Referents in the Palimpsests of Jazz: Disentangling Theme from Improvisation in Recordings of Standard Jazz Tunes*

Sean R. Smither

KEYWORDS: jazz, improvisation, standards, referent, recordings, ontology

ABSTRACT: Jazz analysts have long struggled with the ways in which tunes can be accounted for in analyses of musical structure. When analyzing the utterances jazz musicians make in an improvised performance, it is difficult to disentangle the musical elements related to what Jeff Pressing termed the “referent”—the improviser’s conceptualization of the tune—from those more freely improvised in the moment. Complicating this problem is the fact that standard jazz tunes themselves are not fixed structures with essential, immutable musical components; no definitive version exists of any given tune. Instead, tunes are flexible and malleable, permitting infinite variations.

In this article, I develop a methodology that provisionally disentangles jazz improvisations from the tunes on which they are based. I begin by theorizing the structure and function of various tune-referents before outlining a theory of referent defaults. I then present two case studies, one on melody and one on harmony, that examine the relations between different performances in order to arrive at a postulated referent for use in further analysis. Finally, I draw on anthropologist Timothy Ingold’s concept of textility to illuminate the nuanced ways that jazz improvisers engage with referents.

DOI: 10.30535/mto.30.3.6

Copyright © 2024 Society for Music Theory

1. The Problematics of Analyzing Standard Jazz Tunes

[1.1] Standard jazz tunes (from this point onward, simply “tunes”)—the compositions on which many jazz improvisations are based—are central to modern jazz practice. From jam sessions to the conservatory classroom to the jazz club stage, the tune is one of the most common frameworks for jazz improvisation. When jazz musicians play a tune, they participate in a living tradition grounded in Black American musical aesthetics, in which musical works are continually reinterpreted. The spirit of revision that animates this chain of reinterpretations, which Henry Louis Gates, Jr. (1988) terms “Signifyin(g),” is characterized by troping, transformation, inversion, intertextuality, and “repetition, with a signal difference” (51).(1) When Signifyin(g) on a tune, jazz musicians provide a sense of familiarity to their audiences, all while playing with, and in many cases fundamentally altering, that tune’s musical structure.

[1.2] When analyzing the utterances musicians make in an improvised performance, it is frequently difficult to disentangle the musical elements related to the tune from those that were more freely improvised in the moment. One issue complicating this problem is that informed listeners carry with them their own ideas about how a tune goes, and they rely on these intuitions to make sense of perceived transformations. Another is that transformations of jazz tunes reflect an important aesthetic principle in jazz improvisation: without a sense of what “the tune” is, listeners lack a point of comparison for perceiving and comprehending transformations. While no analytical method can fully account for the many ways that individual listeners might develop their sense of a tune’s identity, I argue in this article that a careful methodology can theorize the processes that underlie this comparative aspect of listening. In developing such a methodology, I am not interested in determining or problematizing the ontological status of works in jazz per se, nor do I wish to explicate the process by which ascriptions of work identity are made. Instead, my focus is on how subjective conceptualization of a tune’s musical structure—what Jeff Pressing (1984, 1998) termed a “referent”—affects the way that musical utterances are both generated and interpreted. For Pressing, a referent is “an underlying formal scheme or guiding image specific to a given piece, used by the improviser to facilitate the generation and editing of improvised behaviour on an intermediate time scale” (1984, 53). As such, referents provide an essential lens through which to view jazz improvisation and analysis.

[1.3] Due to the way that pre-composed and improvised elements blend together in performance, the referents that underpin jazz-tune performances can be difficult to determine.(2) Benjamin Givan (2002) compares the performance of a jazz tune to a palimpsest, a manuscript that has had its content partially scraped away to make room for new text, leaving only traces of the original text. Givan writes:

A jazz improvisation is like a palimpsest in sound. Beneath the music that reaches our ears lies a theme that simultaneously inspires and constrains the performer. From time to time traces may appear on the music’s surface that, like ghostly pentimentos, provide us with clues to the improviser’s underlying conception of the theme. . . [their] “model,” or “referent.” (2002, 41)(3)

In this article, I take Givan’s observation as the starting point for a methodology that aims to provisionally disentangle improvisations from the referents on which they are based. I begin by theorizing the structure and function of jazz tune-referents and then outlining a process wherein multiple recordings are compared to determine prototypical melodic and harmonic segments (referent defaults), which can be used to postulate a referent for analysis. I next demonstrate the utility of this method in two case studies: the first of these examines melodic referent defaults in Duke Ellington and Billy Strayhorn’s “Satin Doll,” while the second focuses on harmonic referent defaults in Richard Rodgers and Lorenz Hart’s “Isn’t It Romantic?” Finally, I illuminate the nuanced ways that jazz improvisers engage with referents by drawing on anthropologist Timothy Ingold’s (2010) concept of textility.

[1.4] Despite their centrality in the jazz tradition, there is surprisingly little agreement on what exactly tunes are; indeed, the complex ontology of jazz has seen an increasing amount of scholarly attention in recent years. In his 2017 article, Brian Kane advances a view of jazz tunes not as abstract works but as networks of performances. Writing against what he terms a “realist” account of jazz works typical of analytical philosophy, Kane argues that a jazz tune’s identity is contingent on the many relations established between different versions.(4) Music philosopher Eric Lewis, in his 2019 book Intents and Purposes, advocates for an ontological account of jazz and other African American musics based on George Lewis’s (1996) notion of Afrological aesthetics. Eric Lewis’s theory is sensitive to the intentions of improvisers and carefully delineates what is at stake—culturally, legally, and economically—in what might otherwise seem like banal ascriptions of work identity.

[1.5] Theorists and analysts of jazz have likewise struggled with the ways in which tunes can be accounted for in analyses of musical structure.(5) No definitive version exists of any given tune because tunes are not fixed structures with essential, immutable musical components.(6) Instead, tunes are flexible and malleable, permitting infinite variations.(7) Analyzing a tune without reference to a particular performance is inherently problematic. When faced with analyzing a performance of a tune, analysts can choose to represent the musical structure in several different ways. One approach is to simply select a published or otherwise widely available lead sheet. While doing so ensures that there is a citable source for the chord changes, the particular realization of the melody and harmony are likely to vary substantially in many cases from the lead-sheet representation. To avoid this disconnect, many authors opt instead to work directly from a transcription of a recording. There are two common ways that transcriptions are used to represent tunes: lead-sheet style transcriptions and full-texture transcriptions. Creators of lead-sheet style transcriptions begin with either a particular performance of a tune or an “authoritative recording” (Martin 2018b, [5.16]) of it, then transcribe an idealized version of the melody and changes into a lead-sheet format with (often simplified) melody and chord symbols.(8) In addition to prioritizing a particular instantiation over other versions that may also be representative of a tune’s structure, lead-sheet transcriptions may fail to provide the backdrop of expectations against which listeners are hearing the performance. This is because, in some cases, chord symbols may be drawn from other sources such as fakebooks or copyright deposits, failing to attend to the particularities in recordings; in other cases, details of melody and harmony may be left entirely unattributed.(9) As we will see, lead-sheet transcription can also be approached in a more nuanced way, wherein multiple recordings are consulted and an effort is made to present a provisional referent for a tune. In all cases, lead-sheet transcription requires the transcriber to distill a complex musical surface into an abstract set of chord symbols, pitches, and rhythm; it is therefore necessarily a reductive and interpretive act.

[1.6] Alternatively, to avoid dealing with the inherent challenges of determining chord symbols from a recording, some authors opt for a full-texture transcription that seeks to capture as many aspects of its harmony and melody as possible.(10) Although this approach may at first seem advantageous in circumventing the “underlying tune” problem by foregrounding instead the actual utterances of the musician(s), it invites other dilemmas. In addition to the well-established uncertainties and ambiguities associated with the subjectivity of transcription,(11) this kind of analysis often fails to take into account the implied backdrop of the tune; significant transformations of the tune by improvisers may not be acknowledged because they are understood as simply being part of the unfolding performance. That is to say, there is no distinction made between tune and performance. For example: if an improviser were to substitute a common chord for a less-common, alternate harmonization, the more common chord—which listeners are likely expecting and against which they are likely to hear the unfolding performance—would not be listed; only the alternative harmonization would be acknowledged.(12)

[1.7] The purpose of this discussion is not to criticize jazz analysts for insufficiently accounting for the ambiguities of tune identity. The problematics of analyzing jazz are well-established, and it is all too easy to become paralyzed by them. Moreover, as is well known, analyses depending on incomplete or ad-hoc representations of tunes are in many cases convincing and are certainly better than avoiding analyses of tunes and their performances

[1.8] Instead of basing jazz analysis on the problematic products of transcription, this article advocates for the use of a provisional musical structure devised for use in analysis that represents an informed approximation of a tune’s melodic, harmonic, and formal structure, which I term a postulated referent. Postulated referents can be specific to a given performance—and therefore an approximation of a referent for that particular performance—or they can be more general, in the case of analyzing a tune in the abstract. In either case, a postulated referent relies on the analysis of multiple versions of a tune. The requirement that multiple versions of a tune are surveyed is crucial because postulated referents ultimately simulate (and analytically stand in for) an improviser’s referent, which is influenced over time by exposure to many different renditions of a tune. Critically, a postulated referent is not the analyst’s own referent, nor is it meant to be an authentic representation of a specific improviser’s referent (which is, in most cases, ultimately unknowable). Postulated referents, rather, are methodically crafted to serve as a grounding foil for analysis, a means for distinguishing between “the tune” and transformations of that tune.

