64.

Walser, Robert. 1995. “Rhythm, Rhyme, and Rhetoric in the Music of Public Enemy.” Ethnomusicology 39 (2): 193–217.

Williams, Justin A. 2009. “Beats and Flows: A Response to Kyle Adams.” Music Theory Online 15 (2).

—————. 2013. Rhymin’ and Stealin’: Musical Borrowing in Hip-Hop. University of Michigan Press.

Footnotes

* Thanks are in order to Philip Ewell and to the other members of this symposium. In particular, I would like to thank Anthony Hammond for introducing me to the music of Kendrick Lamar, and consequently, to the world of hip hop.

Return to text

1. Works that, according to Adams, are “broadly speaking, analytical” (2015, 122–23) but not explicitly music-theoretical include Robert Walser (1995), Jeff Greenwald (2002), Joseph Schloss (2004), Felicia Miyakawa (2005), Mark Katz (2010), Amanda Sewell (2013), Christine Boone (2013), and Williams (2013). Recent works not mentioned by Adams, but which could be called analytical, are Philip Ewell (2013), Noriko Manabe (2015), and Meredith Schweig (2014 and 2016). The work of Paul Edwards is worth mentioning here; although it is not music theoretical nor explicitly analytical, it does outline compositional and performance aspects of hip hop through artist interviews (2009) and involves considerably detailed discussions of rhythm and flow (2013).

Return to text

2. Ohriner’s essay in this symposium, in which he relates text-to-beat alignment to the meaning of the lyrics explicitly and in considerable depth, is a strong counterexample. Manabe 2006, Adams 2009, and Ohriner’s forthcoming monograph are also exceptions in that their technical analyses briefly incorporate aspects of the text’s meaning. However, lyrical meaning, for them, is generally subordinate to technical analyses.

Return to text

3. Signifyin(g) is a linguistic practice comprising indirect reference or persuasion, often negative, that arose in the American South during slavery.

Return to text

4. The chorus functions as such primarily because it appears four times with an internal repetition of the lyrics (see Example 2) and it includes the song’s name. However, it is not clearly nor consistently distinguished from the verses. It lacks a hook in that its lyrical delivery matches that of the verses, and it is not set into relief by any textural changes. In fact, the song gradually accrues instrumental layers (synth 1, guitar, etc.). This creates a parallel formal characteristic that evokes what Mark Spicer called an accumulative form, which involves a phenomenological component inviting the listener “into the formal process as it unfolds in real time” (2004, 61). Indeed, the accumulative aspects of the form, parallel though they are with the alternation between chorus-like and verse-like sections, tend to obscure larger section groupings. In any case, the remainder of the essay will refer to this section as the “chorus” owing primarily to its various forms of repetition.

Return to text

5. One could then argue that this shift upsets the rhetorical function of the verse-chorus paradigm, which is traditionally the case with the focus being on the chorus. To my knowledge, there is no literature exploring this formal peculiarity.

Return to text

6. It could be argued that the “verse-chorus paradigm” is more applicable to pop/rock than to hip hop, given hip hop’s underground origins. Moreover, recent hip hop songs often begin with the chorus. See, for example, DJ Khaled’s “No Brainer,” French Montana’s “Unforgettable,” Lil Peep’s “Save That Shit,” and Lil Uzi Vert’s “New Patek.”

Return to text

7. For more on the distinction between allosonic and autosonic quotations, see Lacasse 2000 and Williams 2013. In any case, “Get Nekkid,” also in E minor, has truckdriver modulations as well, but down a semitone rather than up. They occur during the last four measures of Verses 1 and 3, before modulating back up to E for the chorus. In contrast to “King Kunta’s” formal ambivalence, “Get Nekkid” features a clear verse-chorus form, with an eight-measure introduction, three large verse-chorus sections (each with sixteen-measure verses and eight-measure choruses), an eight-measure bridge without rapping, a final statement of the chorus, and an eight-measure outro.

Return to text

8. Farther yet, in an interview with www.grammy.com, producer Mark Spears, aka “Sounwave,” said that “When we first did ‘King Kunta,’ the beat was the jazziest thing ever with pretty flutes. Kendrick said he liked it but to ‘make it nasty’” (Hale 2017). One wonders if Sounwave originally had in mind the prominent flute solo from “Lil Ghetto Boy,” the seventh track on The Chronic.

Return to text

9. One could argue that sung style is consistent with the release of “King Kunta” as the album’s third single — to facilitate listening in radio play. However, the first two singles, “i” and “The Blacker the Berry,” both feature more difficult flows. The flow of “i” is rhythmically sung, but Lamar’s voice is in a higher register and many of the consonants are not enunciated as they are in “King Kunta,” so the lyrics are more difficult to understand; on the other hand its chorus (“I love myself!”) clearly functions as a chorus. The flow of “The Blacker the Berry” is primarily spoken, rhythmically highly sophisticated, and delivered in a gritty, raspy voice.