[1.9] In what follows, I will present a method for determining a postulated referent. There are a number of precedents to this method in which theorists have set out to create a provisional, idealized rendering of the tune involving a composite of several sources that are carefully weighed against one another.(14) For example, in detailing his process for examining Charlie Parker’s compositional output, Henry Martin writes:

The transcriptions and explanatory examples in this book are based on comparisons between various print versions and authoritative recordings (when available). In each case, I tried to arrive at a form of the piece that showed its most essential work-determinative properties. I also consulted other performances by Parker of the piece in question to see how committed he was to small inconsistencies or to try to hear certain parts more clearly. There will generally be differences among the choruses and (if relevant) the different takes. In such latter cases, I generally favored the master take, but used the other takes to help decide between essential and ad hoc elements. The same can be said for sections of pieces that are repeated within the same recording. An AABA tune, played twice, features six competing A sections. Which one, then, accurately designates “the actual A section” of the piece? Rather than being a problem, the opportunity to compare several A sections can be helpful in deciding upon the essential material, particularly the chord symbols of the “ideal changes.” (Martin 2020, 25–26)(15)

Similarly, Steven Strunk (2003, 2005) creates composite lead sheets based on comparison of various published lead sheets, recording transcriptions, and copyright deposits. “When these disagreed, as they did frequently,” Strunk writes, “I took all sources into consideration, generally giving greatest weight to my hearing of the recording” (2005, 302–3).(16) The philosophy behind these approaches is well articulated by Chris Stover (2013), who argues that to perform analysis is to “creatively define the analyzed object”—the tune—upon which the multiplicity of possible analyses are put to work in order to discover the “identity-as-multiplicity of a piece of music” (2–3).(17) The approach in the present article similarly aims not to create an ideal or composite lead sheet, but rather to postulate an underlying structure for a given performance, pulling apart the utterances of a performance and the implied musical structures on which they are based.

[1.10] In preparation for discussing this approach, it is necessary to lay out a few boundary conditions. This article concerns tunes that are typically played in a head–solos–head form. This is the most common overarching form in jazz improvisation, in which the melody and chord changes (together “the head”) are played at the start and end of the performance, with improvised solos taking place in between.(18) While both the solos and heads typically share a basic—but flexible—harmonic framework, the melodic content of a referent is only stated outright during the head. Some improvisers use the head melody as a launching-off point for their solos, though others disregard the melody.(19) Head melodies are often more easily remembered (and transcribed) in more vivid detail than harmonies, especially in the dense context of extended harmony typical of jazz practice. This provides us with clear, concrete transformations to identify and analyze. It is also uncommon for a tune’s melody and harmony to be heavily abstracted in the head because the head serves in part as a means of (re)familiarizing listeners with the tune. By contrast, the solo sections often feature more extensive harmonic alterations. Such alterations may be understood as transformations of the referent or as replacing parts of referents, with some transformations or replacements later becoming parts of the referent itself.(20) Either way, accounting for harmonic transformations in the solo sections significantly complicates the determination of referents; because of this, my focus in this article is primarily upon the head rather than the solos. The ways in which referents develop during solo sections may, however, serve as fertile ground for future studies of jazz referents.

[1.11] The present study shares some similarities with the burgeoning field of corpus studies.(21) Similar to corpus-based research, I propose an analytical method that references a dataset (defined below as an avant-texte) and then uses information gleaned from that dataset to gain a sense of what is and is not common. There are important differences, however. Although there will always be an inevitable degree of subjectivity involved in any research, studies of large corpora often seek to circumnavigate this problem by ensuring that the dataset is as large as practically possible and can therefore statistically capture information about the entire dataset as reliably as possible. My aims in this present study are different: rather than capturing what is most or least common among all versions of a tune, I seek to gain a sense of how individual improvisers conceptualize tunes based on their experience with particular versions. There are several important aspects of this process that large-scale corpus studies cannot easily capture. First, improvisers are usually only familiar with a small, personalized selection of recordings of a given tune. Second, improviser’s conceptualizations are filtered through their own understandings of musical structure, as mediated by their own training and lived experience. Perhaps most important, however, is that there is no existing method that would allow corpus studies to distinguish between elements that are part of a tune and those that are not—that is, corpus studies cannot distinguish between layers of the palimpsest. By considering how individual improvisers come to conceptualize tunes, this article endeavors to develop such a method.

[1.12] Because I am primarily interested in how individual improvisers conceptualize musical structure, it is important to acknowledge the role of subjectivity and self-examination in this article.(22) Throughout the discussion to follow, I will rely on my own lived experience as a jazz musician and educator to explain in detail the processes by which improvisers sift through recordings and determine which aspects are, to them, part of the implied referent and which represent departures from that implied referent.(23) This emphasis on my own knowledge and experience serves two complementary purposes, the first being to acknowledge that determinations of referents are subjective and cannot be easily captured on a larger scale. The other is to partially document the phenomenon of intersubjectivity, which stems from certain conceptual and theoretical apparatuses being shared throughout the jazz community.(24) In order to both highlight the subjective nature of the process and avoid making universalizing claims, I will describe the conceptualizations that guide my thought processes. While my subjective observations are not representative of how all jazz musicians will conceptualize musical structure, they should be read as neither atypical nor especially personal.

2. Representing Referents

[2.1] Referents, as formulated by Jeff Pressing, represent a wide-ranging category, which may include “a musical theme, a motive, a mood, a picture, an emotion, a structure in space or time, a guiding visual image, a physical process, a story, an attribute, a movement quality, a poem, a social situation, an animal—virtually any coherent image which allows the improviser a sense of engagement and continuity” (1984, 346). In practice, however, Pressing treats referents in musical improvisation as musical structures or motives that serve as a source of musical material. When referents have a time-keeping dimension, Pressing characterizes them as “in-time,” as opposed to “out-of-time”; examples of in-time referents include a chord progression with a defined harmonic rhythm, a repeating theme/variations format, or a song form. Despite the centrality of referents to improvisation, Pressing does not devote much space to discussing what referents are or might be; he instead uses them as a way of qualifying different kinds of improvisational processes. The closest he comes to a comprehensive description of them is in his list of various types of improvisations and the referent types underlying them. Ornamented melodies, for example, take a melody as a referent; “melody types” (as typified by Indian rāga, Arabic maqām, Persian dastgāh) take pitch collections and/or sets of melodic conventions as a basis for melodic construction; thoroughbass derives its referent from a composed bass line along with figures; and theme and variation form takes a harmonic progression, melody, and various rhythmic features as a referent. A variety of different types of referents are used in jazz practice, including standard tunes (often represented by lead sheets), big-band charts, written arrangements of tunes, motivic material, and flexible ostinati.(25) Tunes, the primary focus of this article, are arguably the most common kind of referent in mainstream jazz history and practice. My decision to focus on tunes is not meant to imply that other kinds of referents are less valuable or interesting. It rather reflects that fact that owing to the central role tunes play in much mainstream jazz practice and education, they represent a useful starting place for theorizing referent structure and function. Furthermore, as I will argue, conceptualizing tunes as referents helps clarify how tunes influence musical structure in jazz.

[2.2] Among the most common ways of representing jazz tunes is a lead sheet, which features only a melody and chord changes. Jazz improvisers frequently make use of lead sheets; thus, they can serve as referents. However, the musical content of a lead sheet is understood by most jazz musicians to be a fixed rendition of an inherently flexible structure, offering a possible but not definitive interpretation of the tune. Lead sheets may therefore differ substantially from an improviser’s referent, which is often a more personal conceptualization of a tune’s structure. Referents may also evolve and adapt as a single, live performance unfolds, particularly if an improviser notices that another musician is using a specific set of chord changes or a well-known melodic variant.

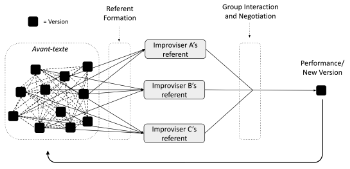

Example 1. Diagram showing the relationship between avant-textes and referents

(click to enlarge)

[2.3] Referents are grounded in the network of experiences an improviser has with the tune over time. In my previous work on this subject, I drew on the literature of genetic criticism and musical sketch studies and theorized this network as an avant-texte.(26) To be specific, the instantiations of a tune—performances, recordings, lead sheets, arrangements, and so on—and the relations between those instantiations together comprise an improviser’s avant-texte. An improviser’s referent for a given standard will be deeply influenced by their avant-texte and can be continually developed and revised as the improviser becomes familiar with more versions. Example 1 shows a diagram of avant-texte–referent relations; a continuous loop sets the tune in an endless process of becoming.(27) Because referents are in constant dialogue with the avant-texte that informs them, and because the avant-texte is a continuously evolving collection of sources with which the improviser is familiar, referents are often in a state of flux. The plurality of the avant-texte informs the (flexible, always evolving) singularity of the referent.

[2.4] Whether or not they are improvisers, listeners will develop referents for the tunes they come to know. Unlike improvisers, whose referents are put to use as a central aspect of the improvisational process, non-improvising listeners are more likely to use their referents for comparison, to recognize a tune and understand how it is transformed in a performance.(28) Among the core claims of this article is that listeners—both improvisers and non-improvisers—sift through performances of tunes, comparing how the tune is represented in a performance to their own referent of the piece. Incongruities that emerge between a listener’s referent and the sounding music can be sites of musical meaning and expressivity. This experience will necessarily differ somewhat between improvisers—whose referents are involved in poietic processes—and non-improvising listeners, whose referents serve an esthesic function.(29) I focus primarily on improvisers’ perspectives in this article for a number of reasons. Doing so opens up several useful lines of inquiry into how conceptualizations of tunes proliferate and change over time; in addition, it enables us to closely engage with the mechanics of referent formation and use. Improvisers use referents in traceable ways: the use of a referent may result in a recorded performance that can be analyzed. Examining referents from an improviser’s perspective thus enables us to consider both the poietic and esthesic processes.

[2.5] In addition to tunes, arrangements constitute a central (related) category of referent in modern jazz practice. For this present article, I define an arrangement as anything about a given performance that is fixed before that performance begins, as agreed upon by members of the ensemble.(30) Arrangements vary widely in complexity: in some cases, every utterance of a performance, down to the finest level of detail, may be arranged, while in others very few details may be predetermined. Arrangements often involve a notated score, especially those organized for a large ensemble; however, this is not always the case. Small-ensemble arrangements especially may be communicated verbally or aurally. Whereas written big-band arrangements often feature ontologically thick, complex harmonizations of the melody, countermelodies, horn textures, solis, and so on, small-ensemble arrangements are often comparatively thin,(31) perhaps featuring a particular melodic rhythm, contrapuntal line and/or harmonization for the melody, specified chord changes, and ensemble “hits” that the rhythm section emphasizes together.(32) Even in such cases, minor deviations from the arrangement—especially creative ones such as reharmonizations, melodic embellishments, and antiphonal interpolations—may be considered acceptable or even desirable. Nonetheless, the arrangement retains an identity separate from, but intertwined with, the tune.

[2.6] An arrangement represents a special kind of referent, one with specific conditions attached that may constrain the kinds of improvisational decisions the performer makes and the ways those decisions are interpreted.(33) A performer, in this case, may develop two referents for the same tune: a tune-referent and an arrangement-referent.(34) It is important here to distinguish between these two referent types, because arrangements are typically performance- or group-specific and therefore represent a different kind of knowledge structure from tune-referents. For example, being familiar with Gerald Marks and Seymour Simons’ popular tune “All of Me” is different from knowing the details of the Count Basie Orchestra’s well-known arrangement of the same tune. If “All of Me” is called at a jam session, there will generally be no expectation to follow any particular arrangement; the referent that players refer to will instead rely strongly on each improviser’s individual knowledge of the tune. Conversely, if an ensemble is following an arrangement, the referent that players use will be based on the arrangement and thus less flexible. Under such conditions, an utterance that does not follow the arrangement-referent is unambiguously considered by both the player and the ensemble to be an error rather than an intentional improvisational decision.(35)

[2.7] Whereas an arrangement referent is understood by the improviser to be a special case constituted by arrangement features, a tune-referent stands apart from this as a set of defaults (discussed in more detail below), representing what the improviser considers to be “the tune itself.” As such, tune-referents are closely related to the rest of an improviser’s knowledge base (Pressing 1998, Berkowitz 2010), which comprises the collection of learned formulas and gestures, techniques, music-theoretical knowledge, and so on, that aids an improviser in generating improvised utterances.(36) The structural qualities of a referent are arguably inseparable from the ways of knowing that help us define those structural qualities in the first place.(37) Referents are often composed of patterns from the knowledge base, ordered and applied in specific ways.

[2.8] Despite the inherent difficulties associated with studying referents, there are several reasons why we might wish to engage with them. As Givan argues, “an awareness of the omnipresent model [referent] is a sine qua non of competent performance—and a vital, if not essential, element of informed listening—in most jazz styles that emerged between 1920 and 1950” (2002, 41). If we are interested in understanding how an improviser arrives at particular improvisational decisions, or how a listener makes sense of those improvisational decisions, an understanding of what might constitute the improviser’s referent is a crucial piece of the puzzle. As we listen to and analyze jazz, we attribute creative choices to improvisers based on the relation between their utterances and the assumed musical structure of the underlying tune. These creative choices can be made more clear if we can arrive at an understanding, however provisional, of the improviser’s referent. By sketching out a postulated referent based on a given performance, we can gain a clearer sense of what a listener might hear as the tune or arrangement in that performance. This inferred referent provides a basis for comparison between the tune and the sounding improvisation: transformations in the unfolding improvisation are made salient in relief against the inferred referent. This process of dialogic comparison is a central feature of several African American aesthetic frameworks, including Gates’s Signifyin(g) (1988) and Samuel A. Floyd’s Call–Response (1991, 276), and as such is a core concern for most jazz musicians and audiences. Put simply, we can only make sense of a transformation if we know what is being transformed. While we can never truly know what exactly constitutes an improviser’s referent in any given performance, a postulated referent makes no claim of being definitive. Rather, a postulated referent is simply what a listener might reasonably infer as the possible musical structure of the tune or arrangement informing the performance.

3. Referent Defaults

[3.1] To construct a postulated referent, we will need to pin down a musical structure for a given performance. One concrete way that we can begin to do this is through what I term referent defaults. My adoption of this term is inspired by its use in Formenlehre writings, especially those by James Hepokoski and Warren Darcy.(38) Their Sonata Theory has many resonances with jazz ontology: their dialogic approach to the analysis of form seeks to understand how prototypes emerge from the relationships between individual nodes of a large network of eighteenth-century sonatas that share certain compositional procedures and formal scripts.(39) Defaults comprise one of the core tenets of this dialogic framework and are conceived in Sonata Theory using a hierarchical level system:

First-level defaults were almost reflexive choices—the things that most composers might do as a matter of course, the first option that would normally occur to them. More than that: not to activate a first-level-default option [. . . ] would require a more fully conscious decision—the striving for an effect different from that provided by the usual choice. An additional implication is that not to choose the first-level default would in most cases lead one to consider what the second-level default was—the next most obvious choice. If that, too, were rejected, then one was next invited to consider the third-level default (if it existed), and so on. (Hepokoski and Darcy 2006, 10)

Because they are the most common, first-level defaults will usually register to listeners as unmarked, while second-level defaults are slightly more marked, and third-level defaults are more marked still.(40) While the frequency with which a particular option occurs within a given corpus may affect whether and to what extent that option is understood as a default, defaults are not merely measures of frequency. Hepokoski and Darcy imbue the implementation of defaults with an air of compositional automaticity and reserve the act of deviation from defaults for moments of creative intentionality. Although the authors highlight the creative agency of the composer, defaults are not compositional acts but rather exist in the domain of the prototype. By identifying multiple levels of defaults, Hepokoski and Darcy ensure that the prototypes they develop are not overly limited and are able to contain multiple concrete exemplars.