Return to text

10. As “Makaveli’s offspring,” Lamar references his West Coast pedigree as a descendent of Tupac Shakur, who often referred to himself as “Makaveli.” But as the “King of New York / King of the [West] Coast, one hand, I juggle ‘em both,” Lamar claims to rule over both East and West, the entire rap game.

Return to text

11. For example, Ice Cube, in “No Vaseline,” toasts MC Ren, a former co-member of N.W.A., by rapping “cause he’s going out like Kunta Kinte/But I got a whip for ya, Toby” (Graham 2017, 128).

Return to text

12. Following Gates 1988, this essay will capitalize the “S” and parenthesize the “g” in “Signifyin(g)” in order to differentiate it from the standard English word “signifying.”

Return to text

13. In this vein, H. Samy Alim equates Signifyin(g) with “Black terms, bustin, crackin, and dissin” (2006, 81). Signifyin(g) is most directly associated in the United States with the “Signifyin’ Monkey,” a mythical trickster who has roots in a divine trickster from Yoruba mythology named Esu-Elegbara (Gates 1988, 5). The locus classicus Signifyin’ Monkey story involves the monkey convincing the lion (who had physically abused the monkey in the past) that the elephant has been bad-mouthing him behind his back, and that he should seek revenge. Angered, the lion confronts the elephant, but is severely beaten by the (much larger) elephant—the result the monkey had in mind from the beginning, as revenge for the lion’s abuse. A similar and perhaps more familiar character is “Br’er Rabbit” from Joel Chandler Harris’s Uncle Remus stories.

Return to text

14. Henry Louis Gates Jr.’s book The Signifying Monkey: A Theory of African-American Literature (1988), in which Gates presents a theory of Signifyin(g) based on intertextual relationships in African American literature, undoubtedly leads the academic discussion, both historically and intellectually. For Gates, Signifyin(g) involves no less than “a protracted argument over the nature of the sign itself, with the black vernacular discourse proffering its critique of the sign as the difference that blackness makes within the larger political culture and its historical unconscious” (45). A kind of master trope in African American literature, Signifyin(g) indicates for a standard English term an indeterminate number of possible meanings, such that the act of Signifyin(g) itself can be said to Signify on the very meaning of meaning.

Return to text

15. Krims (2000, 95 and 112) discusses Signifyin(g), but rather than using it to peel back layers of meaning of particular rap lyrics, he references it in its capacity in identity formation for African American artists.

Return to text

16. “Yam, the king of crops, was a man’s crop” (Achebe 1958, 23).

Return to text

17. “A bard may also be accompanied by an apprentice, the naamu-sayer, who responds by saying ‘naamu’ in affirmation of the bard’s words, adding an active interchange between the bard and the naamu-sayer, who represents the voice of the listener” (Keyes 2002, 20). Here we not only see a verbal art form difficult to dissociate from the Jamaican verbal artistry that eventually blossomed into rap, but in the naamu-sayer we also see an early version of the hype man, a call-and-response that is ubiquitous in African and African-diasporic musics.

Return to text

18. Authenticity is of course defined differently in different genres. For example, where being the author of one’s own verses is central to hip hop, it is not central to country or rock music.

Return to text

19. Interestingly, this reference to “walkin’” represents another level of Signifyin(g) on his former ‘hood. “Walkin’” within a gang context evokes the “Crip Walk,” which originated in Compton in the 70s as a way for gang members to show affiliation, perform lookout duties, and mark kills with the Crip signature. Altered versions of the Crip Walk proliferated to gangs nationwide and became so widespread as to be used in dance battles—with sophisticated footwork required to literally spell out “Crips” with one’s feet—and ultimately became a form of stylized hip hop dance. In the video for “King Kunta,” Lamar performs a hip hop dance stylized after the “Crip Walk,” which is also clearly seen in the video for “i,” cementing the reference. Unsurprisingly, his dance is not as sophisticated as the original Crip Walk, probably to avoid specific gang affiliation. Nevertheless, with this strongly gang-affiliated dance move, which has been banned in schools (Hayasaki 2002), Lamar connects to his Compton roots: although Lamar avoided gang membership, gangs affected him, his family, and his peers, on a daily basis.

Return to text

20. Given “King Kunta’s” accumulative form, discussed above, accounting for each added layer would take this essay too far afield. Two prominent additional layers, however, are worth mentioning: the guitar, beginning in m. 33, plays quarter-notes, until its rock-oriented solo in the outro, and the record scratches, near the song’s end, play syncopated sixteenth-note rhythms.