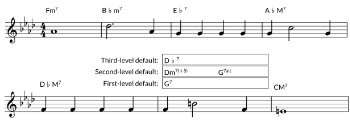

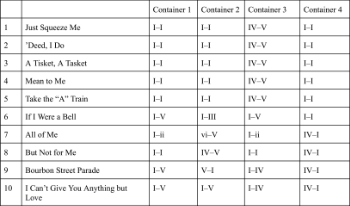

Example 2. Illustration of my weighted harmonic defaults in m. 5 of Kern’s “All the Things You Are”

(click to enlarge)

[3.2] The terminology borrowed from Hepokoski and Darcy carries much the same meaning when applied to tune-referents. In this context, defaults describe the most thoroughly internalized, automatic version of a particular passage of a given tune. Improvisers may store in memory multiple concrete exemplars as part of their referent, which may be weighted in terms of first-, second-, and third-level defaults (and so on). Example 2 shows my personal set of harmonic defaults for the chord in m. 6 of Jerome Kern’s “All the Things You Are.” In the example, I consider

Example 3. Illustration of my non-weighted harmonic defaults in m. 2 of Rodgers and Hart’s “Have You Met Miss Jones?”

(click to enlarge)

Unlike in Hepokoski and Darcy’s theorization, referent defaults in my approach need not always be arranged hierarchically: in some cases, there are simply multiple variations that are weighted similarly, with no one variation seeming any more definitive or basic than any other. For example, in Richard Rodgers and Lorenz Hart’s “Have You Met Miss Jones” (Example 3) my harmonic default for m. 2 is evenly weighted between an applied dominant chord (

[3.3] Several criteria will contribute to whether and how a listener organizes a family of defaults hierarchically. One is the frequency with which a particular default occurs in an avant-texte: features that occur frequently would seem to suggest that other musicians also consider the choice as a default, while rarer choices are more likely to correlate with individualistic expressions. If a listener is repeatedly exposed to the passing diminished

[3.4] In tune-based jazz as in sonata theory, referent defaults are grounded in the similarities between various instantiations of the prototype, are conditioned by subjective understandings of musical structure, and are particular to a given composer/improviser.(45) The fact that different individuals have different—but often overlapping—avant-textes and ways of conceptualizing musical structure means that referent defaults are not necessarily shared.(46) As such, referent defaults do not always tell us anything definitive about how a piece will be performed. Returning to Example 2, if I play measure 5 of “All the Things You Are,” I may use any of my defaults for the

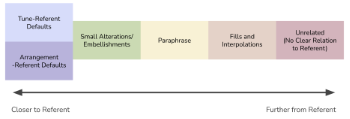

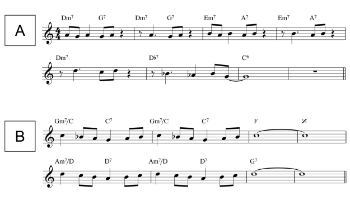

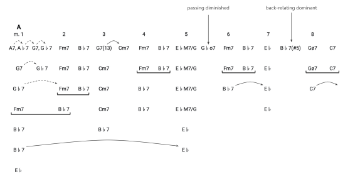

Example 4. Spectrum of relations between performed melody and referent defaults

(click to enlarge)

[3.5] I argue that listeners subconsciously sort segments of melodies and harmonies as they listen and then use these determinations to help build and refine their referent defaults. Melodic segments may be sorted into categories like those shown in Example 4. (Harmonies, as will be discussed in more detail in Section 5, may be sorted by perceived structural dependency.) The determinations appearing towards the left side of the spectrum have greater impact on tune-referent formation, while those appearing towards the right side of the spectrum are less likely to be heard as fundamental to the tune. Segments that are categorized as somewhere in the middle are more ambiguous and may be heard only as second- or third-level defaults. These determinations are likely to be strengthened by the broadness of one’s familiarity with many versions of the tune, which is to say that the fewer versions a listener has heard, the less confidently such determinations can be made. Initially, a listener may privilege the first version with which they become familiar. Yet as the listener’s avant-texte grows, that first version will become better contextualized, and more nuanced defaults may start to emerge.

[3.6] The melodic spectrum in Example 4 resembles a similar continuum of “levels of intensity” advanced by saxophonist Lee Konitz (Berliner 1994, 67–71), which runs from interpretation to improvisation. It similarly resonates with the varying degrees of freedom in improvisation described by Leslie Tilley (2019) in her theorization of formulaic improvisation.(47) Like Konitz’s and Tilley’s continua, the spectrum in Example 4 suggests that utterances may be heard as representing a pre-composed musical idea, as an untethered improvisation, or as something in between. If a melodic utterance seems to correspond with the most straightforward way of playing a melody, I label this as a “tune-referent default” (shown in blue). In cases where an arrangement is used, listeners may instead hear utterances as part of the arrangement, and therefore as “arrangement defaults” (shown in purple), rather than as representative of an underlying tune-referent. Both of these categories indicate that the analyst hears no embellishment of the tune. The next category to the right, “small alterations/embellishments” (shown in green), indicates that the analyst hears some minor alterations to an implied referent, and is therefore at a level of remove from the referent. Such alterations may include small rhythmic/metric displacements, melodic ornaments, a substituted pitch here or there, and so on. “Paraphrase,” colored in yellow, indicates a greater sense of remove from the referent while still suggesting some attachment to the original passage. Notes and even entire gestures may be added or removed, provided that the resulting utterances are still recognizable as a variant of an implied referent default. The remaining two categories, “fills and interpolations” (in orange) and “unrelated (no clear relation to referent)” (in red), describe utterances that are distinct from the material of the implied referent. “Fills and interpolations” describe any utterances that fill in rests in the tune’s melody; these utterances do not represent the tune, but they also do not disrupt the tune’s presentation. And last, “Unrelated” utterances replace segments of the tune’s melody with melodic material that bears no clear resemblance to the tune. It is important to emphasize that these determinations represent how an analyst or listener hears and understands the sounding music in relation to an implied referent. If an individual hears an utterance as representative of the improviser’s referent—and therefore representative of the improviser’s conceptualization of the tune’s identity—then the utterance may be more likely to shape the individual’s own referent defaults. Admittedly, the lines between these categories are fuzzy, and making such determinations is necessarily subjective. Nevertheless, these determinations can help to explain how individuals decide what in a given performance they hear as part of “the tune.” If an individual learns a tune by hearing performances of it (rather than reading a score)—something which is arguably the case for most listeners—these determinations help to crystallize that individual’s referent for the tune.

4. Melodic Referent Defaults in Ellington and Strayhorn’s “Satin Doll”

[4.1] As I have argued, referents are built over time and depend on the individual’s avant-texte. To provide a glimpse into this process, in this section I will demonstrate how my own referent for Duke Ellington and Billy Strayhorn’s standard tune “Satin Doll” relates to the versions of the tune with which I am familiar. There are several advantages in choosing to examine my own referent. First, I can readily assess my own understandings of musical structure. To return to Example 2 above, I understand

[4.2] Written in 1953, “Satin Doll” was one of the last popular hits for Ellington and Strayhorn. Its chord changes involve a number of well-known schemas, primarily ii–Vs in the A sections and a stock bridge, sometimes called a “Montgomery–Ward bridge,” in the B section.(50) The melody is simple and catchy, relying on only a few motives, though the 1953 premiere recording by Ellington’s orchestra thickens this melody through Strayhorn’s lush harmonizations.(51) Perhaps because of how simple and familiar the harmonic patterns are, performances do not tend to depart significantly from the chord changes of the original version. Conversely, the sparse melody has been adapted in a variety of ways. This makes the tune an optimal case study for determining melodic referent defaults.

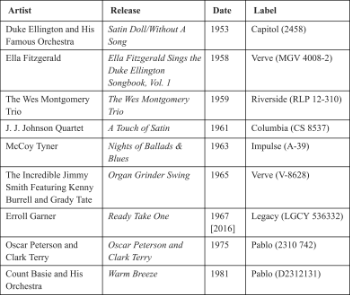

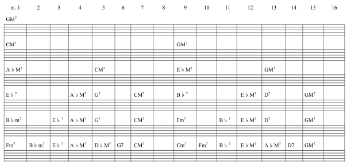

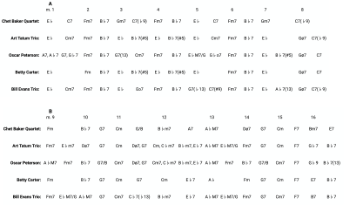

Example 5. My avant-texte for “Satin Doll” (Ellington and Strayhorn)

(click to enlarge)

Example 6. Lead sheet of my referent for “Satin Doll”, based on the avant-texte in Example 5

(click to enlarge)

[4.3] Example 5 lists the nine recordings of the tune with which I am most familiar. They span a wide array of performance formats, from duo to big band, but are not necessarily representative of the many versions of the tune that exist. My first-level referent defaults for the tune are shown in lead-sheet form in Example 6. There are no lead sheets in my avant-texte, because I did not reference a lead sheet when learning the tune. This is not an uncommon practice amongst jazz musicians. Because most well-known lead sheets tend to include errors or idiosyncrasies, improvisers typically rely on recordings and even on-the-fly performances to learn a tune.(52) If a lead sheet is used, it is mostly as a launching-off point, with recordings being given more weight. Nonetheless, my referent defaults feature a musical uniformity similar to an edited fakebook lead sheet. In some ways, both referents and lead sheets may be likened to an “averaged out” rendition of the tune. This “averaging out” of different versions is in both cases weighted by various preference rules and broader aesthetic goals. One common goal of both referents and fakebook lead sheets is the recognition and privileging of clear motivic and harmonic parallelisms. For example, the rhythms of mm. 1 and 3 in Example 6 are identical. While these particular rhythms in this tune are not always represented in this way (as discussed in more detail below), the rhythms of mm. 1 and 3 are typically similar or identical within a given rendition of “Satin Doll,” a reflection of the transpositional motivic relationship between them. Nonetheless, there are several crucial distinctions that must be made between fakebook lead sheets and referent defaults. Fakebook lead sheets often use straightforward, “averaged out” melodic rhythms and harmonies. This supports the primary goal of fakebook lead sheets, that being to provide visual clarity and simplicity so that improvisers can quickly read a melody, altering and embellishing it on the fly. It has a notable disadvantage, though, which is that many lead-sheet melodies sound awkward when played as written. A referent default, on the other hand, serves as a kind of minimally acceptable starting point. Although flexible and changeable, a referent default represents the tune as an improviser might most simply play it. Although the defaults are drawn from a listener’s avant-texte, they do not necessarily represent a clear midpoint between different entries in the avant-texte.

Example 7. Lead sheet transcription and reduction of the head in Ellington’s premiere recording of “Satin Doll”

(click to enlarge)

[4.4] As one might expect, my lead-sheet representation differs from Ellington’s premiere 1953 recording, transcribed in Example 7. Most of these differences are small: a note here or there is a bit early or a bit late, a harmony is substituted with a common reharmonization, and so on. Although these minor differences may seem insignificant, it is worth noting that they could pose problems in the context of a performance. If two improvisers with different referents improvise together, the differences between their referents may need to be reconciled, lest the resulting performance come across as messy and disorganized.(53) The implications of such minor differences can likewise extend to debates regarding authenticity, creativity, originality, and even musicality.

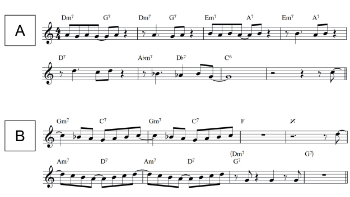

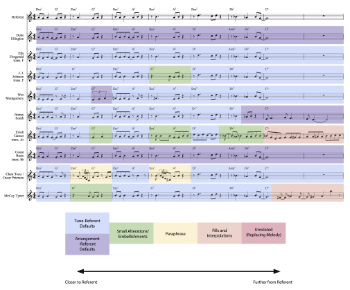

Example 8. Transcriptions of the first A and B sections in each of the recordings of the “Satin Doll” avant-texte, compared against my referent

(click to enlarge and see the rest)

[4.5] In order to figure out what is responsible for the differences between the lead sheets shown in Examples 6 and 7, let us more closely examine the performances from my avant-texte in Example 5. Transcriptions of the first A and B sections of each recording are shown in Example 8. Some segments of these recorded melodies represent attempts to play the melody straightforwardly; other segments embellish the melody, and others still simply depart from the melody entirely with flights of improvisation.

[4.6] Example 9 categorizes segments of the A-section melodies according to how I perceive them relating to my referent in terms of the color-coded categories of Example 4. The majority of these A-section melodies seem to represent the tune straightforwardly (see blue coloring). In cases where there is an arrangement that the ensemble is following, features of the arrangement are colored purple. This can usually be deduced by multiple players in the ensemble playing the same exact melodic rhythms together (especially when the melody is harmonized), as in the Ellington and Basie recordings, or when there are stop-time passages or rhythmic hits played by the entire ensemble, such as in the Jimmy Smith and Wes Montgomery recordings. It is true that events of this type might be seen to blur the boundaries between tune-referent defaults and arrangement-referent defaults. However, the two types of defaults serve a similar purpose, namely presenting the melody in a more-or-less fixed manner; thus, my system categorizes them in a similar way.(54) A few passages feature small alterations and embellishments to the melody (colored in green). Erroll Garner’s ornate take, for example, is replete with such alterations. Other possibilities include more openly paraphrased melodies (colored yellow), such as those played by Clark Terry in his performance with Oscar Peterson, and interpolations that fill in the space left in the last two measures of the phrase (colored orange).

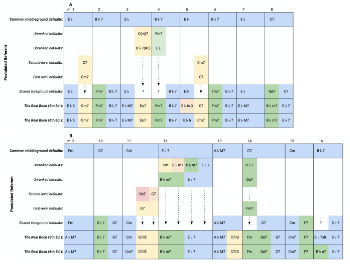

Example 9. Relations of A-section melodies of “Satin Doll” to referent defaults and arrangement features (click to enlarge) | Example 10. Relations of B-section melodies of “Satin Doll” to referent defaults and arrangement features (click to enlarge) |

[4.7] Although none of the A sections feature unrelated improvisational flights replacing the melody, this technique—colored in red—is much more common in the B sections shown in Example 10. The extent to which these B-section melodies represent referent defaults is more polarized than in the A section. For the most part, the B section is either played straight (as in the Ellington, Fitzgerald, Johnson, Montgomery, and Basie versions) or is heavily altered using a variety of techniques from across the spectrum; see, for example, the multicolored Smith, Garner, Terry/Peterson, and Tyner versions.

Example 11. A postulated referent for Burrell’s B section of “Satin Doll,” drawn from a comparative analysis of Burrell’s and Johnson’s recordings

(click to enlarge)

[4.8] With the aid of these determinations, we can postulate a referent for analysis. Take, for example, guitarist Kenny Burrell’s rendition of the B section on Jimmy Smith’s recording (Example 11). My analysis of Burrell’s interpretation includes only a few short passages of what I hear as referent defaults (based on comparisons with the corresponding passages in Example 10), while the rest is made up of alterations, short fills, and improvised additions. How might these determinations shape a postulated referent? If we are hoping to gain a sense of Burrell’s melodic referent default, we can discard the passages marked “unrelated” (colored red in Example 11) and “fills” (colored orange), neither of which is likely to shed light on Burrell’s conception of the tune’s melody. The strategy, rather, entails concentrating on the excerpts categorized as small alterations/embellishments (in green) and paraphrases (in yellow, though none of these exist in the Burrell excerpt); and comparing these passages to similar renditions in the avante-texte. For example, the rhythms of the passages I have labeled as “referent defaults” (in blue) are the same as those of J. J. Johnson’s recording, which emphasizes the “and” of 2 and 4 at the climax and nadir of each segment. Since these rhythms tend to be consistent in most renditions of the B sections in Example 10, we might conclude from this that these rhythms represent a reasonable referent for this passage.(55) Combining these rhythms with the harmonic idiosyncrasies of Smith’s recording, together with Smith’s more straightforward rendition of the A section, we can postulate a referent for the performance (Example 10, bottom staff). Importantly, this postulation does not claim to represent Burrell’s actual referent for “Satin Doll,” nor does it purport to be the most widely held referent for this segment amongst audiences. Instead, it is the referent that this passage of this recording subjectively implies when in dialogue with the other recordings from my avant-texte.

[4.9] By carefully comparing existing versions of the tune—or in other words, by disentangling the layers of the jazz-tune palimpsest—we are able to fashion together a postulated referent representing an estimation of the musical structure the improvisers are starting from. While a postulated referent is by definition speculative and provisional, it is a useful resource for specifying what we mean when we refer to “the tune” in the course of an analysis, especially when “the tune” serves as a comparison point for transformations occurring in the sounding music.

5. Harmonic Referent Defaults in Rodgers and Hart’s “Isn’t It Romantic?”

[5.1] Referent defaults become significantly more complex and difficult to work with when we consider harmonic variation between versions.(56) Whereas fakebook lead sheets represent tunes as a singular melody and set of chord changes, in practice harmonies vary considerably between performances. While a comprehensive account of harmonic practices in jazz is out of the scope of this article, it is worth discussing here some of the ways that jazz harmony may be conceptualized by improvisers, in order to shed light on the role harmony plays in tune-referents.