Return to text

21. The hi hat does serve a role, but only as a “fill” every four measures.

Return to text

22. While his elevated position within the rap game is portrayed clearly in “King Kunta” with the line “Now I run the game, got the whole world talkin’, King Kunta,” other tracks on the album counteract this self-aggrandizement, clarifying his economic slave status. The first track, “Wesley’s Theory,” which lays out from the first verse to the second what young black entertainers encounter, from initial temptation to major systemic obstacles. In the first verse, Lamar raps from a deliberately naïve perspective that sees rap success as a means to quick riches: “When I get signed homie imma act a fool / hit the dance floor strobe lights in the room.” The second verse, rapped from the perspective of “Uncle Sam” or capitalist America, asks “What you want? You a house or a car? / Forty acres and a mule, a piano, a guitar? / Anything, see, my name is Uncle Sam, I’m your dog / Motherfucker you can live at the mall.” Here, “Forty acres and a mule” associates the material wealth (barely) possible through rap with General William Sherman’s Special Field Order No. 15, which aimed to secure a large swath of 40-acre plots along the Atlantic coast between South Carolina and Florida in 1865 for approximately 40,000 freed slaves; but it was soon nullified by President Andrew Johnson, and the land was returned to its original owners. In addition to falling victim to this sort of enticement, young rappers who are lucky enough to cash in inevitably face major obstacles to successful money management. The song’s title, “Wesley’s Theory,” references Wesley Snipes’s having served a three-year prison sentence for tax evasion. And the line “And when you hit the white house, do you / But remember, you ain’t pass economics in school / And everything you buy, taxes will deny / I’ll Wesley Snipe your ass before thirty-five” both alludes to a general lack of financial management skill (particularly in the face of a sudden monetary windfall) and suggests that they are also targets for anyone ranging from their own agents to the IRS. The sentiment going into “King Kunta,” then, is that although he (and by implication, other African American rappers) might “run the game” as a king, the reality is “that everybody wanna cut the legs off him” in the sense of keeping him a slave by preventing him from fleeing the plantation.

Return to text

23. From an intertextual standpoint, we can reflect back on Mausberg’s “Get Nekkid” in a similar light and find drastically differing results. “Get Nekkid” is a clear instance of verse-chorus form, thereby negating a direct association with double consciousness. Moreover, its lyrics are explicitly sexual, borderline sadomasochistic, in their description of Mausberg’s (and DJ Quik’s) sexual prowess. They thus represent what Krims calls “mack rap” (2000, 62). It is interesting to note that, whereas Lamar comments on social issues from a higher and later position within his career, Mausberg (rapping in 2000, the year of his death at age 21) raps squarely from within the game with content aimed at selling records, and could never shed the game’s expectations.

Return to text

24. Ogbar qualifies this claim, mentioning how child rappers like Lil’ Bow Wow and Lil’ Romeo, etc. have gone platinum with a teen target market (2007, 186).

Return to text

25. Over a decade old, these statistics require some qualification. First, one could conjecture that whites consume hip hop at a higher rate because they simply outnumber black people in the US. However, Rose contrasts this with the average R&B consumption gap, which was much smaller over the same period, at 8.1%. Second, the past decade has witnessed drastic changes in the format of how pop music is consumed, which in turn complicates how statistics are gathered. Not only has pop moved to more digital formats, along with the growing consumption of singles over albums, but the last decade has seen the rise of streaming services such as Pandora and Spotify, whose recent consumer demographic information is highly guarded.

Return to text

26. Ralph Ellison's Invisible Man begins with the main character participating in a battle royal. Afterward, all the participants are invited to grab as much cash as they can (what appear to be gold coins and crumpled up bills) from a rug, which they immediately realize has been electrified. And this is all for the entertainment of the city's upper class, including bankers, lawyers, doctors, a school superintendent, and even a “fashionable pastor” (1995, 13–26).

Return to text

Copyright Statement

Copyright © 2019 by the Society for Music Theory. All rights reserved.

[1] Copyrights for individual items published in Music Theory Online (MTO) are held by their authors. Items appearing in MTO may be saved and stored in electronic or paper form, and may be shared among individuals for purposes of scholarly research or discussion, but may not be republished in any form, electronic or print, without prior, written permission from the author(s), and advance notification of the editors of MTO.

[2] Any redistributed form of items published in MTO must include the following information in a form appropriate to the medium in which the items are to appear:

This item appeared in Music Theory Online in [VOLUME #, ISSUE #] on [DAY/MONTH/YEAR]. It was authored by [FULL NAME, EMAIL ADDRESS], with whose written permission it is reprinted here.

[3] Libraries may archive issues of MTO in electronic or paper form for public access so long as each issue is stored in its entirety, and no access fee is charged. Exceptions to these requirements must be approved in writing by the editors of MTO, who will act in accordance with the decisions of the Society for Music Theory.

This document and all portions thereof are protected by U.S. and international copyright laws. Material contained herein may be copied and/or distributed for research purposes only.

Prepared by Michael McClimon, Senior Editorial Assistant

Number of visits:

32928