[5.2] Many accounts of jazz improvisation rest on the assumption that one of the fundamental activities performed by jazz musicians is fitting a melody to a static chord progression.(57) It is easy to see why this view is so prevalent: tunes are, after all, often described as consisting of a melody and chord changes, and once the performance has moved from the head to the solos section, the chord changes remain as the primary improvisational constraint. Indeed, the notion of the chord changes can overly reify the concept, putting undue weight on the fixity implied by that telling definite article. This reification is furthered by lead-sheet representations of tunes, where the repeated visual experience of reading discrete chord symbols in a score reinforces the idea that a tune’s very identity is based on fixed sequences of chords.(58)

[5.3] While improvisers do often speak about chord changes as though some fixed, “correct” version of the changes exists,(59) reharmonization is a ubiquitous part of jazz harmonic practice. There are many kinds of reharmonization techniques, ranging from simple one-to-one chord replacements (e.g., tritone substitutes) to lengthier and more elaborate designs (e.g., “Coltrane changes”), to more idiosyncratic approaches.(60) Reharmonization is often cast as a process that begins with a given chord progression that improvisers alter through chord substitutions and interpolations. There are two notable problems with this view, however. First, as we have seen, there is no single definitive set of chord changes for a given tune. The distinction between reharmonization and harmonic default can usually only be unambiguously made with regard to the contrast between an improviser’s referent and the performance that results from it. Second and more substantially, the harmonic content of a tune is, I argue, better understood not as a sequence of chords but rather as part of a larger harmonic-metric-formal complex, wherein harmonic utterances are defined by the role they play in a larger harmonic-formal plan rather than in relation to a static chord progression.

Example 12. Terefenko’s Phrase Model 4 and accompanying table indicating types of harmonic departure

(click to enlarge)

[5.4] My account here is influenced by Dariusz Terefenko’s (2004) work on phrase models in standard tunes.(61) Terefenko defines a phrase model as a description of a phrase’s underlying melodic, contrapuntal, and harmonic structure. “In the case of standard tunes,” he writes, “there appear to be a finite number of typical phrase models, each with its own distinctive melodic structure, essential jazz counterpoint, and supporting harmonies” (Terefenko 2004, 3).(62) Terefenko provides thirteen distinct phrase models, each represented as a quasi-Schenkerian, deep-middleground structure supplemented with harmonies in the form of Roman numerals. Each phrase model is divided into a tripartite scheme comprising an “initial projection” followed by a “harmonic departure” and finally “cadential closure.” These phrase models may be truncated, as for example when a tune’s bridge skips the initial projection of a stable tonality and begins instead with a harmonic departure, or when an opening phrase avoids cadential closure. Consider Terefenko’s fourth phrase model, shown in Example 12. The accompanying table below the model explains what key areas are emphasized during the harmonic departure, if one occurs, in select examples. (Note that the “harmonic departure” section is left unspecified in the model itself.) Although they are not necessarily designed to capture how improvisers conceptualize the musical structure of tunes, Terefenko’s phrase models serve both to pin down features that listeners are likely to consider essential and to relate those features to each other in a holistic fashion. Phrase models may be thought of as being akin to modules in a larger prototype, where each module contains certain melodic and harmonic referent defaults. Terefenko’s model is notable for 1) refusing to separate harmony from melodic and contrapuntal elements, 2) linking those elements to the notion of a prototypical musical phrase, and 3) zooming out to more general characterizations of tonal movement and formal function as applied to such phrases. Terefenko is thus able to move beyond oversimplified conceptions of tunes as chord sequences, towards a nuanced modeling that more closely approximates the kinds of structures an improviser must consider on an “intermediate time scale” (Pressing 1984, 53).

Example 13. Henry Martin’s demonstration of how prolongation-by-arrival results in hierarchical relationships in the chord changes of the first two A sections of Jerome Kern’s “All the Things You Are”

(click to enlarge)

[5.5] Like Terefenko’s approach, Schenkerian accounts of jazz also center on hierarchical conceptualizations of harmony.(63) For example, Henry Martin (1988) argues that many circle-of-fifths-based harmonic progressions result in “prolongation-by-arrival,” generating a clear hierarchical relationship between pairs of chords at various structural levels; Martin’s analysis of Jerome Kern’s “All the Things You Are” is shown in Example 13. The resulting hierarchy ensures that certain harmonies are more structurally essential than others and therefore act as harmonic anchors. Improvisers can move between structural levels based on the degree of harmonic detail they wish to use. A similar conception is expressed by George Russell in his description of distinct improvisational styles associated with tenor saxophonists Lester Young and Coleman Hawkins: “Coleman Hawkins would be a local steamboat that stopped at every town and conveyed the local color. Each town would be a chord

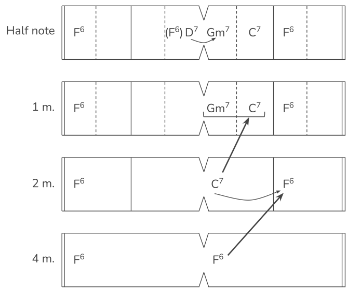

Example 14. Geyer’s essential harmonic motions in section-length formal containers for ten standard tunes

(click to enlarge)

[5.6] Another hierarchical approach informing my method is put forth by Benjamin Geyer (2021). Taking inspiration from Steven Strunk’s (1979) layered approach to bebop harmony, Geyer examines how the harmonic plan of a tune is layered within a metric and formal hierarchy. For Geyer, formal containers “mark the boundaries of harmonic motions

Example 15. Geyer’s demonstration of hierarchical relationships in Ellington’s “Just Squeeze Me”

(click to enlarge)

[5.7] For Geyer, departure and arrival chords become foundational in a larger hierarchy, with harmonic structural levels coordinated to levels of the metric hierarchy. In his analysis of Ellington’s “Just Squeeze Me” (Example 15), Geyer shows a chain of embellishment appearing as one moves up to the smaller time-span levels of the metric hierarchy. The essential

As jazz musicians improvise over this part of “Just Squeeze Me,” they will usually play the first and lastF6 , which make up the essential harmonic motion as arrival and departure chords. Beyond that, there is a lot of room for flexibility in how musicians will elaborate this essential motion into a foreground progression. TheD7 , as the shallowest elaboration, can simply be omitted with very little effect. Or the same kinds of operations that we labelled with curved arrows [dominant-tonic relations] and square brackets [ii–V schemas] can be applied in all kinds of interesting ways. (2021, 107–8)

Like Martin’s hierarchical derivation, Geyer’s theorization encompasses several structural levels of harmony. Both Geyer’s and Terefenko’s works are largely pedagogically oriented, suggesting that these level-based approaches reflect how jazz musicians tend to conceptualize musical structure. In the analysis that follows, we will utilize these level-based approaches to compare several versions of Richard Rodgers and Lorenz Hart’s “Isn’t It Romantic?,” which in turn will allow us to create postulated referents based on referent defaults at multiple structural levels.

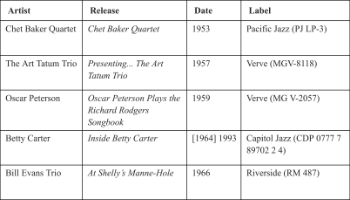

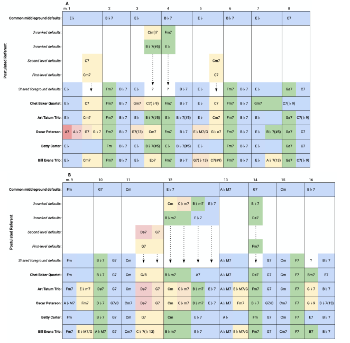

Example 16. A limited avant-texte for “Isn’t It Romantic?” (Rodgers and Hart)

(click to enlarge)

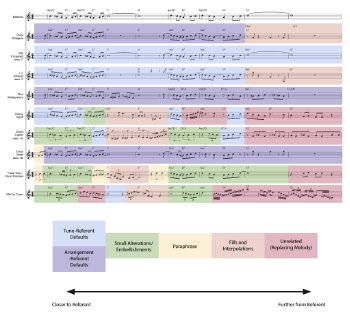

[5.8] Richard Rodgers and Lorenz Hart’s “Isn’t It Romantic?” was first introduced in the 1932 film Love Me Tonight and has since been recorded by a variety of both jazz and popular acts. Because many of the better known vocal renditions by singers such as Ella Fitzgerald, Johnny Hartman, and Mel Tormé feature elaborate large-ensemble orchestration and relatively little improvisation, I will instead focus on an avant-texte of small-ensemble recordings that make use of fewer arranged parts and treat the harmonic structure of the tune more loosely (Example 16).(65) This more limited comparison will allow for closer attention to the ways in which structural levels compare between versions.

Example 17. Transcriptions of the foreground harmonies in the opening head in each of the recordings of the “Isn’t It Romantic?” avant-texte

(click to enlarge)

Example 18. Demonstration of the derivation of structural levels in the opening A section of Oscar Peterson’s recording of “Isn’t It Romantic?”

(click to enlarge)

[5.9] Example 17 compares my transcriptions of the harmonic foregrounds of the opening head of each recording.(66) In each transcription, harmonies were determined based on piano voicings and bass lines, and are meant to represent the harmonies a listener might deduce from the sounding recording, not the referents of the individual players. Example 18 shows how the foreground of the opening A section of Oscar Peterson’s recording may be derived from deeper structural levels.(67) (Structural levels for the opening head of each recording may be found in the Appendix.) At each level, harmonies that derive their meaning from others are reduced out as follows: applied chords dependent on their target chords are denoted by a curved, solid arrow; ii chords elaborating V in a ii–V schema are grouped together with a bracket; and tritone substitutes functioning like the dominant chords for which they stand in are denoted by a curved, dashed arrow. At deeper levels of structure, these chords are replaced by the harmonies from which they derive their meaning. The resulting middleground structures are not suitable for performance, nor do they themselves represent the harmonic content of a referent. Rather, referent defaults emerge at or near the foreground level and are underpinned by deeper levels of middleground structure. The harmonic aspect of an improviser’s referent is therefore multi-layered and involves coordinating movement between structural levels with the formal and metric time-spans to which they are tethered.

Example 19. Spectrum of relations between harmonic structural levels

(click to enlarge)

[5.10] Instead of relying on multiple layers to compare the harmonic content of postulated referents, we can adapt the spectrum from Example 4 to show how foreground harmonies are dependent upon those from deeper structural levels; this new harmonic spectrum of relations appears in Example 19. This spectrum enables us to more easily trace the derivation of harmonies from the middleground to the foreground. The spectra in Example 4 and Example 19 are similarly structured—in that the left side of each spectrum represents something more fundamental to the referent than the right side—and therefore offer comparable ways of thinking about how performances relate to a postulated referent. Despite this, it is important to emphasize that these relationships are not determined in the same way for melody and harmony. In contrast to the spectrum from Example 4, which is designed to show how melodic utterances relate to a postulated referent, the spectrum in Example 19 shows distance from a particular middleground harmony.(68) Each harmony at a given structural level is understood to be dependent upon a harmony at a lower structural level, meaning that red harmonies are dependent on those that are orange, orange harmonies depend on those that are yellow, yellow harmonies depend on those that are green, and green harmonies depend on those that are blue. Blue harmonies represent the lowest level of structure, in this case the middleground harmonies at the level of the measure. While it would be possible to use a still deeper structural level as the (blue) point of comparison, this middleground serves as a convenient comparison point because discrepancies at this level are relatively uncommon.

Example 20. A multilayered postulated harmonic referent based on the middleground levels of all five recordings in the “Isn’t It Romantic?” avant-texte

(click to enlarge)

[5.11] Using the most common features from these middlegrounds as a basis of comparison, we can create a provisional set of referent defaults common to these five recordings.(70) Example 20 shows this multilayered postulated referent and compares it against the foreground harmonies of each recording. The top row of Example 20 shows middleground harmonies at the level of the measure, while the fifth row shows the shared defaults at the foreground level. The tune most typically features a harmonic rhythm of two chords per measure, with only Betty Carter’s and Chet Baker’s renditions departing from this harmonic rhythm for more than a measure or two. A question mark (“?”) appears in the table where there is an expectation of a chord change due to the harmonic rhythm, but not for any particular harmony. In cases where there are two defaults but one is more common than the other, they are indicated in the table as first- and second-level defaults. Although there is significant variation between the foreground harmonies, the middleground defaults do not provide a sufficient alternative as they oversimplify the harmonic motion. In cases where there are two choices but neither is more common, they are marked in the table as unranked defaults. The middleground does, however, serve to coordinate the foreground defaults, ensuring that variations at the foreground are underpinned by shared departure and arrival harmonies.

[5.12] There are a few places where notable discrepancies from the shared middleground bubble up to the musical surface, revealing how seemingly small improvisational choices can have an impact on multiple measures. For example, the C section most often begins with an Fm chord, but the Oscar Peterson rendition begins instead with

[5.13] A few passages use established harmonic schemas. The A sections often (but not always) feature I–vi–ii–V schemas, and ii–Vs appear repeatedly at various structural levels in all versions. The C section features a descending stepwise line in the bass, sometimes referred to as a CESH (Chromatic Embellishment of Static Harmony) schema in mm. 27–28, corresponding with the climax of the melody, that is realized in varying ways.(72) CESH schemas typically elaborate a single harmony through a descending or ascending voice-leading line. When this voice-leading line appears in or is moved to the bass voice, improvisers will sometimes harmonize each bass note of the resulting walkdown. Four of the five recordings feature the bass line C–

Example 21. A comparison of the postulated harmonic referent of the “Isn’t It Romantic?” avant-texte and the lead sheets from the fifth and sixth editions of The Real Book, Vol. 1

(click to enlarge)

[5.14] Although “Isn’t It Romantic?” appears in both the fifth and sixth editions of The Real Book, Vol. 1, the harmonies found in the lead sheets in each of these fakebooks differ from those in our avant-texte (Example 21).(73) Although these lead sheets mostly rely on the same middleground structure as the recordings, they also feature idiosyncrasies that are not especially common. For example, both feature a passing diminished chord in the second half of m. 3, which does not match the unranked referent defaults (although as discussed above it commonly substitutes for the second chord of a I–vi–ii–V schema). More striking is the prominent use of

[5.15] The postulated referent in Example 20—and the method used to arrive at it—has many advantages. First, it requires careful comparison between different versions of the tune. This ensures that we are aware of which chord changes in a given version may be unusual in relation to other versions. Second, examining multiple layers of harmony allows us to identify the larger-scale ramifications of surface-level harmonic idiosyncrasies in the tune. And finally, unlike when using fakebook lead sheets, the postulated referent responds to the specific melodies and harmonies of the versions in our avant-texte. Through furnishing the postulated referent in Example 20 and comparing it to recordings in the avant-texte, we get a glimpse into how different versions of “Isn’t It Romantic?” interact with the potential expectations of improvisers and listeners. Harmonic transformations, like those discussed above in the Oscar Peterson, Bill Evans, and Chet Baker recordings, are easily identifiable through this process of comparison. The postulated referent therefore ensures that there is an appropriate, carefully worked-out point of comparison for further analysis.

6. Coda: The Textility of Jazz Tunes

[6.1] Tunes are central to the jazz tradition, in that they remain the most common basis for jazz performances, and learning a wide variety of tunes is considered an important part of many jazz musicians’ training. Yet tunes are not synonymous with musical works. The role played by tunes in the ontology of jazz is fundamentally different from that played by the work concept in the Western art tradition. Jazz improvisations are not usually conceived of as realizations of tunes, nor are tunes generally considered as the locus of critical attention in a jazz performance. Instead, they simply serve as one part, albeit an important part, of an improvised performance. Most listeners are not as interested in the tune as they are with what improvisers do with the tune.

[6.2] In their article on the role of notation and annotation in the performance of music, Emily Payne and Floris Schuiling (2017) seek to rein in the methodological ramifications of the performative turn insomuch as it has made scholars disregard the specificity offered by notation. Proposing Timothy Ingold’s (2010) notion of textility as a way forward, this pair of authors highlight Ingold’s metaphor of the weaver:

the weaver does not shape threads into a pre-established form, but lets this form emerge by binding together separate threads. That is to say, even with a pre-established design, the process of making is not so much a matter of “moulding” the material into shape, but of negotiating the motion and the tension of the threads, the various elements of the loom, and the particular characteristics of the fabric. What Ingold calls the “textility” of creative practice is meant to shift attention to the materials used in creative work, and the “tactile and sensuous knowledge of line and surface” that comes with handling them. (Payne and Schuiling 2017, 441)

Jazz musicians playing tunes are likewise weavers: they do not shape musical utterances to fit a particular musical-structural model but allow the sounding music to emerge from an ongoing negotiation with the fabrics of the tune and the utterances of other improvisers.(75) As listeners, we are left with the resulting form and a suggestion of the processes that led to its shape. Those processes can often seem opaque, but tracing them is an important and necessary goal if we are to understand the role musical structure plays in improvised musical traditions.

Sean R. Smither

The Juilliard School

60 Lincoln Center Plaza, New York, NY 10023

ssmither@juilliard.edu

Mannes School of Music, The New School

55 W 13th St, New York, NY 10011

smits279@newschool.edu

Works Cited

Baker, Benjamin. 2021. “Standard Practices: Intertextuality, Agency, and Improvisation in Jazz Performances of Modern Popular Music.” PhD diss., University of Rochester, Eastman School of Music.

Beach, David. 1995. “Phrase Expansion: Three Analytical Studies.” Music Analysis 14 (1): 27–47. https://doi.org/10.2307/853961.

Bellemin-Noël, Jean. 1972. Le texte et l’avant-texte: Les brouillons d’un poème de Milosz. Libr. Larousse.

Berkowitz, Aaron. 2010. The Improvising Mind: Cognition and Creativity in the Musical Moment. Oxford University Press.

Berliner, Paul. 1994. Thinking in Jazz: The Infinite Art of Improvisation. University of Chicago Press. https://doi.org/10.7208/chicago/9780226044521.001.0001.

Biamonte, Nicole. 2008. “Augmented Sixth Chords vs. Tritone Substitutes.” Music Theory Online 14 (2). https://doi.org/10.30535/mto.14.2.2.

Born, Georgina. 2005. “On Musical Mediation: Ontology, Technology, and Creativity.” Twentieth-Century Music 2 (1): 7–36. https://doi.org/10.1017/S147857220500023X.

Bowen, José A. 1993. “The History of Remembered Innovation: Tradition and its Role in the Relationship between Musical Works and their Performances.” The Journal of Musicology 11 (2): 139–73. https://doi.org/10.2307/764028.

—————. 2015. “Who Plays the Tune in ‘Body and Soul’? A Performance History Using Recorded Sources.” Journal of the Society for American Music 9 (3): 259–92. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1752196315000176.

Boyle, Antares. 2021. “Flexible Ostinati, Groove, and Formal Process in Craig Taborn’s Avenging Angel.” Music Theory Online 27 (2). https://doi.org/10.30535/mto.27.2.6.

Broze, Yuri, and Daniel Shanahan. 2013. “Diachronic Changes in Jazz Harmony: A Cognitive Perspective.” Music Perception 31 (1): 32–45. https://doi.org/10.1525/mp.2013.31.1.32.

Caplin, William. 1998. Classical Form: A Theory of Formal Functions for the Instrumental Music of Mozart, Haydn, and Beethoven. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780195104806.001.0001.

Coker, Jerry, Bob Knapp, and Larry Vincent. 1997. Hearin’ the Changes: Dealing with Unknown Tunes by Ear. Alfred Music.

Cook, Nicholas. 2001. “Between Process and Product: Music and/as Performance.” Music Theory Online 7 (2). https://doi.org/10.30535/mto.7.2.1.

Davies, Stephen. 2001. Musical Works and Performances: A Philosophical Exploration. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/0199241589.001.0001.

Davis, Whitney. 1996. Replications: Archaeology, Art History, Psychoanalysis. Penn State University Press.

Deppman, Jed, Daniel Ferrer, and Michael Groden. 2004. Genetic Criticism: Texts and Avant-textes. University of Pennsylvania Press.

De Souza, Jonathan. 2022. “Melodic Transformation in George Garzone’s Triadic Chromatic Approach; or, Jazz, Math, and Basket Weaving.” Music Theory Spectrum 44 (2): 213–30. https://doi.org/10.1093/mts/mtac003.

Ellis, Carolyn. 2004. The Ethnographic I: A Methodological Novel about Autoethnography. AltaMira Press.

Ellis, Carolyn, Tony E. Adams, and Arthur P. Bochner. 2011. “Autoethnography: An Overview.” Historical Social Research 36 (4): 273–90.

Floyd, Jr., Samuel A. 1991. “Ring Shout! Literary Studies, Historical Studies, and Black Music Inquiry.” Black Music Research Journal 11 (2): 265–87. https://doi.org/10.2307/779269.

Gates, Jr., Henry Louis. 1988. The Signifying Monkey: A Theory of Afro-American Literary Criticism. Oxford University Press.

Geyer, Benjamin. 2019. “Maria Schneider’s Forms: Norms and Deviations in a Contemporary Jazz Corpus.” Journal of Music Theory 63 (1): 35–70. https://doi.org/10.1215/00222909-7320462.

—————. 2021. Music Theory in Mind and Culture. Self-published. https://www.bengeyer.com/teacher.

Giddins, Gary, and Scott DeVeaux. 2009. Jazz. W. W. Norton.

Givan, Benjamin. 2002. “Django Reinhardt’s ‘I’ll See You in My Dreams.’” Annual Review of Jazz Studies 12: 41–62.

—————. 2016. “Rethinking Interaction in Jazz Improvisation.” Music Theory Online 22 (3). https://doi.org/10.30535/mto.22.3.7.

Goldman, Andrew. 2016. “Improvisation as a Way of Knowing.” Music Theory Online 22 (4). https://doi.org/10.30535/mto.22.4.2.

Hannaford, Marc. 2019. “One Line, Many Views: Perspectives on Music Theory, Composition, and Improvisation through the Work of Muhal Richard Abrams.” PhD diss., Columbia University.

Hatten, Robert. 1997. “Markedness and a Theory of Musical Expressive Meaning. Contemporary Music Review 16 (4): 51–63. https://doi.org/10.1080/07494469700640231.

Helm, Ethan. 2022. “Analyzing Jazz Improvisation with Voice-Leading Models: A Study of Saxophonists’ Harmonic Variations on Rhythm Changes.” PhD diss., New York University.

Hepokoski, James, and Warren Darcy. 2006. Elements of Sonata Theory: Norms, Types, and Deformations in the Late-Eighteenth-Century Sonata. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195146400.001.0001.

Hodson, Robert. 2007. Interaction, Improvisation, and Interplay in Jazz. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203944103.

Ingold, Tim. 2010. “The Textility of Making.” Cambridge Journal of Economics 34 (1): 91–102. https://doi.org/10.1093/cje/bep042.

Johnson-Laird, Philip N. 2002. “How Jazz Musicians Improvise.” Music Perception 19 (3): 415–42. https://doi.org/10.1525/mp.2002.19.3.415.

Kane, Brian. 2017. “Jazz, Mediation, Ontology.” Contemporary Music Review 37 (5–6): 507–28. https://doi.org/10.1080/07494467.2017.1402466.

—————. 2024. Hearing Double: Jazz, Ontology, Auditory Culture. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780190600501.001.0001.

Kernfeld, Barry. 2006. The Story of Fakebooks: Bootlegging Songs to Musicians. Scarecrow Press.

Larson, Steve. 1999. “Swing and Motive in Three Performances by Oscar Peterson.” Journal of Music Theory 43 (2): 283–314. https://doi.org/10.2307/3090663.

—————. 2002. “Musical Forces, Melodic Expectation, and Jazz Melody.” Music Perception 19 (3): 351–85. https://doi.org/10.1525/mp.2002.19.3.351.

—————. 2009. Analyzing Jazz: A Schenkerian Approach. Pendragon Press.

Lerdahl, Fred, and Ray Jackendoff. 1983. A Generative Theory of Tonal Music. The MIT Press.

Levine, Mark. 1995. The Jazz Theory Book. Sher Music.

Lewis, Eric. 2019. Intents and Purposes: Philosophy and the Aesthetics of Improvisation. University of Michigan Press. https://doi.org/10.3998/mpub.10075702.

Lewis, George E. 1996. “Improvised Music after 1950: Afrological and Eurological Perspectives.” Black Music Research Journal 16 (1): 91–122. https://doi.org/10.2307/779379.

Love, Stefan Caris. 2012. “An Approach to Phrase Rhythm in Jazz.” Journal of Jazz Studies 8 (1): 4–32. https://doi.org/10.14713/jjs.v8i1.35.

—————. 2016. “The Jazz Solo as Virtuous Act.” The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism 74 (1): 61–74. https://doi.org/10.1111/jaac.12238.

—————. 2017. “An Ecological Description of Jazz Improvisation.” Psychomusicology: Music, Mind, and Brain 27 (1): 31–44. https://doi.org/10.1037/pmu0000173.

Martin, Henry. 1988. “Jazz Harmony: A Syntactic Background.” Annual Review of Jazz Studies 4: 9–30.

—————. 1996. Charlie Parker and Thematic Improvisation. Scarecrow Press.

—————. 2012. “Charlie Parker and ‘Honeysuckle Rose’: Voice Leading, Formula, and Motive.” Music Theory Online 18 (3). https://doi.org/10.30535/mto.18.3.6.

—————. 2018a. “Prolongation and Its Limits: The Compositions of Wayne Shorter.” Music Theory Spectrum 40 (1): 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1093/mts/mty006.

—————. 2018b. “Four Studies of Charlie Parker’s Compositional Processes.” Music Theory Online 24 (2). https://doi.org/10.30535/mto.24.2.3.